Women lead an industrial revolution at the Kaiser Shipyards

Early women workers at the Kaiser shipyards diversified home front World War II defense industries and the American workforce.

Mary Carroll accepts the Merit flag from Rear Admiral Howard L. Vickery on July 19, 1942.

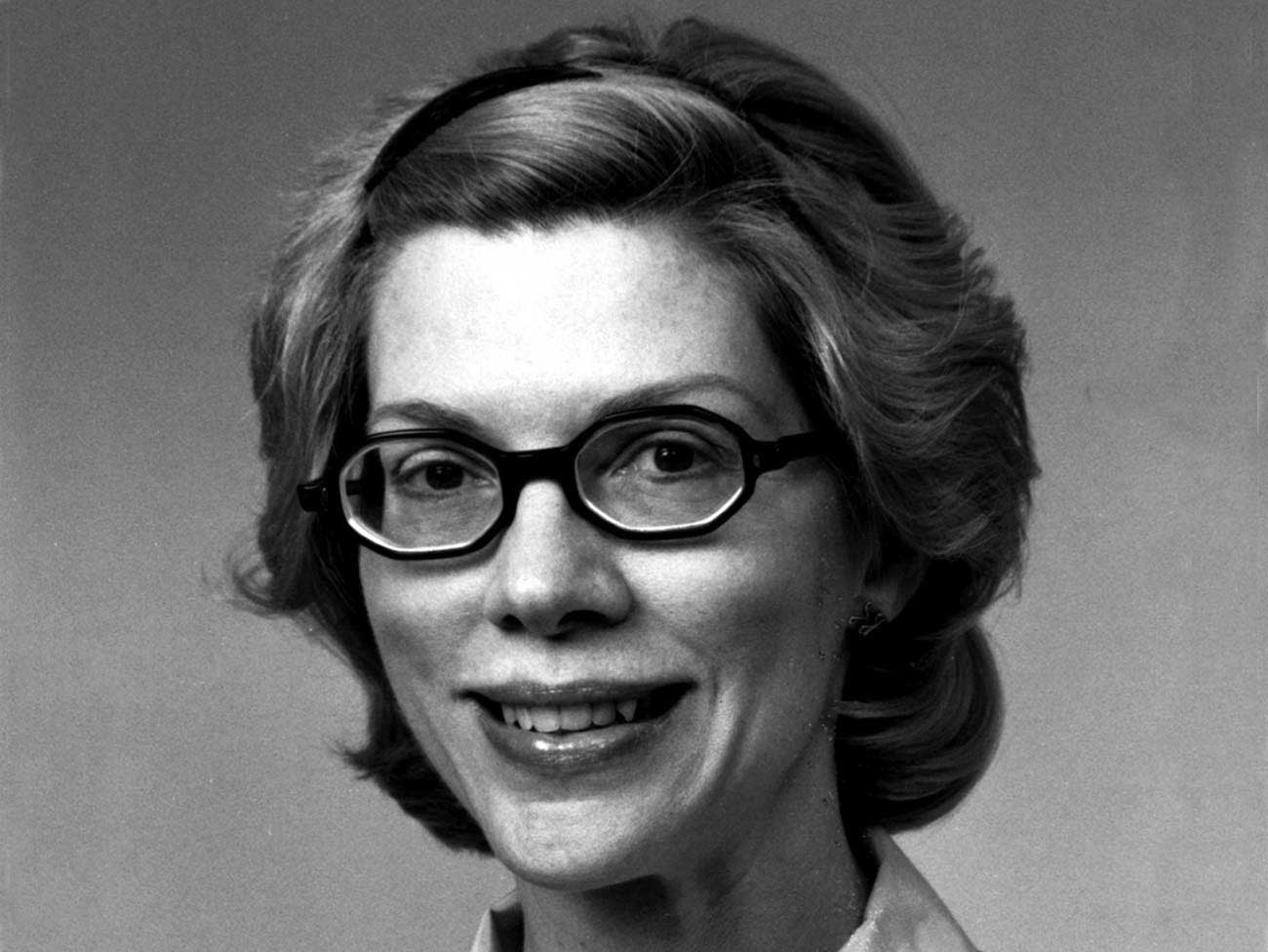

In April 1942, Mary Carroll, Jeanne Wilde, and Louise Cox arrived for their first day at the Kaiser shipyards. They were the first of a new generation of American women doing history-changing work during World War II.

