Maternity care evolves to embrace family

Shortened in the 1970s led Kaiser Permanente to offer prenatal classes and encouraged father participation in a family-centered care program when hospital stays.

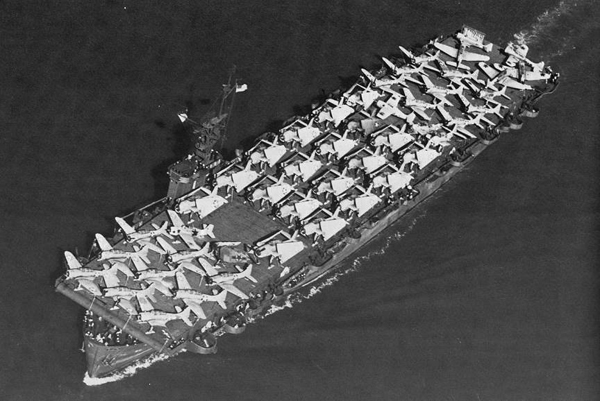

Kaiser Permanente provides tools to help smooth a new mother's transition to home. Photo originally published in the Permanente Journal, Fall 2005.

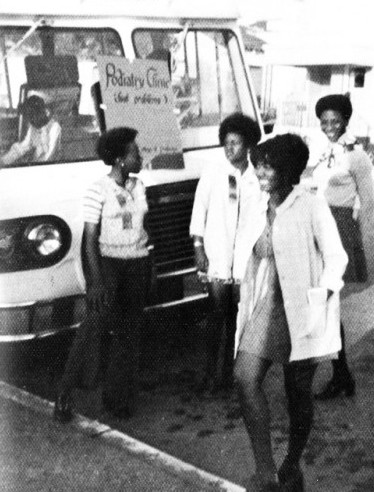

1978 American Journal of Nursing article authored by Kaiser Permanente's maternity coordinator, Deloras Jones, RN, BSN.

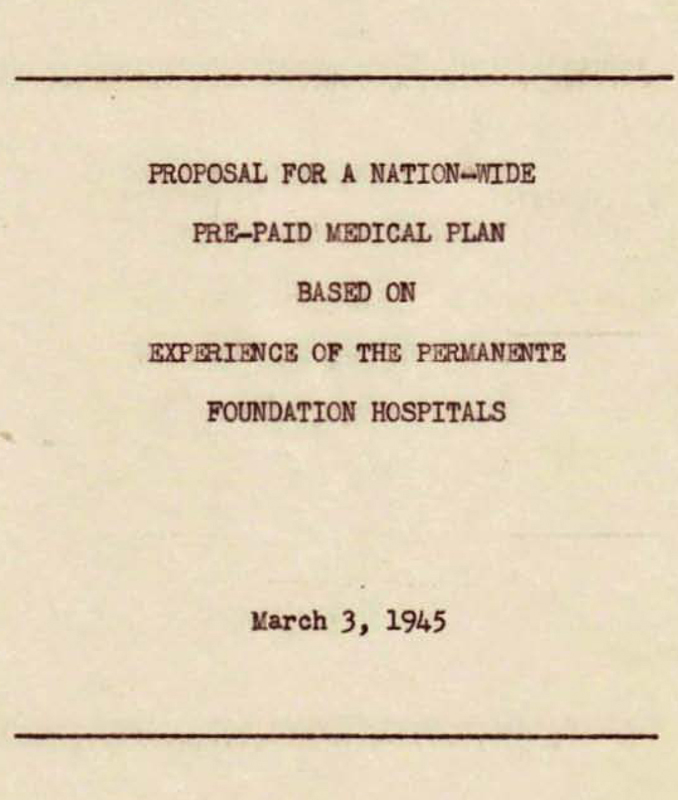

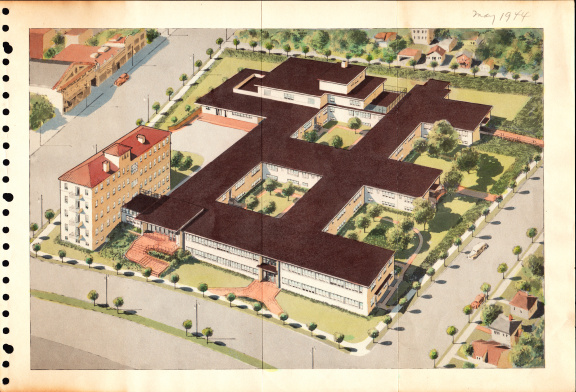

In the 1970s, Kaiser Permanente responded to the rising influence of feminism and a popular trend calling for home births, drug-free deliveries, and family participation by establishing the Family-Centered Perinatal Care Program at the San Francisco Medical Center.

