Kabat-Kaiser: Improving quality of life through rehabilitation

When polio epidemics erupted, pioneering treatments by Dr. Herman Kabat improved quality of life and care for patients nationwide.

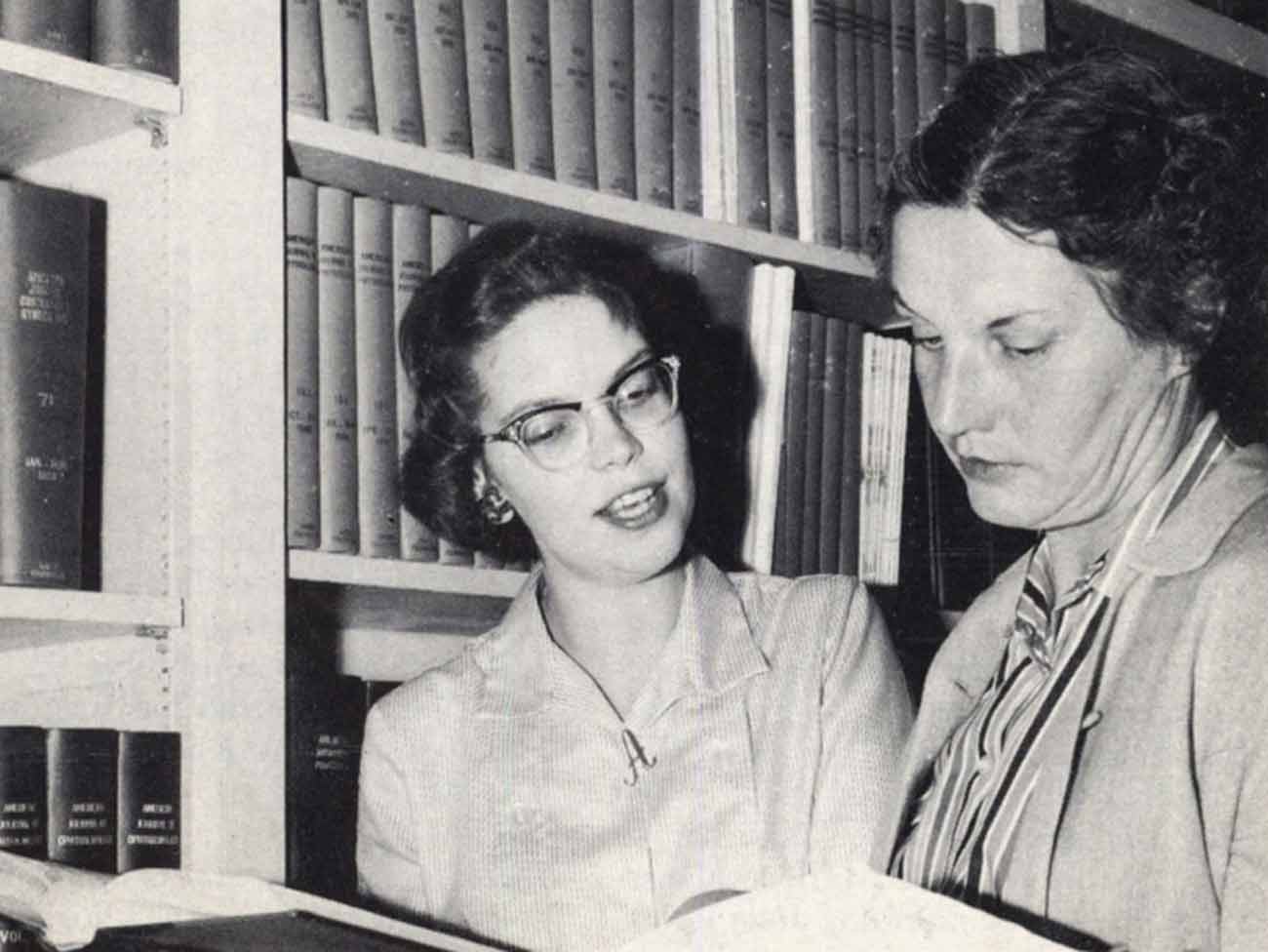

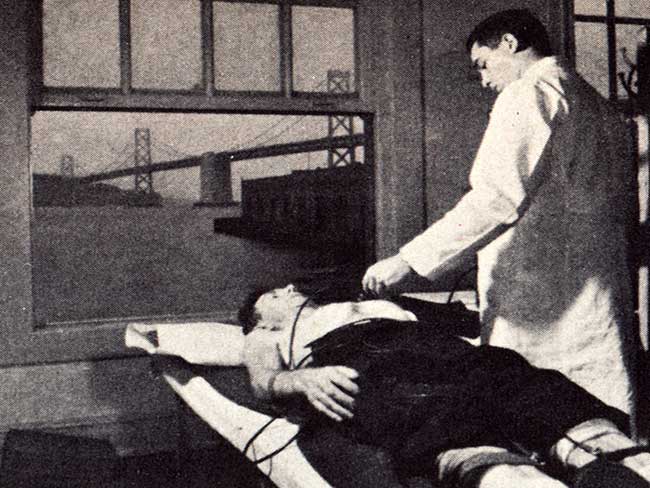

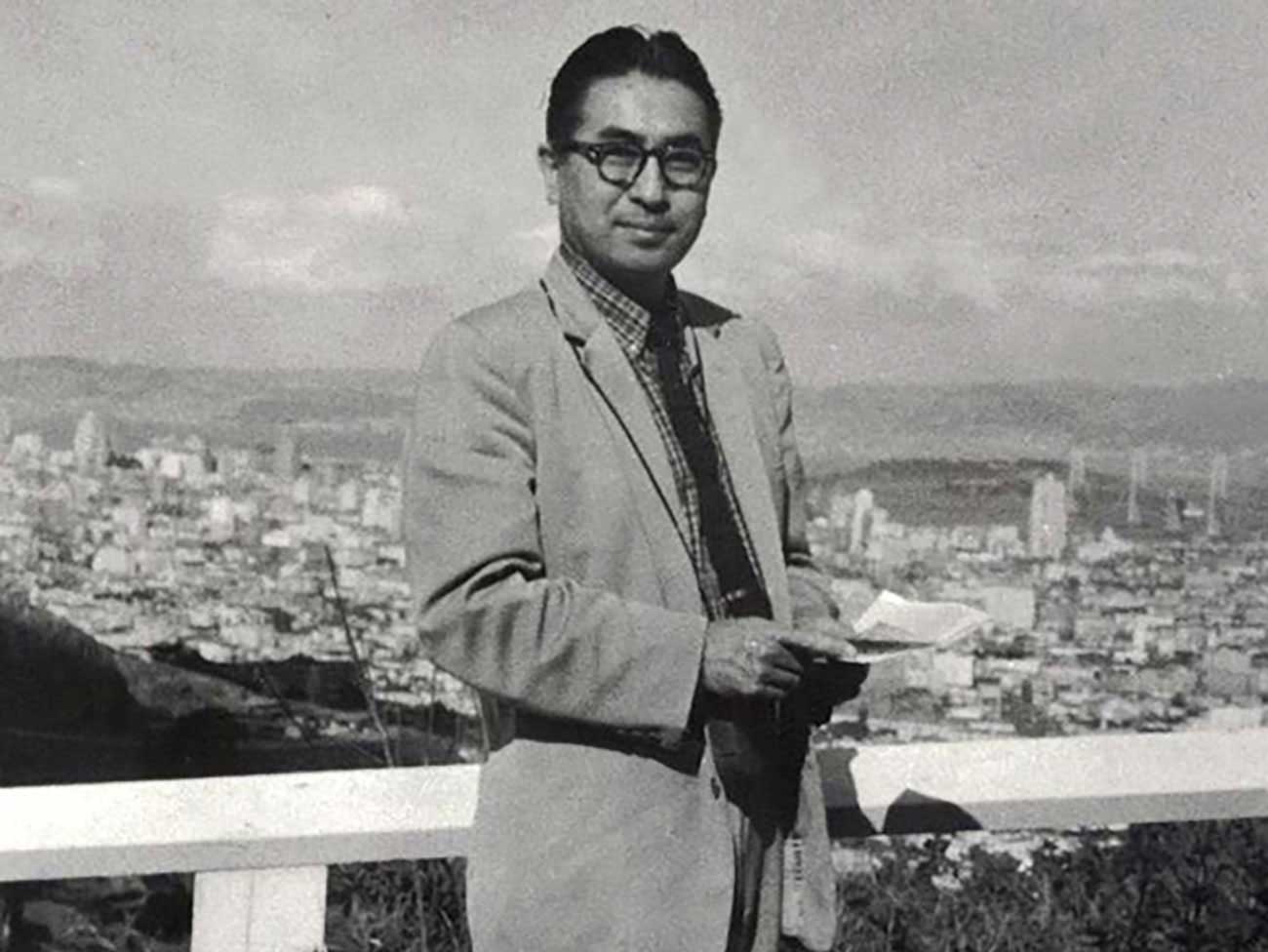

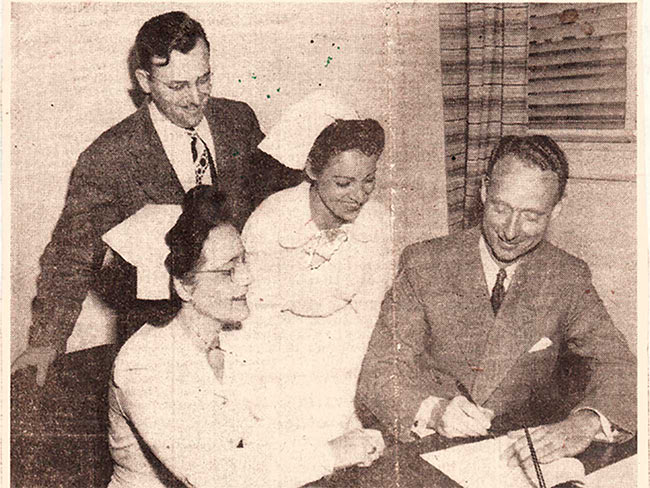

