Henry J. Kaiser: America’s health care visionary

Kaiser was a major figure in the construction, engineering, and shipbuilding industries. In co-founding Kaiser Permanente, he helped transform American health care systems and care delivery.

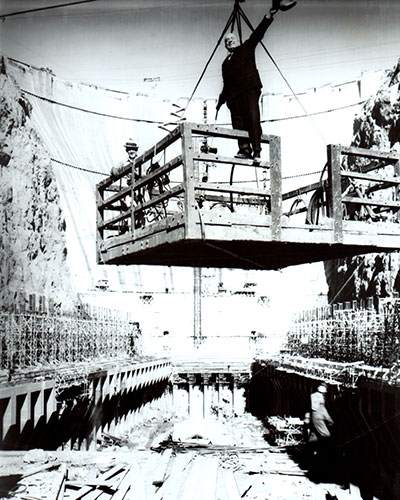

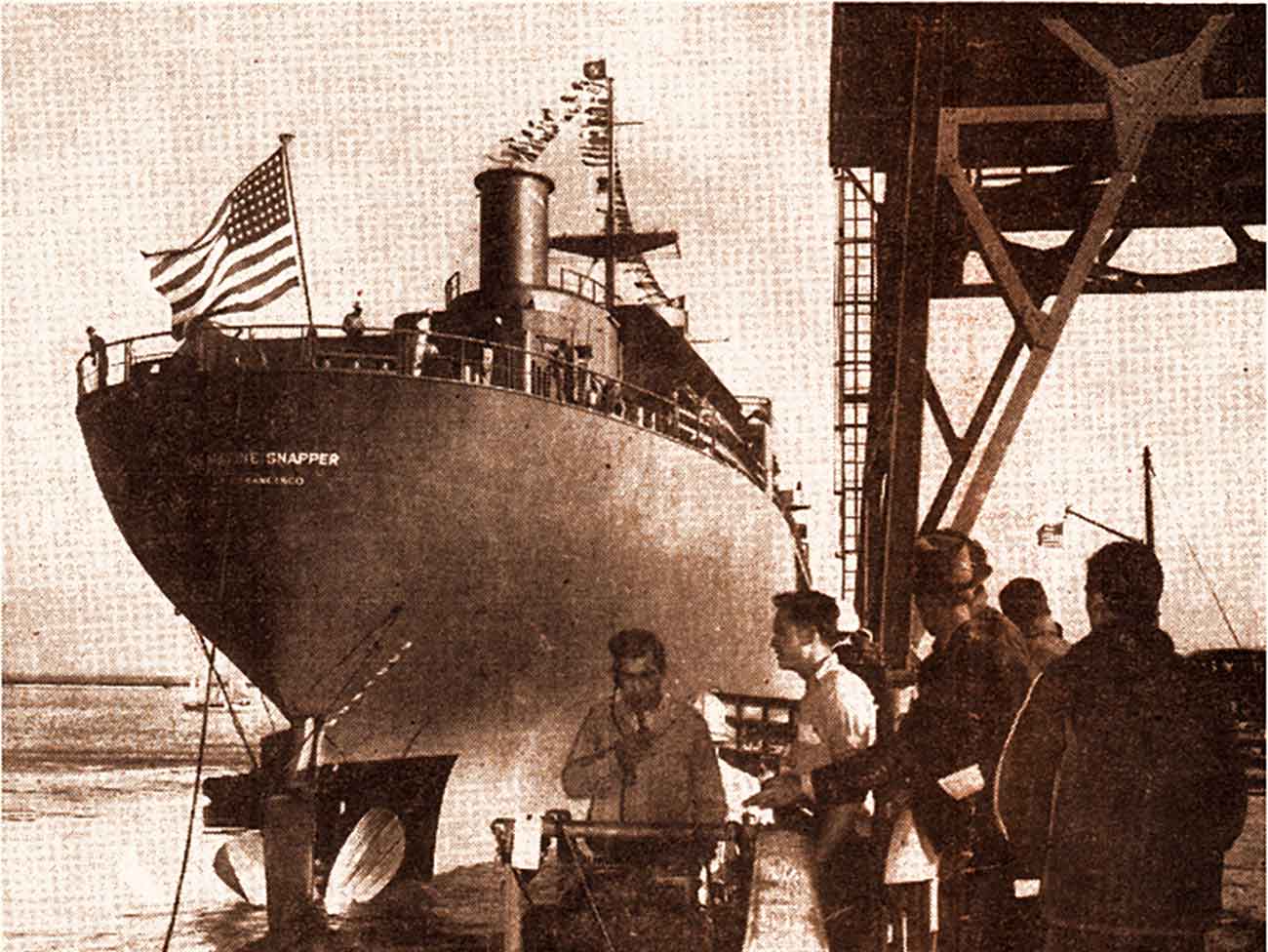

Henry J. Kaiser stands atop a ship in 1942 overlooking the shipyards in Richmond, California.

