Millie Cutting: physician’s wife makes her own mark

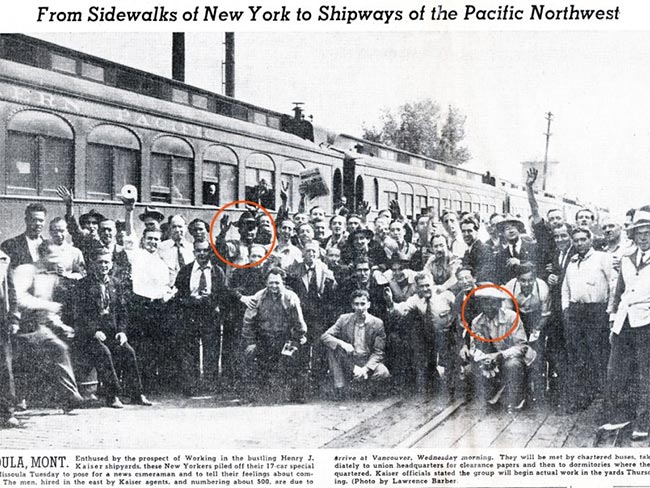

From coordinating community groups to the World War II home front, Millie Cutting's resilience overcame the health plan’s early challenges.

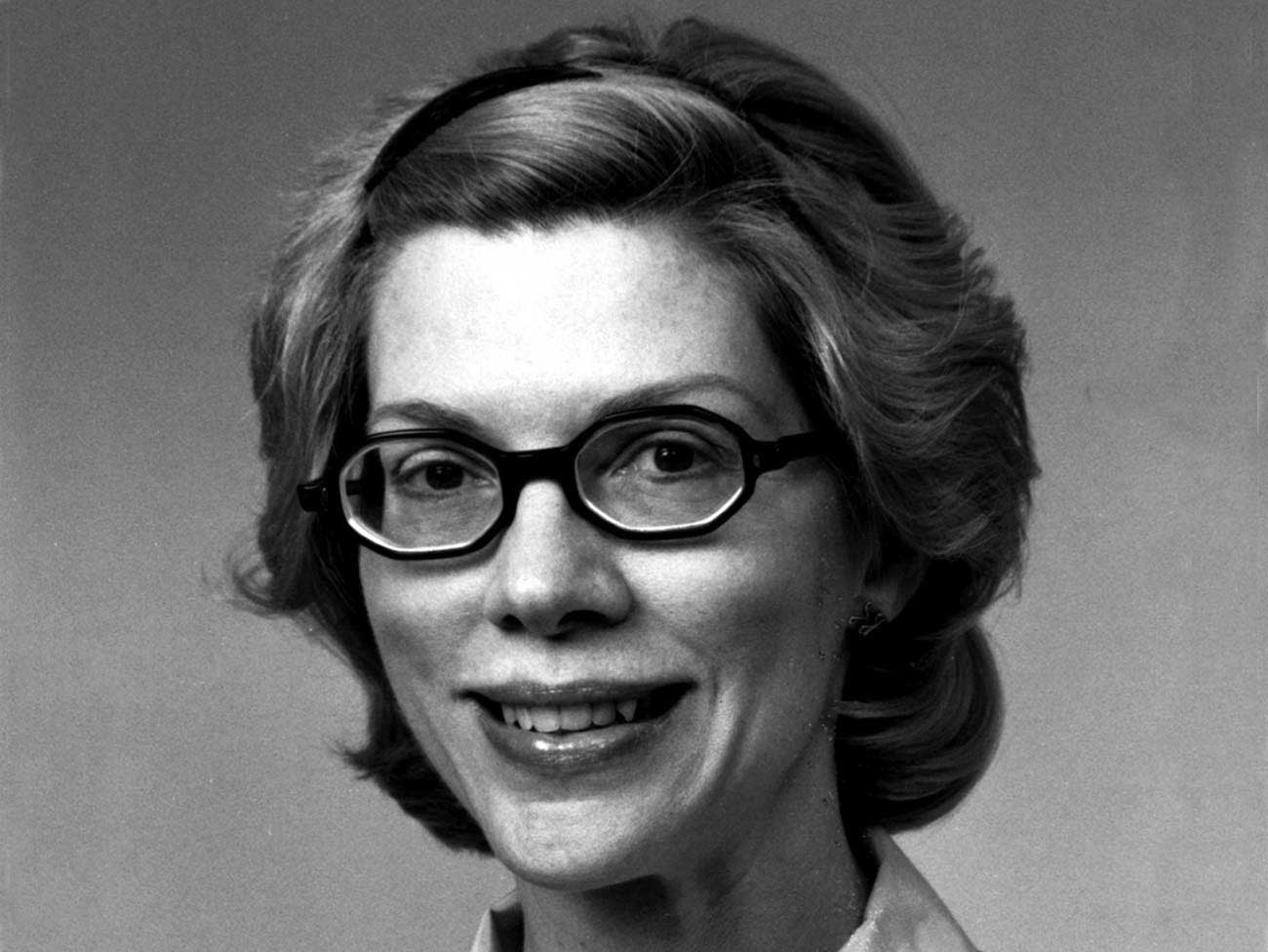

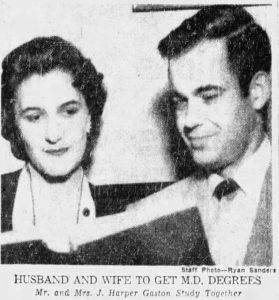

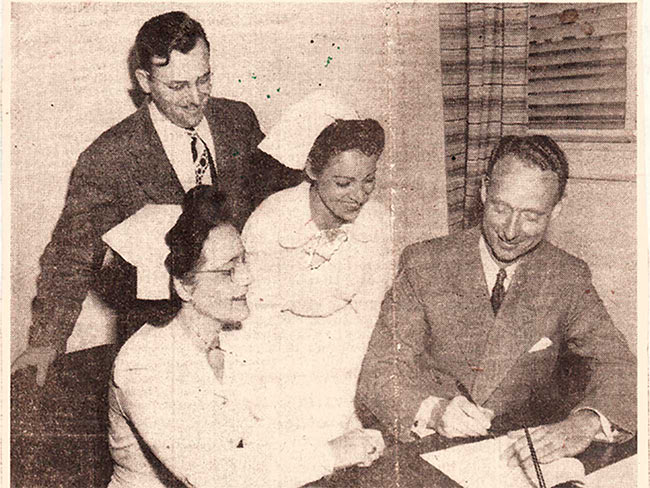

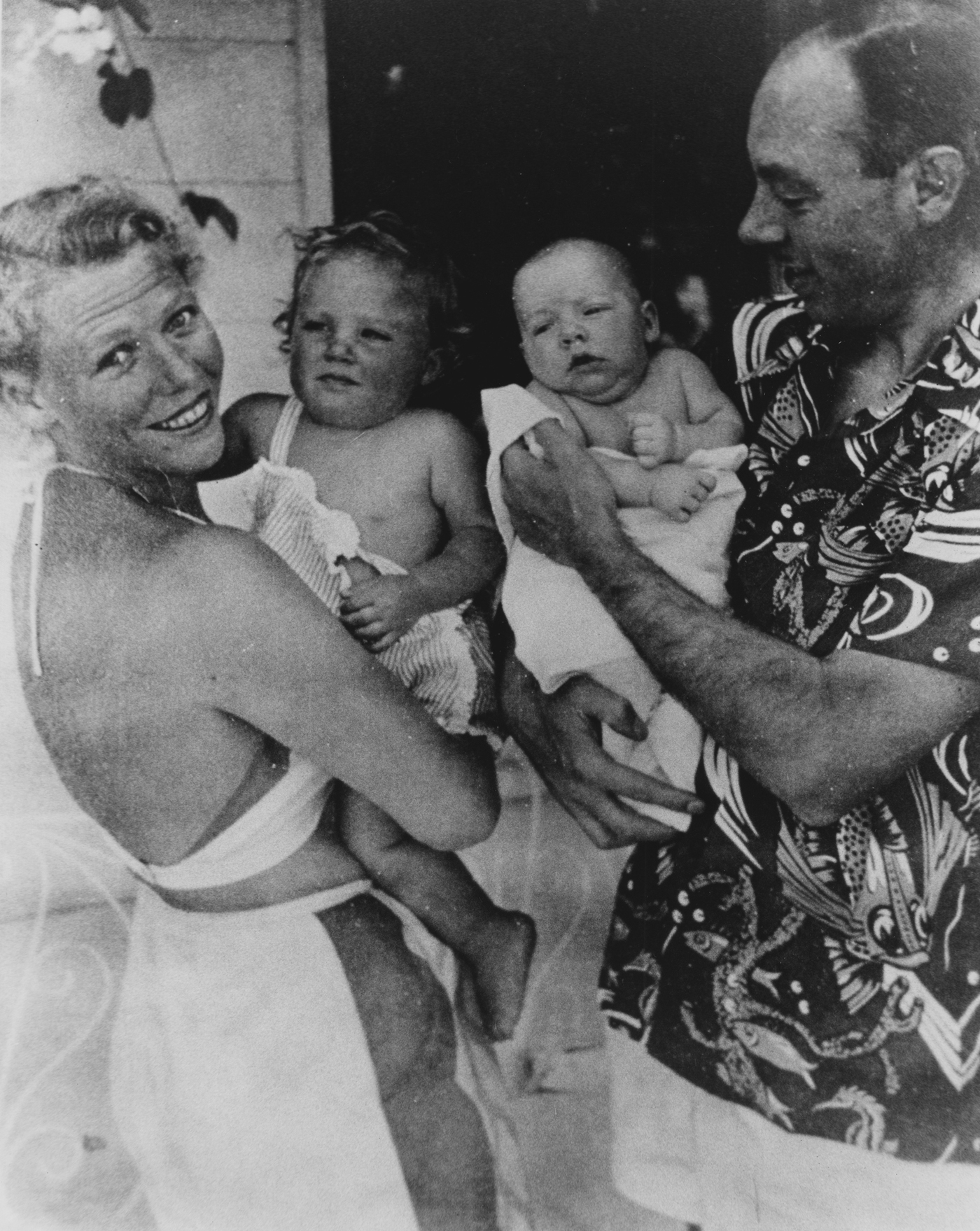

Millie Cutting in the early years of Permanente Medicine.

Millie Cutting was the wife of Kaiser Permanente’s pioneering chief surgeon Cecil Cutting, but her influence on the fledgling medical program during World War II contradicts any cliché prescribing the role of a doctor’s spouse. She was a vibrant, energetic force in her own right, a good woman behind a good man, but much, much more.

The Cuttings met in Northern California at Stanford University in the early 1930s. He was training to become a physician; she was a registered nurse with a degree from Stanford. They met on the tennis courts and married in 1935.

During her husband’s nonpaid internship, Millie Cutting worked two jobs — for a pediatrician during the day and an ophthalmologist in the evenings — to pay the bills. He was making $300 a month as a resident when Sidney Garfield, MD, contacted him about joining the medical care program for Henry Kaiser’s workers on the Grand Coulee Dam in Washington State.

Millie was at first reluctant to leave San Francisco to relocate in the desert. But when Cecil convinced her that he would have more opportunity as a surgeon with Garfield than in San Francisco, she was game. “Oh, she was willing to go along; she had a lot of spirit and enthusiasm,” Cecil Cutting said in his oral history.

“I think with a little reluctance, perhaps of the unknown,” he told interviewer Malca Chall of UC Berkeley's Regional Oral History Office in 1985. "We didn’t have any money. She had worked during my residency as a nurse, to keep us in food.” Sidney Garfield was able to match the $300 Cutting was earning at Stanford to get him to Coulee.

