Hannah Peters, MD, provides essential care to ‘Rosies’

When thousands of women industrial workers, often called “Rosies,” joined the Kaiser shipyards, they received care that helped them adjust to their new jobs.

Eastine Cowner removing coatings and corrosion from Liberty ship SS George Washington Carver at the Kaiser Richmond shipyard in 1943.

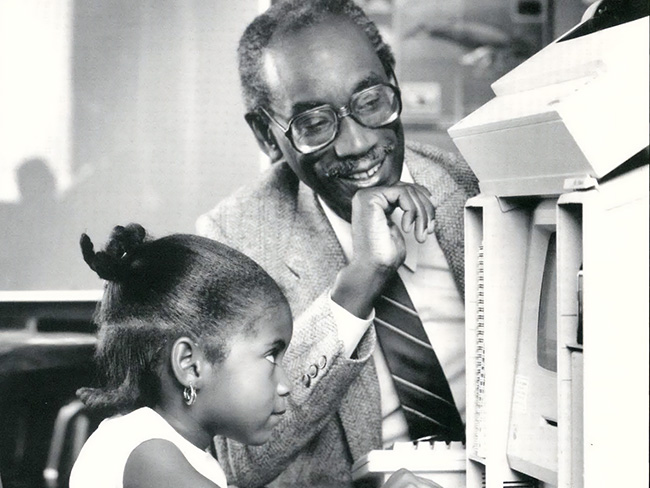

Millions of women joined the home front during World War II — answering the call to support the war effort by entering the industrial workforce. These women were often referred to as “Rosies” after the iconic image of “Rosie the Riveter.” At the Kaiser shipyards, the addition of so many women meant a big shift in who was receiving worksite medical care.

That new focus on the unique health needs of the female workforce established a standard of women’s health care that Kaiser Permanente continues today. And the reason thousands of Kaiser shipyard women workers returned home after the war in better health than when they arrived is in large part thanks to Hannah Peters, MD.

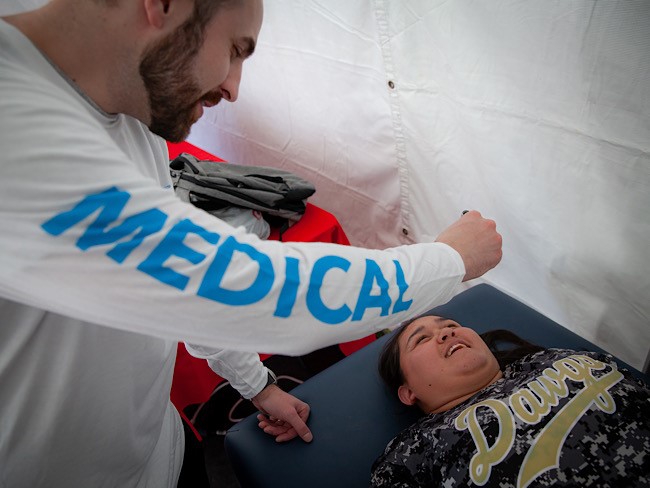

Providing care to women

Dr. Peters was a German-born physician trained in New York. She moved to California in 1940 and opened a private practice in East Oakland. Her business didn’t take off like she thought it would.

Then, she learned about the needs of the women working at the Kaiser Richmond shipyards. In 1941, she joined the shipyards’ medical care team established by Sidney R. Garfield, MD. Dr. Garfield would later co-found Kaiser Permanente with industrialist Henry J. Kaiser.

In her memoir, Dr. Peters remembered the situation at the shipyards.

“I joined the medical department, but it soon became clear to me that a gynecological department was necessary to take care of the special problems of the 23,000 women working in the yards,” wrote Dr. Peters. “A trained gynecologist was added to the staff, and we established special programs to deal with the question of abnormal menstruation, pregnancy, venereal disease, sexual problems, and to provide contraceptive services.”

The women at the shipyards faced unique health issues. For example, some of the women complained about excessive menstrual bleeding after starting their shipyard jobs. Dr. Peters figured out that it was caused by a vitamin B deficiency that she was able to treat.

Dr. Peters’ additional discoveries led her to co-author the article “Gynecology in Industry” with Wilson Footer, MD. It was published in the July 1945 issue of the Permanente Foundation Medical Bulletin, a scientific research journal.

