Wasting nothing: Recycling then and now

Environmentalism was a common practice at the Kaiser shipyards long before Earth Day.

"Ships From the Scrap Heap" Fore 'n' Aft, January 14, 1944

Recycling didn’t start with Earth Day in 1970 — a date that many consider to be the birth date of the modern environmental movement. The reuse of materials has been a practice for many years, especially during shortages of raw materials.

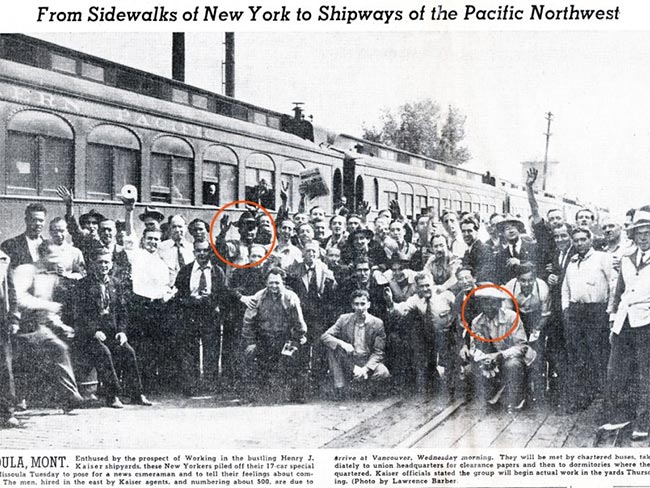

During World War II, the effort to build massive ships also created mountains of industrial trash. And while all resources were prioritized for winning the war against fascism, everyone was encouraged to step up to produce as efficiently as possible. At the Kaiser shipyards, that also meant recycling.

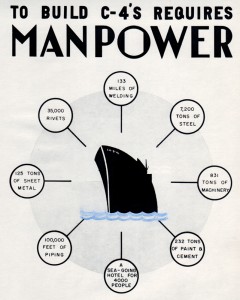

In 1944, the 4 Kaiser shipyards in Richmond, California, produced more than 11,000 gross tons of scrap steel and 78,000 pounds of non-ferrous metals, as well as 11,400 paint pails, 2,056 carbide drums, and large quantities of rubber scrap, wire rope reels, scrap burlap, rope, batteries, and battery plates.

Much of the material collected was recycled on site. “The idea is to waste nothing,” a writer explained in the Kaiser Richmond shipyard newspaper, Fore ‘n’ Aft. “Strongbacks (braces), clips, dogs, wedges, bolts, nuts, and the like are dropped down separate chutes into bins to be reclaimed in the shop.” The article pointed out that at the shipyards’ “Yard Three,” during the previous month, a crew of 137 salvage workers had reclaimed 14,800 feet of pipe, sold 318 tons of scrap pipe-ends, made 254,616 strongbacks and clips, and reclaimed over 176,000 bolts and nuts.

Fast forward to the present and Kaiser Permanente is continuing to stake out ambitious goals for recycling. In fact, the organization aims to recycle, reuse, or compost 100% of its non-hazardous waste by 2025.

Then, as now, recycling on a massive scale requires hard work. At the wartime shipyards, scrap ferrous metals were collected for sending to steel mills for re-melting, but only about 10% were ready to go into the furnaces. The rest had to stop off at preparers for sorting and cleaning. And recycling didn’t stop at the water’s edge. The job of salvage even carried on to the high seas where the ships brought back scrap from the world's battlefields. Aboard ship, cooking fats and tin cans were saved from the galley; flue dust from the boilers and fireboxes yielded strategic vanadium and lamp black; and sailors were encouraged to save every possible rope-end.

“Scramble and scrape to save scrap to scramble the enemy,” the Fore ‘n’ Aft article ends. “Don't forget your part as a war worker handling vital materials is a big one. Make everything count so you can make more things that count. Try to imagine a price tag on every piece of scrap.”

Creating healthy communities by preserving natural resources — good advice then and now.

