How Kaiser Permanente evolved

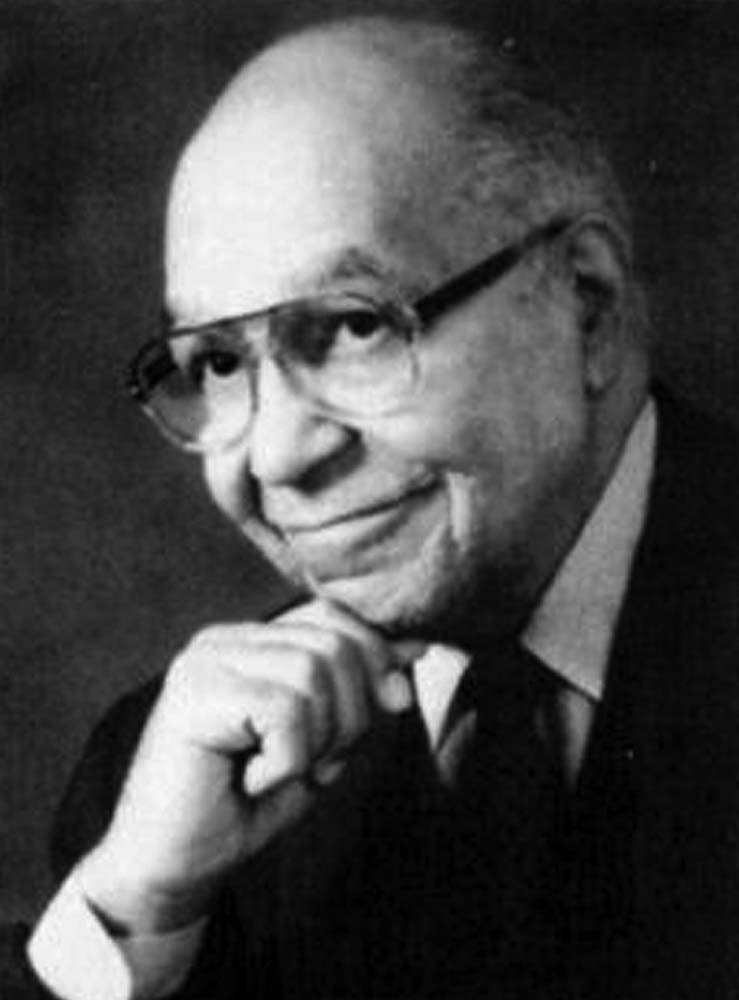

Sidney R. Garfield, MD, and Henry J. Kaiser came together to pioneer an innovative health care model.