Henry John Kaiser was a titan of American industry and health care innovation.

His construction legacy spanned from roads to large projects like the Grand Coulee Dam and shipyards. As co-founder of Kaiser Permanente, he influenced a reshaping of 20th-century health care.

Kaiser’s support of an innovative care model is core to Kaiser Permanente’s industry-leading value-based care and coverage today.

Family life

Kaiser was born on May 9, 1882, in Sprout Brook, New York, to parents from Steinheim, Germany. At the time of his birth, his father was a farmer, and his mother was a nurse.

As a boy, Kaiser was sociable and outgoing. His family moved to Whitesboro, New York, in 1899. They lived a few blocks from the Erie Canal. Kaiser and his 3 older sisters enjoyed watching the barges on the waterway near their home.

The 1895 economic depression in the United States prompted 13-year-old Kaiser to find his first job as a salesclerk. His next job was in the photography business. He traveled to large cities around New York selling photography supplies and services.

Kaiser had a close relationship with his mother. When her health worsened in 1899, she gave up being a nurse and stayed home. She died on December 1, 1899, at age 52.

1900 to 1914

Kaiser moves west

After his mother’s death, Kaiser left home and traveled to Lake Placid, New York. He worked at W.W. Brownell photography studio. With his previous experience, he became the owner of the studio by the end of the year.

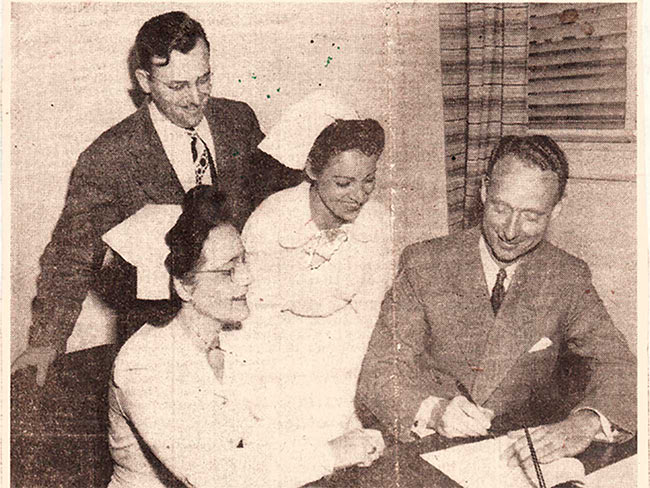

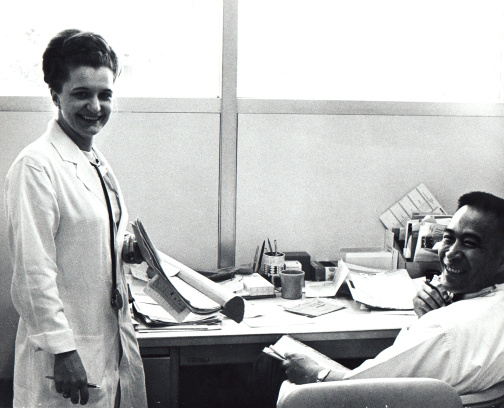

Bess Fosburgh Kaiser with her husband, Henry J. Kaiser, at the first Kaiser Foundation School of Nursing graduation ceremony in 1950

Kaiser met Bess Fosburgh in 1906 when she visited Lake Placid. Her father learned about Kaiser’s humble roots. He asked Kaiser to “go west” where there were construction opportunities and establish himself before marrying Bess.

Such requests were common then, and Kaiser wasn’t offended. He left for Spokane, Washington, and found himself in sales again.

He spent the year quickly growing the business and connecting with leaders. Kaiser became the manager of a regional hardware business.

On April 8, 1907, Henry and Fosburgh married. Their first son, Edgar Fosburgh Kaiser, was born later that year.

Kaiser started working for the J.F. Hill Company in 1912. The company introduced Kaiser to construction and road paving. Unfortunately, Kaiser was fired after a year due to internal company struggles.

Company leaders let him know he was fired while he was dozens of miles from home on a construction job. He decided to finish the job anyway. His peers respected his decision, and Kaiser learned the importance of not leaving a job unfinished.