With patients demanding a more natural birthing experience, the Kaiser Permanente family-centered birth program zeroed in on one particular aspect of the trend: Shortening the mother and infant’s postpartum stay in the hospital. Deloras Jones, RN, BSN, maternity coordinator for Kaiser Permanente San Francisco, began recruiting participants in 1973 and found many expectant parents were enthusiastic.

“The parents wanted increased father involvement, less family separation after birth, and treatment of mother and infant as though they were well, not ill,” Jones wrote in “Home After Delivery,” a 1978 article in the “American Journal of Nursing,” after 1,200 families had used the program successfully.

In the decades after World War II, the length of stay standard for childbirth had risen to as many as 10 days, keeping mothers away from their families and in the sterile environs of the acute care hospital. A picture in a KP newsletter from the late 1940s shows a new mother preparing to leave the hospital after 10 days of rest and recovery.

Patient education key in shortening hospital stay

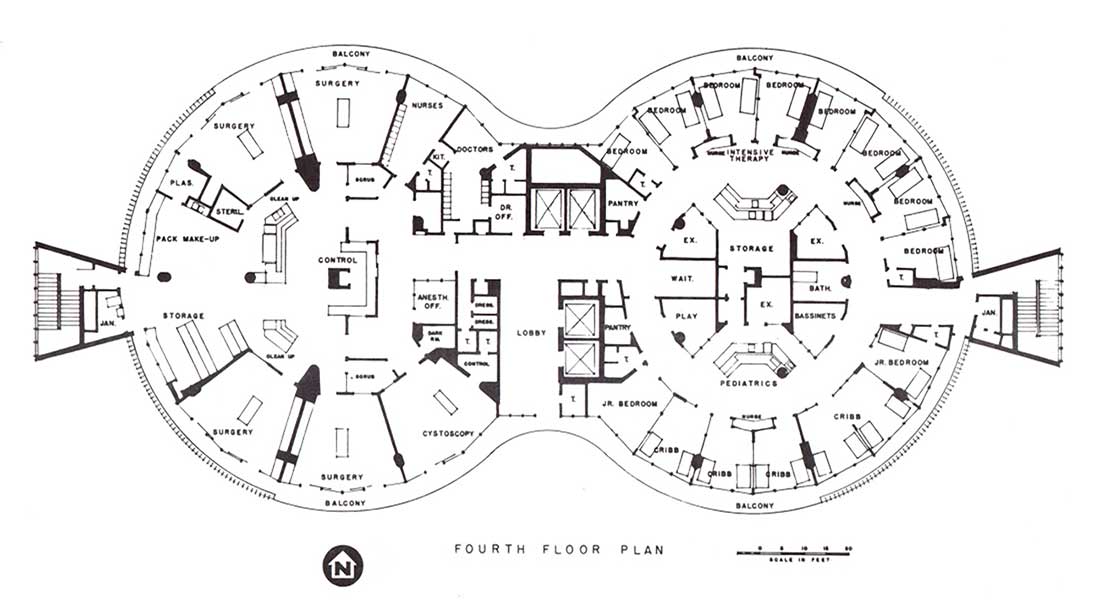

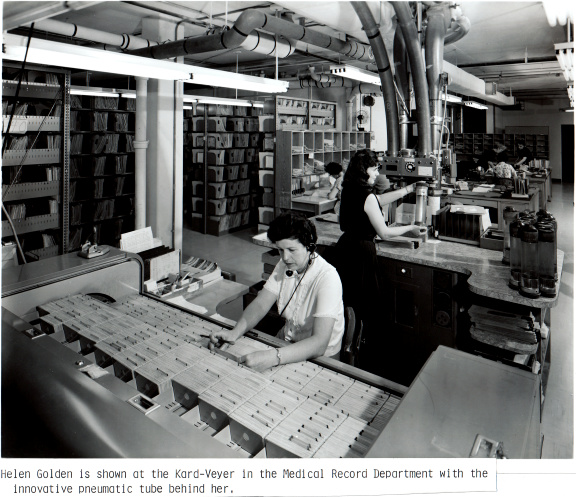

As an essential part of the 1970s shortened-stay program, KP began to offer prenatal classes and encouraged the father’s participation in childbirth preparation as well as in labor and delivery. The hospital experience included rooming-in for mother and infant after 24 hours of observation in the nursery, breastfeeding training, and infant care classes.

