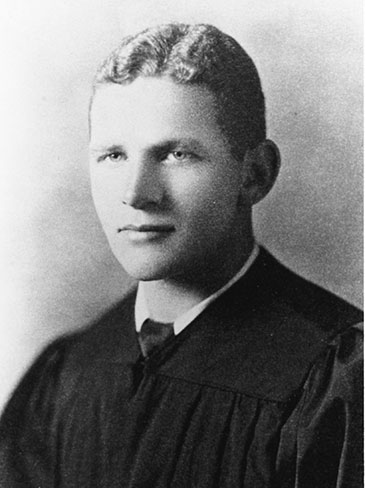

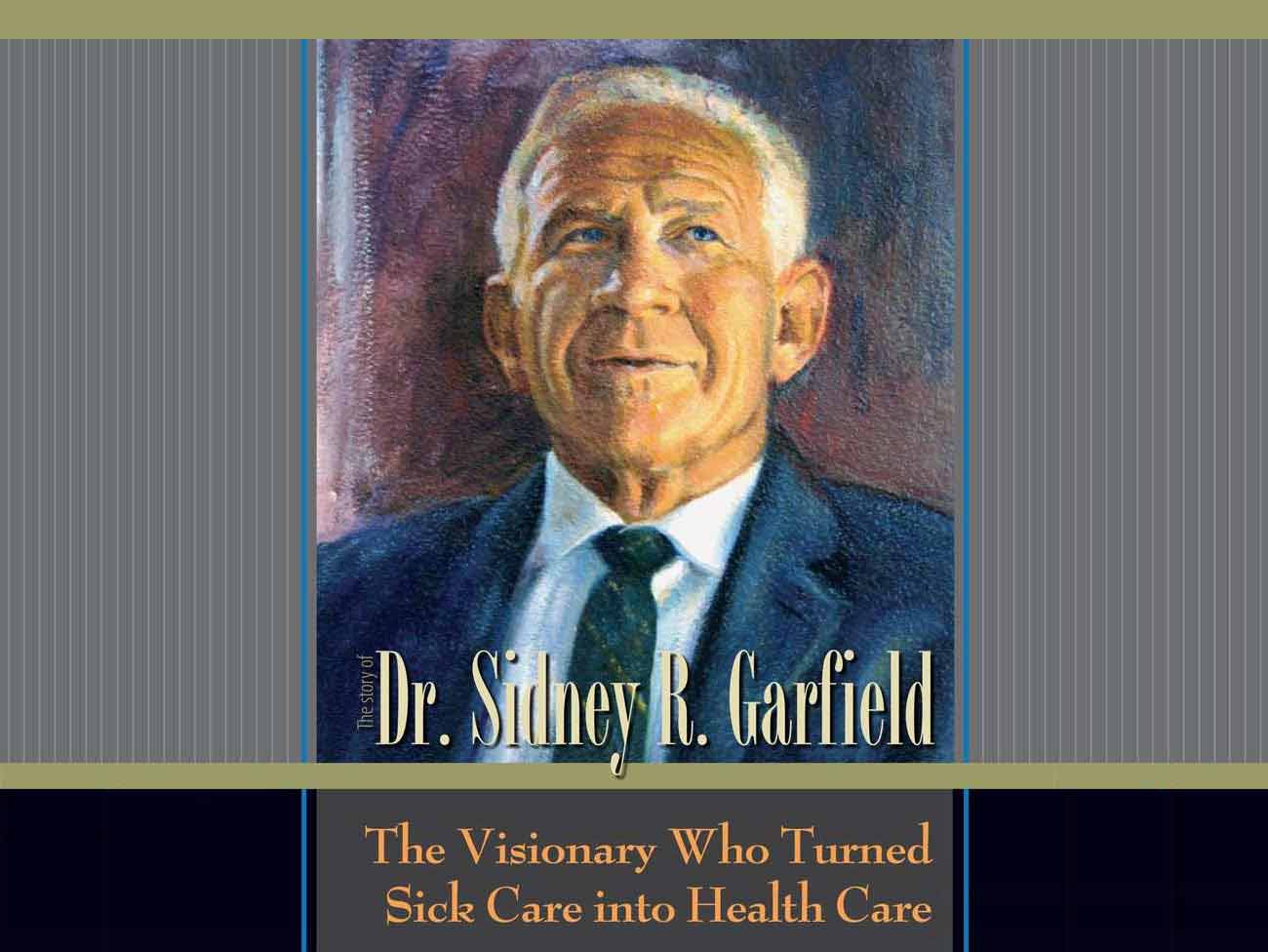

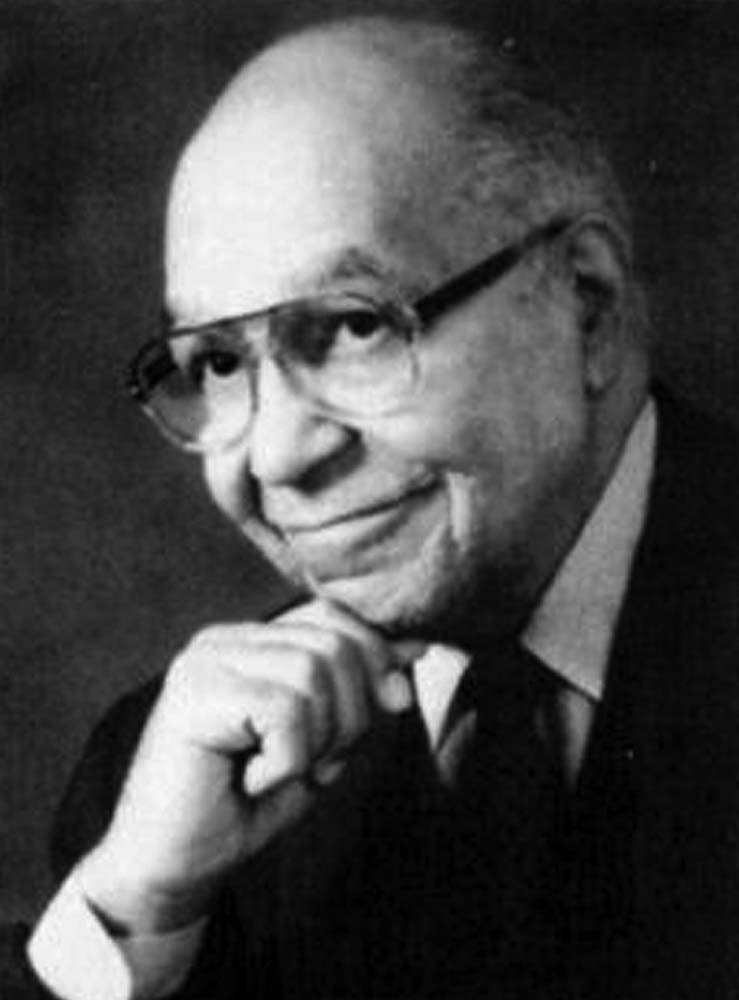

Sidney R. Garfield, MD: Pioneer of modern health care

Kaiser Permanente’s co-founding physician spread prepaid care and the idea that doctors should help keep people healthy — not just treat them when they’re sick.