Kabat Kaiser Santa Monica, 1952, publicity photo with film and television actor Howard Keel.

Polio and multiple sclerosis. These disabling diseases of the nervous system posed daunting medical challenges as the Permanente Health Plan emerged from World War II and the nation looked toward an improved quality of life. Until a polio vaccine was developed in the mid-1950s, it was considered one of the most feared diseases in the United States, and MS is the most widespread disabling neurological condition affecting young adults in the world.

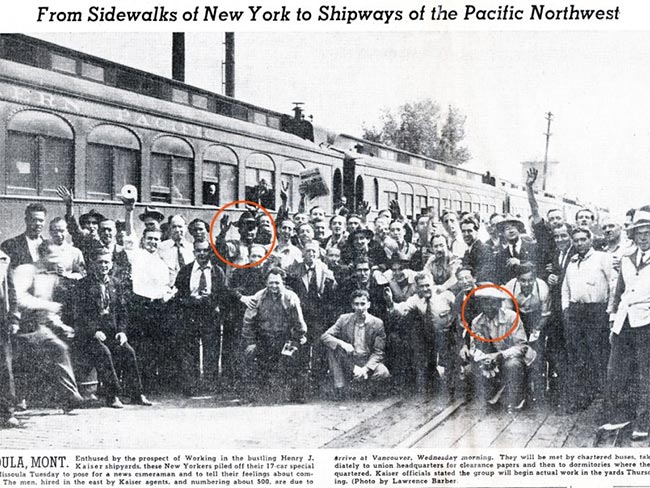

California’s first polio epidemic broke out in 1934 to 1935, with a second following in 1948. And, on a very personal note, Henry J. Kaiser’s youngest son Henry Junior (1917 to 1961) contracted MS in 1944.