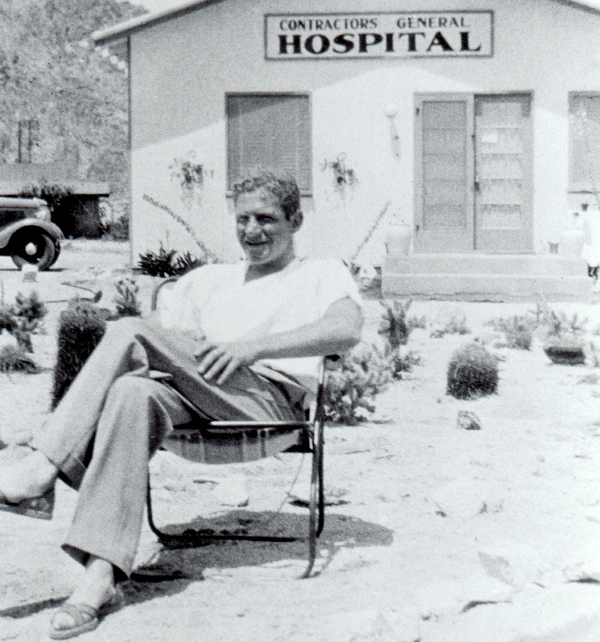

A rough start at Grand Coulee

Unfortunately for Millie, things at Coulee didn’t start out too well. John Smillie, MD, writes: “Cecil and Millie Cutting resided in the company hotel. They were flat broke. The young couple had exhausted their resources getting to Washington. Neither of them thought of asking for an advance.” 1

“My wife couldn’t take the heat very well,” Cutting told Smillie. “She would lay on the bed with a wet sheet over her; and we didn’t have enough money to eat, really. She would go to the cafeteria and see how far she could stretch a few pennies to eat. Of course, I ate well at the hospital and had air conditioning and everything.

“She finally learned to come over and sit in the waiting room on the very hottest days. Since then, Dr. Garfield laughed at us and said, ‘Why didn’t you ask me for money?’ We didn’t know enough to do that!”

“At the end of the first discomforting month, Cutting received his first paycheck for $350,” Smillie writes. “He and Millie moved into a remodeled schoolhouse, the largest home in the community, and it soon became the social center for the physicians and the Kaiser executives.”

Millie gets her groove back

During the rest of their time at Coulee, Millie not only got her energy back but she exhibited her strength as a staff nurse and as a community volunteer. Probably her most significant contribution was the development of a well-baby clinic in a community church. As a volunteer, she organized the clinic and went door to door soliciting funds for its operation. She had no qualms about knocking on the portals of the town’s brothels.

“The madams were very friendly,” Cecil Cutting told Smillie. “The community church provided the space, and the houses of ill repute the money – a very compatible community.”

Garfield’s right-hand ‘man’ at wartime shipyards

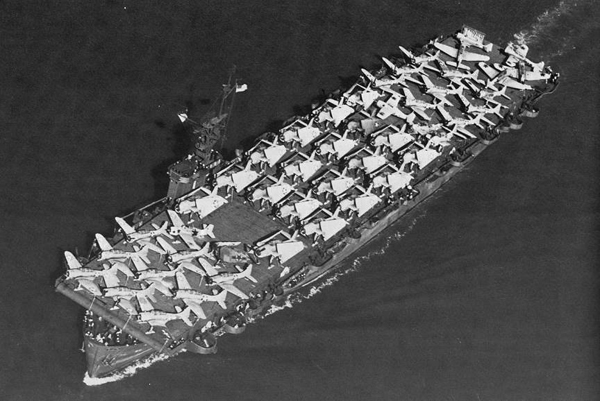

The Grand Coulee Dam was completed in 1940, and the medical staff and their families scattered. The Cuttings settled briefly in Seattle where Dr. Cutting set up a surgery practice. But it wasn’t very long before World War II broke out and Dr. Garfield was called upon again to assemble the medical troops.