The groundbreakers

Carroll and Wilde started working together at the Kaiser Oregon Shipbuilding Corporation in Portland, Oregon. Wilde and her daughter shared a home with Carroll and her family in the foothills of Lake Oswego near Portland.

Carroll was inspired to join the home front after losing her 27-year-old son in the Battle of Bataan in the Philippines. She is recognized as the first female shipyard welder at the Kaiser shipyards.

On July 19, 1942, Rear Admiral Howard L. Vickery, vice-chairman of the U.S. Maritime Commission, presented the shipyard with the “First Star of the Maritime Burgee” award for speed and efficiency in ship production. Mary Carroll was one of the workers recognized for her excellence.

Jeanne Wilde was a homemaker before joining the home front and becoming a welder.

For Louise Cox, welding was a family affair. She started welding in her family garage, learning acetylene welding from her father when she was a child. At the University of Tennessee, she majored in music and metallurgy. After college, she sang with the San Francisco Opera Company.

Cox took her brother’s place on the production line in Richmond, California, after he joined the Navy. She became the first woman welder trainee at Kaiser Richmond Shipyard No. 2.

When she wasn’t working, Cox designed women’s welding clothes that emphasized safety.

Overcoming challenges and diversifying the workforce

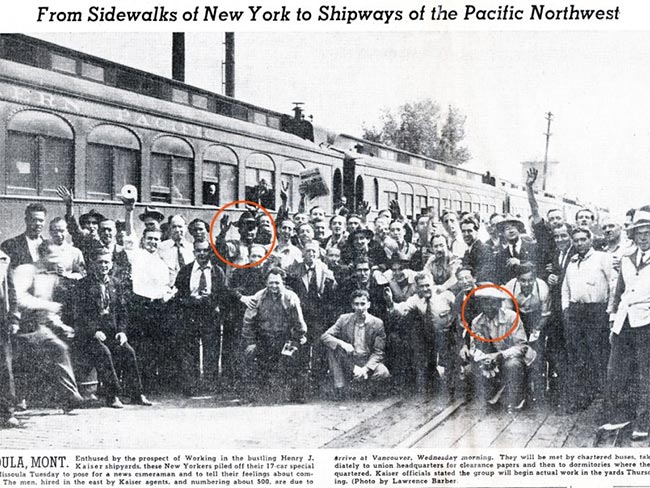

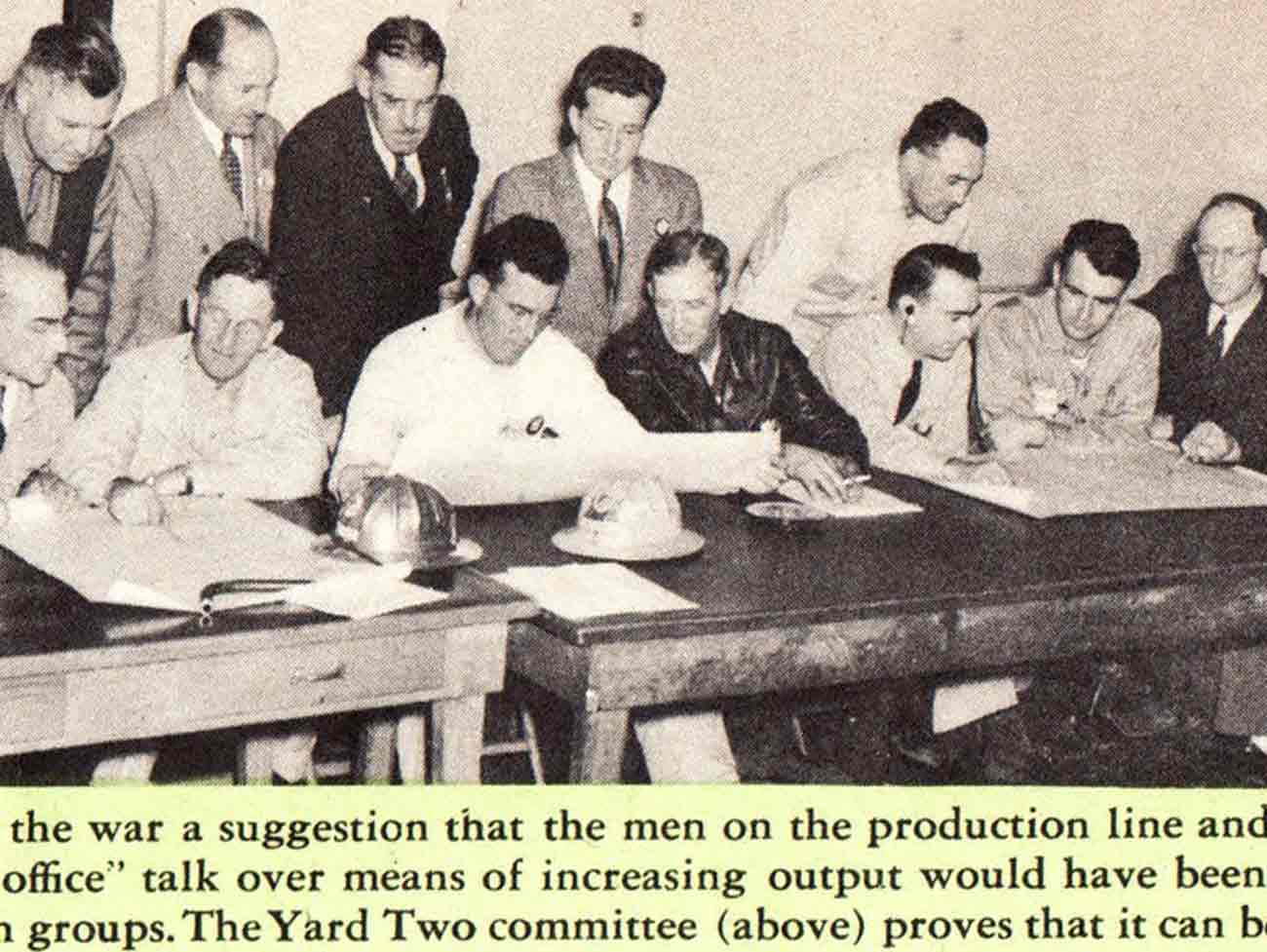

The path to employment at the Kaiser shipyards was not easy for women and Black workers. But Henry J. Kaiser was not your typical industrialist, and his hiring practices made it easier for women and Black people to join the workforce. In 1942 he didn’t hire people through the unions, which were composed of white male workers. To support wartime production, he integrated the shipyards — hiring black men directly and hiring women from the United States Employment Service. Union leaders, of course, voiced their opposition to this strategy.