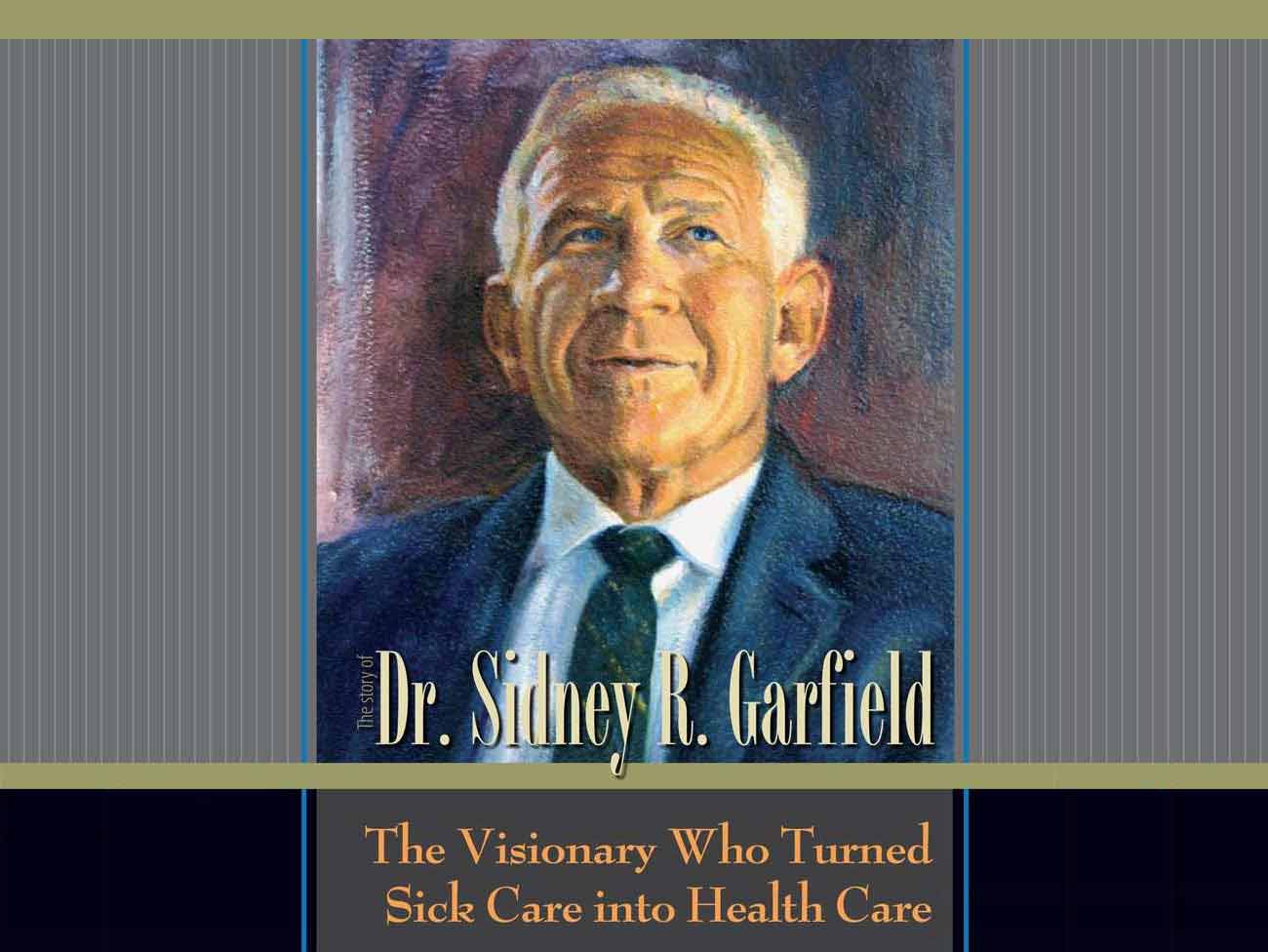

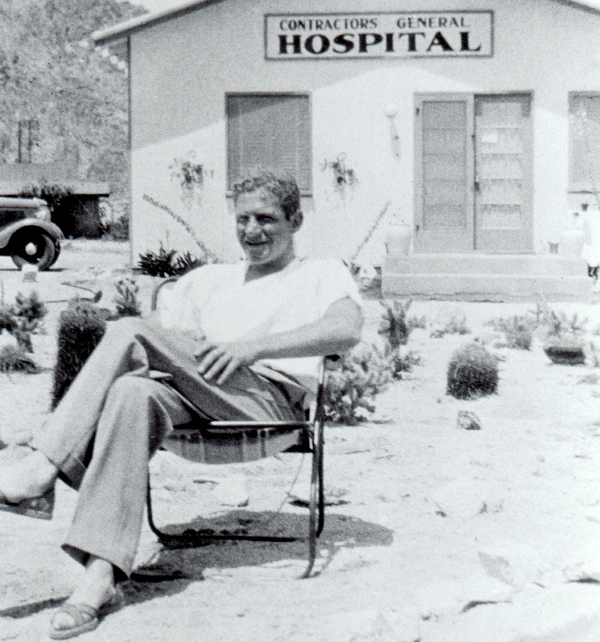

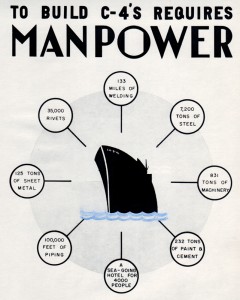

Henry J. Kaiser was determined to find the best therapy available, and through a 1946 Readers Digest article learned of Herman Kabat, MD, and his successful treatments. Kaiser sent Dr. Sidney Garfield, the founding physician of his successful World War II shipyard health plan, to assess the situation. Impressed with Dr. Kabat’s work, Dr. Garfield joined him to treat the younger Henry with considerable success. The rehabilitation program was deemed worthy of greater institutional support, and the Kabat-Kaiser Institute was born in Washington, D.C. (where Dr. Kabat practiced) in 1946. It was