-

Social Share

- Share Wasting Nothing: Recycling Then and Now on Pinterest

- Share Wasting Nothing: Recycling Then and Now on LinkedIn

- Share Wasting Nothing: Recycling Then and Now on Twitter

- Share Wasting Nothing: Recycling Then and Now on Facebook

- Print Wasting Nothing: Recycling Then and Now

- Email Wasting Nothing: Recycling Then and Now

April 30, 2025

A history of trailblazing nurses

Nursing pioneers lay the foundation for the future of Kaiser Permanente …

April 16, 2025

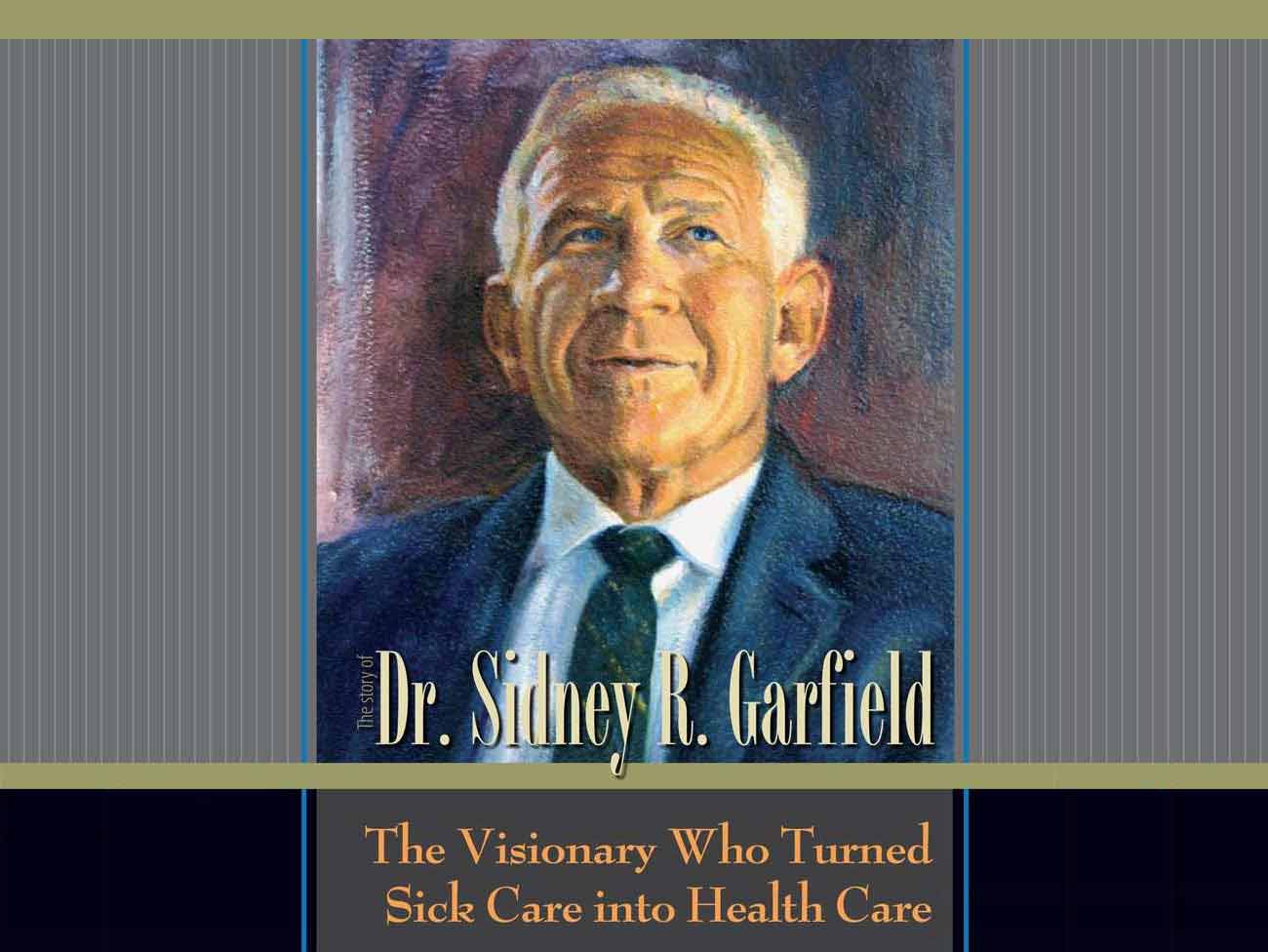

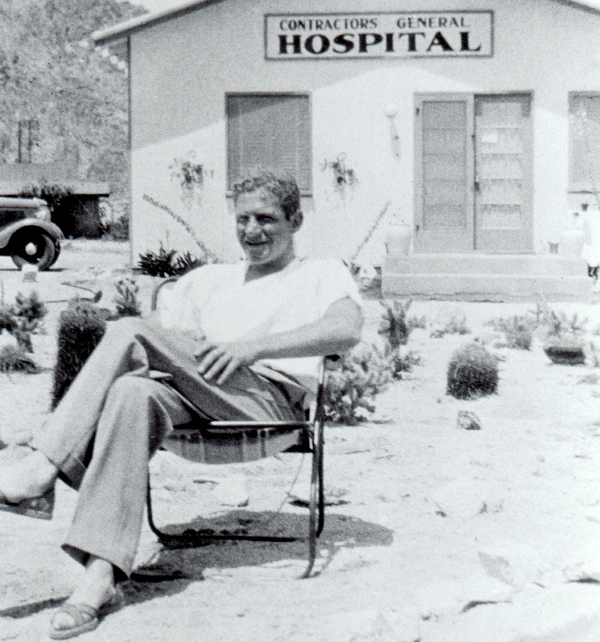

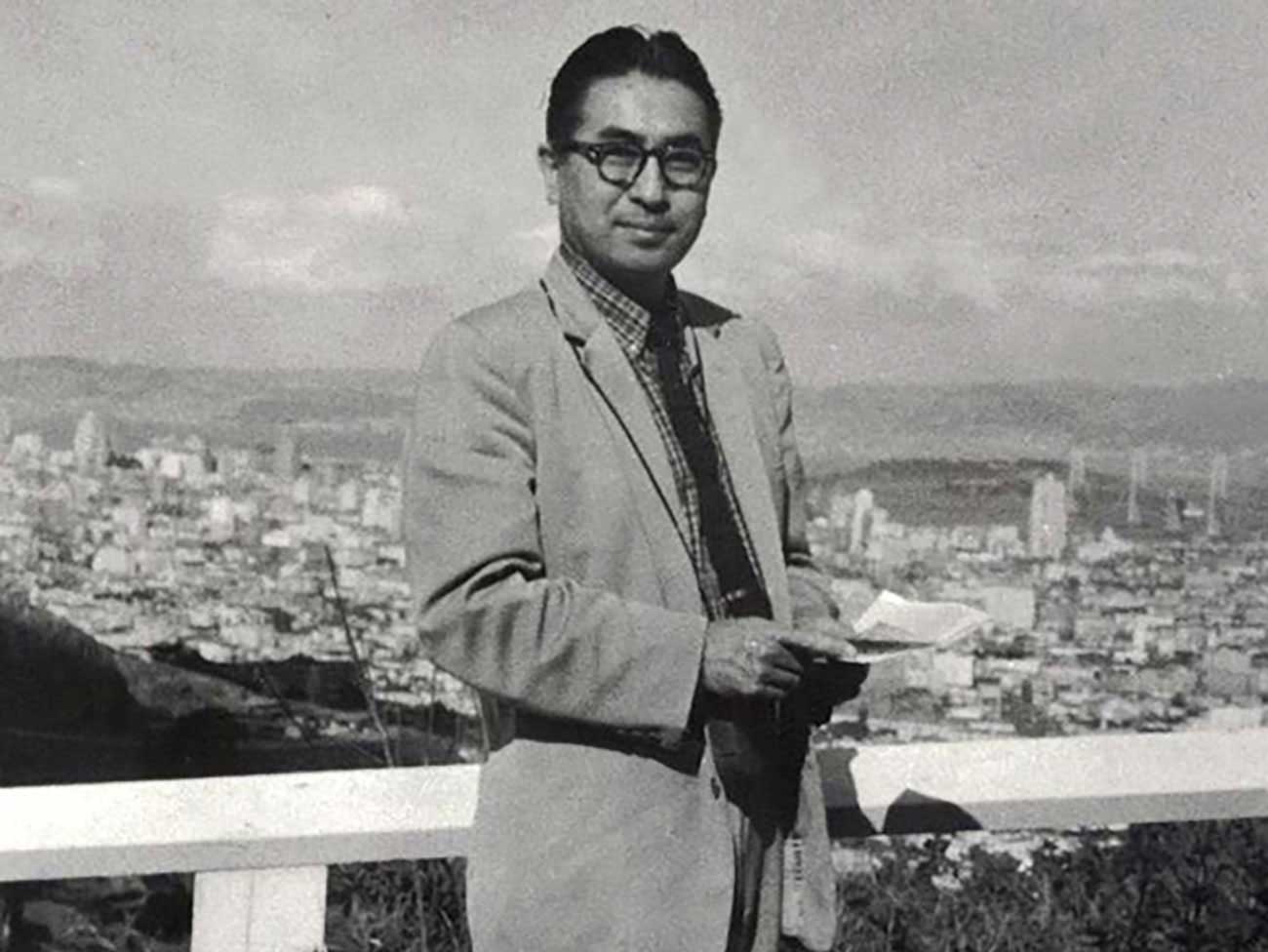

Sidney R. Garfield, MD: Pioneer of modern health care

Kaiser Permanente’s co-founding physician spread prepaid care and the idea …

March 25, 2025

AI in health care: 7 principles of responsible use

These guidelines ensure we use artificial intelligence tools that are safe …

October 16, 2024

Leading in sustainable building design

Kaiser Permanente tops LEED health care facility rankings, demonstrating …

September 23, 2024

Leading change

September 19, 2024

First look at new Lakewood facilities

New medical offices will enhance the health care experience for members …

July 2, 2024

Reducing cultural barriers to food security

To reduce barriers, Food Bank of the Rockies’ Culturally Responsive Food …

June 28, 2024

Health Action Summit highlights mental health opportunities

The Kaiser Permanente Colorado Health Action Summit gathered nonprofits, …

June 3, 2024

A call to ‘Connect’ for cancer prevention research

Participate in a study to help uncover the causes of cancer and how to …

May 3, 2024

Henry J. Kaiser: America’s health care visionary

Kaiser was a major figure in the construction, engineering, and shipbuilding …

