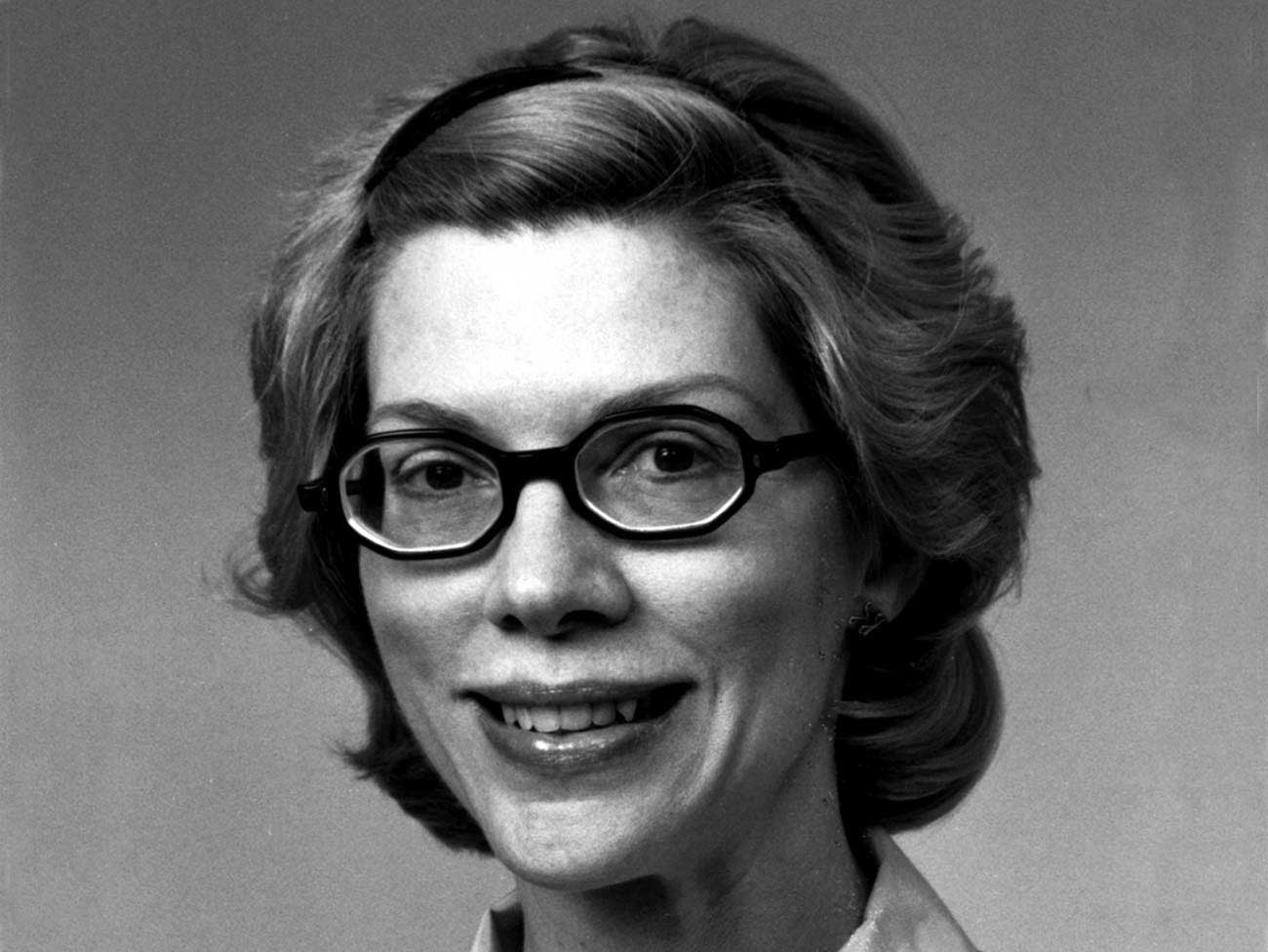

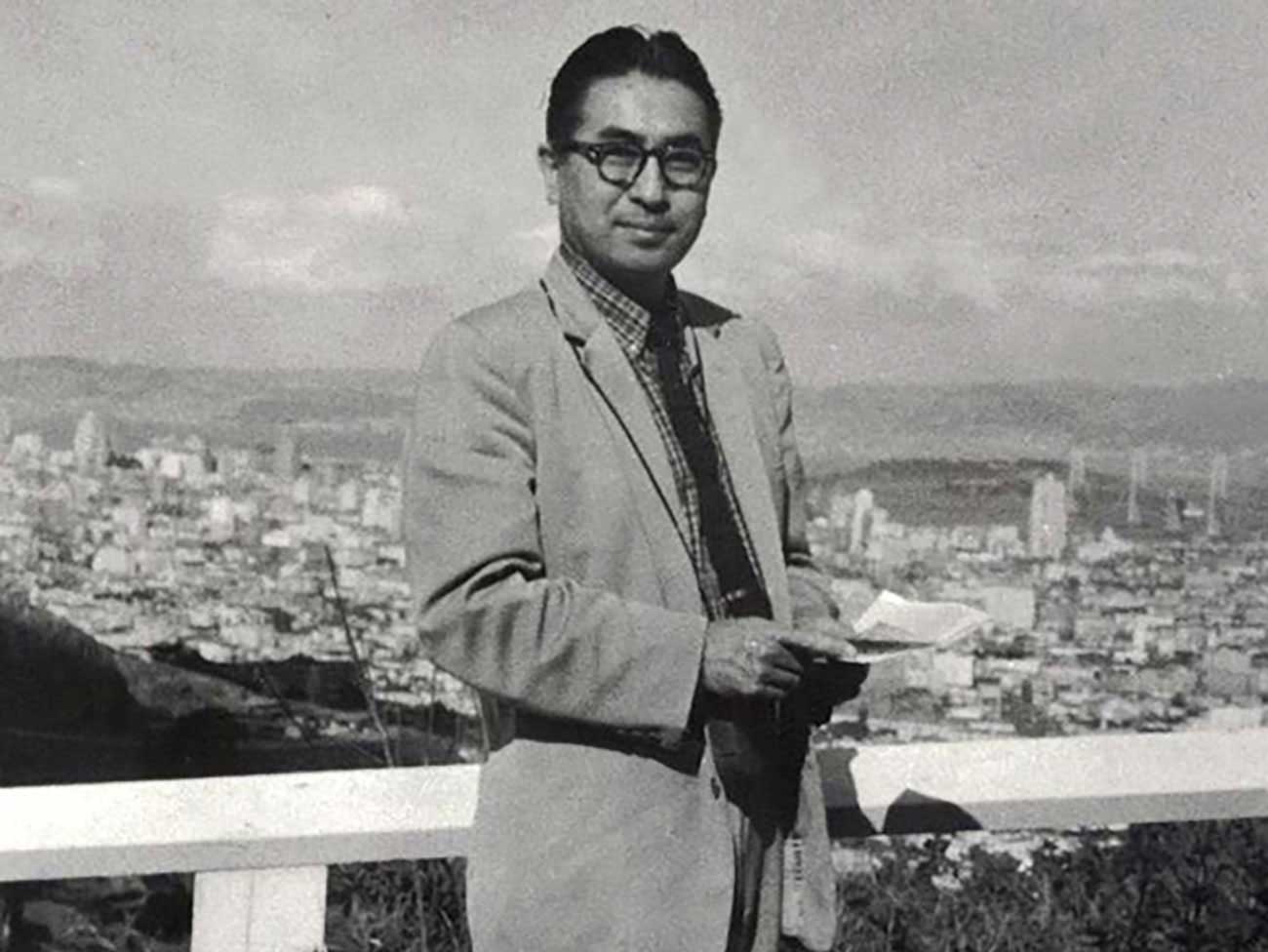

Early Permanente physician leader views health care future from 1966 vantage

Dr. Cecil Cutting, executive director of The Permanente Medical Group from 1957 to 1976, reflects on Kaiser Permanente's impact and future of health care.