With an eye to shortening stay, the program focused on protocols for assessing mother and baby’s health and ability to go home within 12 to 24 hours. A nurse was assigned to visit the family at home for 3 days and to be available for questions and assistance for up to 2 weeks.

In 1976, Jones and colleagues Mark J. Yanover, MD, and Michael D. Miller, MD, published a report of their study of the experience in the San Francisco family-centered program. They compared a group of 44 low-risk mothers who delivered their babies along the typical routine with 44 others who elected the early discharge program. The researchers concluded that “this method of perinatal care is as safe as that traditionally provided at our medical center.”

FAMCAP had a major influence over early discharge standards developed for both the American College of Gynecology and the American Association of Pediatricians and marked an acceleration of a trend toward shorter hospital stays for postpartum mothers.

The shorter stay phenomenon in the 1970s was wholly embraced by cost-conscious health maintenance organizations, often without the follow-up care that was the hallmark of the Kaiser Permanente approach — and became the source of intense national debate in the 1990s.

Are shortened stays too short?

According to figures that came out in Congressional hearings, the median length of stay for postpartum women across the U.S. had dropped almost 50% between 1970 and 1992 — from 4 days to less than 2 days for a vaginal delivery. “Within the last 3 years, stays have declined from 48 hours to 24 hours. Some (women) were even required to leave the hospital in as little as 8 hours after delivery,” according to Debra Kuper writing in the “Marquette Law Review” in 1997.

There were increasing reports of kernicterus, a rare and preventable complication of jaundice, and mental retardation due to the failure of postpartum mothers to return for Phenylketonuria testing, amongst other tales of women being kicked out of hospitals before adequate assessment of their or their infants’ readiness to go it alone.

In response, Congress enacted the Newborns’ and Mothers’ Health Protection Act of 1996 to mandate 48-hour stays for vaginal births and 96-hour stays for cesarean births unless the mother and physician agree to a shorter stay. Both the national OB-GYN and pediatrician associations revised their standards to reflect the new mandates.

Nonetheless, shorter hospital stays with more choice and control over the childbirth experience have become the norm for parents across the country. Expectant Kaiser mothers and fathers are now given a birth plan to fill out that allows them to select the delivery room environment, methods of inducing labor and controlling pain, delivery position, and various postpartum procedures.

Recent national trends show the cesarean section rate for first-time low-risk mothers climbing — California rates increased from 20% to 26.5% from 2000 to 2005. Statistics also show a retreat from the 1980s surge in women wanting vaginal deliveries after cesareans with California rates for repeat cesareans up from 84.4% to 94.3% from 2000 to 2005.

Kaiser Permanente continues to support women who want to deliver vaginally after they’ve had a C-section and offers programs and procedures that encourage strong mother-baby bonding practices, including breastfeeding. Today, about 75% of American new mothers nurse their newborns.

Honors for KP “baby-friendly” hospitals

Kaiser Permanente Southern and Northern California regions were honored in 2008 by the California Breastfeeding Coalition for leadership in supporting nursing mothers while medical centers in Clackamas, Oregon; Honolulu; and Hayward and Riverside, California, were all been named “baby-friendly hospitals” by the Baby-Friendly Initiative of the World Health Organization.

Keeping birth “normal” is still a worthy goal for the organization, Fontana midwife and nurse specialist Iona Brunt wrote in 2005 in “The Permanente Journal.”

“We must empower mothers with the belief that their bodies are made to give birth and, in most circumstances, will do well. We must dissipate the idea that without our high-technology intervention, babies cannot be born healthy and safe.”

“It makes sense,” she said. “It’s cost-effective and it’s the right thing to do.”