April 8, 2024

Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream is alive at Kaiser Permanente

Greg A. Adams, chair and chief executive officer of Kaiser Permanente, …

March 19, 2024

Fostering responsible AI in health care

With the right policies and partnerships, artificial intelligence can lead …

February 13, 2024

A legacy of life-changing community support and partnership

The Kaiser Permanente Watts Counseling and Learning Center started as a …

February 2, 2024

Expanding medical, social, and educational services in Watts

Kaiser Permanente opens medical offices and a new home for the Watts Counseling …

January 31, 2024

Prioritizing policies for health and well-being in Colorado

CityHealth’s 2023 Annual Policy Assessment awards cities for their policies …

December 20, 2023

Research transforms care for people with multiple sclerosis

Our researchers are leading the way to more effective, affordable, and …

December 15, 2023

Climate change is already affecting our health

The health care industry is responsible for 8% to 10% of harmful emissions …

December 6, 2023

Leaders named among health care’s most influential

Greg A. Adams; Maria Ansari, MD, FACC; and Ramin Davidoff, MD, have been …

October 23, 2023

The future of health care is digital

Nari Gopala, Kaiser Permanente’s chief digital officer, answers 3 questions …

October 17, 2023

How Kaiser Permanente evolved

Sidney R. Garfield, MD, and Henry J. Kaiser came together to pioneer an …

October 4, 2023

An easier way to manage multiple prescriptions

If you have an ongoing health condition, you know it can be tricky to keep …

September 27, 2023

10 school districts receive next round of RISE grants

The Thriving Schools program helps educators and students in Colorado integrate …

