Opening the Permanente plan to the public

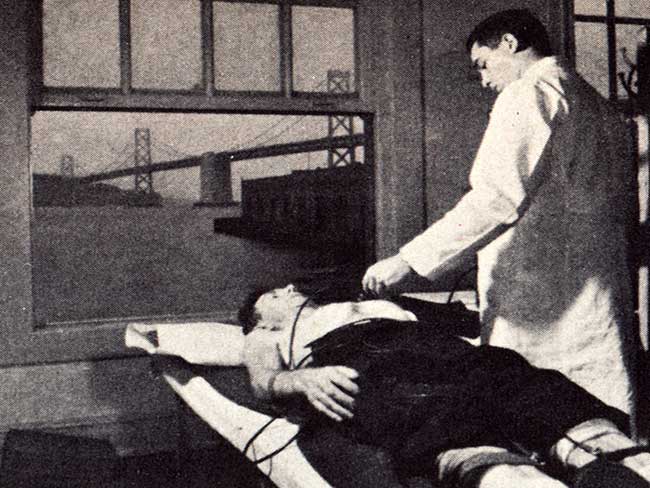

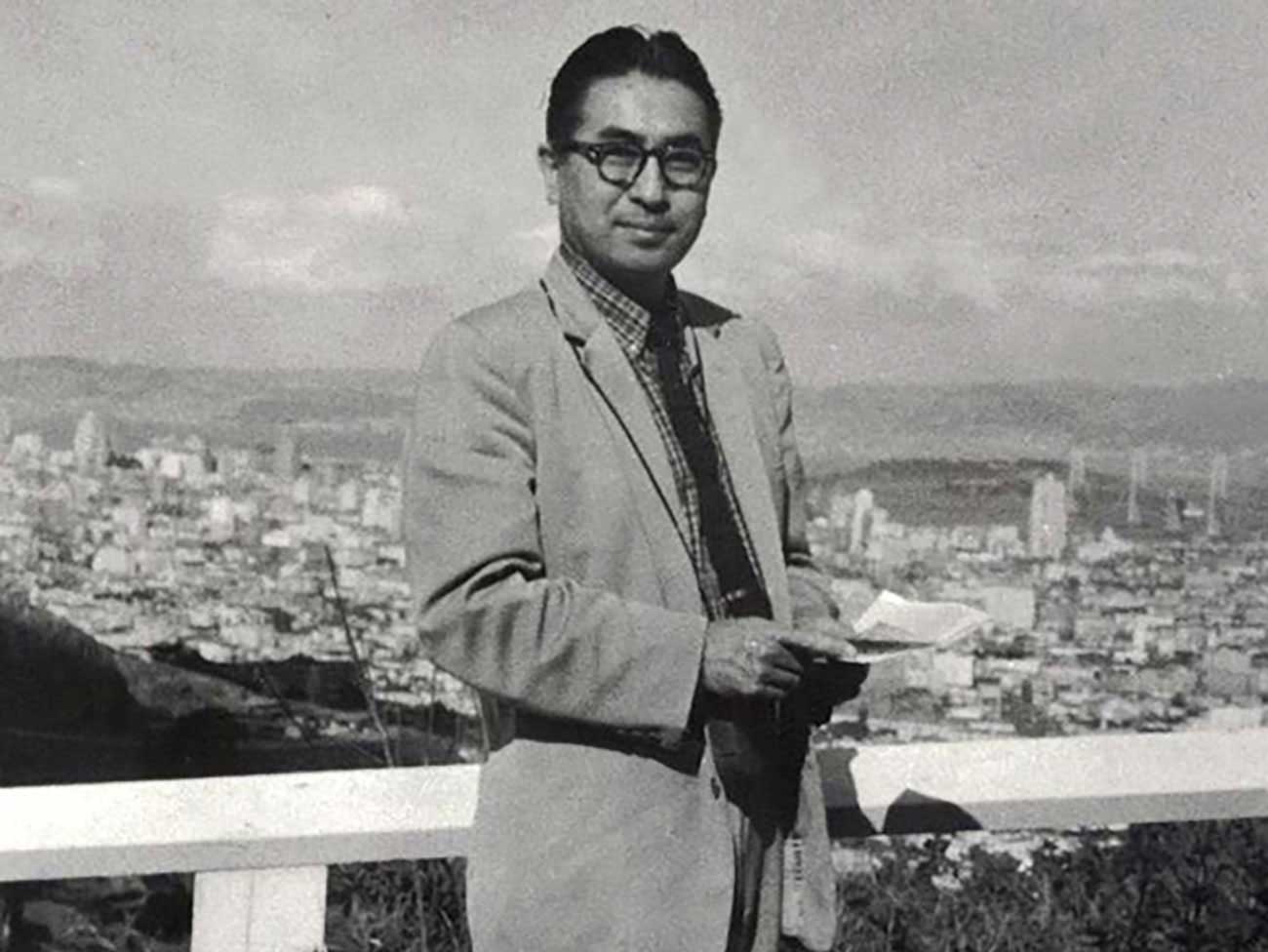

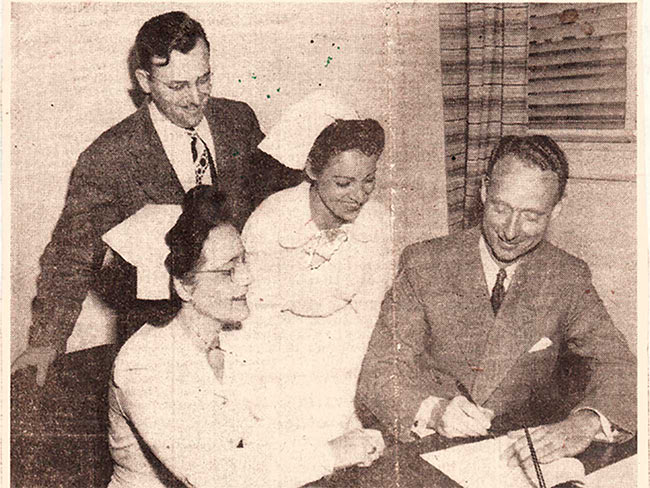

On July 21, 1945, Henry J. Kaiser and Dr. Sidney Garfield offered the health plan to the public, changing how families experienced preventive and integrated care.

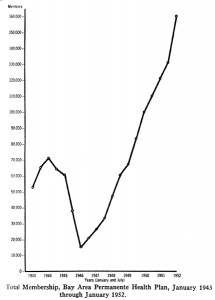

“Total Membership, Bay Area Permanente Health Plan, January 1943 through January 1952.” From “A Report on Permanente’s First Ten Years,” by Sidney Garfield, MD, in the Permanente Bulletin, August 1952.