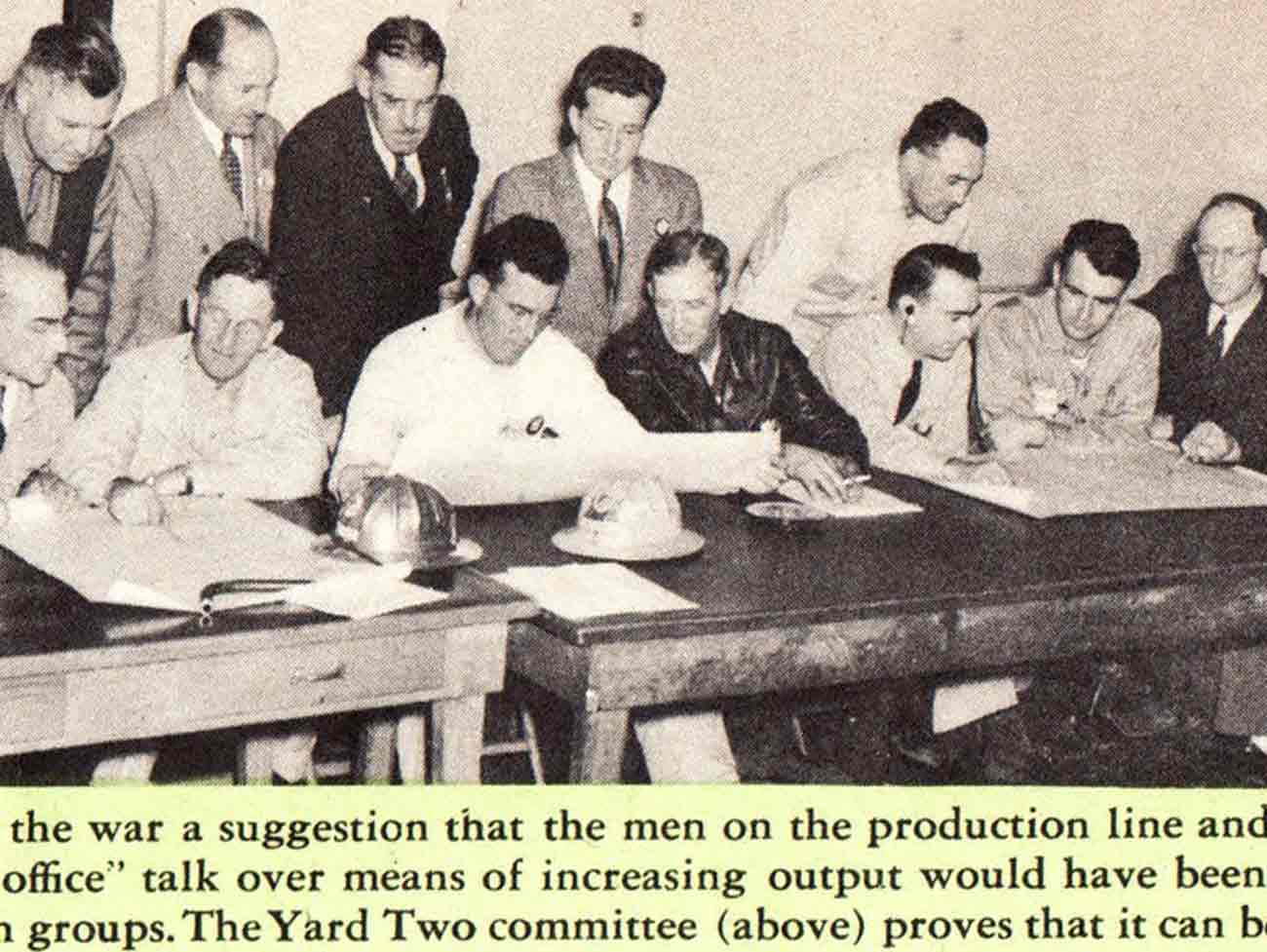

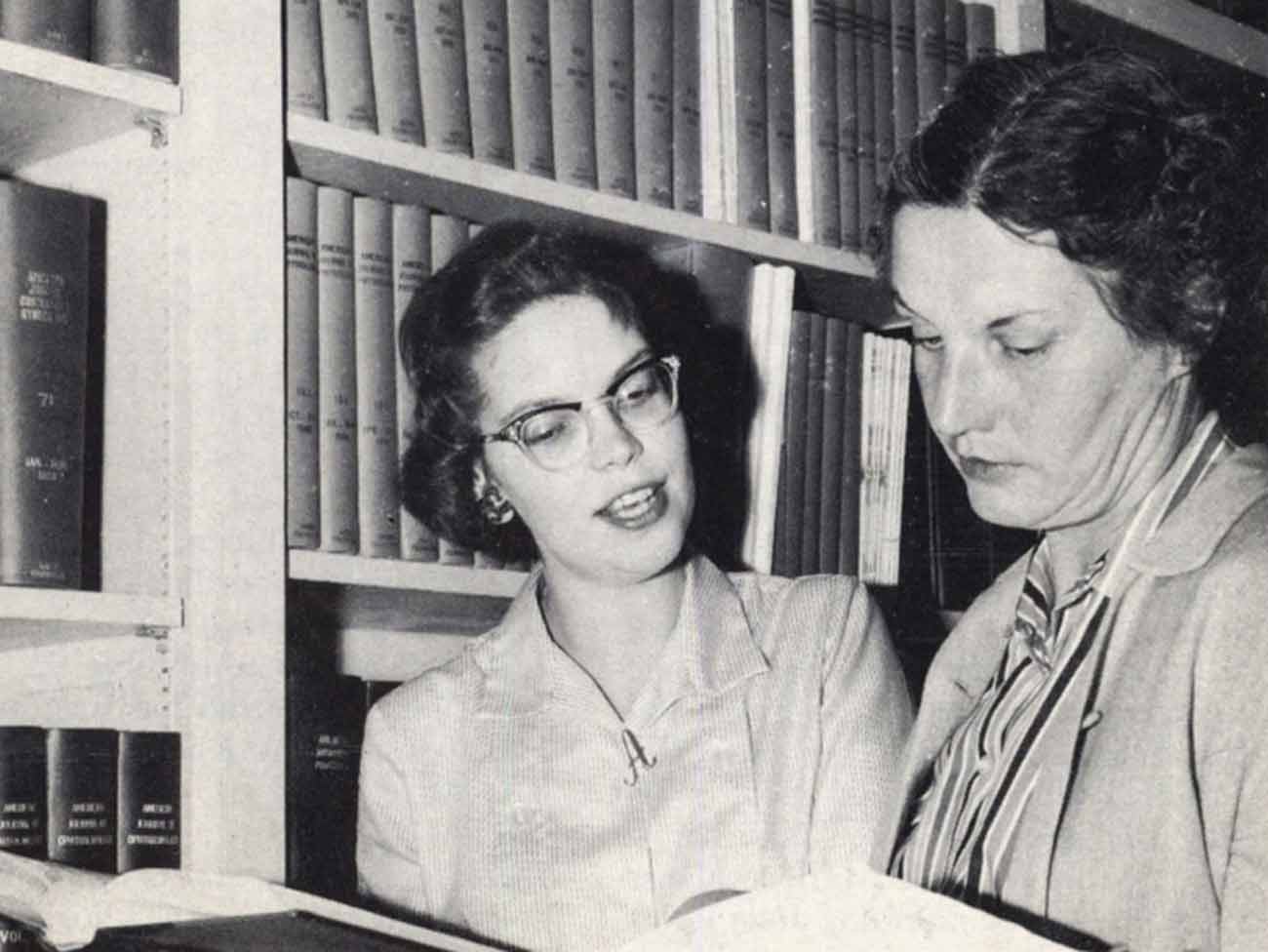

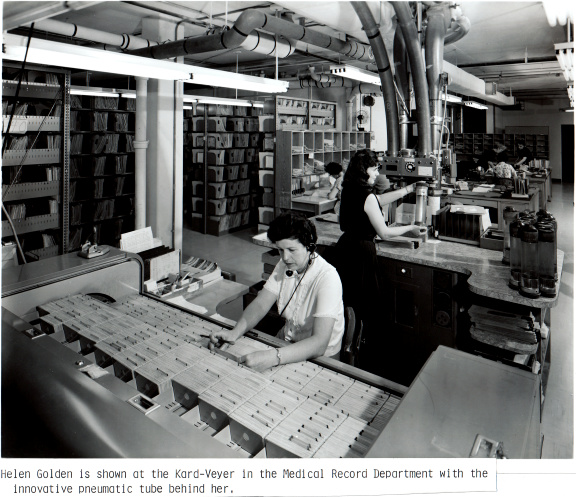

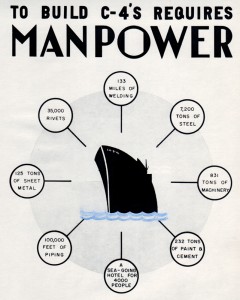

Cecil Cutting was the first physician to arrive in Richmond, California, where Henry Kaiser set up 4 wartime shipyards. Millie Cutting volunteered to work side by side with Sidney Garfield to get the medical care program up and running and to take charge of any job that needed to be done.

She recruited, interviewed and hired nurses, receptionists, clerks, and even an occasional doctor, to staff the health care program that was set up in a hurry in 1942. She smoothed the way for newcomers and helped them find homes in the impossible wartime housing market.