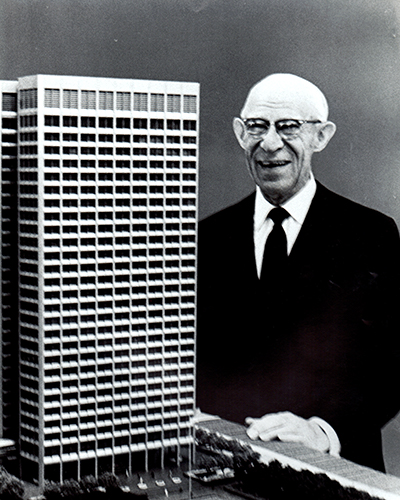

Alonzo B. Ordway is seen here posing next to a scale model of the Ordway Building in Oakland, California.

Alonzo B. Ordway posing next to a scale model of the Ordway Building in Oakland, CA

After returning home, Kaiser planned on opening his first company to pave roads. During his time with the J.F. Hill Company, Kaiser built a strong relationship with a rising young construction supervisor, Alonzo B. Ordway. Kaiser hired “Ord” and some of the best employees from the J.F. Hill Company.

This would be Kaiser’s first company, and he needed a bank loan. Many years later, Kaiser told the story about having no collateral to offer the bank manager except his 20-hour-per-day work ethic, experience, and enthusiasm.

Despite the liability, the bank manager granted Kaiser the loan. In 1914, he established the Henry J. Kaiser Company, Ltd.

1915 to 1930

Kaiser learns the value of labor-management partnerships

With his first company established, Kaiser and his team set off to bid on their first construction job in Redding, California.

They misread the train routes and discovered that there were no stops in Redding. They waited till the train slowed down near their destination and jumped off. The team won its first bid.

Early road construction used horse-drawn scrapers, wide shovel-like sheets used to move dirt. Kaiser and his team created tractor-drawn road scrapers. They finished a weeklong job in days.

Looking back, Kaiser recalled the value of working with his employees to improve efficiency.

A view of Henry J. Kaiser Company steamrollers preparing the roadbed in Camaguey, Cuba, 1927

Kaiser Paving Company Cuban Central Highway construction

In 1927, Kaiser’s team won a new contract to build 200 miles of road and 500 bridges in Cuba. The completed contract would be part of the Central Highway in Cuba.

Early in the project, the construction machines kept failing. Kaiser’s team had to rely on Cuban workers to do the work manually as the machines were repaired.

The team learned that the workers did the tasks better and faster than the machines. They finished the job 3 years ahead of schedule in 1930.

Kaiser and his team left Cuba with lifelong lessons about the power of people and the value of having strong relationships with a workforce.

1930 to 1939

Grand Coulee Dam

The 1930s in the United States were defined by the worldwide economic downturn known as the Great Depression. But it was also a period of large American dam construction projects.

Kaiser was elected the chairman of a joint venture combining 6 major construction companies. Called the Six Companies, Inc., their first job was building Hoover Dam. Through innovating efficient construction methods, the job was finished in 5 years instead of 7.

The company’s next jobs were the Bonneville and Grand Coulee dams on the Columbia River.

Kaiser’s attention turned to the lack of adequate health care at Grand Coulee Dam. Workers were receiving expensive and inadequate care by existing doctors. When Ordway heard about the lack of health care, he told Kaiser about a young doctor he met years earlier: Sidney R. Garfield, MD.

Dr. Garfield provided care to construction workers building the Colorado River Aqueduct. He operated the only hospital within hundreds of miles. In a time of financial need, he used the process of prepayment to finance the hospital. Workers prepaid each week to cover all health care costs. He promoted prevention of injuries and illness by educating workers about safety.

Ordway invited Dr. Garfield to visit the Grand Coulee worksite. After assessing the situation, Kaiser and Dr. Garfield agreed to a partnership to start a new health plan. The Grand Coulee Dam project led to the first partnership between Kaiser and Dr. Garfield.