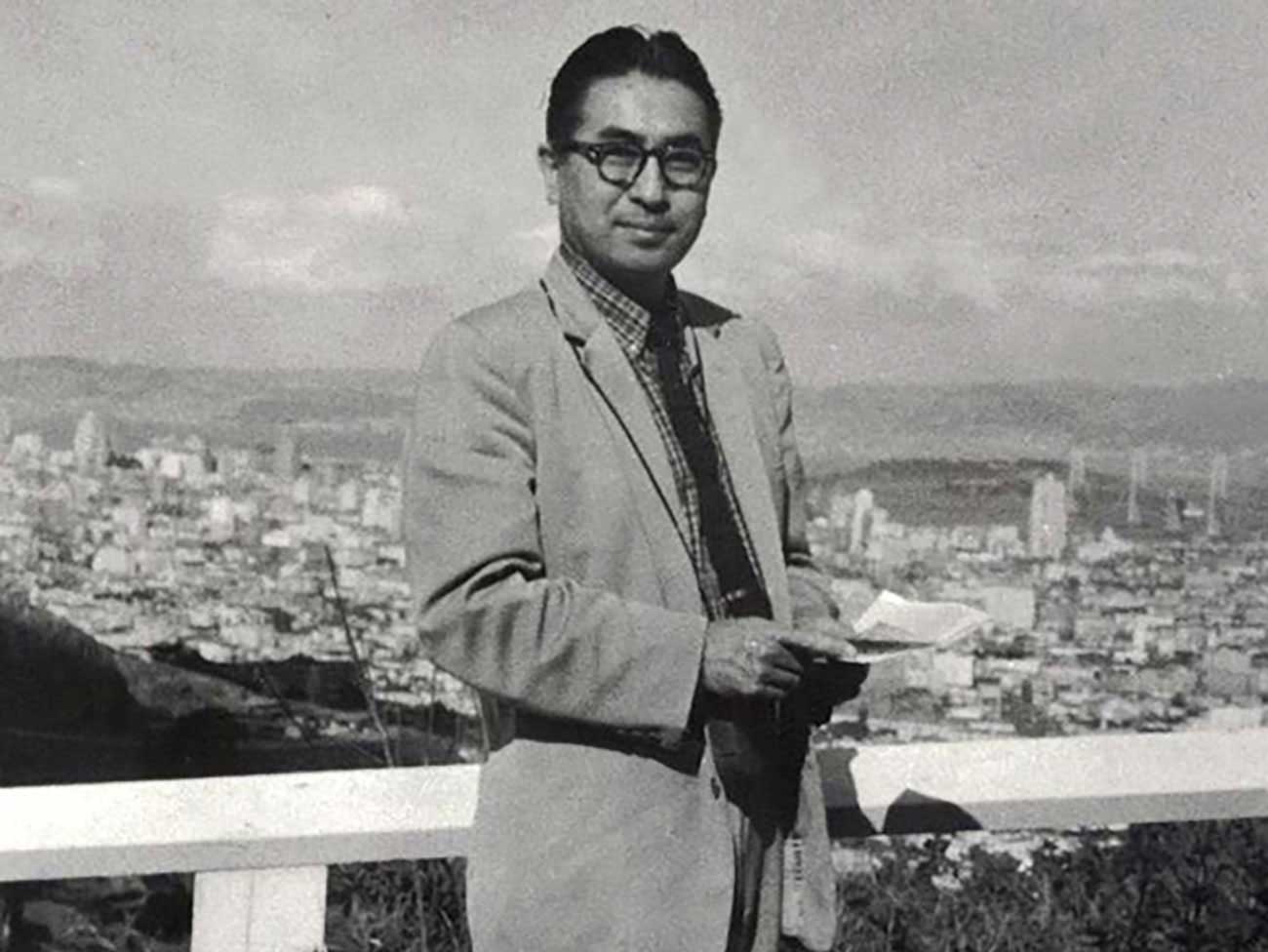

Dr. Sidney R. Garfield and Henry J. Kaiser, co-founded Kaiser Permanente. They introduced the country to a revolutionary model for integrated care and coverage.

Sidney Roy Garfield, MD, was a health care pioneer.

He believed in healthier lifestyles with annual checkups and preventive measures. He also promoted the early use of electronic health records.

He and industrialist Henry J. Kaiser co-founded Kaiser Permanente. They aimed to create a health care model that kept people well.

1906 to 1932: Early life and education

Garfield was born on April 17, 1906, in Elizabeth, New Jersey. His parents, Isaac and Bertha, were Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe.

Isaac ran a supply store for dock workers, sailors, and their families. Garfield, his mom, his dad, and his older sister Sally, lived above the store.

When he was in high school, Garfield wanted to be an architect. At his parents’ request, he chose to pursue medicine instead.

He got his undergraduate degree from the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. He went to medical school at the University of Iowa, and graduated in 1928.

Reflecting on the moment of deciding to study medicine, Garfield later remarked, “Something good comes out of everything.”

1933 to 1938: Providing care to builders of the Colorado River Aqueduct

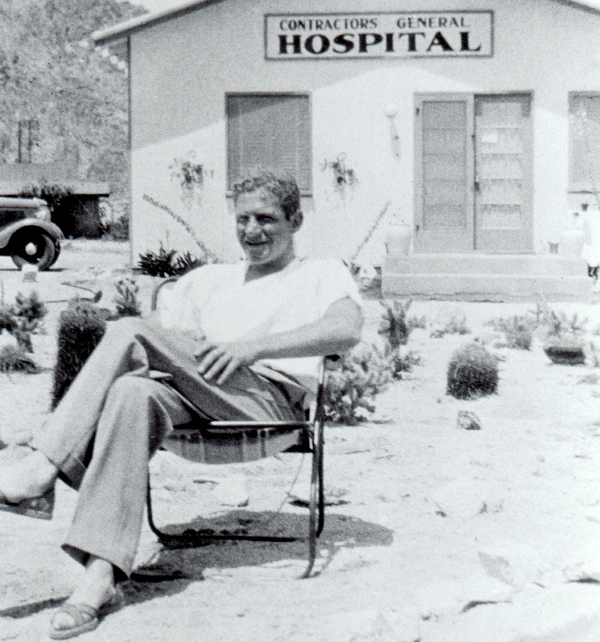

In 1933, when Dr. Garfield was finishing up his hospital residency in Los Angeles, he learned about the Colorado River Aqueduct project. It aimed to bring water from the Colorado River to Los Angeles.

Dr. Garfield reached out to the contractors. He learned that the project required a large workforce of about 5,000 people in a remote desert in Southern California. The workers would need on-site medical care.

The contractors offered Dr. Garfield a contract to provide care. He accepted and moved out to the desert.

He borrowed money to build and open a small hospital near the jobsite. The hospital was known as Contractors General Hospital. He also hired a nurse, Elizabeth “Betty” Runyen.

Dr. Garfield initially used a fee-for-service payment model at the hospital. In this model, doctors got paid for each service they provided. In the 1930s, nearly all doctors used this model.

Workers at the construction site faced many dangers and risks to health on the job. These included explosions, rock falls, nail punctures, and dehydration. Dr. Garfield and Runyen treated their injuries and prioritized workers’ wellness using preventive care methods not covered by insurance.

Dr. Garfield and his team also accepted sick or injured workers even when their insurance refused coverage. This put the hospital’s future at risk.

A new way of doing business

Dr. Garfield had become friends with Harold Hatch, an insurance agent. Hatch had an idea to help fix the hospital’s financial troubles. He suggested workers agree to voluntarily have a fixed amount deducted from their paycheck each week for all medical care. Since the care was prepaid, workers could receive all the care they needed.

The idea worked, and the hospital’s finances improved. Dr. Garfield and Runyen could now focus on preventive care. They taught workers about safety and hygiene. They encouraged workers to keep hard hats on and to stay hydrated. They also instructed workers to keep their area clear of nails and dangerous items.

Their efforts helped reduce injuries and costs. Dr. Garfield opened more hospitals and hired more staff. The growth reduced stress on the first hospital and helped workers receive more timely care.

“At the end of the 5-year contract, we had built and paid for 3 small hospitals and given those workers a lot of good medical care,” Dr. Garfield recalled later in life. “We were all better off if the workers remained well, and we were able to give them the services that they needed.”

1938 to 1941: The next experiment ― Grand Coulee Dam

As the aqueduct project was ending, Dr. Garfield got a call from Alonzo B. Ordway. Ordway was a construction manager for Henry J. Kaiser’s construction company, which was involved with the aqueduct project.

Ordway asked Dr. Garfield if he knew Kaiser. Dr. Garfield said he did not. Ordway explained that Kaiser wanted him to provide care for workers building the Grand Coulee Dam in Washington state.

When Dr. Garfield toured the jobsite in Mason City, Washington, with Kaiser’s son Edgar, he saw a community of 15,000 workers and their families. He understood the opportunity to deliver care for a community in one location. He accepted the contract and hired a team of doctors and nurses.

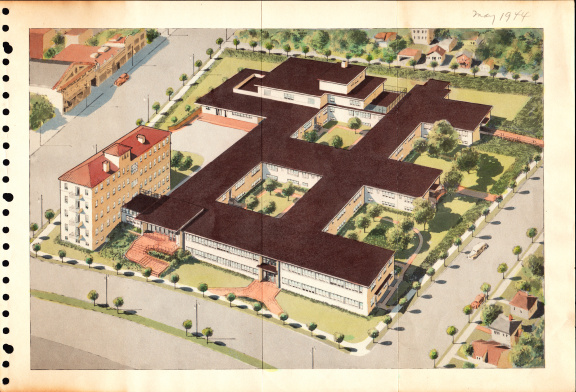

Dr. Garfield and his team planned to work out of the Mason City Hospital. Henry J. Kaiser Co., Ltd. had received the hospital as part of the dam contract. However, the hospital was poorly designed. Union workers in the area cited poor care and had lost trust in any health plan. Dr. Garfield believed that renovating the Mason City Hospital and providing excellent care would help rebuild trust with workers.