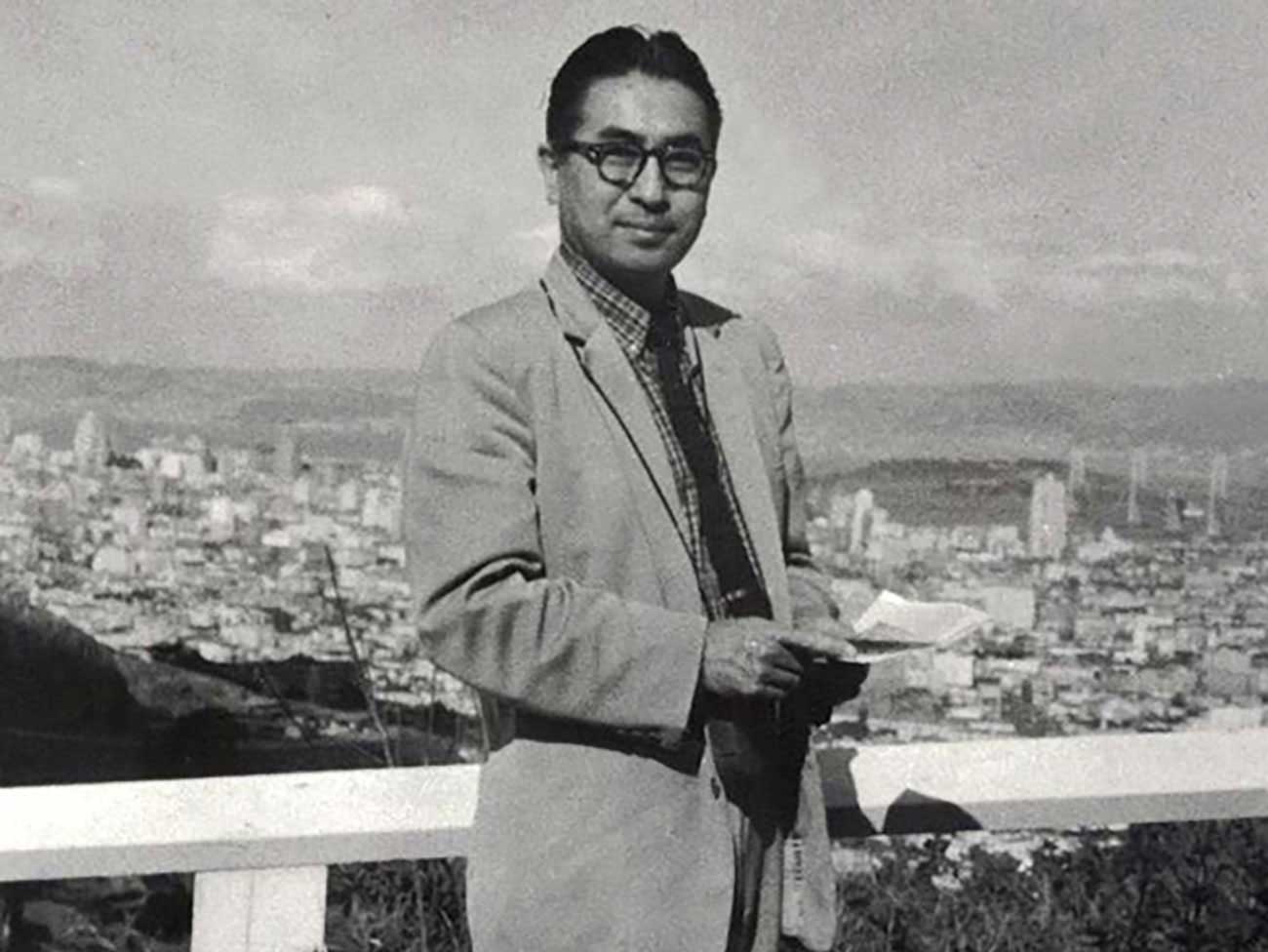

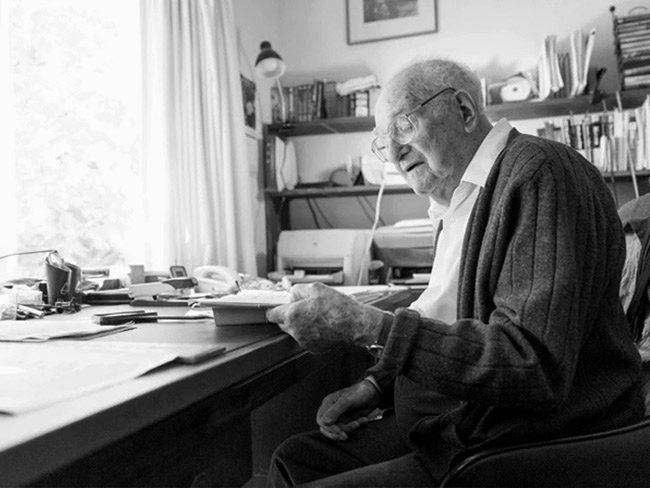

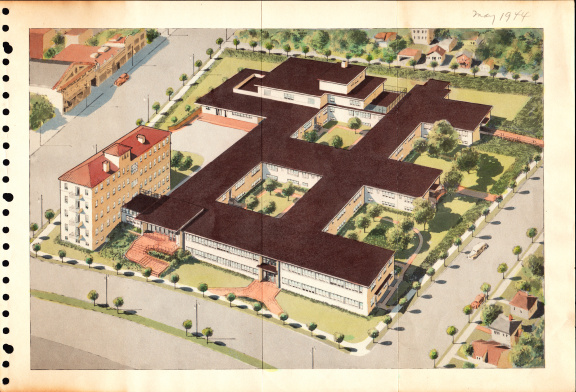

Sidney R. Garfield, MD, and Henry J. Kaiser review designs for 3 modern Kaiser Permanente hospitals for Walnut Creek, San Francisco, and Los Angeles in 1953.