September 13, 2023

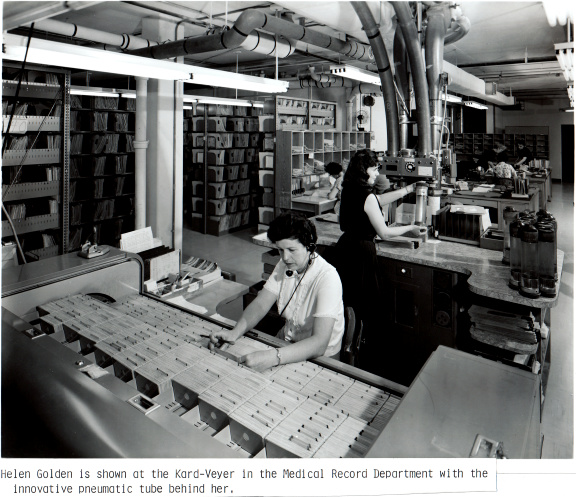

Transforming the medical record

Kaiser Permanente’s adoption of disruptive technology in the 1970s sparked …

September 8, 2023

Regulated waste settlement in California

We are committed to the well-being of the environment and protecting the …

August 7, 2023

Kaiser Permanente opens new medical center in San Marcos

The new medical center in San Diego County expands access and care for …

May 2, 2023

Women lead an industrial revolution at the Kaiser Shipyards

Early women workers at the Kaiser shipyards diversified home front World …

April 25, 2023

Hannah Peters, MD, provides essential care to ‘Rosies’

When thousands of women industrial workers, often called “Rosies,” joined …

November 11, 2022

A history of leading the way

For over 75 innovative years, we have delivered high-quality and affordable …

November 11, 2022

Pioneers and groundbreakers

Learn about the trailblazers from Kaiser Permanente who shaped our legacy …

November 11, 2022

Our integrated care model

We’re different than other health plans, and that’s how we think health …

November 11, 2022

Our history

Kaiser Permanente’s groundbreaking integrated care model has evolved through …

October 14, 2022

Contact Heritage Resources

October 6, 2022

We’re a Fast Company Innovation by Design winner

Kaiser Permanente is the first health care organization to win Design Company …

October 1, 2022

Innovation and research

Learn about our rich legacy of scientific research that spurred revolutionary …

August 16, 2022

Our support for the Inflation Reduction Act

A statement from chair and chief executive Greg A. Adams on the importance …

May 26, 2022

Nurse practitioners: Historical advances in nursing

A doctor shortage in the late 1960s and an innovative partnership helped …

September 10, 2021

‘Baby in the drawer’ helped turn the tide for breastfeeding

This innovation in rooming-in allowed newborns to stay close to mothers …

August 25, 2021

Kaiser Permanente’s history of nondiscrimination

Our principles of diversity and our inclusive care began during World War …

July 22, 2021

A long history of equity for workers with disabilities

In Henry J. Kaiser’s shipyards, workers were judged by their abilities, …

June 2, 2021

Path to employment: Black workers in Kaiser shipyards

Kaiser Permanente, Henry J. Kaiser’s sole remaining institutional legacy, …

February 22, 2021

The Permanente Richmond Field Hospital

Forlorn and all but forgotten, it played a proud role during the World …

September 28, 2020

A legacy of disruptive innovation

Proceeds from a new book detailing the history of the Kaiser Foundation …

August 26, 2020

Kaiser Permanente’s pioneering nurse-midwives

The 1970s nurse-midwife movement transformed delivery practices.