dedicated to “the restoration of the physically handicapped and to rehabilitate them to their optimum capacity, socially, economically, and physically.”

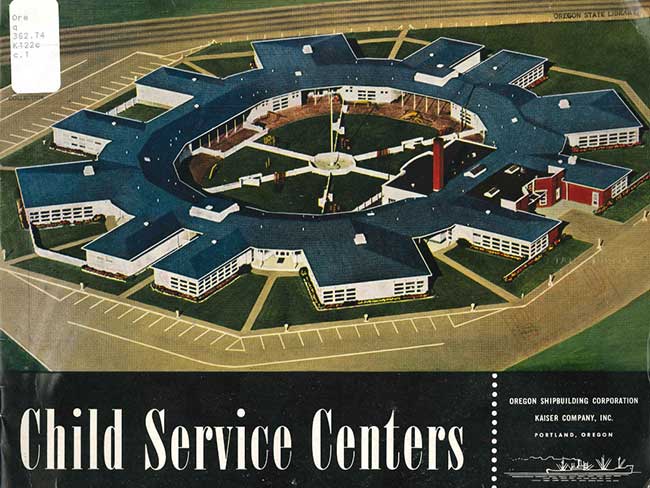

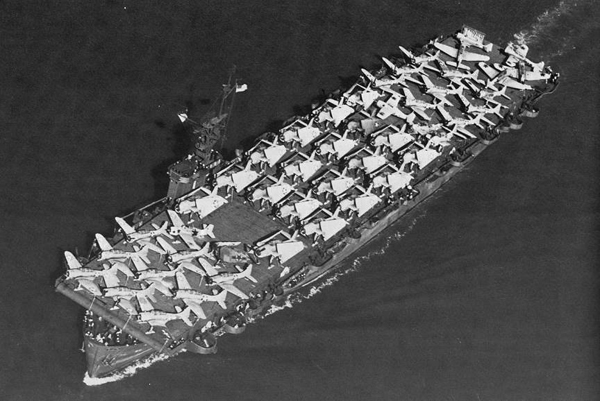

Eventually, there would be two centers in California, providing the largest non-governmental civilian rehabilitation program in the United States for patients with neurological disorders. The Washington facility was followed by one in Vallejo (August 1947) and a second in Santa Monica shortly thereafter. There was briefly a center connected to the Kaiser Oakland hospital, and the Washington facility was closed soon after 1950 when Dr. Kabat moved to Vallejo to direct the program.