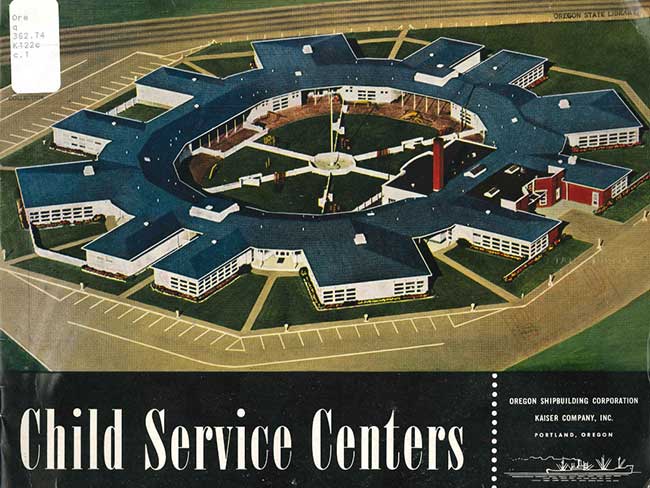

The renovations were finished in the summer of 1938. The hospital featured an integrated design — putting specialty care, a pharmacy, a clinic, and other care departments in a single building. Learning from his experiences with the Colorado River Aqueduct project, Dr. Garfield introduced a prepayment family plan. Workers prepaid a small weekly fee to cover medical care for themselves and their family.

When Henry J. Kaiser arrived for a visit, the 2 men spent the whole day talking about the health plan. Kaiser showed a lot of interest in its potential. "If your plan achieves even half of what you claim, it should be available to every person in this country,” Kaiser remarked.

The health plan for workers and families was a success. It provided coverage for injuries, illnesses, and preventive care, ensuring workers and their families got the right care at the right time.

Like his previous job in the desert, the Grand Coulee job was also a temporary contract for Dr. Garfield. But he often discussed what could be possible for the health plan with colleagues.

“We’d get together at Coulee at nighttime and talk about what we could do in a permanent community where (the health plan continued),” Dr. Garfield recalled.

Dr. Garfield planned to continue practicing surgery but wanted to refresh his skills and training first. He returned to the University of Southern California Medical School and taught surgery at LA County Hospital.

1941 to 1945: A call to duty

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese military attacked Pearl Harbor, prompting America’s entry into World War II. Like many other people, Dr. Garfield was shocked.

Feeling a sense of duty and commitment to the cause, Dr. Garfield volunteered for the Army.

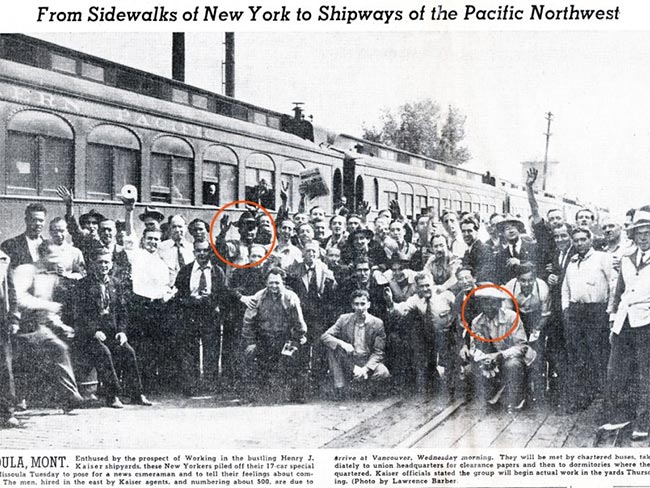

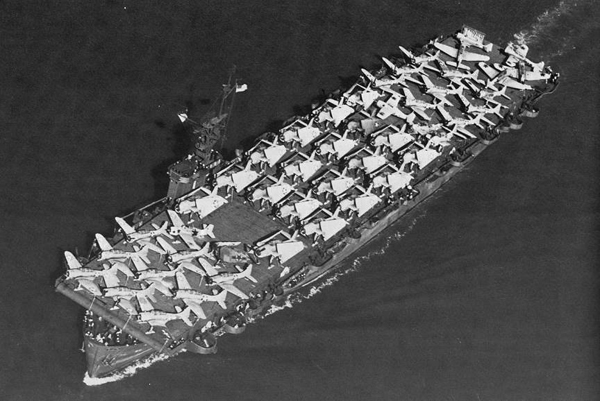

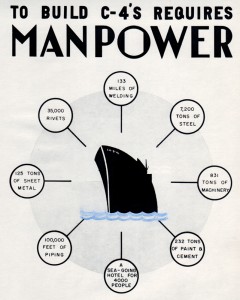

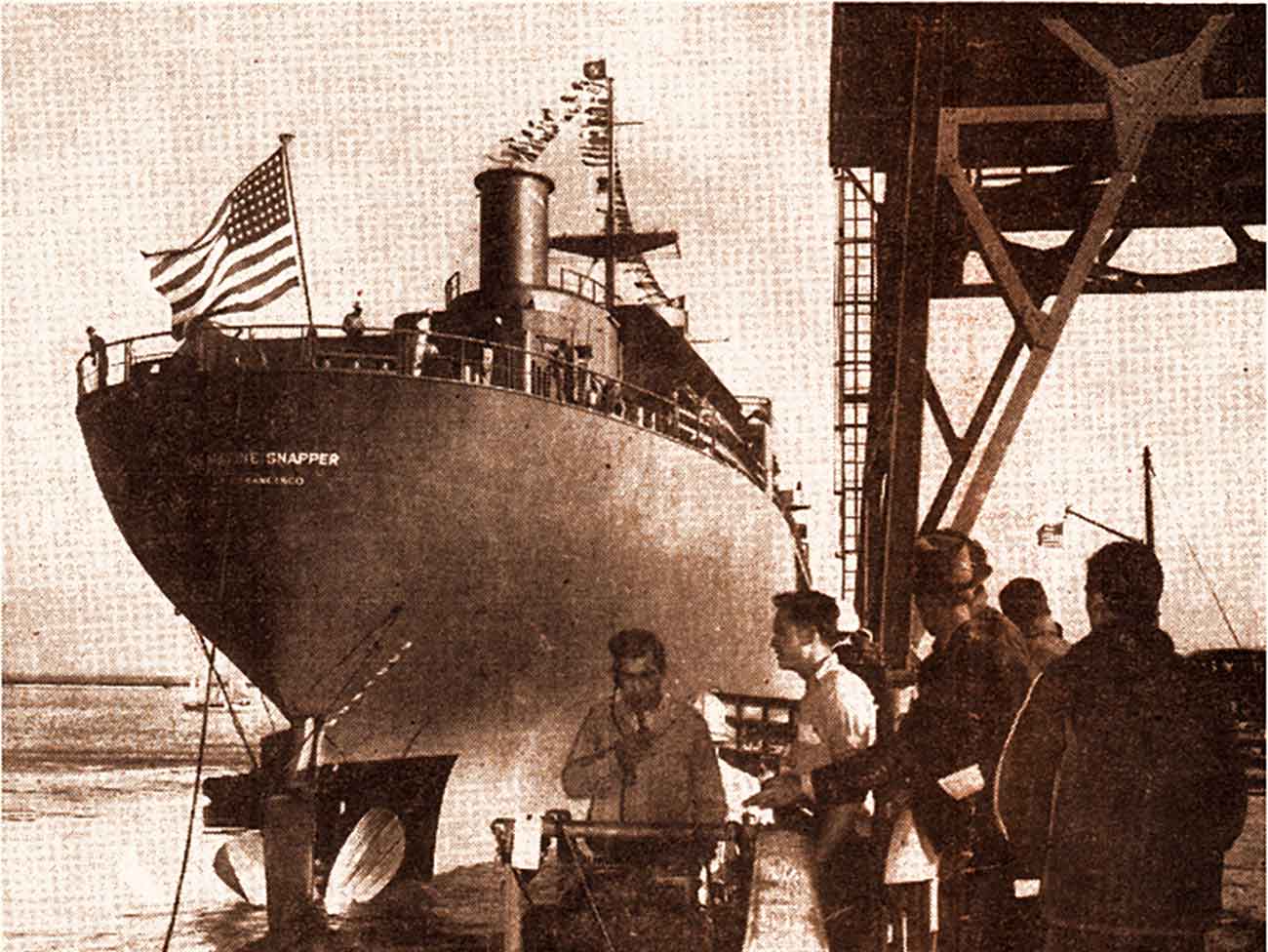

However, Kaiser had other plans for Dr. Garfield. He wanted him to create a health plan for the thousands of workers building wartime cargo ships at the Kaiser shipyards.