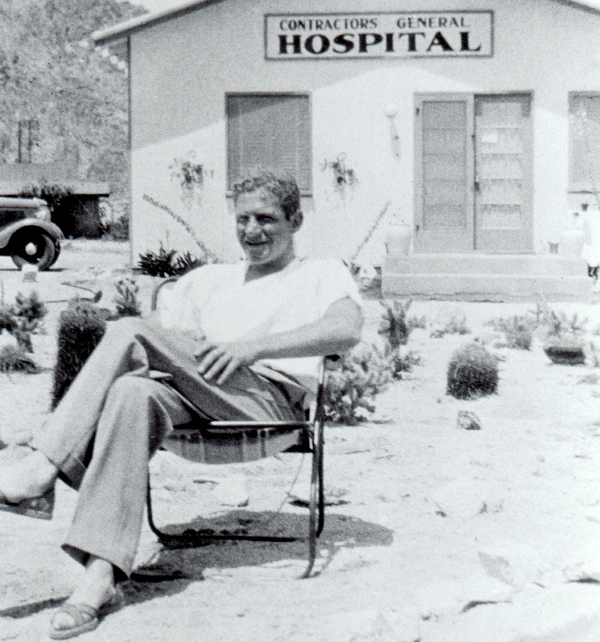

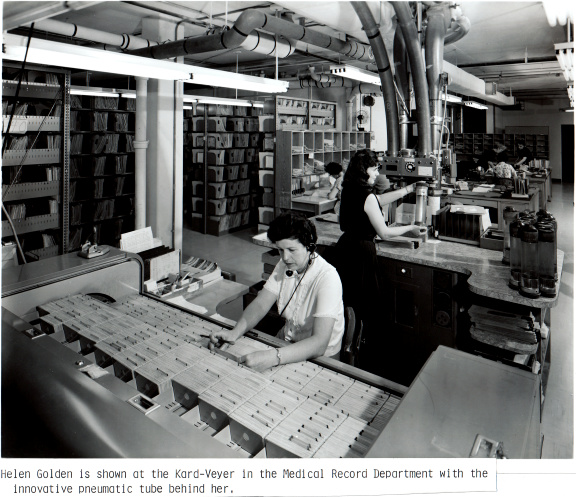

Cecil Cutting, MD, led The Permanente Medical Group from 1957 until 1976. Kaiser Permanente archives photo

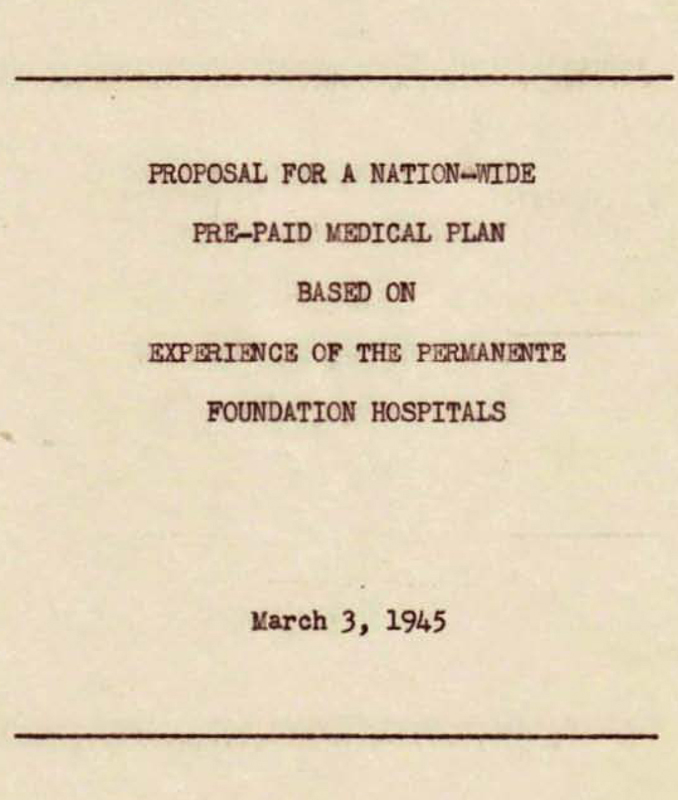

As we wonder and worry about the fate of health care in America, it’s interesting to look back at how Kaiser Permanente physician leaders saw the future just after the 20-year-old health plan got a firm foothold in the 1960s.