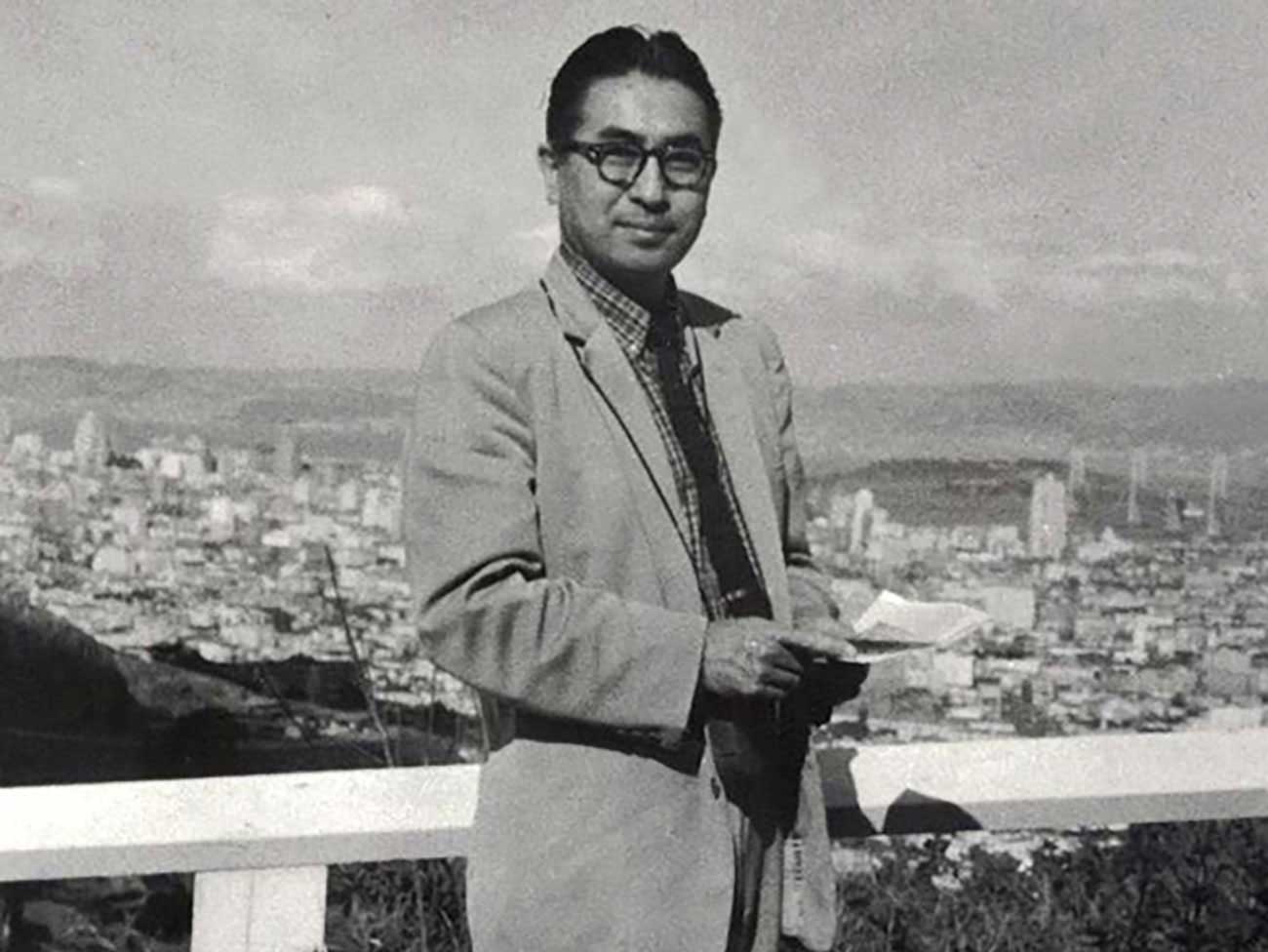

Dr. Garfield sits in front of Contractors General Hospital in 1935. His ideas of prepayment and preventive care laid the foundation for Kaiser Permanente’s future health plan.

The health plan they introduced allowed workers to prepay a small cost each week. In exchange, workers and their families received health care at no extra cost during visits. This promoted people to seek care early, preventing common and serious illnesses.

1940 to 1945

Kaiser’s shipyards and the home front’s health plan

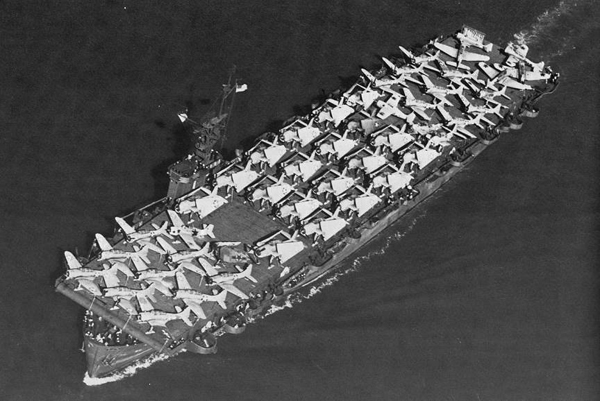

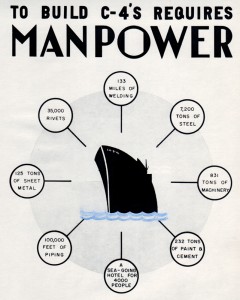

In 1940, the U.S. began building cargo ships for British allies fighting in World War II. Kaiser decided to help by building and operating shipyards.

Kaiser had never built ships before, and competitors doubted him. But he was a quick learner.

