Kaiser Permanente's early support from labor

Experiencing the Kaiser Permanente health plan led labor unions to support and promote the health plan after World War II for accessible and preventive care.

Nurses Guild Local 699 (CIO), signing first Permanente Foundation hospital nurses contract. Labor Herald, August 23, 1946.

From providing health care to workers and their families at Grand Coulee Dam to the massive medical program in the World War II shipyards, Henry J. Kaiser believed that cooperating with labor was more productive than fighting it. This institutional philosophy had profound positive implications for the nascent public postwar health plan. As the war was drawing to a victorious close — Victory in Europe had been announced on May 8, 1945 — Henry J. Kaiser’s health plan began to prepare for a peacetime economy by expanding beyond its own employees. The plan would be opened to the public by late July.

Given Henry J. Kaiser’s support for labor, it was not surprising that labor unions would be among the early member groups. Bay Area workers — Oakland city employees, union typographers, streetcar drivers, and carpenters — embraced the Permanente Health Plan and its emphasis on preventive medicine.

On June 7, 1945, the Stewards and Executive Council of the International Longshoremen and Warehousemen Union’s Oakland unit voted unanimously to make coverage in Permanente a part of its future negotiations with employers. The executive council also requested that employers pay for the plan’s premiums.

Founding physician Sidney Garfield, MD., reflected on that support:

"So [the postwar health plan] gathered momentum… [In 1949] the longshoremen's union came to us and said, "We would like you to take over all our members." They had about thirty thousand here and the [San Francisco] Bay area. They said, "We won't give them to you unless you do it up in Portland, Seattle, Los Angeles, and San Diego. We want to give you the whole thing.

"Then Joe DeSilva of the Retail Clerks' union called up and wanted to see me. He came up here and said, "I want you to set up a health plan for our workers in Los Angeles." I guess he had about thirty thousand workers plus families of I don't know how many. I told him that we would need facilities because we couldn't depend on using other hospitals because someday they would boycott us probably. So he said, "I'll pay you several month's dues in advance if that will help you build a hospital."1

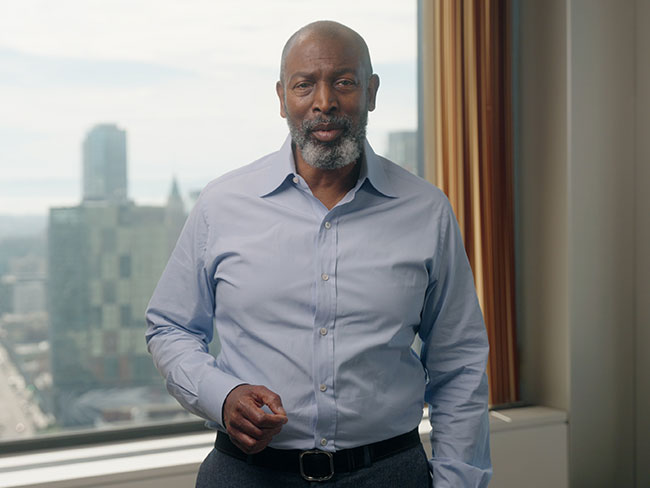

Years later, Kaiser Permanente CEO David Lawrence would express that relationship succinctly:

“If not for organized labor’s active marketing support immediately following World War II, it is unlikely that Kaiser Permanente would exist today.”2

But labor did not just mean health plan members, labor employees were also a key part of delivering health care. A year after opening up to the public, the Permanente Health Plan signed its first nurses' contract with the hospital in Oakland and the field hospital in Richmond, making it the first nurses’ union in the U.S. to do so.

On July 26, 1946, the Nurses Guild Local 699, affiliated with the Congress of Industrial Organizations, announced that they approved a contract covering wages and working conditions with Permanente Hospital of Oakland and Richmond (as well as medical staff at Kaiser Steel in Fontana). Lora Lee Swan, nurse consultant for the Guild, declared:

"This is the first Alameda County hospital in which nurses have been allowed their democratic rights to a free election in choosing their bargaining agent. The precedent set here is truly a great victory for working nurses everywhere." 3