Cecil Cutting, MD, executive director of The Permanente Medical Group, told of his worst fears in a talk to a group of hospital administration graduate students at the University of Chicago on Nov. 17, 1966.

“Looking ahead, there seems little doubt but that our present ‘derangement’ of providing medical care is totally inadequate to absorb the onrush of the technological revolution that is now upon us, even if the rising personnel costs can be absorbed,” Cutting lamented.

“The tempo of the hospital has changed from a relatively easy-going, low cost charity institution to a competitive, high cost one, with third parties paying the costs and becoming ever more critical of hospital management,” Cutting said.

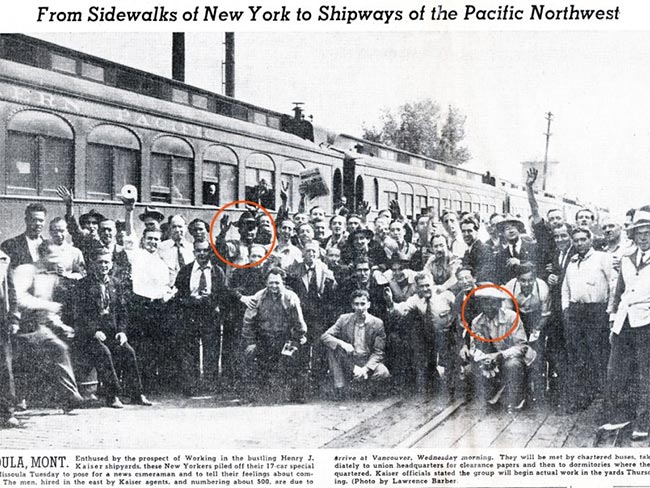

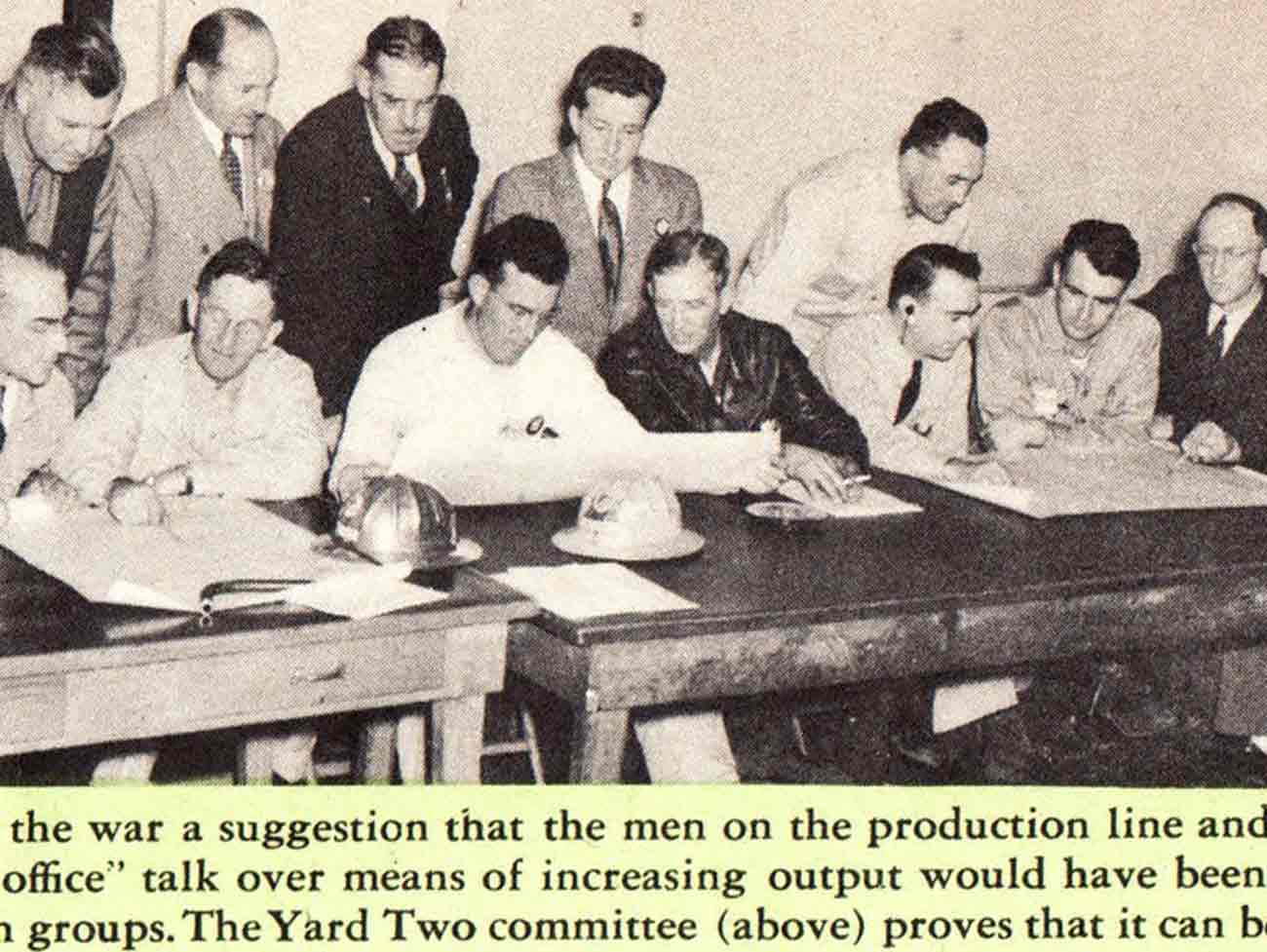

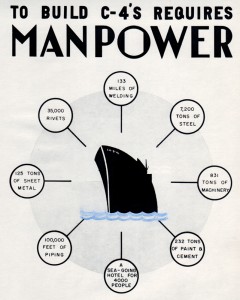

A 1935 Stanford Medical School alumnus, Cutting joined Sidney Garfield when he established a medical care program at the Grand Coulee Dam job site in the late 1930s. During the war, Cutting also took a leading role in Garfield's Kaiser wartime shipyard program in Richmond, California.

1960s changes threatened traditional medical care delivery

Cutting was talking about the mid-1960s climate that included newly enacted government-paid Medicare-Medicaid programs for the elderly and poor, a flood of new medical technology, health care professionals’ demands for higher pay, and a proliferation of union and company health plans for workers.

With the blessing of Kaiser Permanente founding physician Sidney Garfield, Cutting laid out the problem: “Today we have many individual, unrelated, competitive hospitals seldom organized among themselves as a team, for the most part with unorganized staffs of physicians, serving an unknown population — a population unknown both in numbers and in health requirements.

“The consequences of continuing along our present path of complete disorganization are staggering and make the need to change methods of organizing medical care inevitable,” he told the group.