July 30, 2020

Books and publications about our history

Interested in learning more about the history of Kaiser Permanente and …

May 18, 2020

Nurses step up in crises

Kaiser Permanente nurses have been saving lives on the front lines since …

November 8, 2019

Swords into stethoscopes — veterans in health professions

Kaiser Permanente has actively hired veterans in all capacities since World …

August 28, 2019

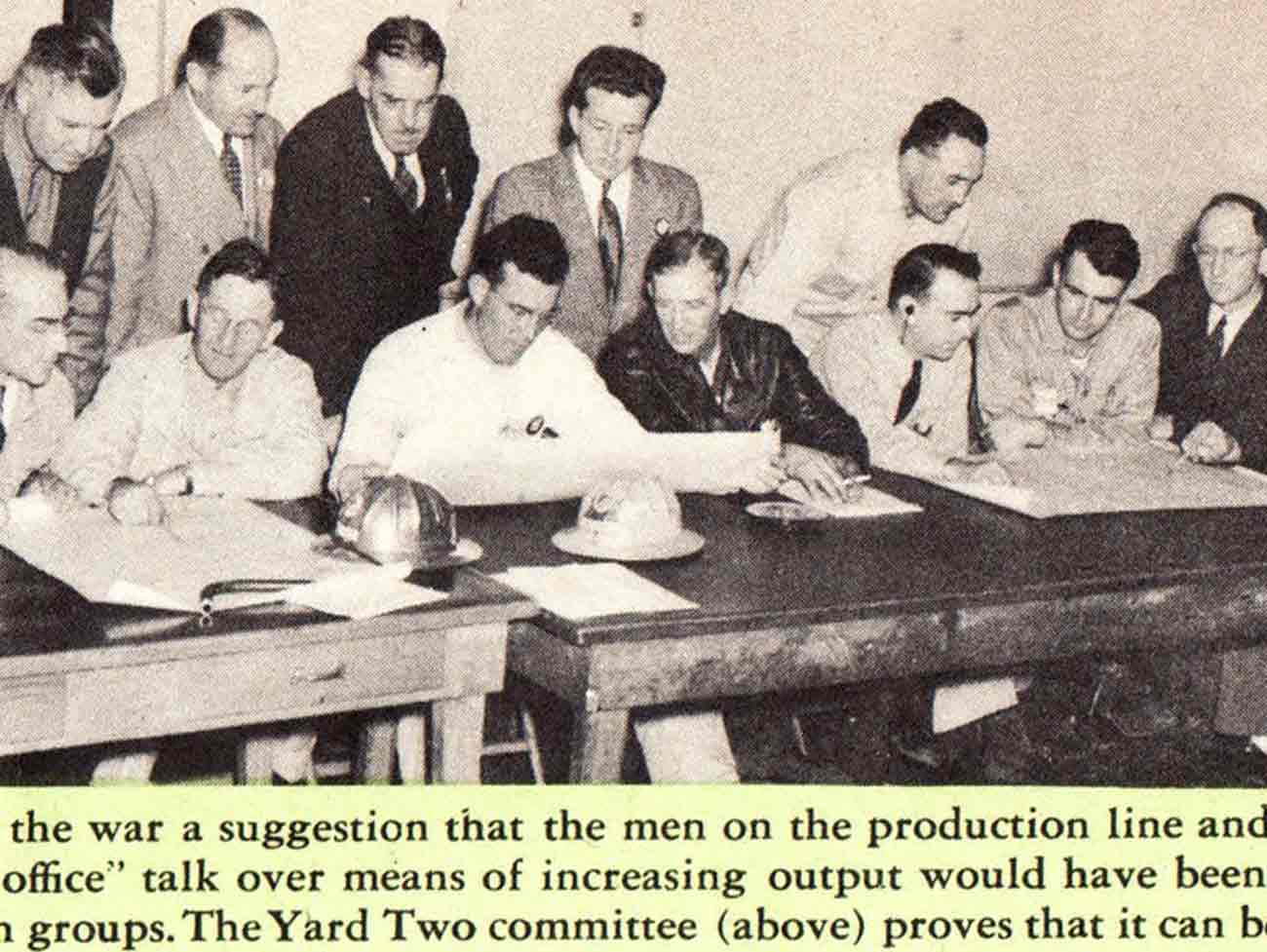

When labor and management work side by side

From war-era labor-management committees to today’s unit-based teams, cooperation …

August 2, 2019

Thriving with 1960s-launched KFOG radio

Kaiser Broadcasting radio connected listeners, while TV stations brought …

June 5, 2019

Breaking LGBT barriers for Kaiser Permanente employees

“We managed to ultimately break through that barrier.” — Kaiser Permanente …

March 29, 2019

Equal pay for equal work

Kaiser shipyards in Oregon hired the first 2 female welders at equal pay …

February 5, 2019

Mobile clinics: 'Health on wheels'

Kaiser Permanente mobile health vehicles brought care to people, closing …

December 10, 2018

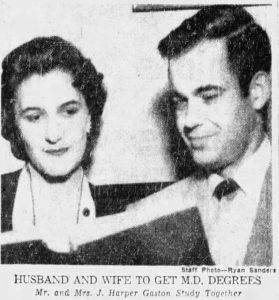

Southern comfort — Dr. Gaston and The Southeast Permanente Medical Group

Local Atlanta physicians built community relationships to start Kaiser …

July 31, 2018

Climate action

July 31, 2018

Environmental stewardship

May 30, 2018

John Graham Smillie, MD, pediatrician and innovator

Celebrating the life of a pioneering pediatrician who inspired the baby …

April 30, 2018

Nursing pioneers leads to a legacy of leadership

Kaiser Foundation School of Nursing students learned a new philosophy emphasizing …

April 12, 2018

Harold Hatch, health insurance visionary

The founding of Kaiser Permanente's concept of prepaid health care in the …

March 26, 2018

5 physicians who made a difference

Meet 5 outstanding doctors who advanced the practice of medical care with …

March 13, 2018

Henry J. Kaiser and the new economics of medical care

Kaiser Permanente’s co-founder talks about the importance of building hospitals …