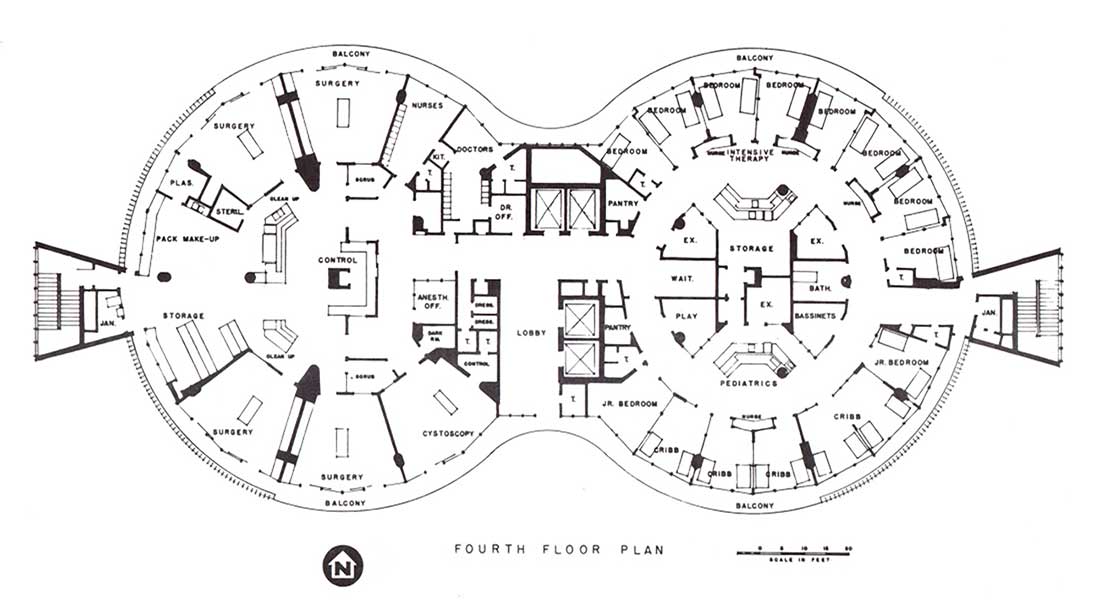

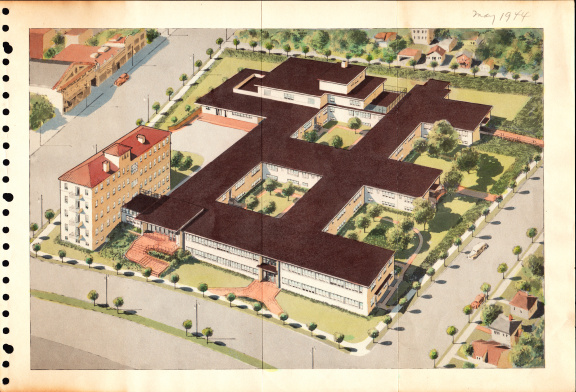

The Santa Monica facility started as the Edgewater Beach Hotel around 1925. In 1944 it was called the Ambassador Hotel and taken over by the Army Air Corps as a Redistribution Station to rotate men out of combat. After the war, it became a private club, but not for long. The Permanente Foundation bought the building in October 1948 and opened it the next month as the Kabat-Kaiser Institute. A hospital ward was added in January 1949.

A news account from 1952 described the setting:

"First impression on entering the Santa Monica Institute is that of stepping into a luxurious beach resort. A large swimming pool, beautifully furnished lounge, and inviting glassed-in beach-front patio are located on the ground floor. Shorts, pedal pushers, swimsuits, and jeans are the principal attire. The second impression hits one like an avalanche. Every person in sight is either in a wheelchair, walking with crutches or body braces; or being pushed along on a gurney. Everyone appears happy and busy, going to or from a water therapy room, a physiotherapy section, or an exercise room.

"Many volunteer welfare and social organizations contribute to the entertainment and special needs of the patients. Recreation includes nightly programs of moving pictures, “wheel-chair” square dances, bingo, water volleyball, or variety shows."

Given the center’s proximity to Hollywood, it was often the site of cameo appearances by movie stars. But that relationship took a deeper step when the actress Ida Lupino directed (and co-wrote, and co-produced) a film there. Never Fear (1949, also titled The Young Lovers), a story about a beautiful young dancer with a promising career who contracted polio and struggled to recover, had personal meaning for Lupino, who had contracted polio herself in 1934. Lupino made the film to combat the public fear of polio during the 1948-49 epidemic, and captured the power of the center’s program using actual patients and, yes, a wheelchair dance.