Public health education at the shipyards

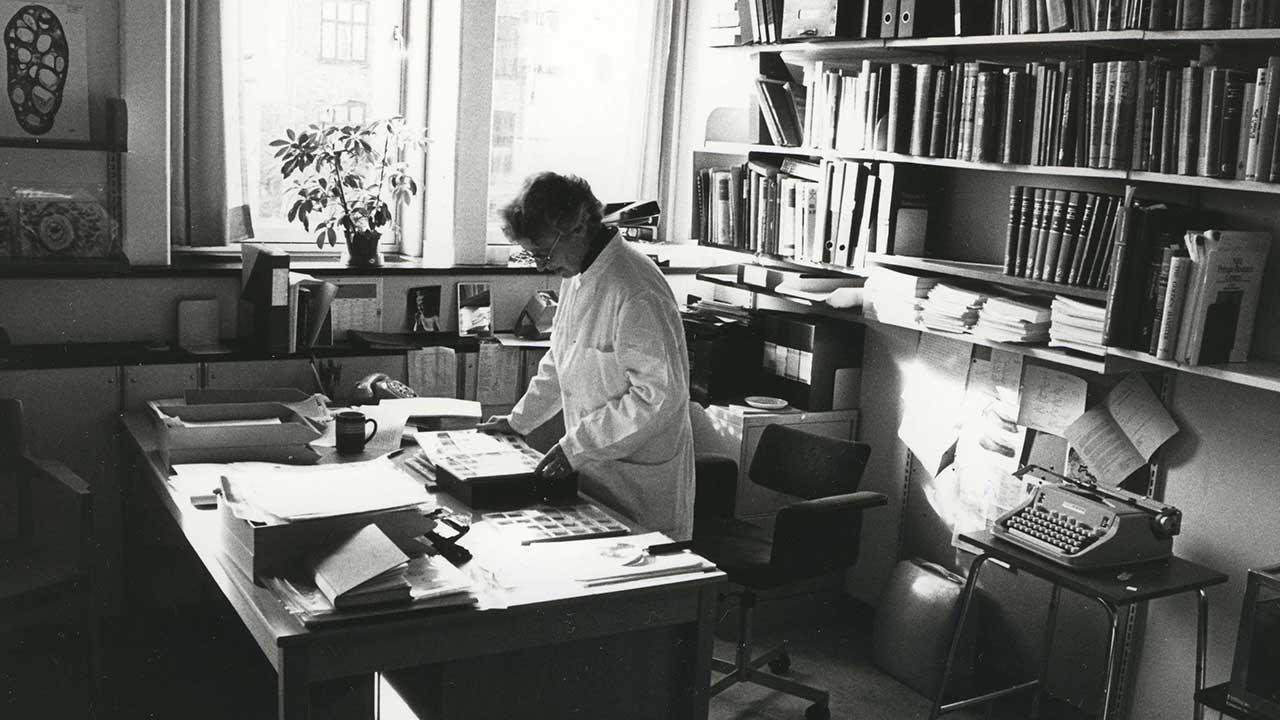

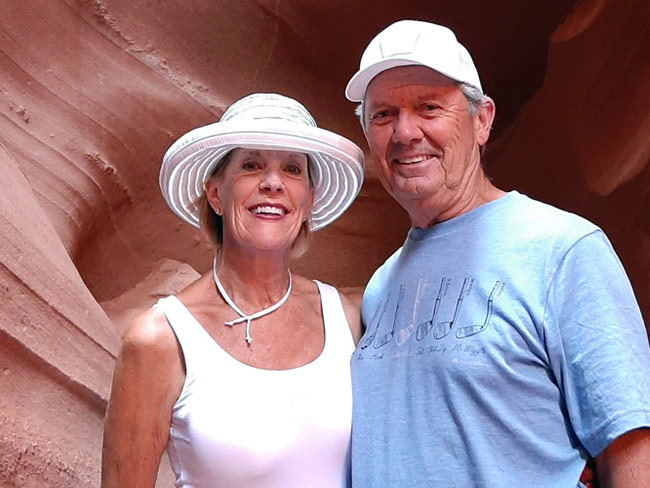

Dr. Peters (right) with colleagues at the International Conference of the International Planned Parenthood Federation in Santiago, Chile, 1967.

Because workers at the shipyards numbered in the thousands, doctors focused on disease prevention methods. Venereal disease was one of the many diseases that affected men and women workers. Dr. Peters knew that better-informed women could better protect their health. Her preventive approach to public health included placing venereal disease educational materials in all the women’s restrooms and shipyard newspapers.

“Literature, folders, as well as booklets, supplied by the Public Health Department, were made easily available in wooden racks which were hung in conspicuous places in every women’s restroom,” wrote Dr. Peters.

Afterward, she observed that many women came to the clinic asking for exams because of symptoms they read about in the literature provided. The campaign proved successful in reducing the cases of venereal diseases through the end of the war.

Continuing women’s health research

After the war, the health care plan that helped keep shipyard workers healthy, with the help of Dr. Peters, opened to the general public. Later, the health plan became known as Kaiser Permanente.

As for Dr. Peters, she went on to publish research about women’s health, focusing on reproductive biology and cancer until her retirement in 1980. She died in 2009 at the age of 97.

Since those early years, we’ve continued making discoveries that protect women’s health. For example:

- Our researchers helped develop an analytical tool for identifying people at risk of contracting HIV.

- Kaiser Permanente senior research scientist Erica Gunderson, PhD, brought awareness to how pregnancy may affect women’s heart health.

- Pregnancy and postpartum challenges led Kaiser Permanente to meet the needs of new moms and families by providing timely advice and care.

- Research from Kaiser Permanente found mammograms helped spot women who are at higher risk for heart attack, stroke, or cardiovascular disease.