Momentous events like the Great Depression and World War II defined a new generation in America. Young surgeon Sidney R. Garfield, MD, and industrialist Henry J. Kaiser became leading visionaries and pioneers in this new generation. They co-founded Kaiser Permanente in 1945 and introduced a revolutionary health care model. One that integrated preventive and evidence-based care with ultramodern technology.

Rising during the Great Depression

In 1933, Dr. Garfield found himself amid the worldwide economic downturn known as the Great Depression. Fresh from a Los Angeles County Hospital residency, he accepted the opportunity to care for thousands of workers building the Colorado River Aqueduct in the Southern California desert.

Dr. Garfield borrowed money to help fund the construction of Contractors General Hospital, about 6 miles west of Desert Center, California. He and another doctor established a partnership to run the small hospital. It featured advanced medical equipment and air conditioning. Dr. Garfield became the only physician caring for thousands of workers when his physician partner left. He had a small staff, including Kaiser Permanente’s founding nurse, Betty Runyen, RN.

Dr. Garfield (far right) stands with a nurse in front of a car, and Betty Runyen, RN, at the wheel, 1933.

In 1933, nurses didn’t usually perform tasks like starting an IV. But Runyen learned advanced skills working with the forward-thinking Dr. Garfield. She put these skills to work after receiving an emergency call one day while Dr. Garfield was away. She drove the hospital ambulance to a job site and started a saline IV that saved a worker who had collapsed from heat exhaustion.

Experimenting with prepayment

Dr. Garfield prioritized workers’ wellness and health. He and his team accepted sick or injured workers even when their insurance refused coverage. Unfortunately, the lack of steady payments threatened the hospital’s continued operations. Industrialist Henry J. Kaiser, one of the aqueduct’s contractors, organized an insurance company, Industrial Indemnity Exchange, for his workers. Hearing that the only hospital would soon close, Kaiser sent insurance executive Harold Hatch to meet with Dr. Garfield and come up with a solution to keep the hospital open.

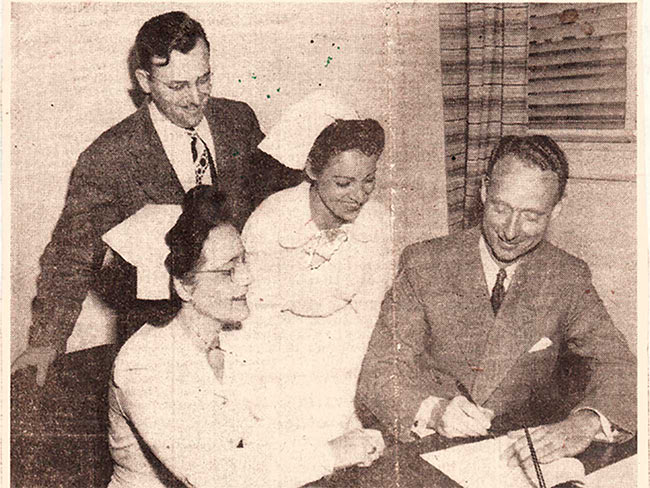

Working together toward a plan, Industrial Indemnity Exchange agreed to prepay Dr. Garfield a fixed amount per worker per day for work-related injuries and health care. Workers then voluntarily prepaid a premium of 5 cents per day from their paycheck for non-work-related health care. This agreement provided workers with comprehensive care without extra out-of-pocket costs. Thousands of workers enrolled, keeping the hospital in operation.