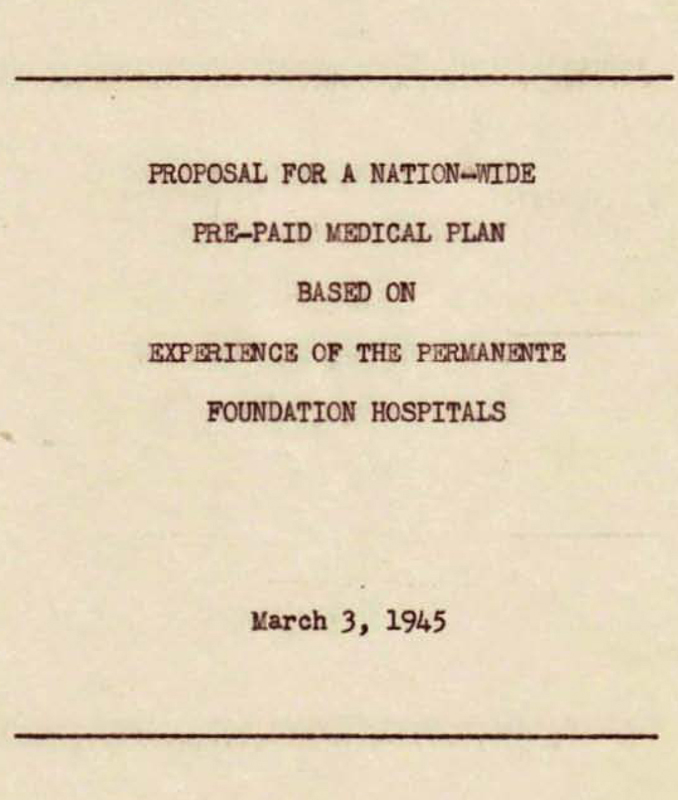

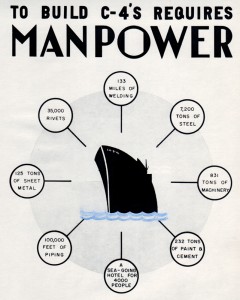

During World War II, Henry J. Kaiser’s 50-cent-a-week nonindustrial health plan for his shipyard workers was so overwhelmingly popular that the Permanente Health Plan had trouble keeping up with enrollment and facilities. But as the war neared its end, plans had to be made about whether or not to keep it going.

On July 21, 1945, Henry J. Kaiser and founding physician Dr. Sidney Garfield let it be known that their proven system of care would be open to the general public. The San Francisco Chronicle article led with this:

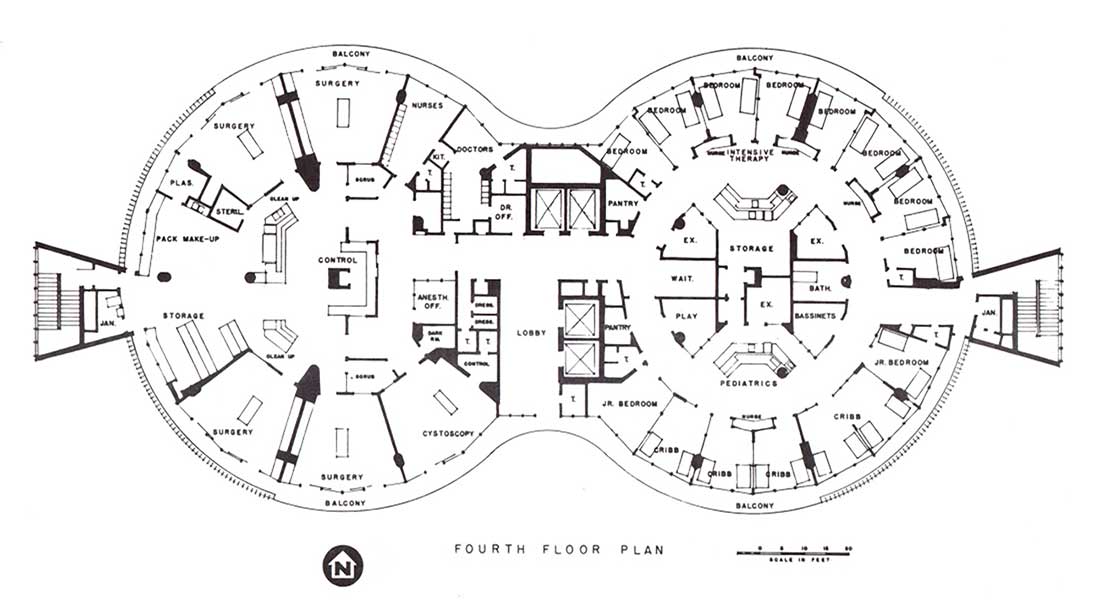

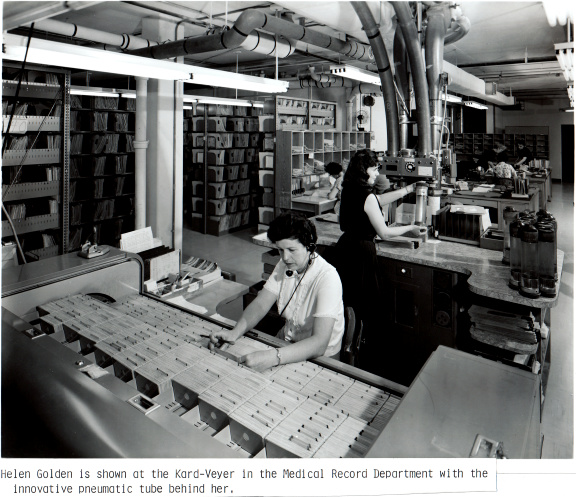

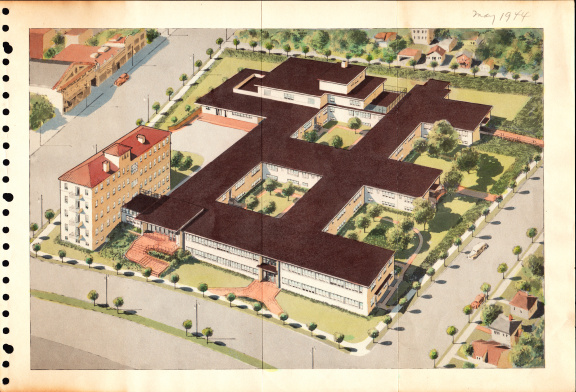

"Henry J. Kaiser’s Permanente Foundation Hospital in Oakland, built to provide pre-paid medical care for 100,000 shipyard workers, has been opened to the public. Clyde F. Diddle, administrator of the $2,000,000 hospital at Broadway and MacArthur Boulevard, said that any individual may walk into the hospital and apply for complete, prepaid medical care. Groups of 25 workers under one employer may also obtain medical service. The 300-bed hospital has 80 full-time physicians and surgeons, laboratories, clinics, and pharmacies."1

Before this, many industrialists had adopted programs to improve their workers’ health, but Henry J. Kaiser was the first to embrace the public.

In September of 1945, the Permanente Health Plan in the Northwest (Portland, Ore. area) followed suit. The only Kaiser hospital in Southern California was at the Fontana steel mill, and it would open to the public as well. In 1984 Dr. Garfield recalled that decision:

"The war ended, and we lost our [shipyard] membership, [but] the [Fontana] steel plant still continued. We had the facilities, we had a basic organization, and we had quite a few doctors who wanted to continue in prepaid medicine. I built up a contingency fund for this very purpose. I knew we would have a lapse at the end. We had [a] contingency fund. The whole thing was sort of a survival kit. The doctors decided they would like to continue. We had the organization. So we decided to open the plan to the community."

This shift had a profound impact on the wartime physicians working for the plan. Kaiser shipyard doctor Morris Collen, MD, reflected on this transition in his 1986 Regional Oral History Office interview:

"We were pleased when we were told that Dr. Garfield had decided to open the plan to the community. Already workers and their families were taken care of, so we were taking care of dependents--women and children. We had dropped down from 90,000 members to about 14,000 members in ’44. Of course, in order for us to survive, we had to get more members.

"Dr. Garfield called all the physicians together at a noon meeting, and he told us that, with the war over, we were now released from Procurement and Assignment; we could do whatever we wanted. Dr. Garfield told us that he hoped that most of us would want to stay, and he’d find jobs for us; and if not, he thanked us. Quite a few left. That’s when I made my decision that I’d enjoyed very much what I’d been doing; I wanted to keep doing it, and so I told him that I would like to stay. He said fine, and that’s how I continued on. Most of the key physicians did stay on and became the nucleus for the partnership."

And in 1962 Cecil Cutting, M.D., first executive director of The Permanente Medical Group, recalled the tension of those early years:

"In the shipyards, there’d been no lack of patients. A busload would arrive at the Richmond field hospital every 20 minutes. But as war ended and members remaining in the area wanted us to continue their medical care, we were faced with a big decision. Did the community want the pre-paid, group practice medical care that had worked well in an industry? Would early diagnosis and preventive medicine pay off for the members and for the Plan? Some of our physicians had accepted our type of practice only as a war measure. When the war was over they went into independent practice. But a core of physicians who believed in this method, and liked it, decided to remain. We had some lean years and hard struggles.Gradually the loyalty of members and our responsibility in maintaining economy and quality in medical care paid off." 2

And the rest is history.

1 “Pre-paid Medicine: Kaiser Hospital in Oakland is Opened to the Public,” S.F. Chronicle, July 21, 1945.

2 “Leaders Tell How — and Why — Health Plan Grew,” KP Reporter, May, 1962.