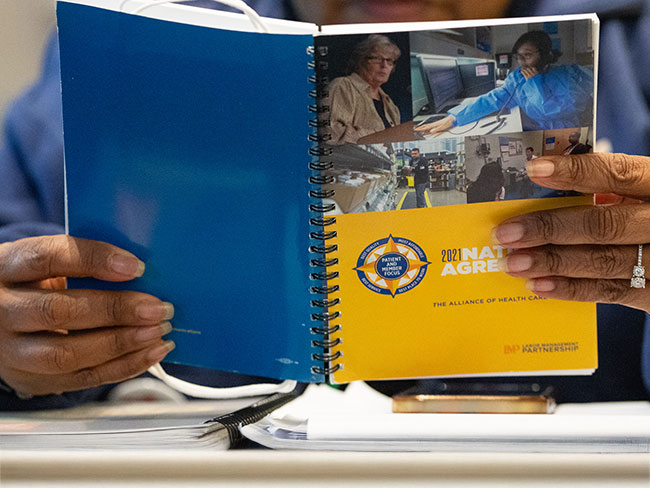

In 1997, after years of labor turmoil within Kaiser Permanente and competitive pressures within the health care industry, Kaiser Permanente and the Coalition of Kaiser Permanente Unions formed their groundbreaking Labor Management Partnership. Today, the partnership covers more than 100,000 union-represented employees in 28 local unions as well as 14,000 managers and 17,000 physicians in California, Washington, Oregon, Colorado, Georgia, Hawaii, Virginia, Maryland, and Washington, D.C.

1 “Pre-paid Medicine: Kaiser Hospital in Oakland is Opened to the Public,” S.F. Chronicle, July 21, 1945.

2 “Leaders Tell How — and Why — Health Plan Grew,” KP Reporter, May 1962.

-

Social Share

- Share Kaiser Permanente's early support from labor on Pinterest

- Share Kaiser Permanente's early support from labor on LinkedIn

- Share Kaiser Permanente's early support from labor on Twitter

- Share Kaiser Permanente's early support from labor on Facebook

- Print Kaiser Permanente's early support from labor

- Email Kaiser Permanente's early support from labor

March 4, 2026

Kaiser Permanente again presents a comprehensive proposal

Negotiations are at a turning point.

February 27, 2026

Important progress made in Alliance local bargaining

UNAC/UHCP accepts our 21.5% across-the-board wage offer as local bargaining …

February 23, 2026

UNAC/UHCP to end strikes in California and Hawaii markets

Kaiser Permanente employees will return to their normal schedules in a …

February 6, 2026

Update on Alliance local bargaining

Kaiser Permanente provides comprehensive contract proposals to each of …

February 4, 2026

It's not fuzzy. It's basic math.

You deserve your raises now, and Kaiser Permanente is ready to deliver …

January 31, 2026

For us, it's all about our people

Understanding the facts of UNAC/UHCP’s demand for nursing pay hikes of …

January 28, 2026

Bargaining continues in 25th session since July 2025

Kaiser Permanente and NUHW have important conversations about safety.

January 25, 2026

Our statement on the UNAC/UHCP strike

A strike that will disrupt the lives of our patients is unnecessary when …

January 22, 2026

Kaiser Permanente’s statement on the best way forward in Alliance bargaining

Local bargaining tables are the most effective path to secure new contracts …

January 21, 2026

First session in 2026 aimed at forward momentum and progress

Kaiser Permanente and NUHW met for the 24th time since bargaining began …

January 21, 2026

Know the facts about the shift to local bargaining

On January 21, Kaiser Permanente communicated that all open bargaining …

January 21, 2026

Moving forward

Local bargaining is the right path to delivering wage increases and enhanced …

January 16, 2026

Kaiser Permanente’s statement on latest strike notice by UNAC/UHCP

Despite a way forward in bargaining offered by Kaiser Permanente, union …

January 15, 2026

Kaiser Permanente’s statement on a path forward in Alliance bargaining

Our solution puts the interests of our employees up front and upholds our …

January 15, 2026

A path forward for Alliance bargaining

We’re putting your interests up front and upholding our Labor Management …

January 9, 2026

Where we are, and ways forward

Although national bargaining remains paused, we’ve made progress in local …

December 26, 2025

Momentum at local tables

Here are the facts about progress at local bargaining.

December 18, 2025

Why we paused bargaining

We made the difficult decision to pause national bargaining with the Alliance …

December 17, 2025

Final session of 2025 concludes with one tentative agreement

Four additional bargaining dates set to kick off the new year.

December 14, 2025

Let’s close the deal

Historic 21.5% wage boost and enhanced benefits await. Watch this message …

December 10, 2025

A productive 22nd NUHW bargaining session

After a 3-week hiatus, 3 tentative agreements were reached.

December 5, 2025

Where we stand

New bargaining dates are set for December 11 to 15, as Alliance-represented …

November 20, 2025

It’s time to move forward

Our strong, historic offer honors Alliance-represented employees’ contributions …

November 18, 2025

Busy day at the bargaining table for Kaiser Permanente and NUHW

Several responses to proposals were shared in 21st bargaining session.

November 11, 2025

Kaiser Permanente and NUHW check in on outstanding proposals

Three responses were shared in the 20th bargaining session.