March 8, 2018

Slacks, not slackers — women’s role in winning World War II

Women who worked in the Kaiser shipyards helped lay the groundwork for …

February 22, 2018

The amazing true story of Park Ranger Betty Reid Soskin

She is the oldest national park ranger in the country with a legacy of …

December 19, 2017

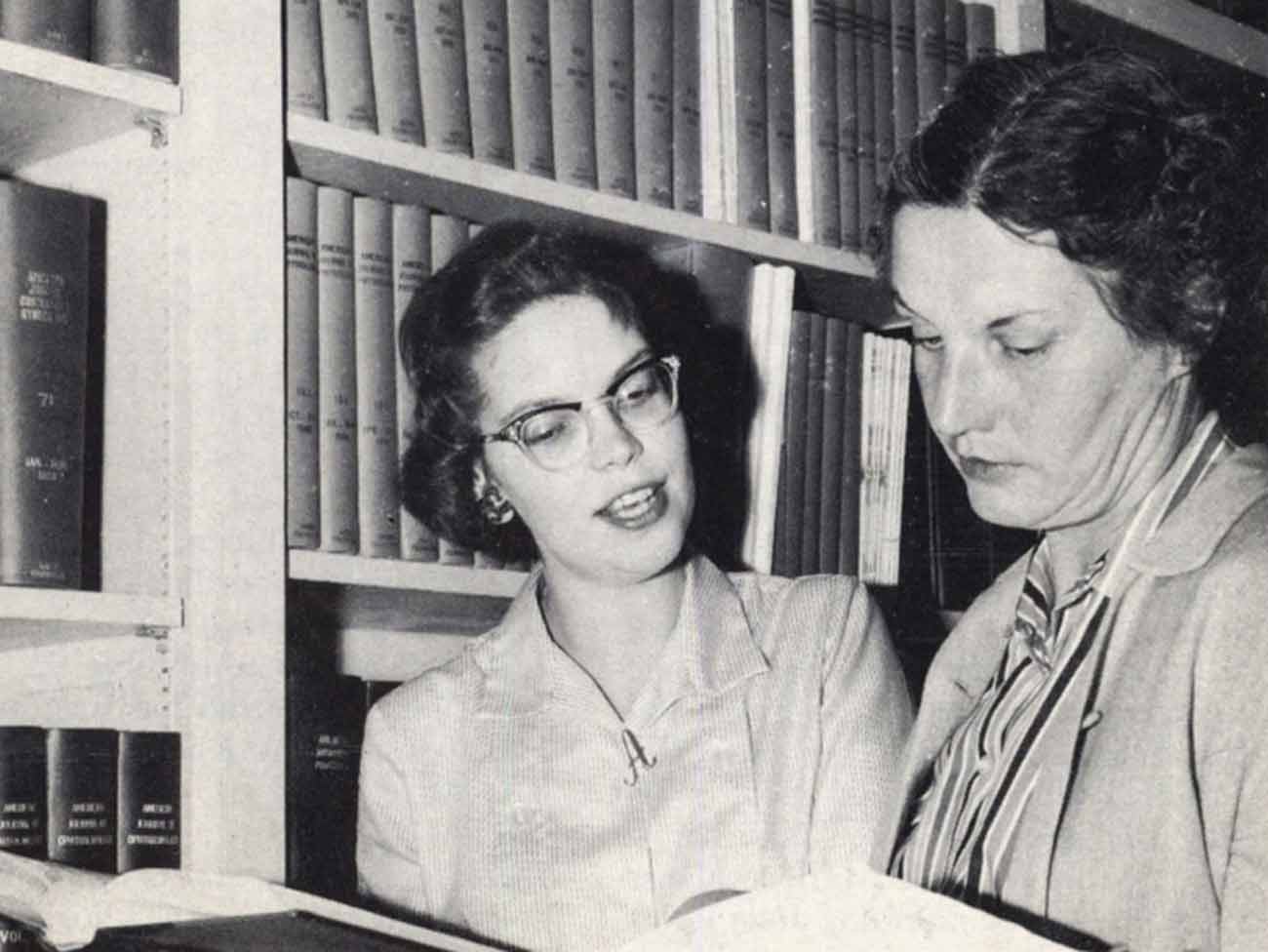

From boats to books: A history of Kaiser Permanente’s medical libraries

Kaiser Permanente librarians are vital in helping clinicians remain updated …

November 7, 2017

Patriot in pinstripes: Honoring veterans, home front, and peace

Henry J. Kaiser's commitment to the diverse workforce on the home front …

October 12, 2017

An experiment named Fabiola

Health care takes root in Oakland, California.

September 29, 2017

Harbor City Hospital: Beachhead for labor health care

The story of Kaiser Permanente's South Bay Medical Center finds its roots …

August 15, 2017

Sidney R. Garfield, MD, on medical care as a right

Hear Kaiser Permanente’s physician co-founder talk about what he learned …

August 10, 2017

‘Good medicine brought within reach of all'