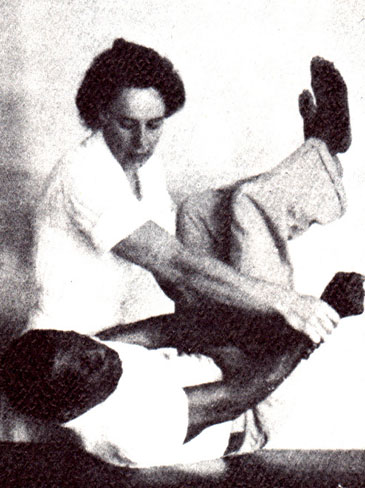

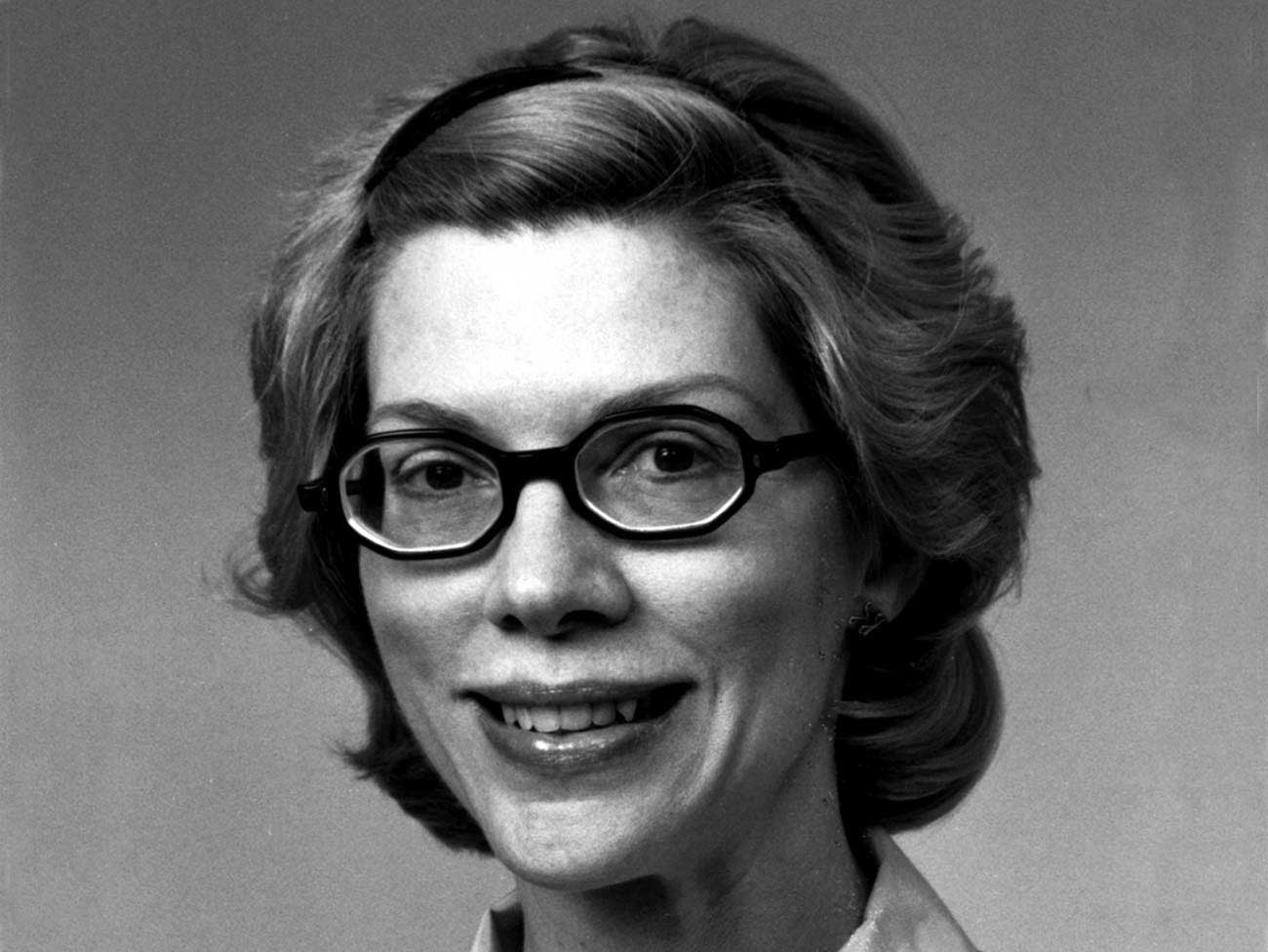

The centers were busy; in 1950 the D.C. center was treating almost 200 patients, Vallejo saw over 400, and Santa Monica served almost 600. The staff at Santa Monica included over 60 therapists, psychologists, and consulting physicians. Margaret “Maggie” Knott was the exceptional lead physical therapist who became world famous, along with Herman Kabat, for developing, practicing, and teaching the technique of “proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation.” PNF is a form of flexibility therapy that involves stretching and contracting targeted muscle groups.

Joel Bryan (1937-2005) was the Founder and Director of Disabled Students’ Services at UC Riverside and UC Davis. He was also a patient at Kabat-Kaiser Santa Monica from 1951 to 1954, and recalled his treatment in a 2000 interview:

"Three months after I arrived there I could get up in a wheelchair for the first time. My spine was fused later, which straightened out my very significant scoliosis. I was 5′4″ when I got polio, and by the time I was 16 or 17, I was 6′2″ or 6′3″ - stretched