Thoroughly adaptable Millie drove a supply truck between the Oakland and Richmond hospitals and the first aid stations and served as the purchasing agent for a time. As she had done at Grand Coulee, Millie set up a well-baby clinic for shipyard workers’ families, and she opened her home in Oakland as a social center for the medical care staff.

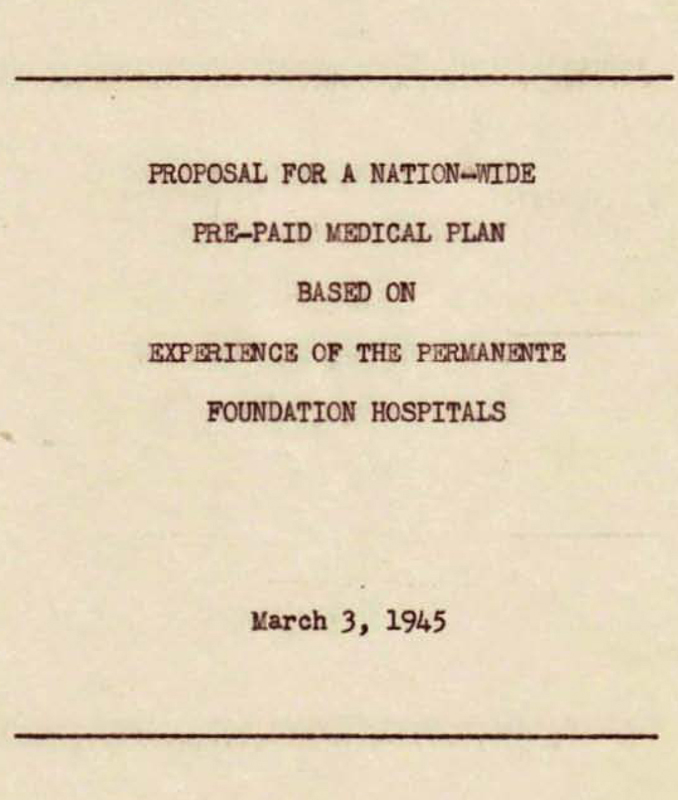

Perturbing postwar perceptions

After the war, Millie and Bobbie Collen, wife of Morris Collen, MD, started a Permanente wives group in 1949. The association created a support system against an often hostile medical establishment that shunned prepaid group practice of medicine as “socialist.” The physicians were not allowed in the local medical society, and the women felt socially ostracized.

“They organized themselves as the Permanente Wives Association, which had a nickname, 'Garfield’s Girls,' " Smillie wrote. “They had dances, parties, picnics and social outings several times a year that were really a lot of fun. The auxiliary. . .became famous for its rummage sales.”

The Cuttings became good friends with Sidney Garfield, and in fact, he spent periods of time living with them in their Orinda home in the 1940s and 1950s. Cecil Cutting credits Garfield with the couple’s decision in 1948 to adopt their two children, Sydney and Christopher. “He talked us into it,” Cutting said.

Garfield often went to them for advice about business matters, as well. “I think he talked over a lot of things with Dr. Cutting and Millie,” said Smillie in his oral history. “He had a great deal of confidence in their judgment. If they told him he was wrong, he was able to accept it.”

The Cuttings were the friends Garfield chose to share the happy moment of burning the mortgage papers once the renovated Fabiola Hospital (the first Kaiser Foundation Hospital in Oakland) note was paid off. The private celebration took place in the Cuttings’ home with just Garfield, Millie, and Cecil present.

Dr. Cutting worked his way up to become the executive director of The Permanente Medical Group in 1957 and retired in 1976 after 35 years as a major figure in the organization. Millie Cutting continued to volunteer at the Oakland Kaiser Foundation Hospital all of her life. She had to quit in 1985 when she became too ill to leave her house. She died that year at the age of 73. Cecil Cutting received a flood of condolence notes from all the people whose lives Millie had touched.

One woman wrote: “When life seemed just too much, Millie’s unforgettable laughter would ring in my mind’s ear, and the will to tackle life again would be there like a gift from her. She didn’t just give. She was a gift.”

1 John Smillie, MD, Can Physicians Manage the Quality and Costs of Health Care? The Story of The Permanente Medical Group, McGraw-Hill Companies, New York, 1991