Paul de Kruif, microbiologist and writer, provides early accounts of Kaiser …

July 14, 2017

Kaiser’s role in building an accessible transit system

Harold Willson, an employee, and an advocate for accessible transportation, …

July 7, 2017

Mending bodies and minds — Kabat-Kaiser Vallejo

The expanded new location provided care to a greater population of members …

June 23, 2017

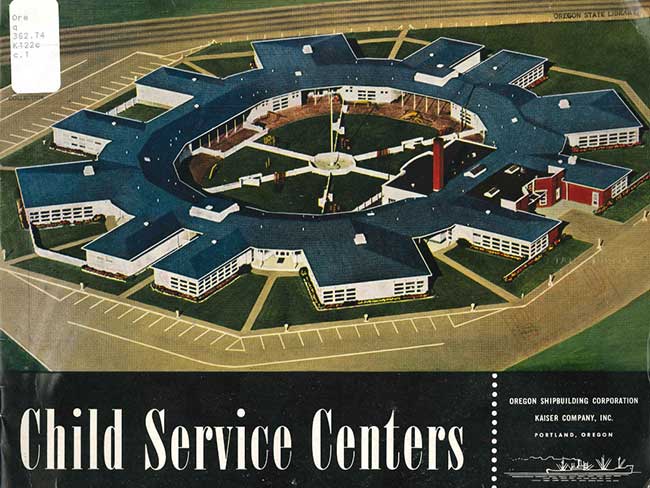

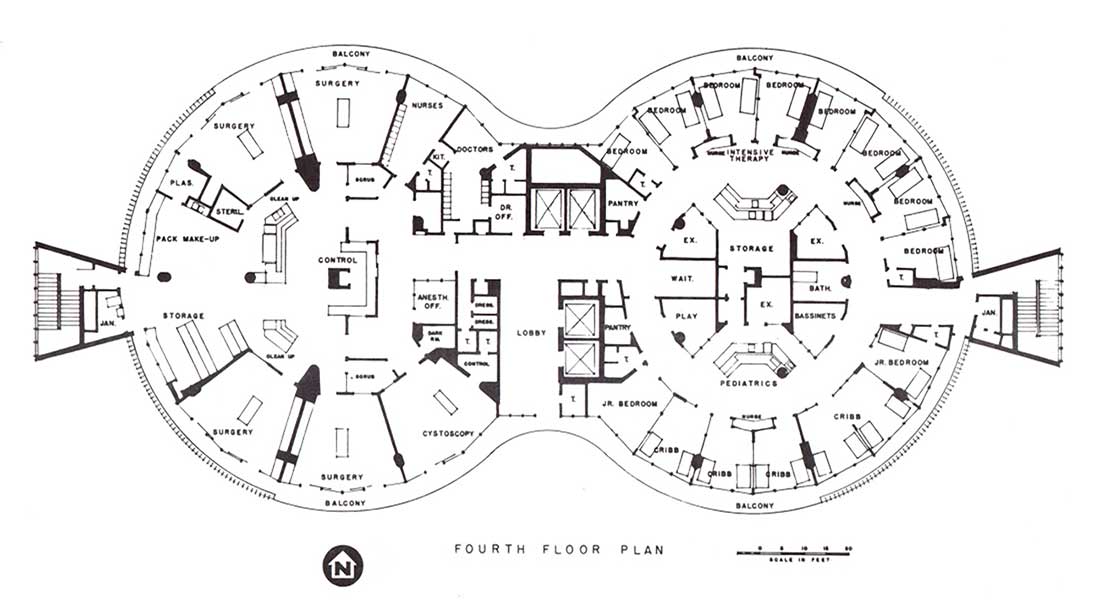

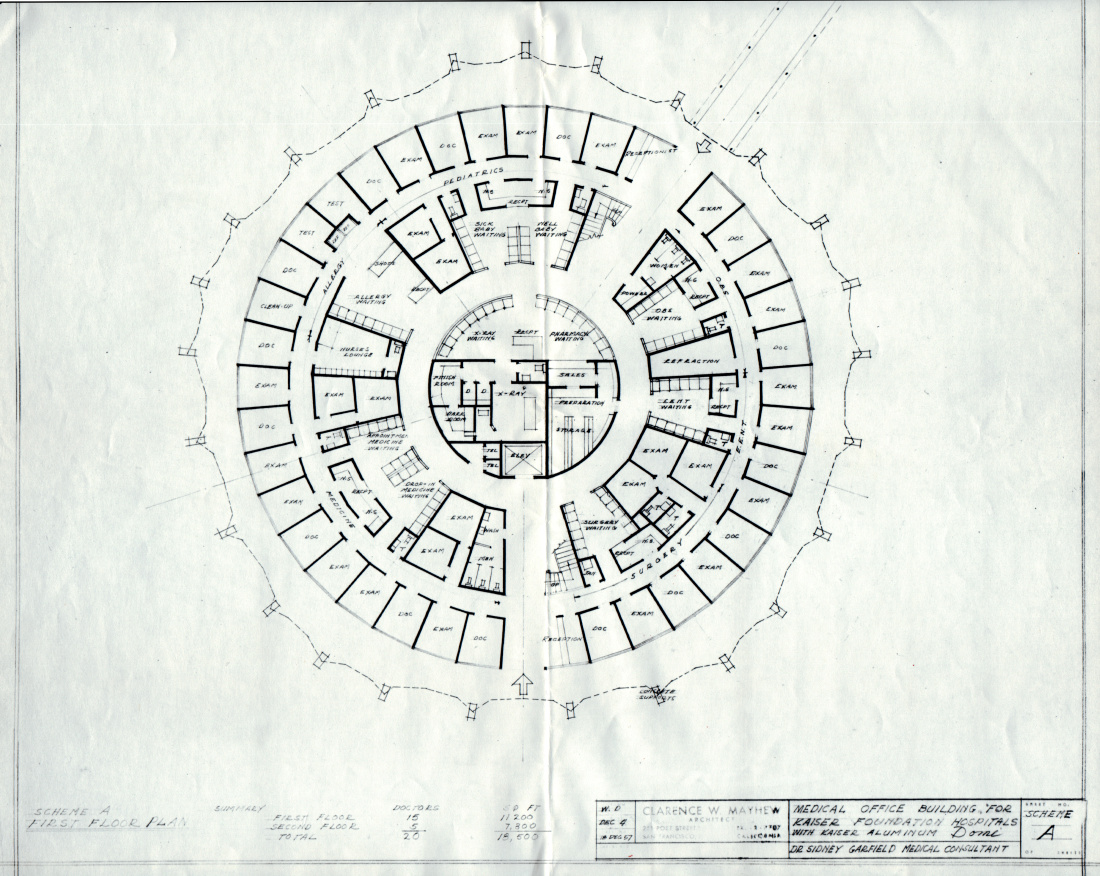

No getting round it: An innovative approach to building design

Kaiser Permanente incorporated innovative circular architectural designs …

June 14, 2017

Kabat-Kaiser: Improving quality of life through rehabilitation

When polio epidemics erupted, pioneering treatments by Dr. Herman Kabat …

June 9, 2017

Edmund (Ted) Van Brunt, pioneer of electronic health records, dies at age …

Throughout his career, Dr. Van Brunt applied computers and databases in …

May 4, 2017

How a Kaiser Permanente nurse transformed health education

Kaiser Permanente's Health Education Research Center and Health Education …

March 22, 2017

Kaiser Permanente and Group Health Cooperative: Working together since …

The formation of Kaiser Permanente Washington comes from longstanding collaboration, …