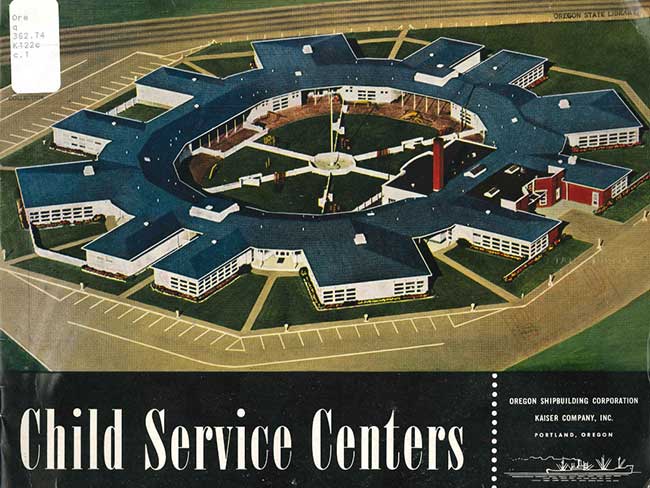

His team quickly built shipyards in Richmond, California; Portland, Oregon; and Vancouver, Washington. When America entered World War II in 1941, Kaiser’s shipyards were already in operation.

![Henry J. Kaiser and Richmond shipyard workers, 1942 [circa]](/content/dam/kp/mykp/images/photos/people/HJK-and-Richmond-shipyard-workers-1942.jpg)

Kaiser (center top, wearing glasses) meets with workers in Richmond, California, in 1942 to congratulate them on jobs well done.

By the end of 1942, Kaiser’s shipyards employed 80,000 workers. They came from all over the nation. The Kaiser shipyards reached their peak in 1944 with more than 200,000 workers.

Kaiser’s yards operated around the clock. Men and women of all races, ethnicities, and abilities worked as peers. Thousands of diverse workers arrived from all over the country.

Many people who did not pass the military health requirements joined the shipyards. They arrived with little or no previous health care and were getting sick. Kaiser realized they needed care. He called Dr. Garfield and asked him to set up a shipyard health plan. Kaiser wanted it to be like the one they had offered to workers building the Grand Coulee Dam.

Dr. Garfield and a group of doctors offered the health plan at all of Kaiser’s shipyards. It was called the Permanente Health Plan.

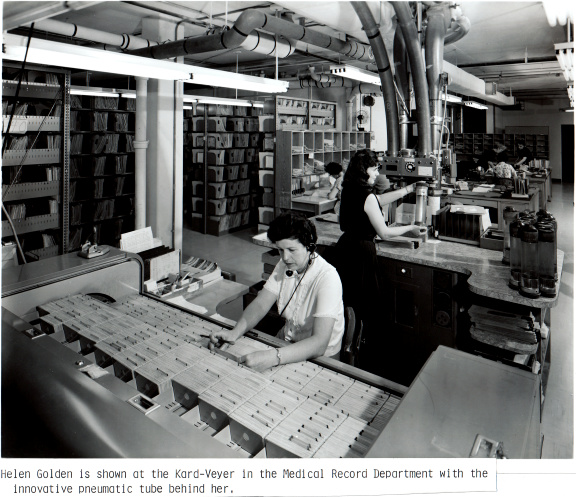

Like at the Grand Coulee Dam, health plan members prepaid a small weekly cost. In exchange, they received care for common illnesses and injuries. They also received preventive care, such as vaccinations, and health education to help keep them healthy.

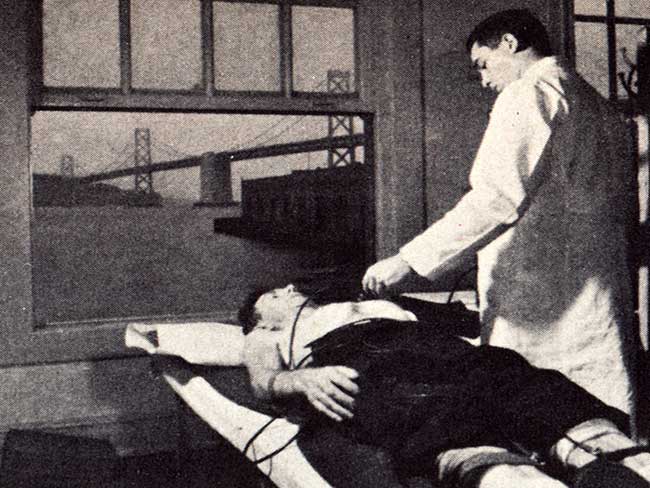

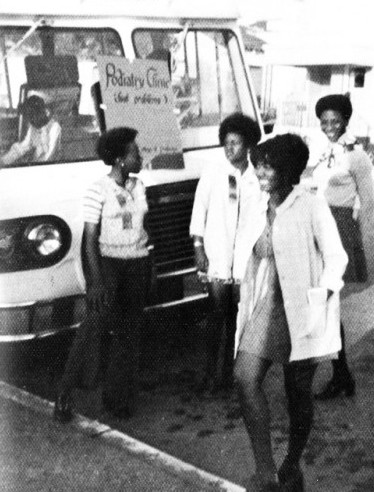

Black patients and white patients receive care at an integrated ward at the Permanente Oakland Hospital in 1942. It was one of the few U.S. hospitals at the time with racially integrated wards.