November 7, 2025

Kaiser Permanente and NUHW reach one tentative agreement

Additional sessions in December were confirmed.

November 7, 2025

Negotiations continue

Kaiser Permanente offers proposal that would provide for more employee …

November 4, 2025

Visualizing our offer

New online tool provides Alliance-represented employees a personalized …

October 31, 2025

Kaiser Permanente and NUHW continue negotiations

Four proposals were exchanged in 18th bargaining session.

October 28, 2025

2 tentative agreements reached in 17th session

Kaiser Permanente and NUHW continue making progress at the bargaining table.

October 24, 2025

Strong offer, stronger future

Kaiser Permanente’s economic proposal rewards Alliance-represented employees …

October 19, 2025

Kaiser Permanente returns to normal operations after strike

Bargaining for a new national contract with the Alliance of Health Care …

October 16, 2025

Bargaining continues during 16th session

Additional counterproposals exchanged between Kaiser Permanente and NUHW.

October 13, 2025

Our statement on the Alliance of Health Care Unions’ strike

We remain committed to an agreement that balances fair pay with affordable …

October 12, 2025

A strong offer that puts patients and employees first

We're committed to reaching an agreement that honors our employees, protects …

October 11, 2025

Another tentative agreement reached in bargaining

Additional counterproposals exchanged between Kaiser Permanente and NUHW.

October 10, 2025

Latest bargaining session fails to reach agreement

We are committed to negotiating a fair contract with the Alliance, despite …

October 6, 2025

Kaiser Permanente and NUHW exchange multiple proposals

Session marked by continued dialogue.

October 4, 2025

Despite strong offer on the table, strike notices received

Kaiser Permanente strengthens latest economic proposal offering competitive …

October 2, 2025

Key proposals reintroduced at NUHW bargaining

Kaiser Permanente and NUHW reach a tentative agreement on associate licensure …

September 30, 2025

Tailoring mental health care to the needs of our members

Recognizing that mental health is an essential part of overall well-being, …

September 29, 2025

Work continues to reach new national agreement

Kaiser Permanente and Alliance enter into third-party mediation to help …

September 26, 2025

Bargaining continues with meaningful exchange of proposals

Kaiser Permanente and the National Union of Healthcare Workers exchange …

September 24, 2025

Bargaining gains momentum with 2 new tentative agreements

Kaiser Permanente and the National Union of Healthcare Workers agree on …

September 24, 2025

A job at Kaiser Permanente is much more than a paycheck

Being a part of the country’s largest mission-driven health care organization …

September 24, 2025

See what makes our offer stand out

Higher pay and investments in your benefits and educational opportunities …

September 22, 2025

NUHW bargaining sessions provide robust exchanges

Kaiser Permanente and the National Union of Healthcare Workers discuss …

September 19, 2025

Understanding the value of a Kaiser Permanente job

Our proposal means higher pay and stronger benefits for you.

September 17, 2025

Progress continues in NUHW bargaining sessions

Kaiser Permanente and the National Union of Healthcare Workers exchange …

September 13, 2025

The value of a Kaiser Permanente job

Kaiser Permanente is proud to offer competitive pay, outstanding benefits, …

September 13, 2025

Update on Alliance national bargaining

Negotiations focus on pay, benefits, and remaining staffing proposals.

September 13, 2025

Details of our latest offer to the Alliance of Health Care Unions

Kaiser Permanente rewards employees for the excellent care they provide.

August 29, 2025

Negotiations focus on patient access, therapist support

Kaiser Permanente and NUHW continue to exchange and consider proposals.

August 28, 2025

We celebrate our employees this Labor Day

Kaiser Permanente has a long, proud history of working with unions.

August 26, 2025

Kaiser Permanente and NUHW bargaining update

Our proposals to the National Union of Healthcare Workers seek greater …

August 23, 2025

Alliance national bargaining update

New tentative agreements enhance the minimum wage and strengthen the Labor …

August 15, 2025

NUHW bargaining progresses

Discussions at the bargaining table focused on the job duties and workload …

August 13, 2025

Third tentative agreement reached

Kaiser Permanente and the National Union of Healthcare Workers continue …

August 7, 2025

Alliance national bargaining talks move forward

Kaiser Permanente and the Alliance reach 30 tentative agreements.