March 7, 2017

Beatrice Lei, MD: From Shantou, China, to Richmond, California

She served as a role model and inspiration to the women physicians and …

March 1, 2017

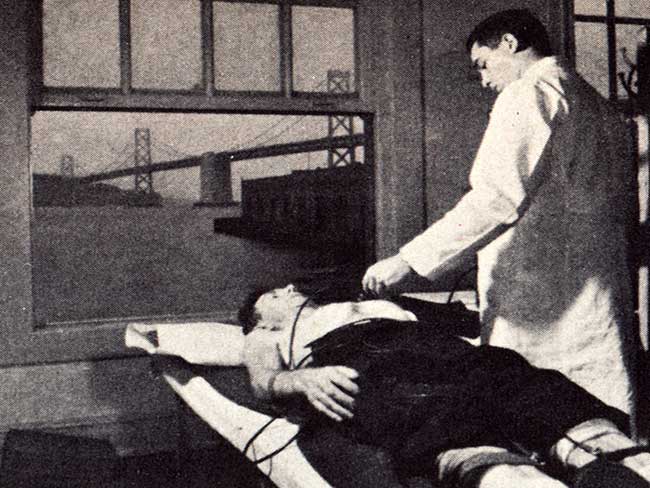

Screening for better health: Medical care as a right

When industrial workers joined the health plan, an integrated battery of …

February 17, 2017

Experiments in radial hospital design

The 1960s represented a bold step in medical office architecture around …

February 3, 2017

Ellamae Simmons — trailblazing African American physician

Ellamae Simmons, MD, worked at Kaiser Permanente for 25 years, and to this …

January 27, 2017

Japanese-American doctors overcame internment setbacks

Despite restrictive hiring practices after World War II, Kaiser Permanente …

November 16, 2016

Betty Reid Soskin honored with lifetime achievement award

The California Studies Association presents the Carey McWilliams Award …

October 17, 2016

Kaiser Motors in Oakland — “We sell to make friends.”

In 1946 Henry J. Kaiser Motors purchased half a square block in downtown …

October 12, 2016

Kaiser’s geodesic dome clinic

There are hospital rounds, and there are round hospitals.

May 5, 2016

Male nursing pioneers

Groundbreaking male students diversify the Kaiser Foundation School of …

April 20, 2016

Henry J. Kaiser’s environmental stewardship

Since the 1940s, Kaiser Industries and Kaiser Permanente have a long history …

November 13, 2015

Dr. Morris Collen’s last book on medical informatics

The last published work of Morris F. Collen, MD, one of Kaiser Permanente’s …

October 29, 2015

From paper to pixels — the new paradigm of electronic medical records

Transitioning to electronic health records introduced new approaches, skills, …

September 23, 2015

Kaiser Permanente and NASA — taking telemedicine out of this world

Kaiser Permanente International designs, develop, and test a remote health …

July 22, 2015

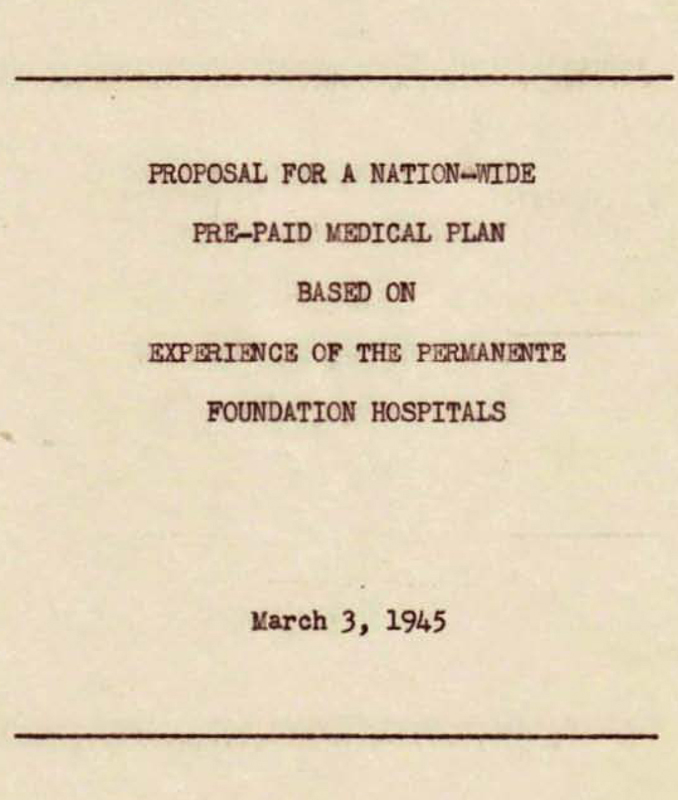

Kaiser Permanente as a national model for care

Kaiser Permanente proposed a revolutionary national health care model after …

July 21, 2015

Kaiser Permanente's early support from labor

Experiencing the Kaiser Permanente health plan led labor unions to support …

July 20, 2015

Opening the Permanente plan to the public

On July 21, 1945, Henry J. Kaiser and Dr. Sidney Garfield offered the health …

July 1, 2015

Sculpture dedicated to Kaiser Nursing School

The Kaiser Foundation School of Nursing sculpture near Kaiser Oakland hospital …

May 6, 2015

Celebrating Betty Runyen — Kaiser Permanente’s ‘founding nurse’

In a desert hospital during the Great Depression, Betty Runyen overcame …

April 27, 2015

Eugene Hickman, MD — Pioneering Black physician

Dr. Hickman had a long career at Kaiser Permanente, becoming president …

April 24, 2015

2 historical reflections on Kaiser Permanente

April 2, 2015

Henry Kaiser’s escort carriers and the Battle of Leyte Gulf

January 9, 2015

The World War II Kaiser Richmond shipyard labor force

December 16, 2014

Henry J. Kaiser on veteran employment and benefits

December 11, 2014

Henry J. Kaiser, geodesic dome pioneer

October 8, 2014

Breast cancer isn’t just a woman’s issue

July 23, 2014

Kaiser shipyards pioneered use of wonder drug penicillin

Though supplies for civilians were limited, Dr. Morris Collen’s wartime …