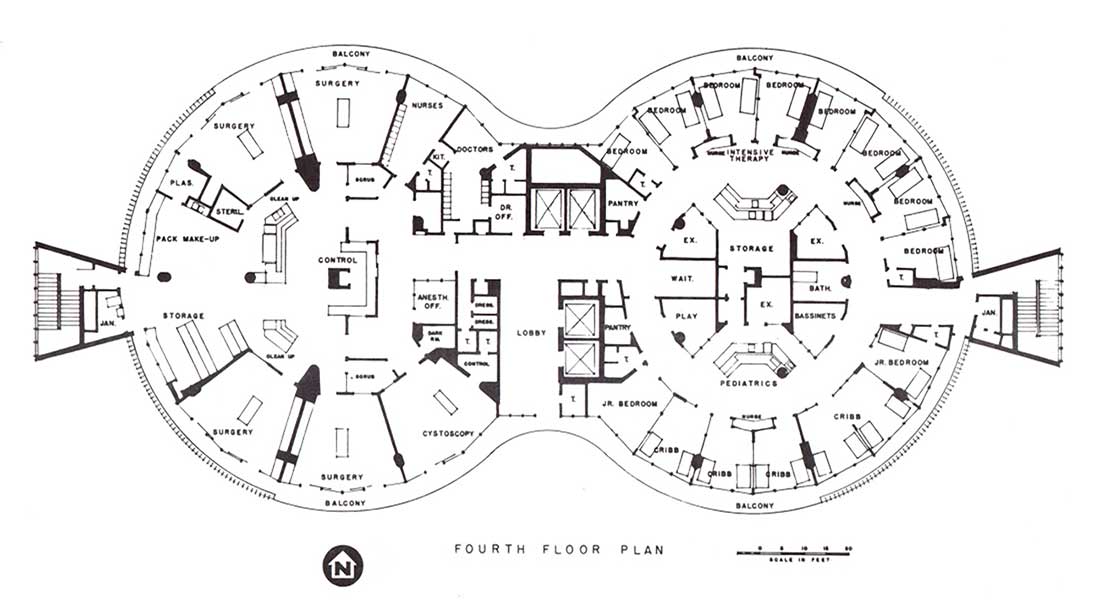

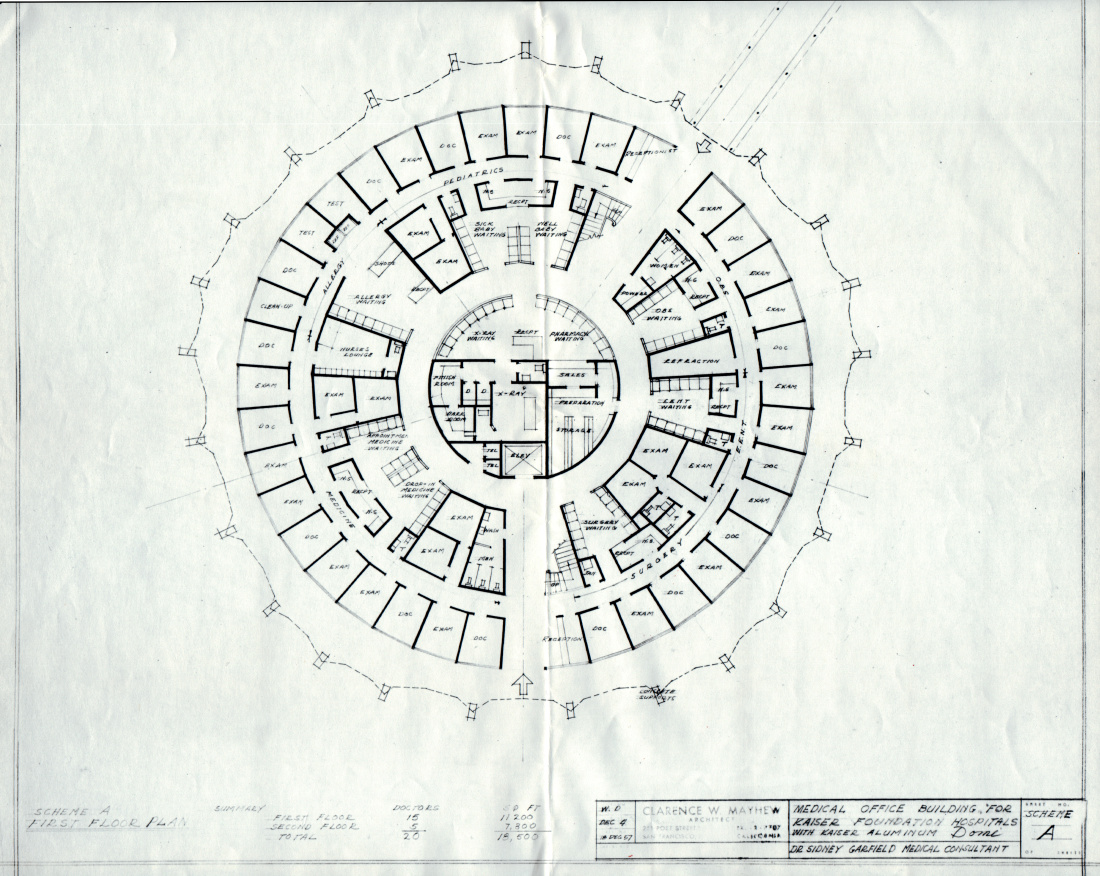

Cutting warned that high technology was too expensive for an individual institution to purchase on its own. He said a system should be established in which medical facilities are designated as one of three types: a community preventive health center; a service hospital for routine care, such as trauma, appendectomy, hysterectomy, maternity, hernias, cancer surgery, pediatrics and psychiatry; and a “super-specialty” hospital.

‘Super-specialty’ hospital to optimize high technology use

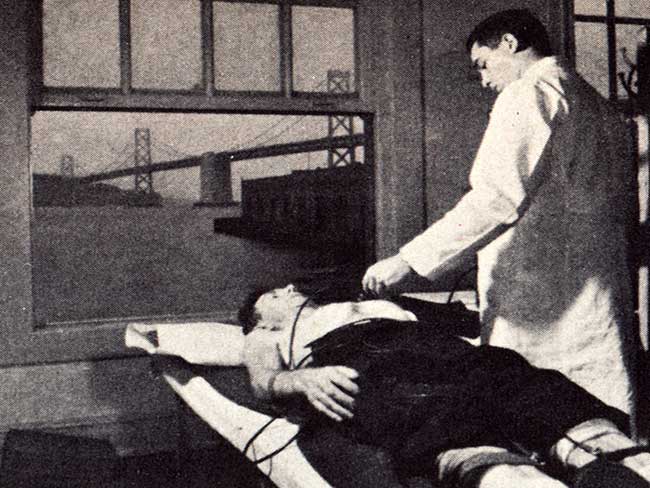

The highly specialized treatment facility envisioned by Cutting (perhaps the precursor of a center of excellence) would be designed for handling neurological cases, open-heart surgery, megavoltage radiotherapy — the types of cases that required the most sophisticated equipment.

Here, specialists would take care of a sufficient number of patients referred from other facilities to optimize utilization of the equipment and highly skilled staff.

As it happened, Kaiser Permanente was in the process of developing such a system by this time, and Cutting could report its success to his audience. “In Northern California area the Kaiser Permanente program is working along these lines, though it is by no means a finished demonstration,” Cutting said.

“The (Kaiser Permanente) group practice-prepayment arrangement is, in itself, a step toward improving organization of medical care and undoubtedly makes accomplishment of further organization considerably easier to attain.”

Health center concept proposed

The health center concept, which Cutting called “predictive and preventive medicine,” had already been developed and was in operation in Kaiser Permanente Northern California. “Forty thousand patients a year are being given an extensive health questionnaire (to complete), updated each year, and an automated battery of some 20 test measurements plus 18 laboratory procedures amounting to almost 1,000 different characteristics on each patient,” Cutting continued.

With this information, all recorded in a computer data base, Kaiser Permanente physicians compiled knowledge of each patient’s changes from year to year. This information helped physicians to predict illness and to advise patients and their families about how to prevent chronic illnesses such as diabetes, heart disease and cancer.

Data compiled about whole populations, i.e., Kaiser Permanente members, also helped researchers answer such questions as: Can treatment of asymptomatic patients with a slight increase in blood sugar prevent diabetes altogether or merely postpone the disease? With data from a questionnaire about a patient’s psychological state, researchers compared the effectiveness of psychiatric services versus medical office visits for reducing total visits for emotionally disturbed patients.

Too many specialists spoil the broth

Cutting complained to his audience that medical schools were turning out too many specialists, a trend that threatened basic medical care. “It would appear that the rush for super-specialization may be leaving behind an ever widening gap in well rounded, competent medical judgment.

