Kaiser Permanente begins its post-World War II life

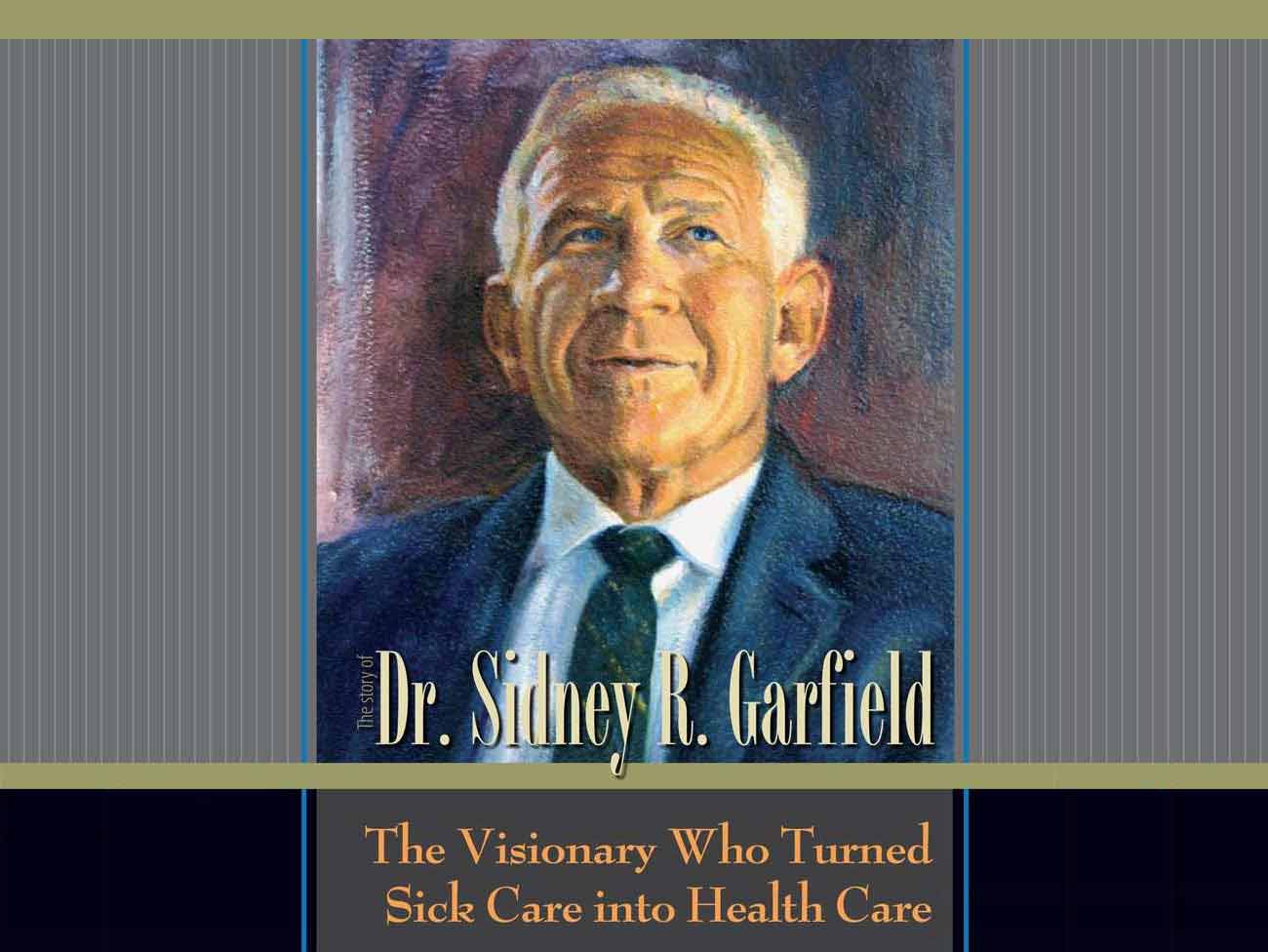

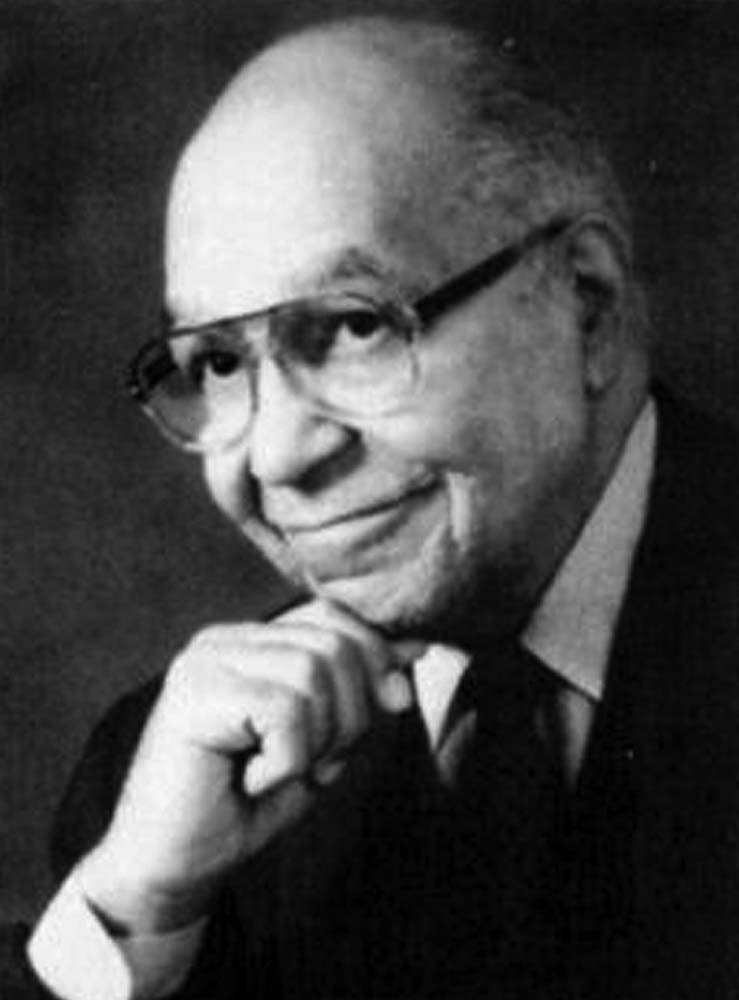

The end of the war and the return to peacetime allowed Henry J. Kaiser and Dr. Sidney R. Garfield to introduce a revolutionary model of care to Americans.