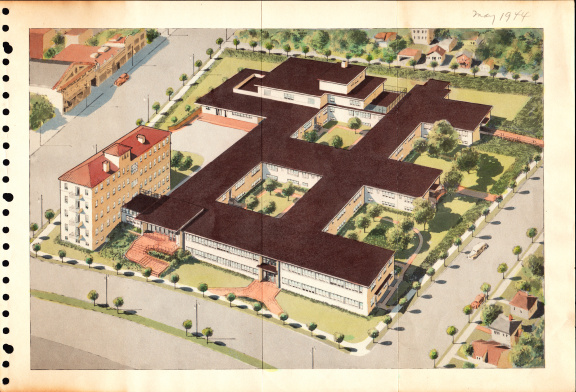

To support the health plan, Kaiser’s construction teams renovated the Fabiola Hospital in Oakland, California, with the latest advanced equipment. It was renamed the Permanente Oakland Hospital and opened in 1942. First aid stations in the shipyards treated minor injuries. The Permanente Field Hospital in Richmond treated more serious cases. For severe injuries and illnesses, ambulances took patients to the new Permanente Oakland Hospital.

More than 200,000 people (workers and their family members) were members of the Permanente Health Plan.

Doctors working in traditional care models saw the new health plan model as a threat. The plan challenged old forms of health care that relied on the real-time exchange of money for services.

1945 to 1967

A new health plan for Americans

As the war wound down in 1945, demand for ships slowed. Kaiser’s shipyards began closing. Workers and their families returned home. Health plan membership dropped.

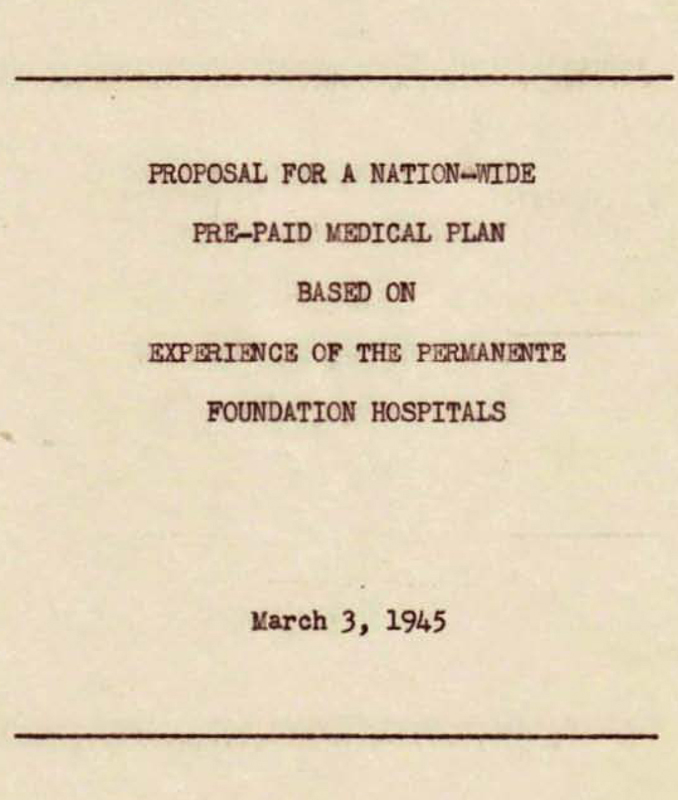

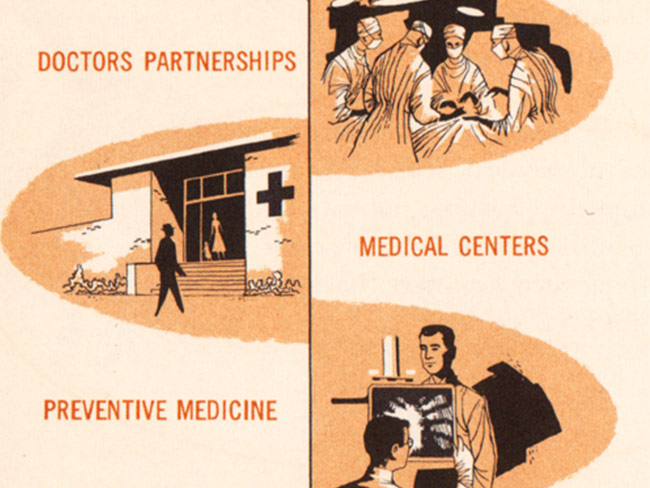

And yet Kaiser and Dr. Garfield saw in their shipyard health plan a new vision for health care in America.

