It’s time to address America’s Black maternal health crisis

Health care leaders and policymakers should each play their part to help eliminate health disparities.

Improving care quality and access can help improve health outcomes for Black mothers.

Black women are almost 3 times more likely to die due to a pregnancy-related cause than white women. That increased risk exists regardless of education or income level. Black mothers are also twice as likely to experience severe complications during pregnancy.

The reasons for these disparities are multifaceted. Their underlying cause is centuries of racism affecting the conditions where people are born, live, work, and age.

Our policymakers and institutions can’t quickly or easily solve these problems. But health care leaders and policymakers can take more immediate steps to improve Black maternal health.

Challenges to Black maternal health

Many factors contribute to the Black maternal health crisis. Among them are:

- Lower quality care: Research shows Black patients receive lower-quality health care than white patients. Bias against Black patients coupled with structural racism means some expectant Black patients are more likely to have their pain and concerns ignored. They have a 53% increased risk of dying in the hospital, regardless of their income level or insurance status.

- Insurance status: Black people are almost twice as likely to be uninsured as white people. They have greater difficulty getting the care they need. This is especially problematic during pregnancy when regular care can help keep mother and baby healthy.

- Unmet social health needs: Black women are more likely to have unmet social health needs such as food, housing, and transportation, compared to white women and men. This can impact Black peoples’ health and prevent them from accessing care. For example, Black parents may rely on public transportation to get to their prenatal appointments. If the city stops offering bus service in their neighborhood, their health and the baby’s health suffer when they cannot attend their doctor appointments.

Improving care for pregnant Black people

Two ways health care organizations can take immediate action to improve Black maternal health is by focusing on care quality and making care access more equitable.

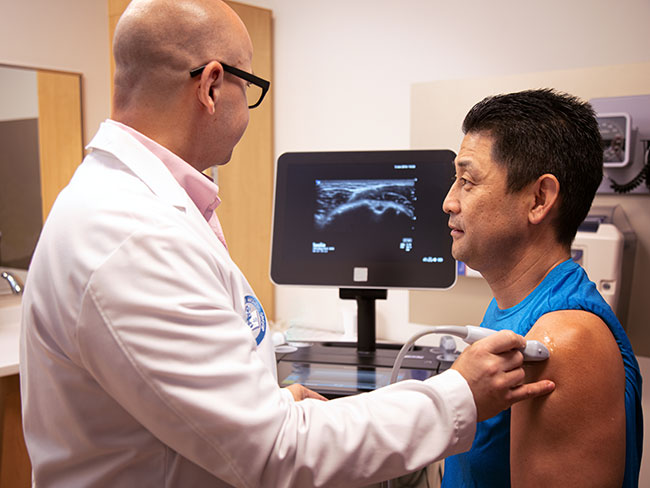

An example is Kaiser Permanente’s obstetric hypertension program. The program is for patients diagnosed with or at risk of developing high blood pressure, also called hypertension.

Hypertension is a leading cause of death during and after pregnancy. It impacts Black mothers during pregnancy at much higher rates than white mothers.

Here’s how our obstetric hypertension program works:

- Patients in the program go to their regular in-person prenatal visits. But they also get more frequent blood pressure monitoring and care check-ins, often through remote patient monitoring using phone and video visits.

- Patients get a Bluetooth-enabled blood pressure monitor to use at home. They learn when and how to take their blood pressure. The readings they take get sent to their electronic health record.

- Patients are notified if they have a high blood pressure reading. Their doctor lets them know whether to take their blood pressure again or seek care.

- The patient’s care team tracks the patient’s readings in their electronic health record. This way, the doctor can adjust the patient’s blood pressure medication if needed. Or, the doctor may even recommend delivering the baby early, if the patient’s risk is high.

Home-based monitoring is especially helpful for patients who can’t find reliable transportation to the doctor. This is a challenge Black patients confront more often than white patients.

The obstetric hypertension program was first offered in 2019 by our Kaiser Permanente team in Georgia. We’re expanding it to everywhere we provide care.

When the Georgia team piloted the program, it included 736 pregnant patients — the majority were Black. Of those patients, 36 had their labor induced due to their high blood pressure.

If our care teams had not monitored these patients carefully, they would have been at higher risk for dangerous complications including seizures, bleeding, and strokes.

Our obstetric hypertension program and other care quality and access initiatives show promise to keep at-risk pregnant and postpartum populations safer and to avoid potentially deadly complications. They are important strategies health care leaders can use to improve Black maternal health.

Policymakers’ role

Meanwhile, policymakers should address the issues of insurance coverage, care access, and support for social health needs.

Policymakers should:

- Expand Medicaid coverage. Everyone who’s uninsured struggles to get care. Black Americans are more likely than white Americans to not have insurance. People who have Medicaid during pregnancy often lose their coverage shortly after childbirth. Many deaths occur during this time. State policymakers should support the extension of Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program coverage to 12 months after childbirth. Policymakers should also streamline enrollment and extend enhanced tax credits for people buying coverage through the health insurance marketplace. This will help families afford coverage.

- Improve access to telehealth and virtual care. As our experience at Kaiser Permanente shows, telehealth and virtual care (such as remote patient monitoring) can be a lifeline for pregnant people who don’t have reliable transportation or who can’t take time away from their responsibilities to go to the doctor. Kaiser Permanente urges the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation to establish a demonstration project, which is a way the federal government can test new models of health care payment and delivery. The project should assess whether providing phone and video visits during and after pregnancy reduces racial differences in health outcomes. Policymakers should also continue to fund broadband expansion to both unserved and underserved populations. They should subsidize the cost of internet and device access for people with low incomes.

- Address unmet social health needs. Policymakers should support policies that address unmet social health needs among pregnant people. Black people are less likely to have stable housing, nutritious food, or reliable transportation than white people. Legislative proposals, such as the Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act, would direct more resources toward these needs. It would also support community-based organizations working to promote health during pregnancy and help grow and diversify the workforce caring for pregnant people.

There are clear ways that health care organizations and policymakers can work together to improve Black maternal health. It is imperative we take action.