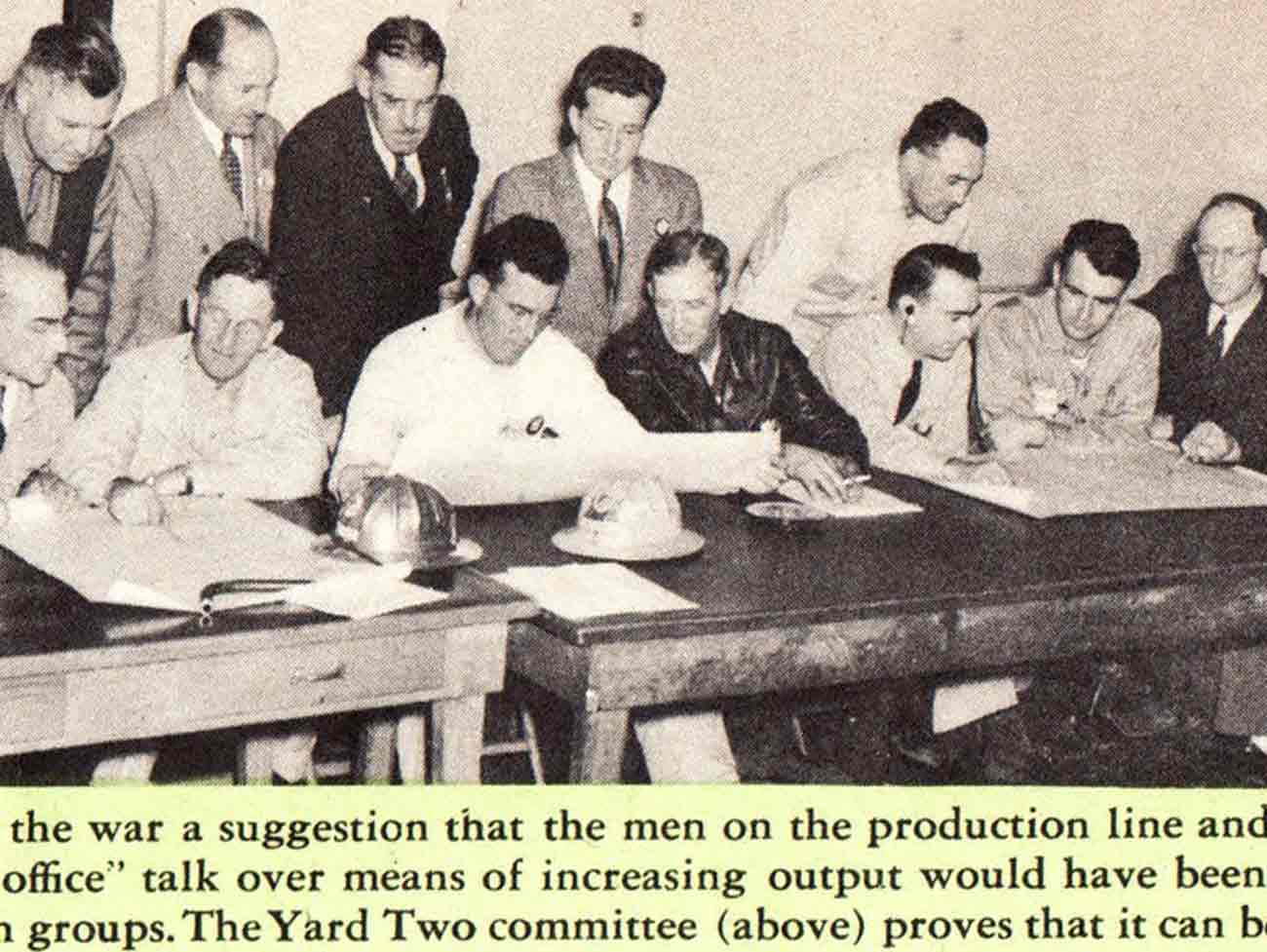

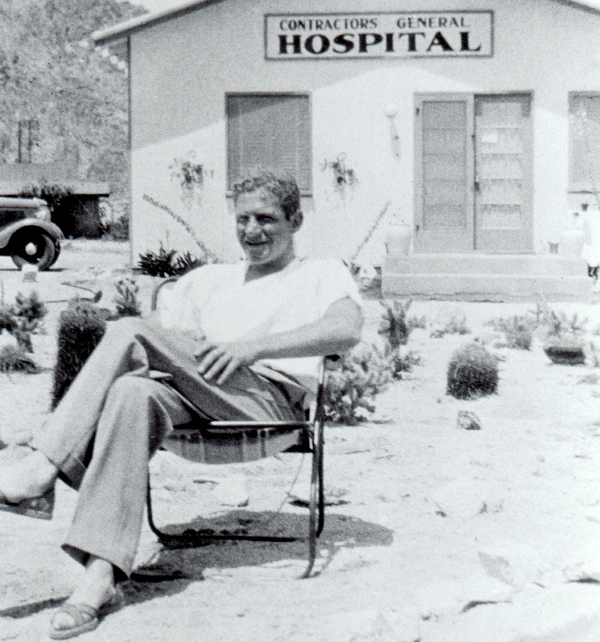

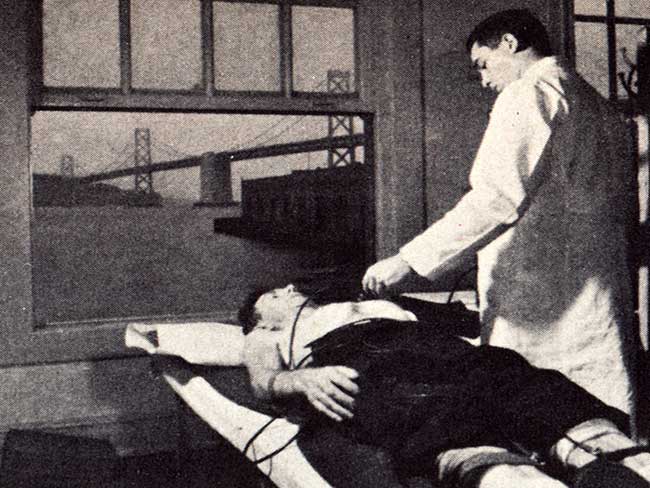

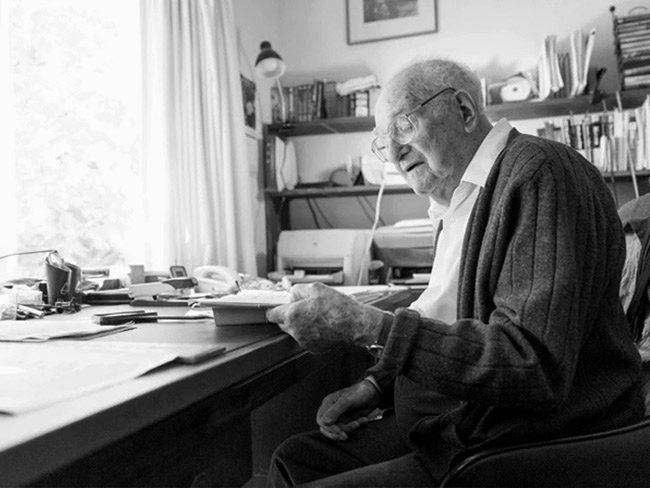

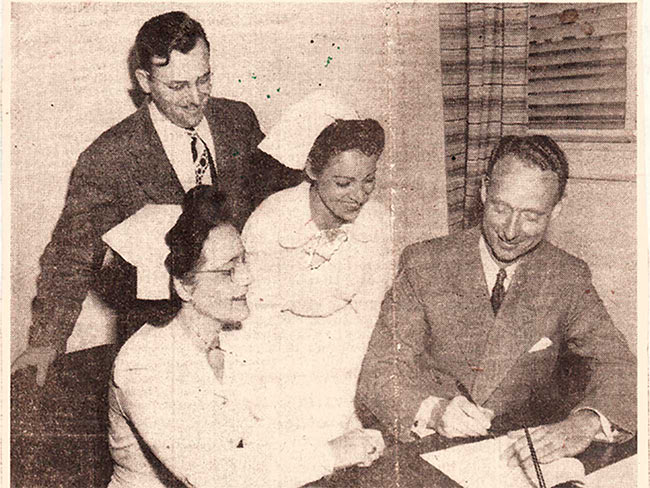

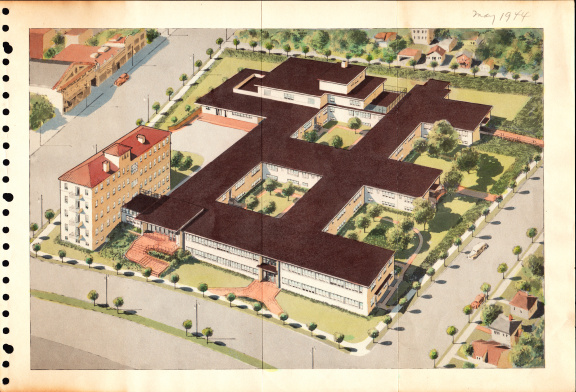

Kaiser Permanente's Oakland Medical Center started with rebuilding of the burned out shell of a former hospital, seen here in 1942 with Dr. Sidney R. Garfield, at right, and Ned Dobbs, liaison between physicians and the architects.