They wanted to continue delivering care in this new way — using prepayment, group practice, and a focus on injury and illness prevention.

Together, Kaiser and Dr. Garfield opened the Permanente Health Plan to the public on July 21, 1945.

Soon after, Kaiser and his wife set up the Kaiser Family Foundation, a charitable trust.

The foundation opened the Kaiser Foundation School of Nursing in 1947. Enrollment was open to all, regardless of race and background. Students received room and board and a tuition-free education.

(Kaiser Family Foundation is no longer associated with Kaiser Permanente, the Kaiser Foundation School of Nursing, or Kaiser Industries.)

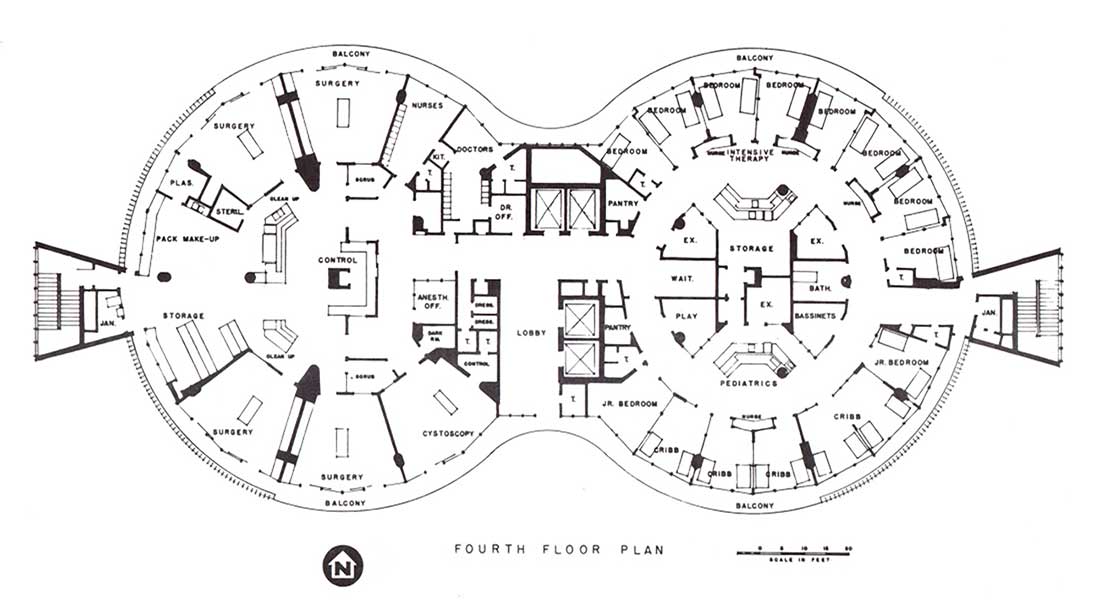

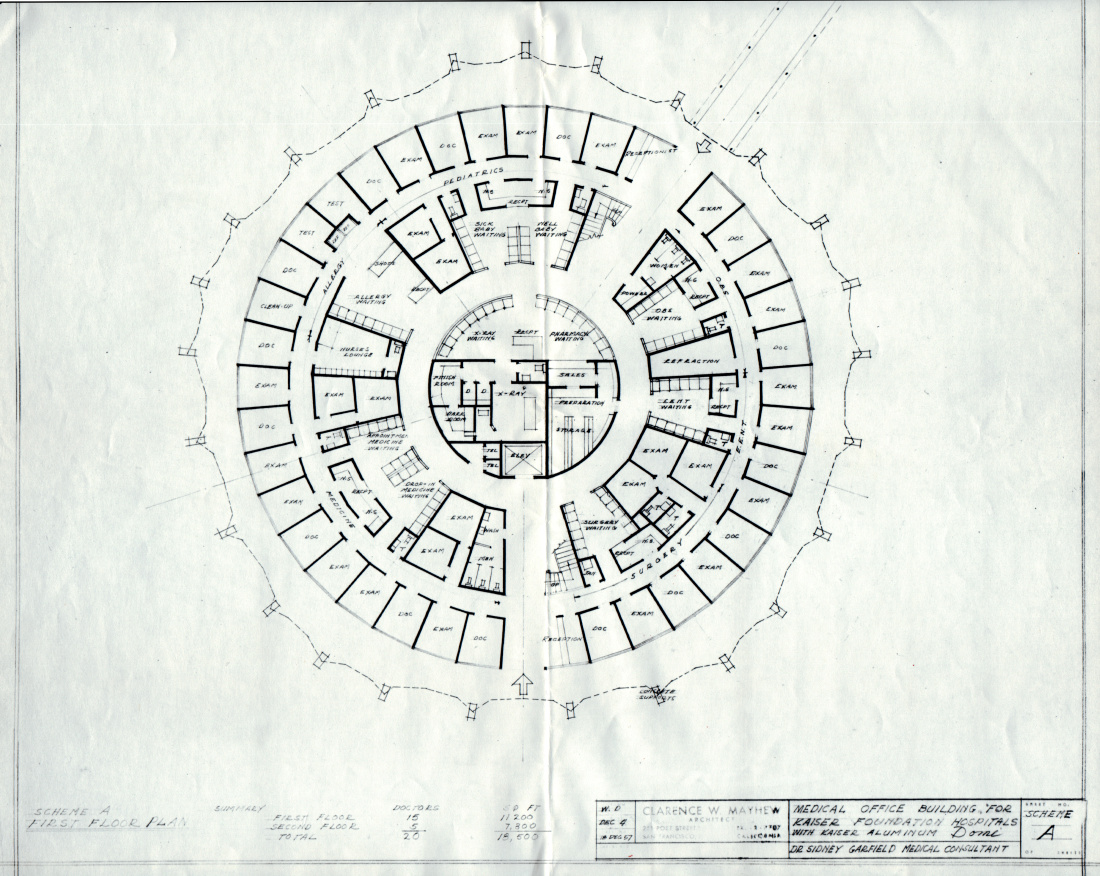

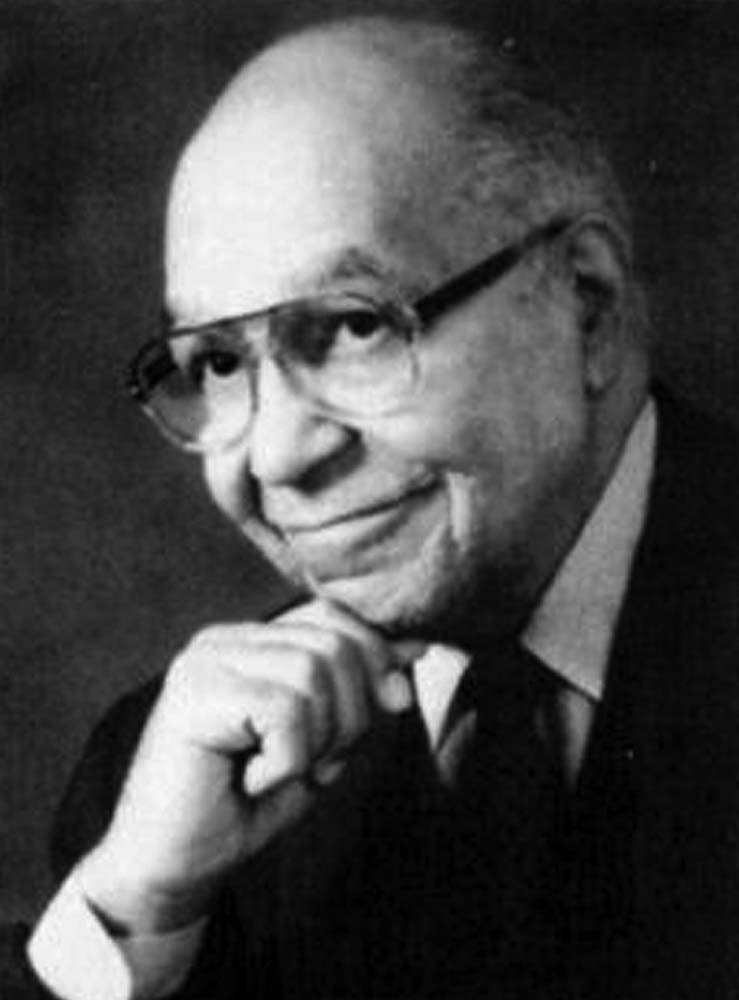

Kaiser and Dr. Garfield review hospital plans in 1953. On the table is a model of the innovative Walnut Creek Hospital, which featured bedside push-button consoles for patients and an advanced surgical suite.

1946 to 1967

Kaiser's legacy

After World War II, Kaiser’s ongoing partnership with Dr. Garfield led to new hospitals. The Permanente Health Plan was renamed Kaiser Permanente. Kaiser also launched other businesses in automobile, aircraft, radio, and television.

“Of all the things I’ve done, I expect only to be remembered for my hospitals. They’re the things that are filling the people’s greatest need: good health,” said Kaiser, decades before his death.

Kaiser died August 27, 1967. Leading up to his death, Kaiser continued planning new projects and focusing on the future.