At Kaiser’s request, President Franklin D. Roosevelt released Dr. Garfield from his Army service. Dr. Garfield got to work creating a shipyard health plan.

The home front’s health plan

Thousands of workers arrived at Kaiser’s shipyards to be part of America’s defense industries. Thousands of women also joined the home front, which changed the American workforce. Dr. Garfield brought together a group of doctors and nurses to provide care for the shipyard workers and their families.

They called the plan the Permanente Health Plan and made it available at all of Kaiser’s shipyards. More than 200,000 people (workers and their family members) were plan members.

Like at the Grand Coulee Dam, members prepaid a weekly fee. In exchange, they received preventive care in addition to care for common illnesses and injuries.

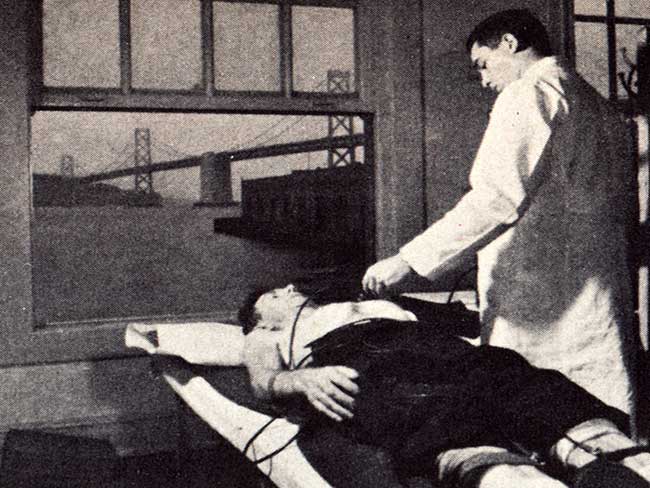

To support the health plan, Kaiser’s construction teams renovated the Fabiola Hospital in Oakland, California. It became the Permanente Oakland Hospital and opened in 1942 to care for the shipyards’ health plan members.

Dr. Garfield and Kaiser didn’t stop at one hospital. They also built a field hospital near the shipyard, and another hospital for shipyard workers in the Pacific Northwest. That hospital was named Northern Permanente Hospital.

While many hospitals around the country at that time cared for Black and white patients separately, the wards at all of Kaiser’s and Garfield’s hospitals were integrated from the moment the doors opened.

1945 to 1981: America’s new health plan

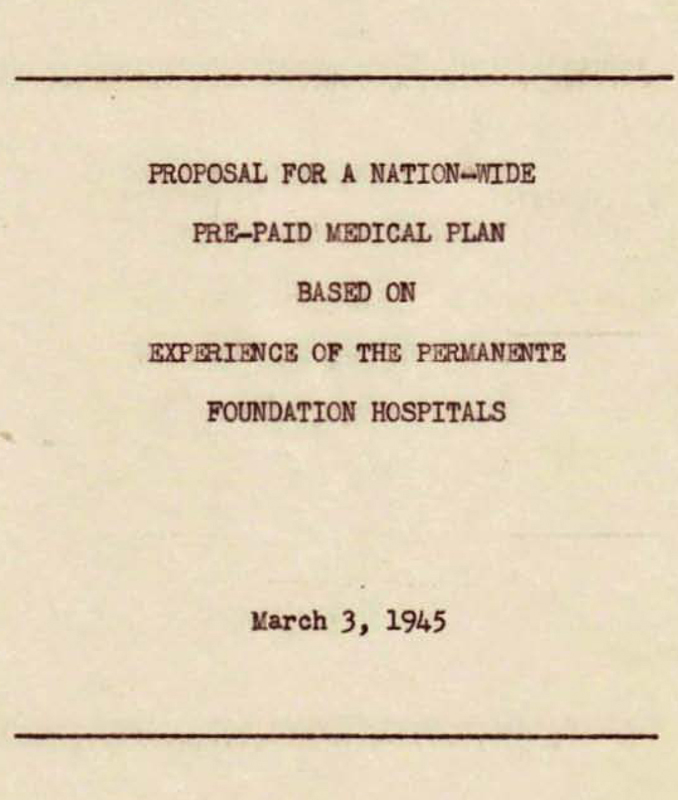

When World War II wound down in 1945, demand for ships slowed. Kaiser’s shipyards began closing, and health plan membership dropped.

And yet Dr. Garfield and Kaiser saw in their shipyard health plan a new vision for health care in America. They wanted to continue delivering care in this new way — using prepayment, group practice, and a focus on injury and illness prevention.

Together, Dr. Garfield and Kaiser opened the Permanente Health Plan to the public on July 21, 1945.

In 1953, the Permanente Health Plan adopted a new name: Kaiser Permanente.