out. There’s a lot of growing that occurs, and my back just wouldn’t support it. Those things got straightened out. I wound up with the use of my fingers on my right hand and the bicep on my left arm."

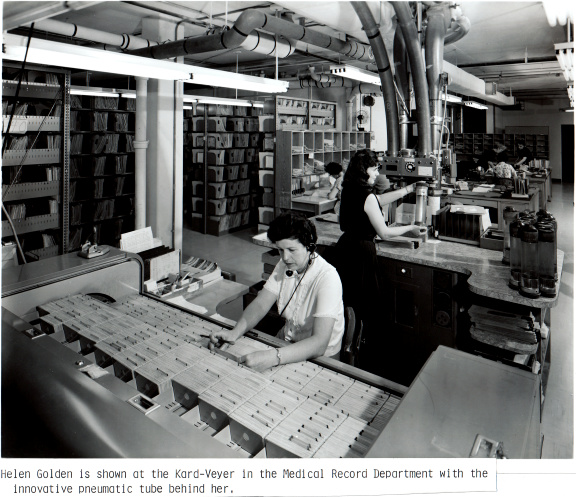

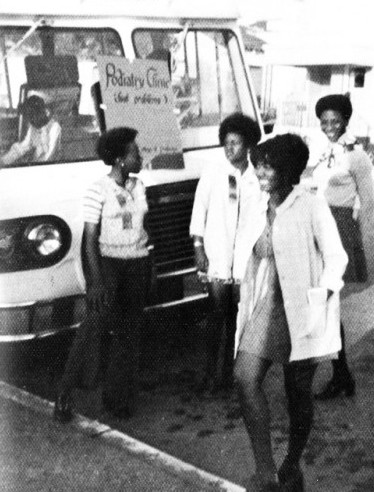

Station wagon for transporting patients to recreational activities donated to Kabat-Kaiser Institute in Santa Monica by the Federation of Women’s Telephone Workers of Southern California, 1952. Standing left is Raymond T. McHugh, K-K administrator, next to Mary V. Marsteller, president of the FWTWSC.

In 1955, Dr. Kabat left the organization. The Kaiser Foundation Hospitals assumed complete control and renamed the two facilities the California Rehabilitation Centers. In 1962 the name was changed to Kaiser Foundation Rehabilitation Center to avoid confusion with state institutions with a similar name.

Santa Monica’s rehabilitation portion closed in 1962, the convalescent facility remained open until patients could be reassigned, and the site was demolished in 1964. The Kaiser Foundation Rehabilitation Center and Hospital in Vallejo continues to this day.