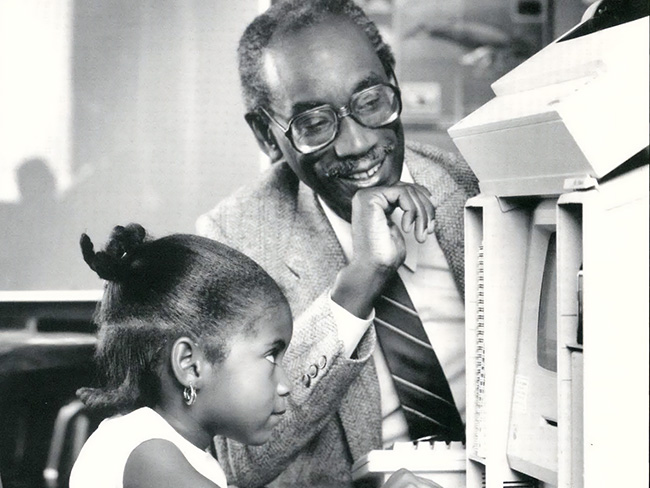

Eugene Hickman, MD — Pioneering Black physician

Dr. Hickman had a long career at Kaiser Permanente, becoming president of the hospital staff and later chief of radiology.

Dr. Hickman conducting a training session at Kaiser Permanente Oakland Medical Center, circa 1970. Photo courtesy of John Hickman.

Health care practitioners of color have always struggled for recognition and respect. And in the medical landscape following World War II, segregated facilities and conservative professional associations meant that few Black doctors were on the staff of major hospitals. But the arc of social justice moved a little in 1959, when Eugene Hickman, MD, became the first Black physician to become part of the Permanente Foundation Health Plan in Northern California.

Even though Henry J. Kaiser steadfastly fought against segregation in his WWII shipyards and its health care program, breaking the racial barrier in physicians lagged. We know that at least one Black physician was on contract at the Oakland hospital as early as 1945, but it wasn’t until 1954 when the racially diverse International Longshore and Warehouse Union complained about the absence of Black physicians in Southern California that radiologist Raleigh C. Bledsoe, MD, was brought into the Permanente Medical Group. Five years later, Dr. Hickman started his career up north.

From left to right: Dr. Hickman; Dr. Irving Lomhoff and his wife; and Eunice Hickman in Lake Tahoe, circa 1960. Photo courtesy of John Hickman.

Eugene A. Hickman was born in 1921 in Alton, Illinois. He served as a trumpeter in the U.S. Navy Band stationed at Hampton Institute in Virginia, and graduated from Nashville’s Meharry Medical College (the second-oldest medical school for African Americans in the nation) in 1949, specializing in radiology. Looking for opportunity, he moved west to California. There he practiced in Los Angeles, first briefly in a traditional partnership, then with the Los Angeles City Health Department, Mt. Sinai Clinic (now Cedars-Sinai Medical Center), and the Veterans Administration hospital.

Dr. Hickman wrote an unpublished memoir of his life that describes his experience of choosing to move to Northern California and work for the Kaiser Permanente Hospital in Oakland:

"I was hired by Dr. James Davis at the Veterans’ Hospital on Sawtelle, near UCLA. I became the chief of Radiology at the branch for the mentally impaired. This hospital had an excellent staff. Again I was treated with cordiality and respect. Seldom was the work really interesting, so I spent a lot of time reading.

"It occurred to me that I would lose the skills I had acquired and that this would be a dead end. My wife, Eunice, encouraged me to move on and asked me if I didn’t think I was worth more than I was being paid. I had a major problem. Hospital radiology departments were, and still are, staffed by a group of radiologists, invariably white. It would not have been a good decision, from a financial point of view, for them to hire me.

"I found a copy of the annual Journal of the American Medical Association in which was listed medical facilities throughout the U.S. and names of persons to contact when searching for employment. So again I wrote a few letters.

"One was to Dr. Irving Lomhoff, who was then the chief radiologist at Kaiser Hospital, Oakland, Calif. I had seen a Life magazine article about the showcase Kaiser Hospital, Walnut Creek, Calif. Otherwise I knew absolutely nothing about the Kaiser Permanente system. Dr. Lomhoff responded to my inquiry and suggested I come to Oakland for an interview. I was still living in Los Angeles. I had received so many rejections, I found it difficult to take Lomhoff’s invitation seriously. Eunice very strongly suggested I forget the past and go for it. I needed that push.

“I arrived [by train] in Oakland on a Monday morning, midsummer 1959 at about 8 a.m … [and] called Dr. Lomhoff. Of course, he told me to take a bus up Broadway and get off at MacArthur. I did just that, then started walking because I didn’t see anything resembling the hospital I had envisioned. I entered the MacArthur-Broadway building and called Lomhoff again. He told me he was a big stout red-haired Jew and would stand on the front porch to greet me on my arrival.

“Well, he was across the street and came out and stood on the porch of a building that I had not recognized as a hospital. In fact, I believe if I had seen a picture of this hospital beforehand, I probably would not have made the trip. Lomhoff greeted me very cordially and took me for coffee and pastry. Then we went to his office for a fairly long interview.

“At that time there was not, nor had there been, a Black physician on the hospital staff, but this was not to be a factor in the interview or its outcome. He gave me a tour of the facility and introduced me to many of the staff members. He warned me that I would probably encounter difficulty finding a place to live. How correct he was ...”

Dr. Hickman’s reception by fellow Kaiser Permanente physicians was not without struggle. He described experiencing hostility and condescension from some doctors, and even ugly rumors that members might leave the plan due to his hiring. But Dr. Lomhoff stood by him and things settled down. Dr. Hickman had a long career at Kaiser Permanente, becoming president of the hospital staff and later chief of the department of radiology. He ended his 30-year tenure in 1989.

Dr. Hickman also experienced discrimination of a different type, one entirely unrelated to his skin color:

"Before I started working at Kaiser Permanente, I didn’t know anything about the organization, nor about the attitude of the local medical society vis-a-vis Kaiser, but I soon found out. I had been a member of the LA County Medical Association for several years. I wanted to transfer my membership to the Alameda-Contra Costa Medical Association. I was informed that I would have to be interviewed by one or several members of the ACCMA. At the interview at an office on “Pill Hill” I was strongly advised against affiliating with Kaiser. I was assured Kaiser Permanente was a front for socialized medicine, if not in fact a communist cabal. ACCMA was not accepting physicians allied with the Kaiser organization. I was not enlightened as to the basis for this charge.

"Because of the history of racial discrimination/segregation in this country there were also medical associations for Black doctors, the one in Oakland named Sinkler Miller in honor of 2 outstanding Black physicians. [The Sinkler Miller Medical Association was formed in 1969 by physicians located in Alameda and Contra Costa Counties.] This group accepted me for membership but insisted on characterizing me as some sort of traitor to the Black physician community. I didn’t let that be a problem for me.

"Years later, ACCMA changed its policy and in fact had a member of Kaiser Permanente as president. There were members of ACCMA who were not in accord with the Association policy regarding Kaiser and with whom we had good relationships, educationally and socially."

Dr. Hickman passed away in 2013 after a short illness, survived by his wife of 64 years and 2 sons. We honor his courage and persistence in helping Kaiser Permanente provide high-quality, affordable health care services and to improve the health of our members and the communities we serve.

Thanks to those who helped with this story, including retired Kaiser Permanente physicians who remembered Dr. Hickman. A special thanks to Dr. Hickman’s son John, for generously sharing his father’s legacy.