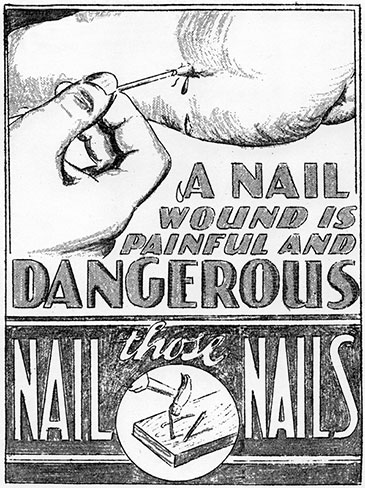

This prepayment system allowed Dr. Garfield to maintain the hospital’s finances and operations, allowing him and Runyen to focus on workers’ health and safety instead of treating acute illness and injury. They started educating the workers on maintaining a clean worksite and always keeping their hard hats on. Soon, preventable injuries like nail wounds became less common. As the aqueduct project neared completion, Dr. Garfield prepared to leave the desert hospital to start a private practice in Los Angeles.

Before leaving, he received a call and request to provide health care to over 6,500 workers and their families at the Grand Coulee Dam worksite.

Expanding care with group practice

Industrialist Henry J. Kaiser and his construction company at Grand Coulee Dam needed high-quality care for workers and families. Dr. Garfield agreed to visit the site and evaluate the situation. He decided to stay and develop a similar prepayment care program for the small, industrial, close-knit town.

One of the posters published at Grand Coulee Dam to prevent industrial injuries by encouraging clean and safe worksites.

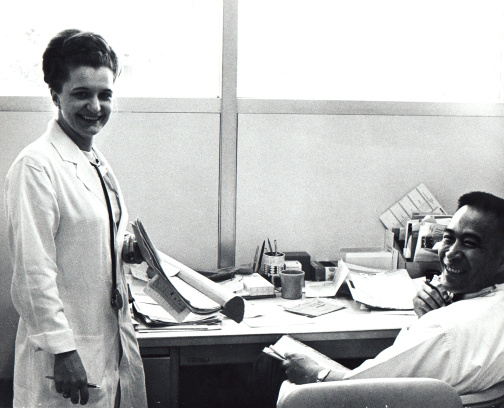

Kaiser partnered with Dr. Garfield to fund the hospital renovation and install air conditioning units. Unlike in the desert town where the Colorado River Aqueduct work took place, this town included families with children, which increased the amount and type of care needed. The Grand Coulee Dam care plan expanded the prepayment system to include spouses and dependents. Dr. Garfield hired doctors and nurses to work collaboratively as a group practice to meet members' needs.

The prepaid group practice flourished as workers and their families learned to stay healthy at work and home by seeking care early, preventing serious illnesses and death. As Grand Coulee Dam neared completion in 1941, the grand health care experiment entered its next phase.