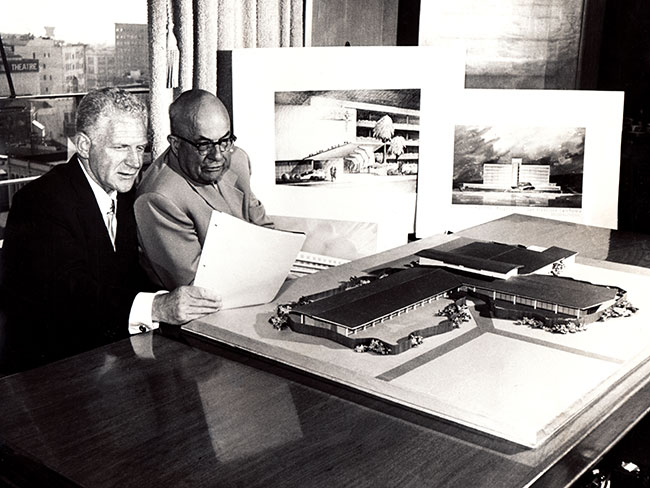

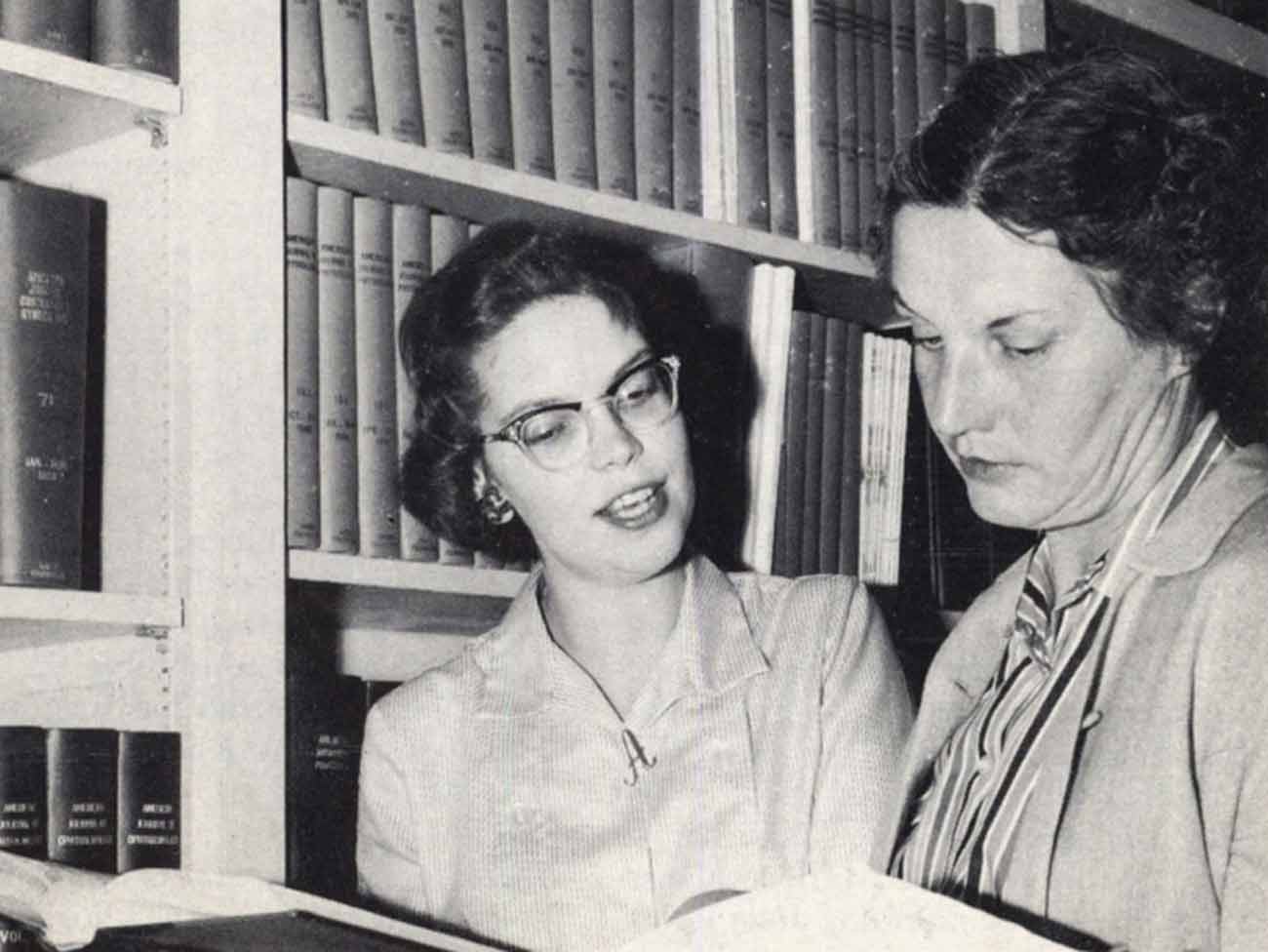

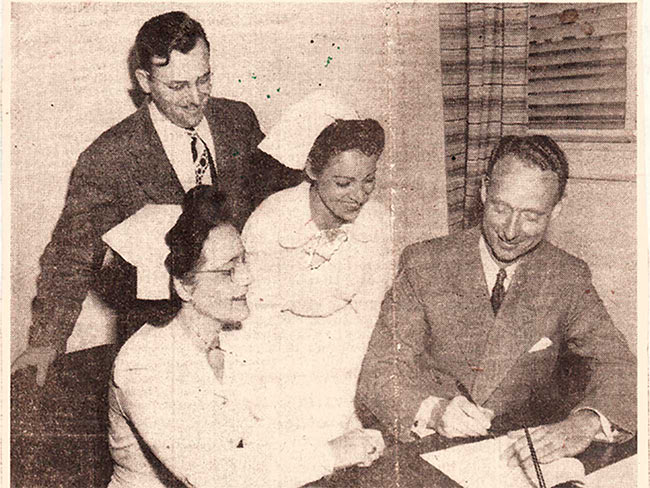

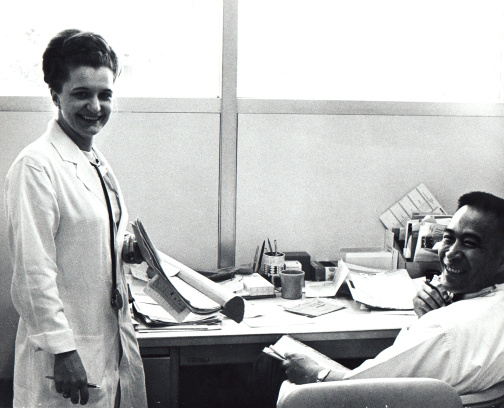

Dr. Garfield (left) and Kaiser review hospital plans in 1953. On the table is a model of the innovative Walnut Creek Hospital, which featured bedside push-button consoles for patients and an advanced surgical suite.

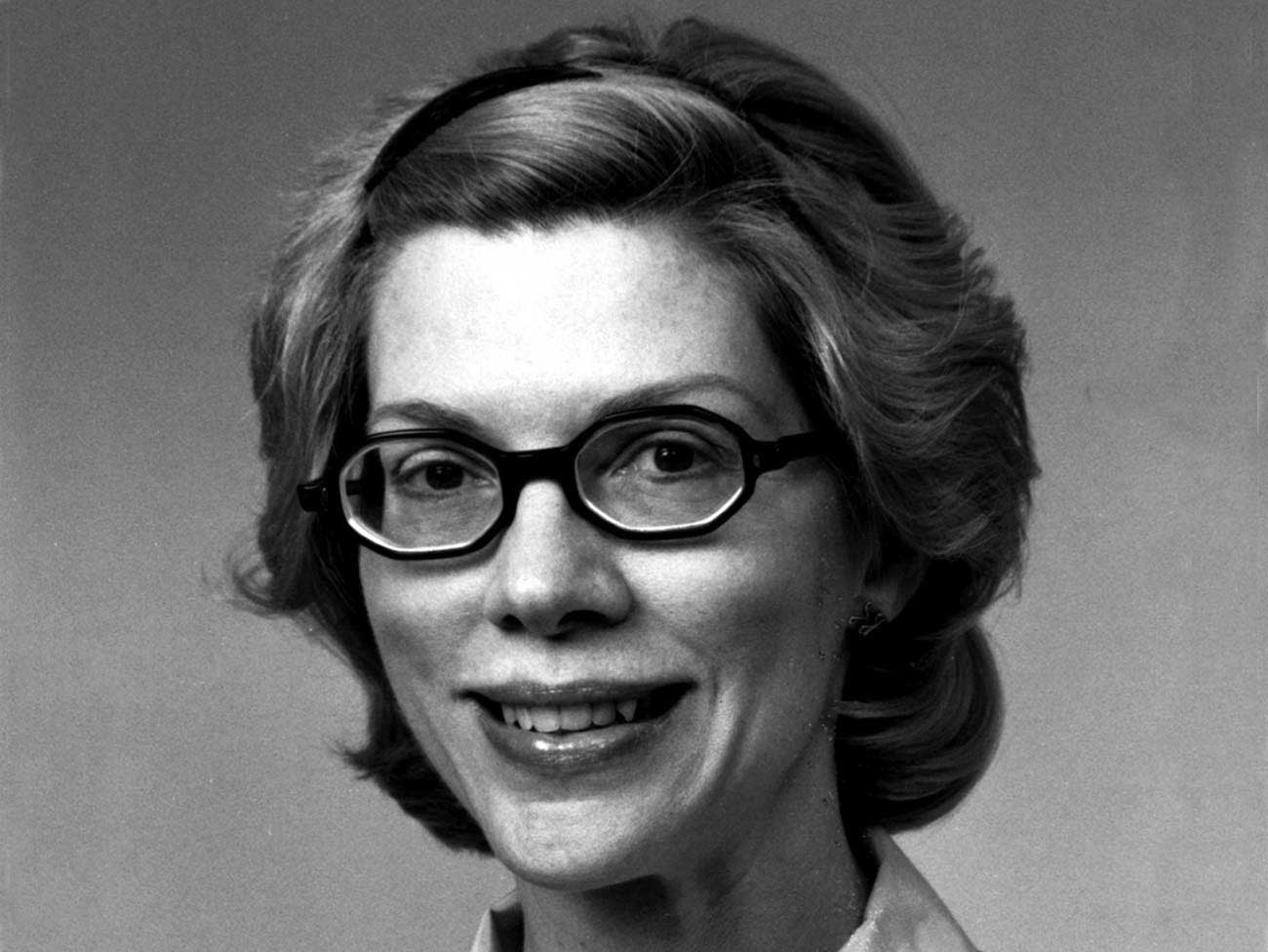

1981 to present: Dr. Garfield’s legacy of total health

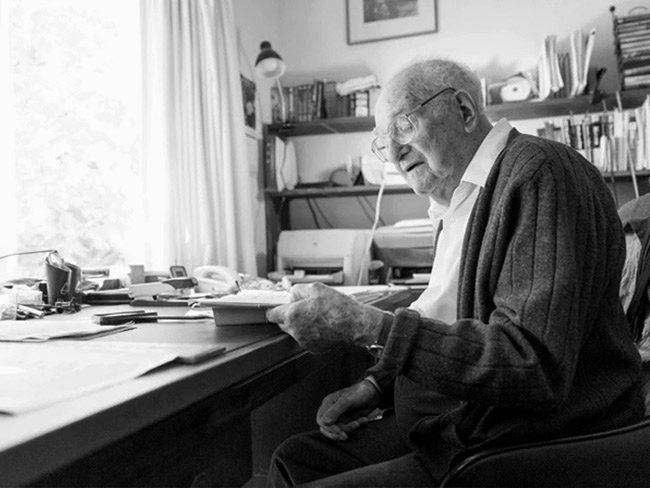

In 1981, Dr. Garfield launched a new project with strong ties to the fundamental idea that helped launch Kaiser Permanente ― the belief that health care should keep people healthy and not just treat them when they’re sick or injured. His new endeavor became known as the Total Health Care Project.