July 31, 2025

Second tentative agreement reached

Kaiser Permanente and the National Union of Healthcare Workers reached …

July 24, 2025

NUHW bargaining continues in Northern California

Kaiser Permanente and the National Union of Healthcare Workers reached …

July 17, 2025

National bargaining talks progress

Kaiser Permanente and Alliance of Health Care Unions navigate key issues. …

July 17, 2025

2025 Alliance national bargaining facts at a glance

July 11, 2025

NUHW bargaining update in Northern California

In a second bargaining session, Kaiser Permanente and the National Union …

July 8, 2025

NUHW bargaining begins in Northern California

First day of negotiations between Kaiser Permanente and the National Union …

July 8, 2025

Working together at the heart of health care

Organized labor is key to who we are, where we’ve been, and where we’re …

June 23, 2025

How Kaiser Permanente uses AI responsibly

To guide our use of AI, Kaiser Permanente has created a set of 7 responsible …

June 5, 2025

National bargaining progress continues

Kaiser Permanente and Alliance unions reach 4 tentative agreements and …

June 4, 2025

Frequently asked questions about bargaining

Here’s what you should know now that Alliance of Health Care Unions national …

May 8, 2025

New NUHW contract ratified

Kaiser Permanente Southern California and the National Union of Healthcare …

May 8, 2025

Interest-based problem solving: What it is, why it matters

During national bargaining, labor and management use this collaborative …

May 8, 2025

National Alliance bargaining begins

Kaiser Permanente and the Alliance of Health Care Unions kick off negotiations …

April 30, 2025

A history of trailblazing nurses

Nursing pioneers lay the foundation for the future of Kaiser Permanente …

April 16, 2025

Sidney R. Garfield, MD: Pioneer of modern health care

Kaiser Permanente’s co-founding physician spread prepaid care and the idea …

May 3, 2024

Henry J. Kaiser: America’s health care visionary

Kaiser was a major figure in the construction, engineering, and shipbuilding …

April 8, 2024

Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream is alive at Kaiser Permanente

Greg A. Adams, chair and chief executive officer of Kaiser Permanente, …

February 13, 2024

A legacy of life-changing community support and partnership

The Kaiser Permanente Watts Counseling and Learning Center started as a …

February 2, 2024

Expanding medical, social, and educational services in Watts

Kaiser Permanente opens medical offices and a new home for the Watts Counseling …

November 9, 2023

New 4-year agreement ratified

National agreement between Kaiser Permanente and the Coalition will help …

October 17, 2023

How Kaiser Permanente evolved

Sidney R. Garfield, MD, and Henry J. Kaiser came together to pioneer an …

September 13, 2023

Transforming the medical record

Kaiser Permanente’s adoption of disruptive technology in the 1970s sparked …

July 26, 2023

Kaiser Permanente hiring 10,000 new staff for Coalition jobs

More than 6,500 of these union-represented positions have already been …

May 2, 2023

Women lead an industrial revolution at the Kaiser Shipyards

Early women workers at the Kaiser shipyards diversified home front World …

April 25, 2023

Hannah Peters, MD, provides essential care to ‘Rosies’

When thousands of women industrial workers, often called “Rosies,” joined …

November 11, 2022

A history of leading the way

For over 75 innovative years, we have delivered high-quality and affordable …

November 11, 2022

Pioneers and groundbreakers

Learn about the trailblazers from Kaiser Permanente who shaped our legacy …

November 11, 2022

Our integrated care model

We’re different than other health plans, and that’s how we think health …

November 11, 2022

Our history

Kaiser Permanente’s groundbreaking integrated care model has evolved through …

October 21, 2022

Kaiser Permanente therapists ratify new contract

New 4-year agreement with NUHW will enable greater collaboration aimed …

October 14, 2022

Contact Heritage Resources

October 1, 2022

Innovation and research

Learn about our rich legacy of scientific research that spurred revolutionary …

May 26, 2022

Nurse practitioners: Historical advances in nursing

A doctor shortage in the late 1960s and an innovative partnership helped …

March 22, 2022

NUHW psych-social employees ratify agreement

The agreement between Kaiser Permanente and the NUHW in Southern California …

September 10, 2021

‘Baby in the drawer’ helped turn the tide for breastfeeding

This innovation in rooming-in allowed newborns to stay close to mothers …

August 25, 2021

Kaiser Permanente’s history of nondiscrimination

Our principles of diversity and our inclusive care began during World War …

July 22, 2021

A long history of equity for workers with disabilities

In Henry J. Kaiser’s shipyards, workers were judged by their abilities, …

June 2, 2021

Path to employment: Black workers in Kaiser shipyards

Kaiser Permanente, Henry J. Kaiser’s sole remaining institutional legacy, …

February 22, 2021

The Permanente Richmond Field Hospital

Forlorn and all but forgotten, it played a proud role during the World …

September 28, 2020

A legacy of disruptive innovation

Proceeds from a new book detailing the history of the Kaiser Foundation …

August 26, 2020

Kaiser Permanente’s pioneering nurse-midwives

The 1970s nurse-midwife movement transformed delivery practices.