Kaiser relied on his eldest son, Edgar, to sort out the crisis. Edgar managed to find a temporary solution with the help of the War Manpower Commission. Women hired at the Kaiser shipyards were granted temporary work permit cards pending a vote on admitting them to the International Brotherhood of Boilermakers, Iron Ship Builders, and Helpers of America union.

Boilermakers’ membership voted on a resolution for women’s membership in July 1942. Even though the vote was 12,000 for and 7,000 against, it failed on a quorum technicality.

Tempers flared on both sides of the fight. On September 8, 1942, 22 women welders and burners stormed the Boilermakers union offices in Sausalito, California, to protest not being given union clearance for shipyard jobs. According to an account in the San Francisco Chronicle, the union’s business manager threatened to “yank all women workers out of the shipyards and let the government decide who’s right.”

But the protest got results: 2 days later, top union leaders rewrote the union bylaws, granting official union membership to women.

By March 1943, the Kaiser shipyards employed over 20,000 women. Production hours per ship built dropped from 523,569 to 349,494 between September 1942 and June 1943.

Returning home

Mary Carroll, Jeanne Wilde, and Louise Cox represented the tipping point of a revolution in America. They worked the same jobs as men and received the same pay rate. After the war, America was forever changed when thousands of women returned to civilian life with new jobs, skills, and perspectives.