The project addressed a mismatch in the health care system. More people were becoming health-conscious, but the health care system still focused primarily on illness. Dr. Garfield’s project was a long-term study using information gathered by his team.

The team asked health plan members to volunteer for a health assessment. By gathering answers to health questions over each member’s lifetime, Dr. Garfield hoped to develop a balanced spectrum of health care services.

Dr. Garfield died in 1984 before the Total Health Care Project finished. But his bold ideas would take another form at Kaiser Permanente decades later.

Our 2004 ad campaign focused on the term “total health,” evolving it further from Dr. Garfield’s original vision. Total health now included care that considers all aspects of a person's state of being — body, mind, and spirit.

That same year, we launched our Total Health programs. The programs encouraged members to walk daily and be active. They also asked members to take health assessments and join health education classes.

Dr. Garfield’s lifetime dedication to improving health care in America had lasting impacts on the total health of Kaiser Permanente members and the people in our communities. His efforts continue to influence our work and support our mission today.

-

Social Share

- Share Sidney R. Garfield, MD: Pioneer in Modern American Health Care on Pinterest

- Share Sidney R. Garfield, MD: Pioneer in Modern American Health Care on LinkedIn

- Share Sidney R. Garfield, MD: Pioneer in Modern American Health Care on Twitter

- Share Sidney R. Garfield, MD: Pioneer in Modern American Health Care on Facebook

- Print Sidney R. Garfield, MD: Pioneer in Modern American Health Care

- Email Sidney R. Garfield, MD: Pioneer in Modern American Health Care

April 30, 2025

A history of trailblazing nurses

Nursing pioneers lay the foundation for the future of Kaiser Permanente …

September 19, 2024

First look at new Lakewood facilities

New medical offices will enhance the health care experience for members …

May 3, 2024

Henry J. Kaiser: America’s health care visionary

Kaiser was a major figure in the construction, engineering, and shipbuilding …

April 8, 2024

Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream is alive at Kaiser Permanente

Greg A. Adams, chair and chief executive officer of Kaiser Permanente, …

February 13, 2024

A legacy of life-changing community support and partnership

The Kaiser Permanente Watts Counseling and Learning Center started as a …

February 2, 2024

Expanding medical, social, and educational services in Watts

Kaiser Permanente opens medical offices and a new home for the Watts Counseling …

October 17, 2023

How Kaiser Permanente evolved

Sidney R. Garfield, MD, and Henry J. Kaiser came together to pioneer an …

September 13, 2023

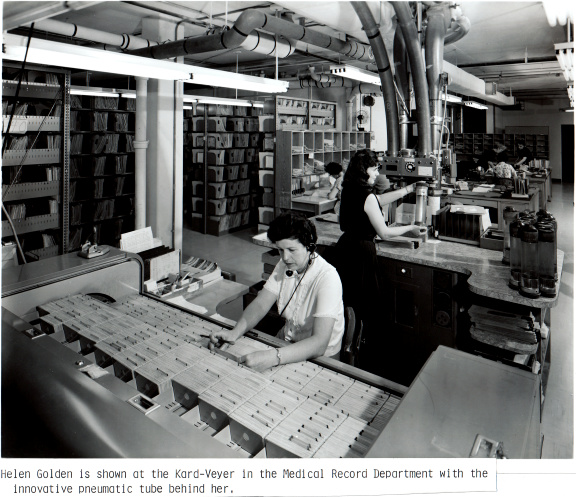

Transforming the medical record

Kaiser Permanente’s adoption of disruptive technology in the 1970s sparked …

May 2, 2023

Women lead an industrial revolution at the Kaiser Shipyards

Early women workers at the Kaiser shipyards diversified home front World …

April 25, 2023

Hannah Peters, MD, provides essential care to ‘Rosies’

When thousands of women industrial workers, often called “Rosies,” joined …

November 11, 2022

A history of leading the way

For over 75 innovative years, we have delivered high-quality and affordable …

November 11, 2022

Pioneers and groundbreakers

Learn about the trailblazers from Kaiser Permanente who shaped our legacy …

November 11, 2022

Our integrated care model

We’re different than other health plans, and that’s how we think health …

November 11, 2022

Our history

Kaiser Permanente’s groundbreaking integrated care model has evolved through …

October 14, 2022

Contact Heritage Resources

October 6, 2022

We’re a Fast Company Innovation by Design winner

Kaiser Permanente is the first health care organization to win Design Company …

October 1, 2022

Innovation and research

Learn about our rich legacy of scientific research that spurred revolutionary …

May 26, 2022

Nurse practitioners: Historical advances in nursing

A doctor shortage in the late 1960s and an innovative partnership helped …

September 10, 2021

‘Baby in the drawer’ helped turn the tide for breastfeeding

This innovation in rooming-in allowed newborns to stay close to mothers …

August 25, 2021

Kaiser Permanente’s history of nondiscrimination

Our principles of diversity and our inclusive care began during World War …

July 22, 2021

A long history of equity for workers with disabilities

In Henry J. Kaiser’s shipyards, workers were judged by their abilities, …

June 2, 2021

Path to employment: Black workers in Kaiser shipyards

Kaiser Permanente, Henry J. Kaiser’s sole remaining institutional legacy, …

February 22, 2021

The Permanente Richmond Field Hospital

Forlorn and all but forgotten, it played a proud role during the World …

September 28, 2020

A legacy of disruptive innovation

Proceeds from a new book detailing the history of the Kaiser Foundation …

August 26, 2020

Kaiser Permanente’s pioneering nurse-midwives

The 1970s nurse-midwife movement transformed delivery practices.