Advancing care delivery for a nation in crisis

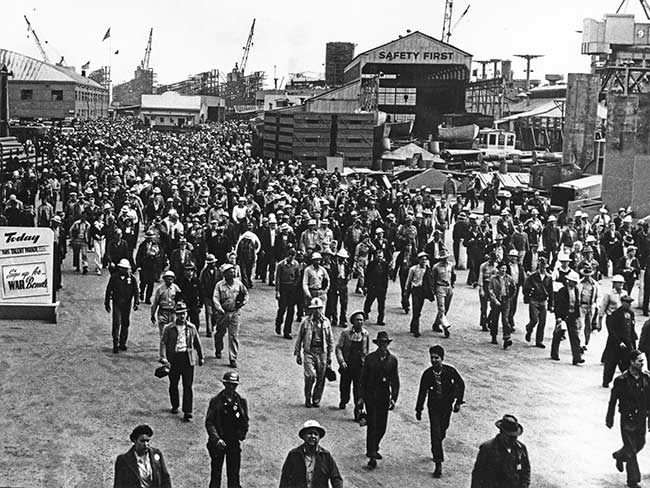

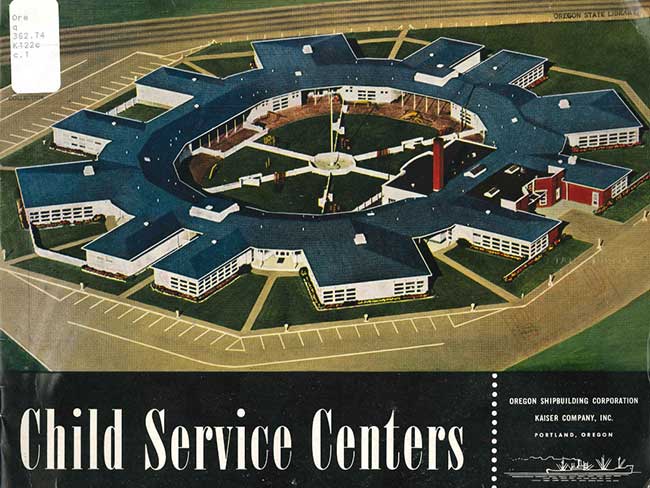

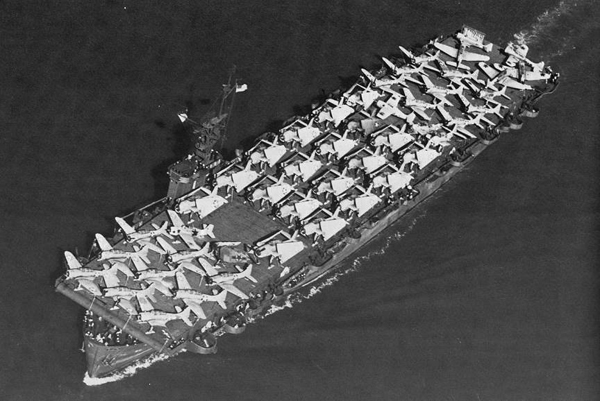

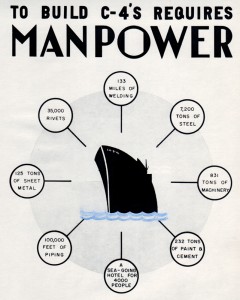

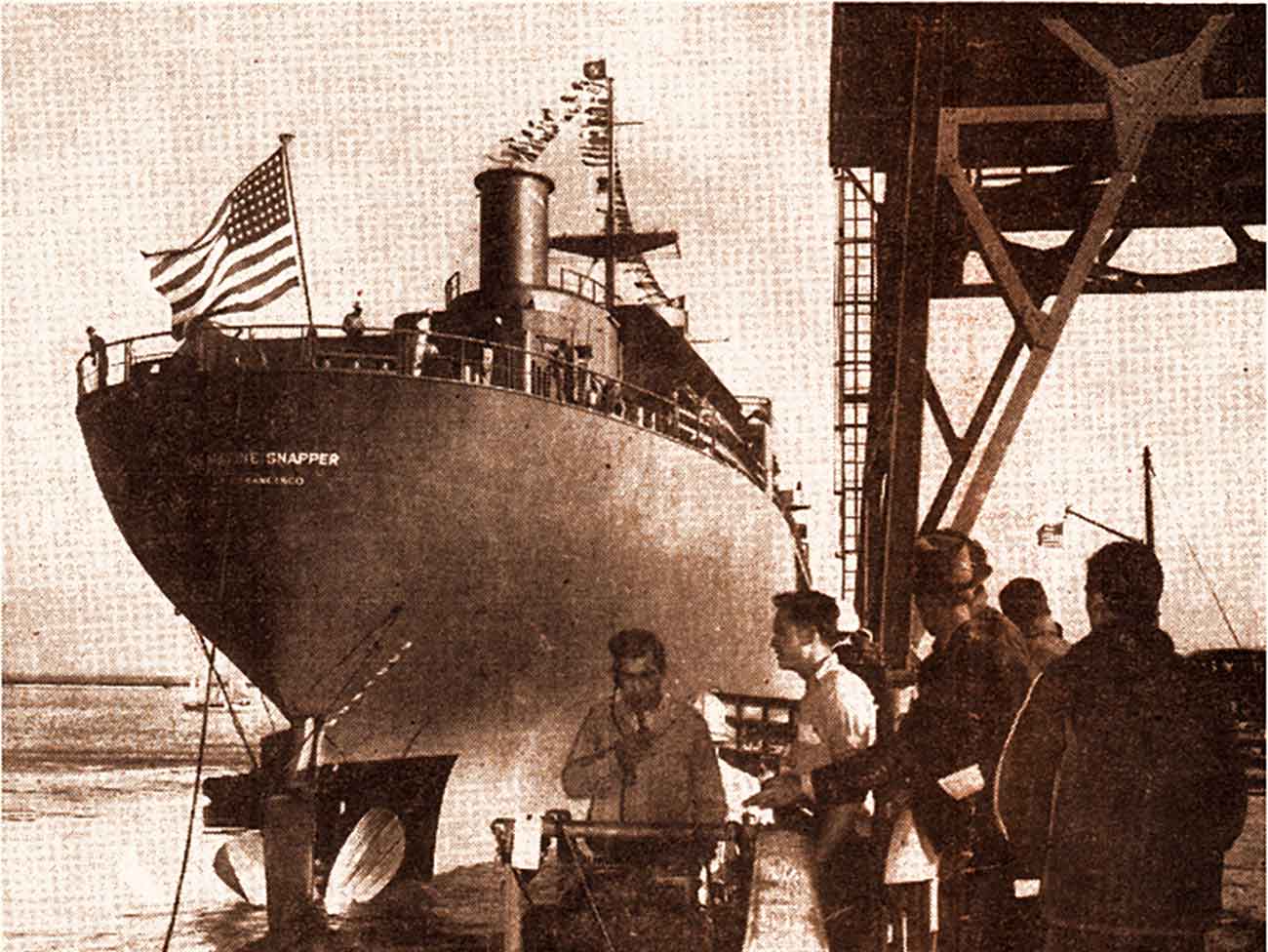

When America entered World War II in December of 1941, thousands of diverse workers migrated from across the country to Henry J. Kaiser’s shipyards in Richmond, California; Portland, Oregon; and Vancouver, Washington. They answered the patriotic call to build Liberty ships and aircraft carriers to help win the war. However, many workers were inexperienced and in poor health.

Kaiser realized workers and their families needed to stay healthy, and he became convinced that Dr. Garfield could help with a new solution. The young doctor was scheduled to enter active duty with his U.S. Army Reserve unit when President Franklin D. Roosevelt released him from his military obligation at Kaiser’s request to organize a care plan at the Kaiser shipyards.

Dr. Garfield called upon his previous experience with a prepaid group practice and again hired teams of doctors and nurses who organized into units to provide around-the-clock care to workers and family members across Kaiser’s shipyards for a prepaid cost.

