Screening for better health: Medical care as a right

When industrial workers joined the health plan, an integrated battery of preliminary examinations was far more useful than periodic checkups.

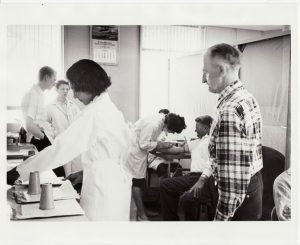

"This local 10 longshoreman is having an electrocardiograph taken to detect any heart irregularity. This is one of the many tests in the recent program conducted for the ILWU by Permanente." Planning for Health, Fall, 1951.

For many years a hallmark of Kaiser Permanente’s preventive health care program was a battery of tests, designed to alert doctors to trends and red flags in a patient’s health. And it started with service to industrial workers.

Lester Breslow, MD, published a seminal article in the March 1950 American Journal of Public Health titled “Multiphasic Screening Examinations: An Extension of the Mass Screening Technique.” Dr. Breslow, who worked for the California State Department of Public Health in Berkeley, challenged the limitations of periodic health examinations, and proposed the value of an integrated battery of preliminary examinations — a “multiphasic examination.” The advantages included a single combined medical record, cost savings, and improved diagnoses. One passage in Dr. Breslow’s article stood out:

“This survey can be conducted in a time not much greater than would be required for screening for a single disease. Where such screening procedures are carried out among industrial populations the time element is especially important.”

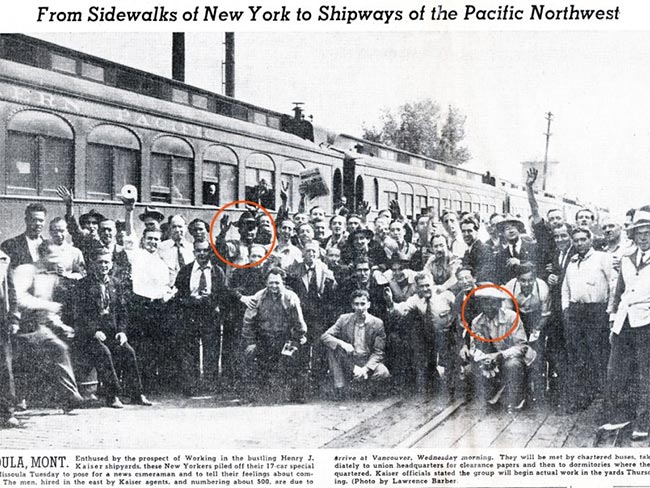

At that time, the Permanente Health Plan was expanding to the public after having only served Henry J. Kaiser’s World War II employees, and much of that growth was from unions. Dr. Breslow had been a college classmate of Kaiser Permanente’s Dr. Morris Collen, and the AJPH article offered a solution to the challenges of bringing in large numbers of industrial members with physically demanding jobs and poor health care.