July 30, 2020

Books and publications about our history

Interested in learning more about the history of Kaiser Permanente and …

May 18, 2020

Nurses step up in crises

Kaiser Permanente nurses have been saving lives on the front lines since …

November 8, 2019

Swords into stethoscopes — veterans in health professions

Kaiser Permanente has actively hired veterans in all capacities since World …

August 28, 2019

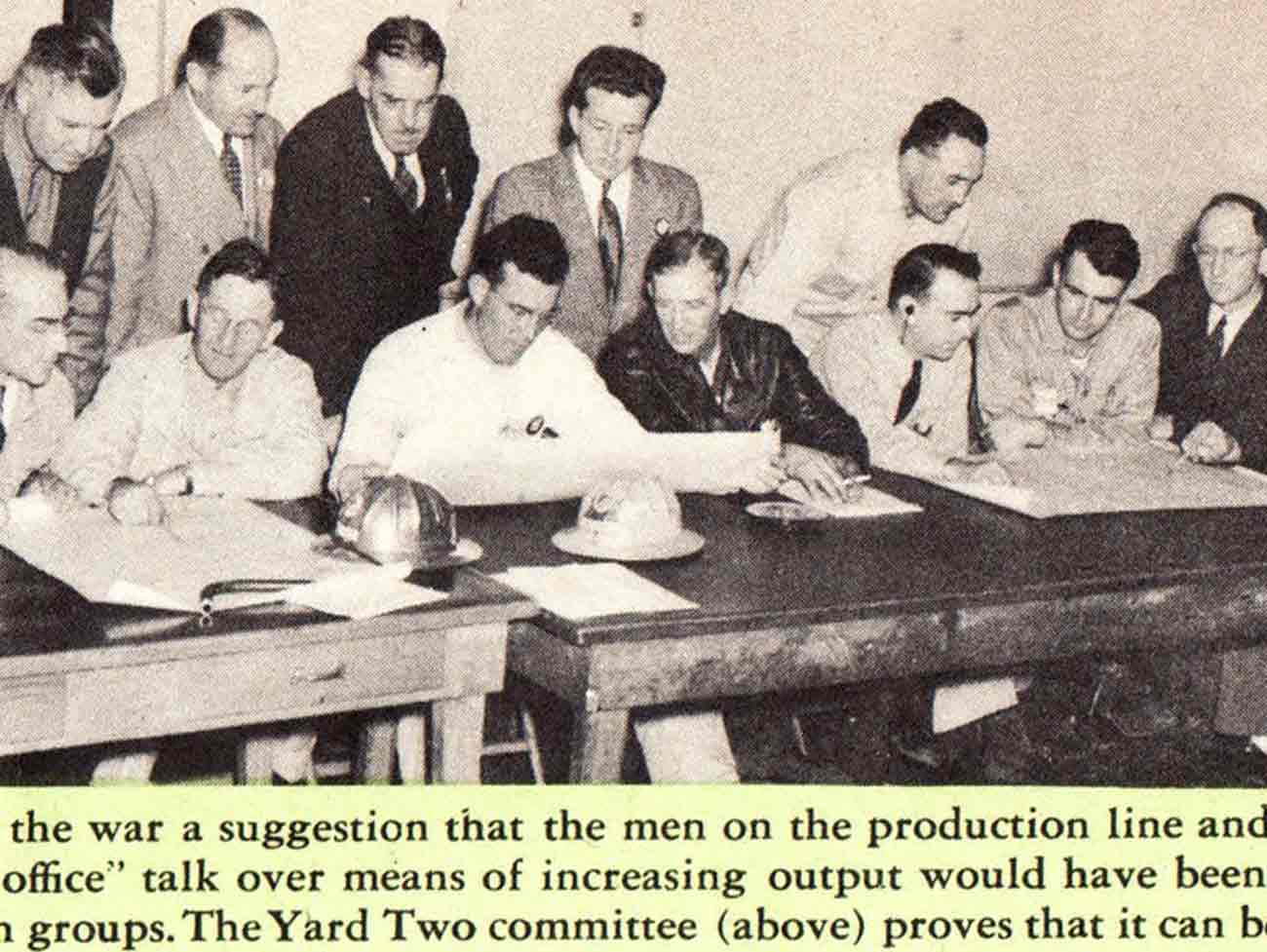

When labor and management work side by side

From war-era labor-management committees to today’s unit-based teams, cooperation …

August 2, 2019

Thriving with 1960s-launched KFOG radio

Kaiser Broadcasting radio connected listeners, while TV stations brought …

June 5, 2019

Breaking LGBT barriers for Kaiser Permanente employees

“We managed to ultimately break through that barrier.” — Kaiser Permanente …

March 29, 2019

Equal pay for equal work

Kaiser shipyards in Oregon hired the first 2 female welders at equal pay …

February 5, 2019

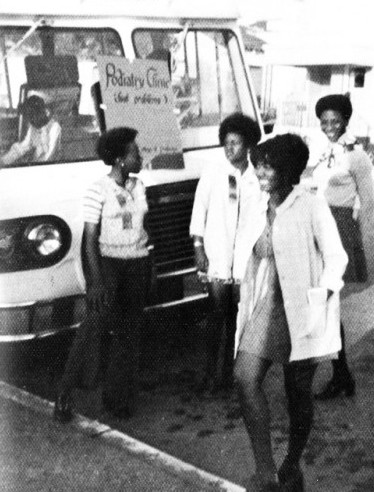

Mobile clinics: 'Health on wheels'

Kaiser Permanente mobile health vehicles brought care to people, closing …

December 10, 2018

Southern comfort — Dr. Gaston and The Southeast Permanente Medical Group

Local Atlanta physicians built community relationships to start Kaiser …

May 30, 2018

John Graham Smillie, MD, pediatrician and innovator

Celebrating the life of a pioneering pediatrician who inspired the baby …

April 30, 2018

Nursing pioneers leads to a legacy of leadership

Kaiser Foundation School of Nursing students learned a new philosophy emphasizing …

April 19, 2018

Wasting nothing: Recycling then and now

Environmentalism was a common practice at the Kaiser shipyards long before …

April 12, 2018

Harold Hatch, health insurance visionary

The founding of Kaiser Permanente's concept of prepaid health care in the …

March 26, 2018

5 physicians who made a difference

Meet 5 outstanding doctors who advanced the practice of medical care with …

March 13, 2018

Henry J. Kaiser and the new economics of medical care

Kaiser Permanente’s co-founder talks about the importance of building hospitals …

March 8, 2018

Slacks, not slackers — women’s role in winning World War II

Women who worked in the Kaiser shipyards helped lay the groundwork for …

February 22, 2018

The amazing true story of Park Ranger Betty Reid Soskin

She is the oldest national park ranger in the country with a legacy of …

December 19, 2017

From boats to books: A history of Kaiser Permanente’s medical libraries

Kaiser Permanente librarians are vital in helping clinicians remain updated …

November 7, 2017

Patriot in pinstripes: Honoring veterans, home front, and peace

Henry J. Kaiser's commitment to the diverse workforce on the home front …

October 12, 2017

An experiment named Fabiola

Health care takes root in Oakland, California.

September 29, 2017

Harbor City Hospital: Beachhead for labor health care

The story of Kaiser Permanente's South Bay Medical Center finds its roots …

August 15, 2017

Sidney R. Garfield, MD, on medical care as a right

Hear Kaiser Permanente’s physician co-founder talk about what he learned …

August 10, 2017

‘Good medicine brought within reach of all'