“Though the individual episode of care may be superb, it certainly does little for the orderly development of efficient, economical medical care as a whole.”

In what must have surprised many, Cutting suggested that medical education should develop a new type of medical doctor: the preventive, predictive specialist. “Following the natural development of disease of entire families over long periods, alerted to early changes through the screening program, he becomes a health specialist.”

Today, both primary care and preventive medicine are specialties recognized by the American Board of Specialties.

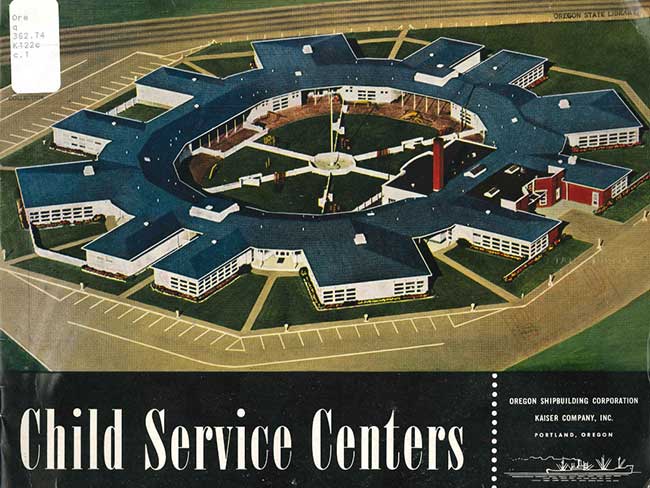

Kaiser Permanente has advanced Garfield and Cutting’s ideas about preventive care and health appraisals in a variety of ways over the decades. Kaiser Permanente physicians promoted healthy eating and exercise for the workers in the World War II Kaiser Shipyards, and they began offering preventive testing in the 1950s for members of the longshoremen union and other groups.

Kaiser Permanente’s ‘Total Health’ concept emerges

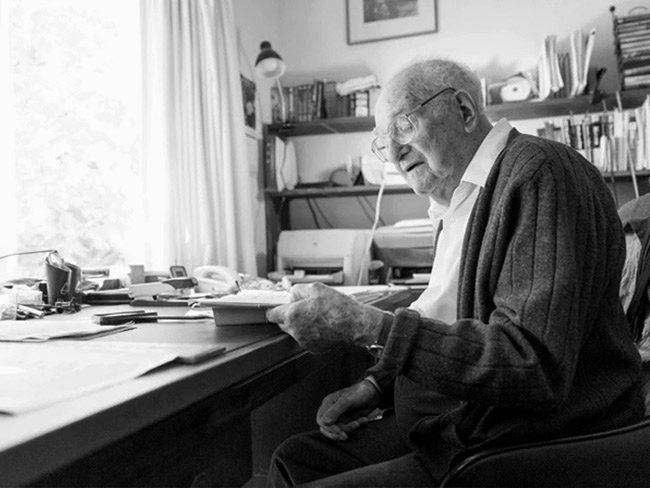

In the 1970s, health education centers were established to teach patients how to stay well; Garfield’s Total Health Research Project launched in the 1980s led to the opening of special centers where healthy patients received their routine care.

A pilot Health Education Center opened in Oakland in 1967. Sidney Garfield, MD, champion of Total Health, stands next to the transparent woman, one of the center’s displays.

Centers for preventive medicine functioned within Kaiser Permanente for many years, largely giving way to periodic screenings for particular diseases such as breast and colon cancer, heart disease, hypertension, and diabetes. Healthy Living programs, an expansion of member health education, have flourished in the past decade offering many classes in good nutrition, exercise, smoking cessation, and stress reduction.

Cutting ended his talk with a few wishes for the future: community institutes to teach people to preserve their good health, easily shared electronic medical records, and above all, cooperation among health organizations to provide a broad spectrum of care — from the preventive to the most complicated.

“When (all) care, whether in super-specialty hospitals, service hospitals, extended care, office or home, is correlated ... I will begin to see hope,” he said.