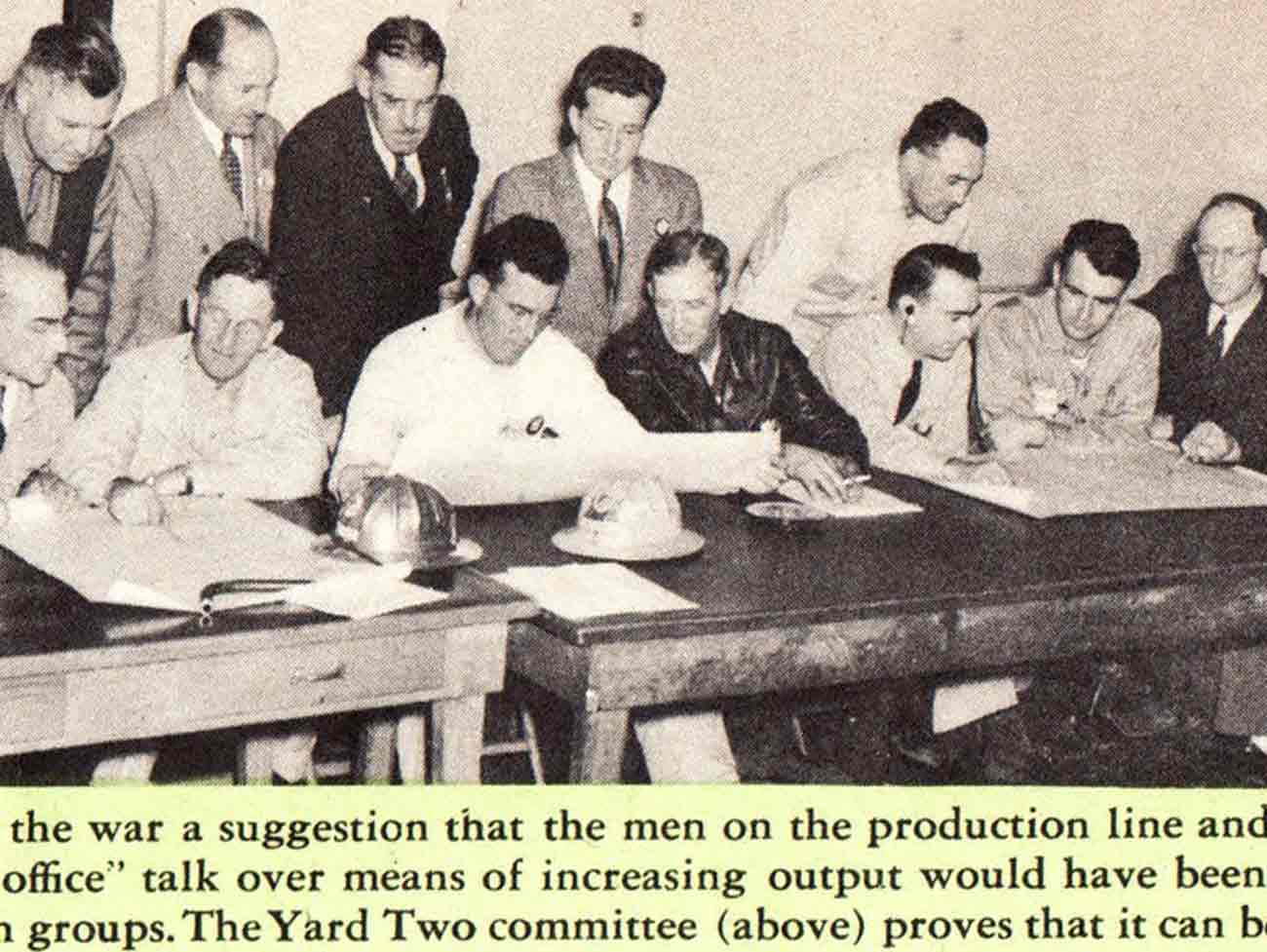

Since the main medical competitors, Blue Cross/Blue Shield did not provide health checkups unless one had a medical complaint, the Permanente facilities saw a surge in well-patient testing that began to drain the system. Searching for solutions, Dr. Collen spoke with Dr. Breslow, who suggested setting up a multiphasic screening for a large new member organization — the International Longshore and Warehouse Union. Although the screening was coordinated under Permanente’s leadership, it included the cooperation of the United States Public Health Service, the California State Department of Health, the San Francisco Public Health Department, the Bureau of Vocational Rehabilitation, and the San Francisco Tuberculosis Association.

The screening was seen as a groundbreaking step in public health. The ILWU Dispatcher article May 11, 1951 proclaimed:

"The longshoremen's program represents pioneer work in preventive medicine — the science of keeping people healthy. Multiple health tests for such a large group are a new procedure, in use only since 1948 and scientifically proved to be effective in detecting disease while there is still time for treatment."

Dr. Collen proceeded to try his first group test at the ILWU’s Local 10 hall at Pier 18 in San Francisco and screened several thousand longshoremen. An article in The Dispatcher from August 17, 1951, titled “ILWU Waterfront Health Tests ‘Complete Success’; 4,002 Go Through” boasted:

"Follow-up tests and treatment are now being given to members whose test results showed any signs of disease by a special team of Permanente doctors assigned to the ILWU under the ILWU·PMA [Pacific Maritime Association] Welfare Plan".

At a dinner for all the people who worked on the project, Permanente Health Plan, Director Dr. E. Richard Weinerman said the health test program was a "complete success . . . The fact that this program was the first to be organized by a union, the first to provide so comprehensive an array of tests, and the first to assure complete medical follow-up through the health plan made it an outstanding contribution to the field of preventive medicine."

Dr. Weinerman also noted the role of what we now call "culturally competent care." In a Dispatcher article on July 6, 1951, he said "In order to condition [our physicians] to do the best possible analysis, the union is taking them on a tour of the waterfront to observe working conditions. Then they will be able, to understand clearly how longshoremen work, and they can interpret symptoms more accurately."

Dr. Collen later recalled the next steps of expanding the screening to all Permanente members in his oral history:

"We started our multiphasic program in the Oakland clinic [on November 29, 1951]... After the clinics closed at five-thirty, we used the existing office space in the surgery clinic. We developed a whole series of arrows and put colored tapes on the floors so that patients would go in through the various rooms and have their height, weight, blood pressure, and other physiological measures taken, and then fill out a history form. Then they would be directed to the laboratory for blood and urine tests, to the x-ray department for a chest x-ray, and to the electrocardiography department for an electrocardiogram. In that way, we didn't require any extra equipment or any extra facility space. We developed a team of personnel that would work in the evenings from about five-thirty to eight, and we examined some twenty-five to thirty patients every evening that way at a very low cost."

In 1952, the Kaiser Permanente clinic at 515 Market Street in San Francisco also opened a Multiphasic Health Test facility in a space that had formerly been used as an orthopedic clinic.

The process consisted of about 15 procedures and only required the presence of a single physician, assisted by paramedics. Dr. Collen went on to explain the beautiful medical logic of the testing:

". . . Health is the only condition in life when you find people who are medically similar. That is, healthy people, have a relatively normal distribution of their tests and measurements so that you can develop routine repetitive procedures to do these tests. The health checkup, the evaluation of a normal well person, is the most routine, repetitive procedure in medicine."

As soon as one has a variation from normal, which is the basic definition of being ill or sick, then one becomes unique. Every diabetic is different; every hypertensive is different, and a diabetic with hypertension is even more complicated. So it is difficult to develop routine rules for sick people. But for normal people, and by definition 95 percent of healthy people are within normal limits, you can develop routine repetitive procedures. And that is the secret of the efficiency and economy of a programmed, systematized, multiphasic checkup.

An article in the Permanente newsletter Planning for Health touted the Multiphasic:

"A broad stride in the practice of Permanente’s fundamental principle of preventive medicine was accomplished with the recent inauguration of the Multiphasic Health Check-up program at the Oakland and San Francisco medical centers. A new type of general medical examination, the Multiphasic Check-up, is based on the premise that early diagnosis and adequate treatment can materially reduce the ill effects of significant diseases."

By the mid-1950s, 30 to 40 percent of all new members were choosing the multiphasic on their first visit.

However, in the early 1960s changes in technology would transform the examination. And the future was . . . computers.

Special thanks to ILWU archivist Robin Walker for her help with this article.