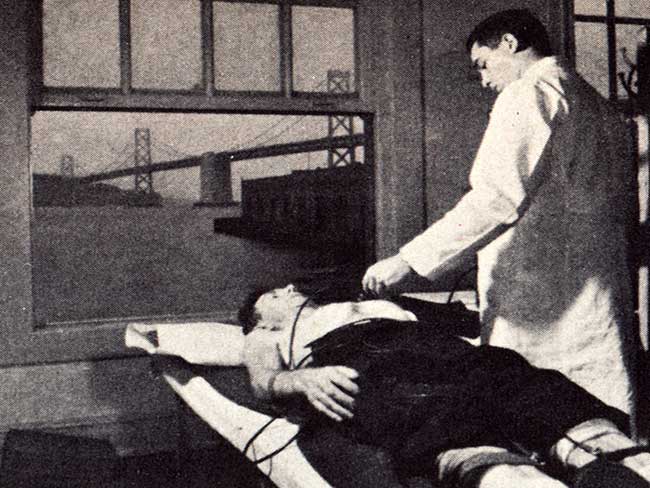

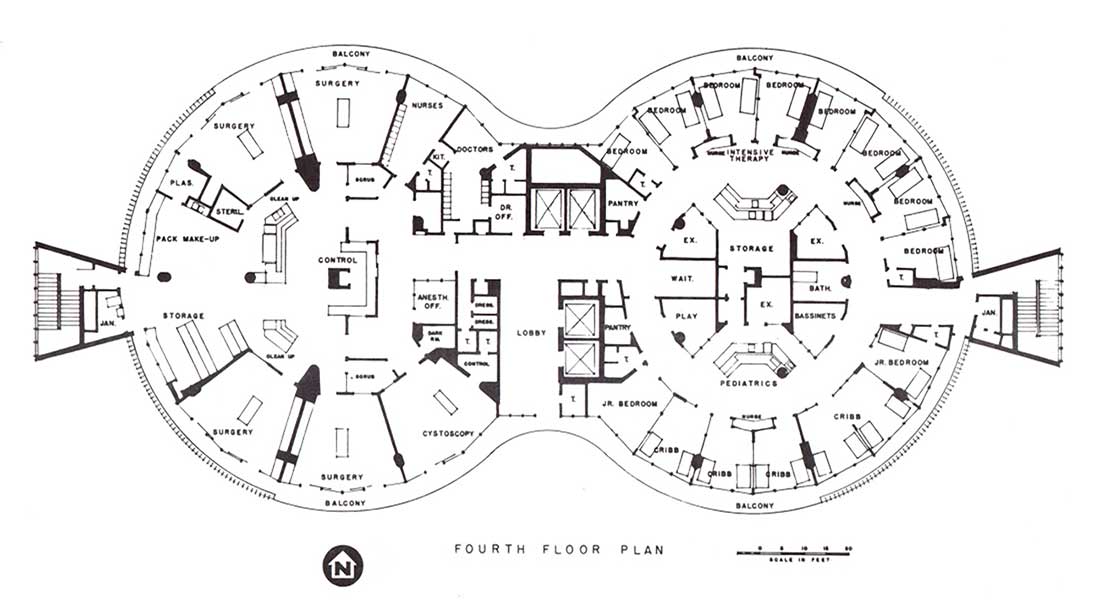

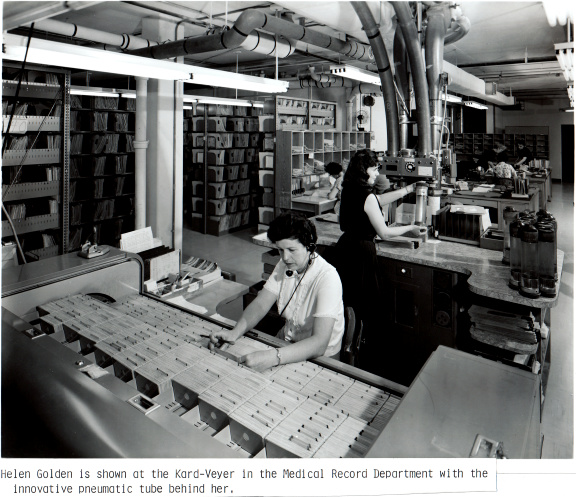

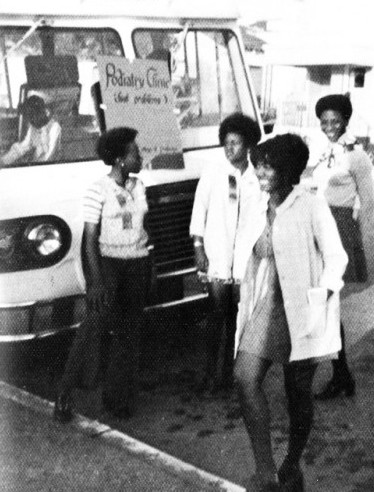

The shipyard care plan broke barriers by racially integrating its newly constructed first aid stations, field hospitals, and the first Kaiser Permanente Oakland Hospital. Workers of all races and genders and their families received equitable treatment. The Oakland Hospital services such as laboratory and pharmacy were combined in a single location, allowing doctors and nurses to collaborate on care and treatment plans with less delay.