Paul de Kruif, microbiologist and writer, provides early accounts of Kaiser …

July 14, 2017

Kaiser’s role in building an accessible transit system

Harold Willson, an employee, and an advocate for accessible transportation, …

July 7, 2017

Mending bodies and minds — Kabat-Kaiser Vallejo

The expanded new location provided care to a greater population of members …

June 23, 2017

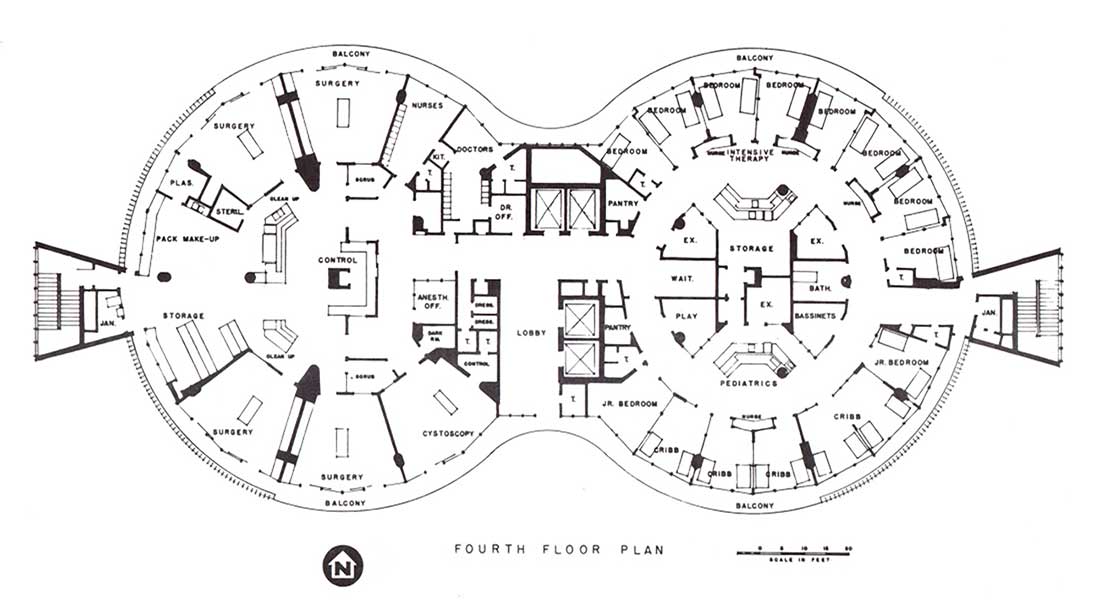

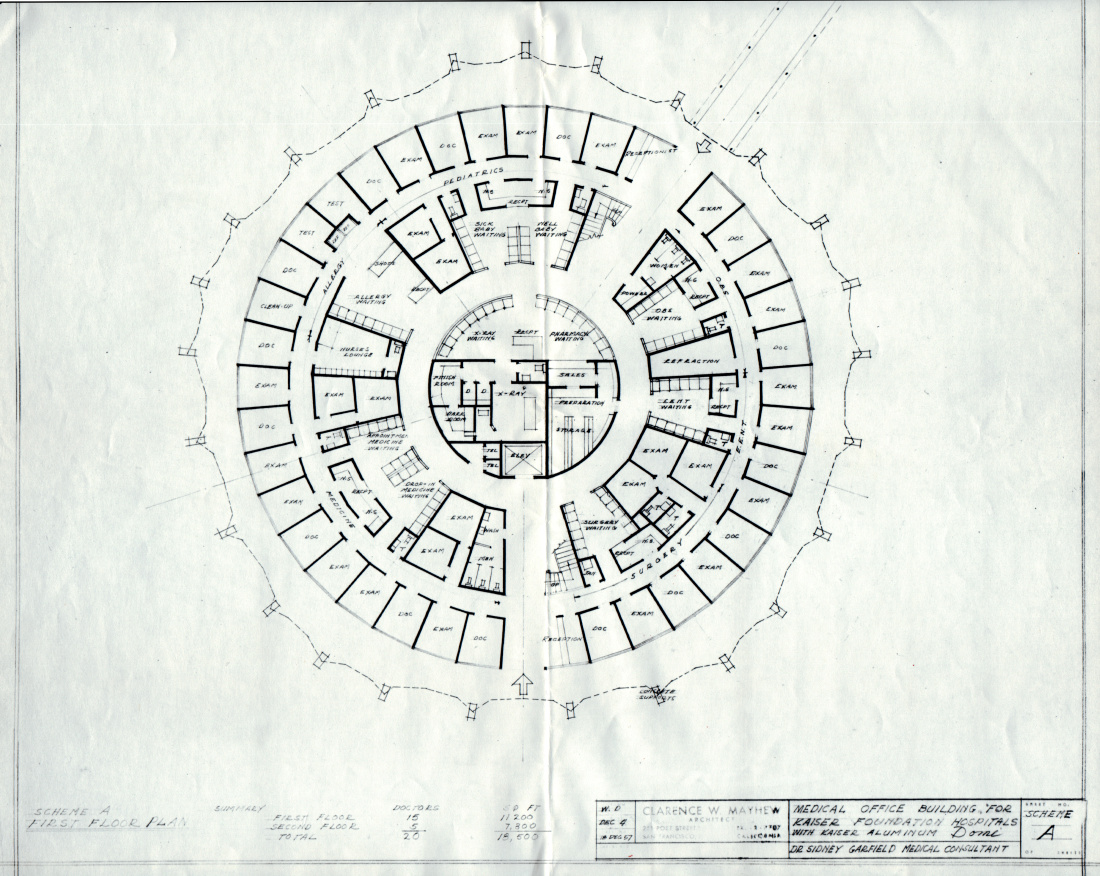

No getting round it: An innovative approach to building design

Kaiser Permanente incorporated innovative circular architectural designs …

June 14, 2017

Kabat-Kaiser: Improving quality of life through rehabilitation

When polio epidemics erupted, pioneering treatments by Dr. Herman Kabat …

June 9, 2017

Edmund (Ted) Van Brunt, pioneer of electronic health records, dies at age …

Throughout his career, Dr. Van Brunt applied computers and databases in …

May 4, 2017

How a Kaiser Permanente nurse transformed health education

Kaiser Permanente's Health Education Research Center and Health Education …

March 22, 2017

Kaiser Permanente and Group Health Cooperative: Working together since …

The formation of Kaiser Permanente Washington comes from longstanding collaboration, …

March 7, 2017

Beatrice Lei, MD: From Shantou, China, to Richmond, California

She served as a role model and inspiration to the women physicians and …

March 1, 2017

Screening for better health: Medical care as a right

When industrial workers joined the health plan, an integrated battery of …

February 17, 2017

Experiments in radial hospital design

The 1960s represented a bold step in medical office architecture around …

February 3, 2017

Ellamae Simmons — trailblazing African American physician

Ellamae Simmons, MD, worked at Kaiser Permanente for 25 years, and to this …

January 27, 2017

Japanese-American doctors overcame internment setbacks

Despite restrictive hiring practices after World War II, Kaiser Permanente …

November 16, 2016

Betty Reid Soskin honored with lifetime achievement award

The California Studies Association presents the Carey McWilliams Award …

October 17, 2016

Kaiser Motors in Oakland — “We sell to make friends.”

In 1946 Henry J. Kaiser Motors purchased half a square block in downtown …

October 12, 2016

Kaiser’s geodesic dome clinic

There are hospital rounds, and there are round hospitals.

May 5, 2016

Male nursing pioneers

Groundbreaking male students diversify the Kaiser Foundation School of …

April 20, 2016

Henry J. Kaiser’s environmental stewardship

Since the 1940s, Kaiser Industries and Kaiser Permanente have a long history …

November 13, 2015

Dr. Morris Collen’s last book on medical informatics

The last published work of Morris F. Collen, MD, one of Kaiser Permanente’s …

October 29, 2015

From paper to pixels — the new paradigm of electronic medical records

Transitioning to electronic health records introduced new approaches, skills, …

September 23, 2015

Kaiser Permanente and NASA — taking telemedicine out of this world

Kaiser Permanente International designs, develop, and test a remote health …

July 22, 2015

Kaiser Permanente as a national model for care

Kaiser Permanente proposed a revolutionary national health care model after …

July 21, 2015

Kaiser Permanente's early support from labor

Experiencing the Kaiser Permanente health plan led labor unions to support …

July 20, 2015

Opening the Permanente plan to the public

On July 21, 1945, Henry J. Kaiser and Dr. Sidney Garfield offered the health …

July 1, 2015

Sculpture dedicated to Kaiser Nursing School

The Kaiser Foundation School of Nursing sculpture near Kaiser Oakland hospital …

May 6, 2015

Celebrating Betty Runyen — Kaiser Permanente’s ‘founding nurse’

In a desert hospital during the Great Depression, Betty Runyen overcame …

April 27, 2015

Eugene Hickman, MD — Pioneering Black physician

Dr. Hickman had a long career at Kaiser Permanente, becoming president …

April 24, 2015

2 historical reflections on Kaiser Permanente

April 2, 2015

Henry Kaiser’s escort carriers and the Battle of Leyte Gulf

January 9, 2015

The World War II Kaiser Richmond shipyard labor force

December 16, 2014

Henry J. Kaiser on veteran employment and benefits

December 11, 2014

Henry J. Kaiser, geodesic dome pioneer

July 23, 2014

Kaiser shipyards pioneered use of wonder drug penicillin

Though supplies for civilians were limited, Dr. Morris Collen’s wartime …

June 24, 2014

Kaiser Permanente's first hospital changes and grows

A collection of vintage photos that chronicle the evolution of Oakland …

June 20, 2014

Old hospital holds memories of Kaiser Permanente’s past

Rebuilt Oakland Medical Center to open for business.

May 13, 2014

Henry J. Kaiser sticks up for union labor at Brewster Aeronautical

May 5, 2014

Black nurses get together to forge their own future

California African American nurses organize in early 1970s to address health …

May 1, 2014

Beloved nurse earned place in Kaiser Permanente history

Jessie Cunningham, the first Black nursing supervisor at Oakland Medical …

February 18, 2014

Alva Wheatley: Champion of Kaiser Permanente diversity

Third in a series marking Black History Month.

January 31, 2014

Raleigh Bledsoe, MD: First Black radiologist west of Rockies

Dr. Bledsoe became the first Black physician for Southern California Permanente …

January 23, 2014

Kaiser's first labor attorney in the thick of union battles

Harry F. Morton was an instrumental figure at Henry J. Kaiser's side, setting …

October 16, 2013

Georgia cardiologist returns to Atlanta to start new Permanente group

Kaiser Permanente expands to the Southeast and builds community relations …

October 8, 2013

Northwest Region started small and grew fast

Kaiser Permanente remained and opened the Northwest Region after World …

October 7, 2013

The roots of Southern California Kaiser Permanente

Kaiser Permanente Southern California started from its roots at the Fontana …

September 23, 2013

Kaiser Permanente pioneered solar power in health facilities in 1980

Santa Clara Medical Center hosted a solar panel project in 1979 to demonstrate …

September 20, 2013

The Permanente Creek

Henry J. Kaiser's wife, Bess, admired the creek and its name, leading Kaiser …

September 19, 2013

Kaiser’s postwar suburbs designed for pedestrian safety and fitness

Model neighborhoods close to jobs and laid out with meandering lanes and …

September 18, 2013

The genesis of Kaiser Permanente Colorado

Utah miners, a strike, and the need for care were the ingredients to opening …

September 16, 2013

Physician-nurse team helps Permanente medicine through early days

Dr. Cecil Cutting and nurse Millie Cutting were among the first medical …

August 16, 2013

Dr. Charles M. Grossman, 1914–2013 — founding Northwest Permanente physician

In memoriam: Remembering and reflecting on a pioneering physician from …

August 2, 2013

Image of Rosie broadens to embrace African American women

Black women find new opportunities to elevate work status on the World …

July 15, 2013

Labor unions offer early support for nascent Permanente Health Plan

After World War II, the experience of the Kaiser Permanente Health Plan …

July 9, 2013

Kaiser Permanente Web presence rooted in past

The first Kaiser Permanente website launched in 1996, creating a new way …