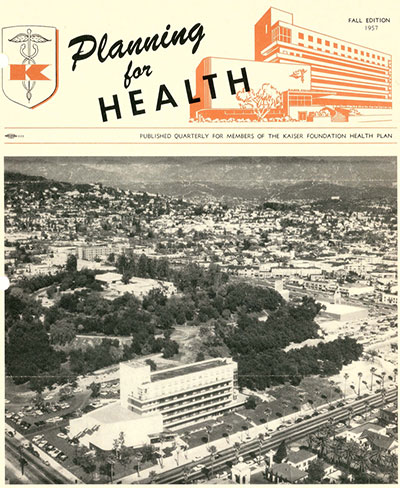

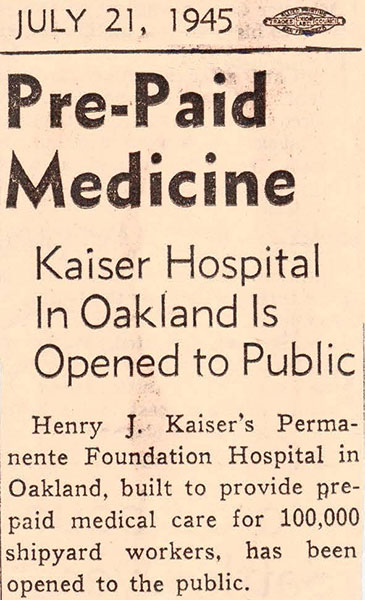

At a time of limited medicine and health care marketing, Kaiser Permanente announced its public opening in the newspaper after World War II ended.

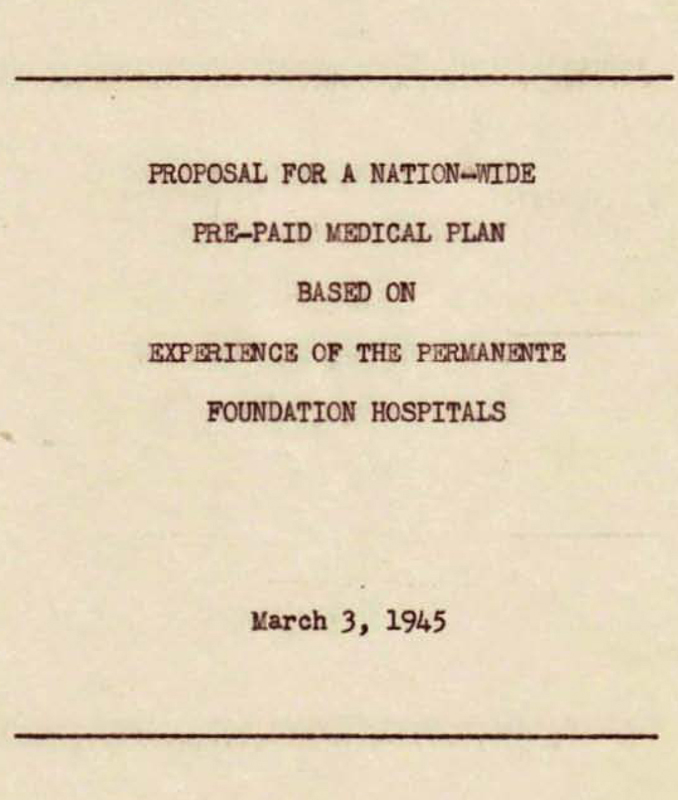

Introducing Kaiser Permanente

After World War II ended and American troops started to return home, the shipyard workforce fell from 90,000 to about 13,000 people in only a few months. The number of shipyard doctors declined to about a dozen.

But Dr. Garfield and Kaiser wanted to continue delivering health care in this new way. So, on July 21, 1945, the Permanente Health Plan officially opened to the public.

Enrollment surpassed 300,000 people in the first 10 years of the program thanks to support from the International Longshore and Warehouse Union and the Retail Clerks Union.

Today, Kaiser Permanente is based on the close cooperation between 3 entities: the nonprofit Kaiser Foundation Health Plan, Inc.; the nonprofit Kaiser Foundation Hospitals; and the Permanente Medical Groups. Our health plan, hospitals, and medical groups work together to offer personalized, convenient, and affordable care to our members.