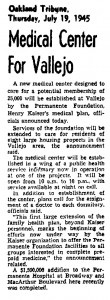

In July 1945, the curtain was about to fall on the dreadful years of World War II, and Dr. Sidney R. Garfield and industrialist Henry J. Kaiser were raising the curtain on their plans to expand their prepaid Permanente Foundation Health Plan — later renamed Kaiser Foundation — beyond Kaiser’s employees to the general public.

They announced that the “first large extension of the family health plan” beyond Kaiser workers would be in Vallejo, California, about 30 miles northeast of San Francisco.

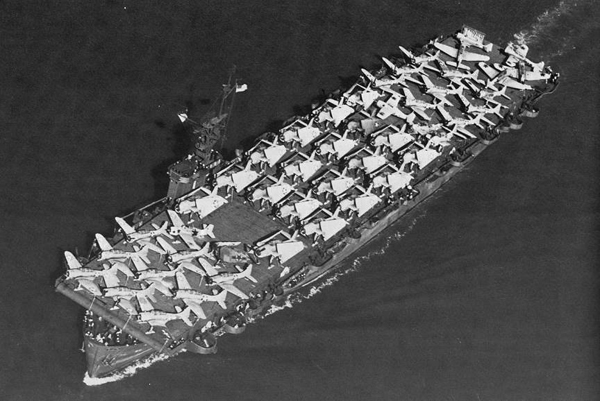

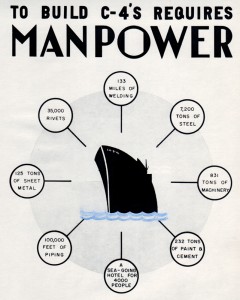

The idea of going to Vallejo with a Kaiser Foundation Health Plan and Hospital resulted from a grassroots invitation from citizens there—a sort of populist request for prepaid medical care. That should come as no surprise. The new medical care program — nicknamed “a Mayo Clinic for the common man” by one writer of the era — had been a hit with workers in the wartime Kaiser Shipyards in nearby Richmond and was getting nationwide media notice.

“I don’t see why this can’t be done everywhere, for everyone,” said one shipyard worker. “This should be for everybody,” added another. “We must organize and demand this not only for us workers but for all their families. It should be for everybody in America.”

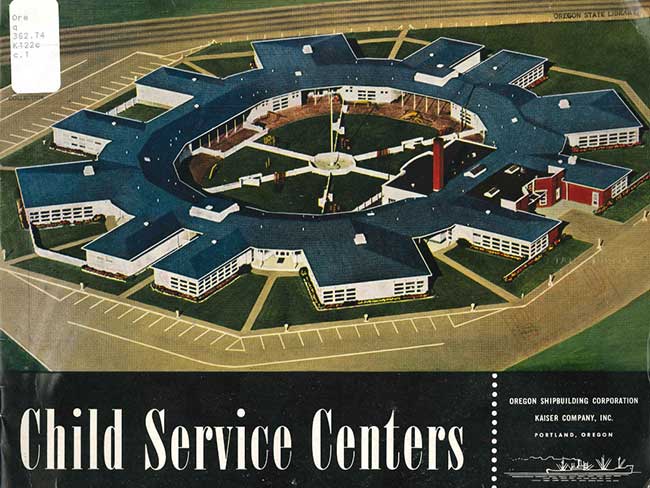

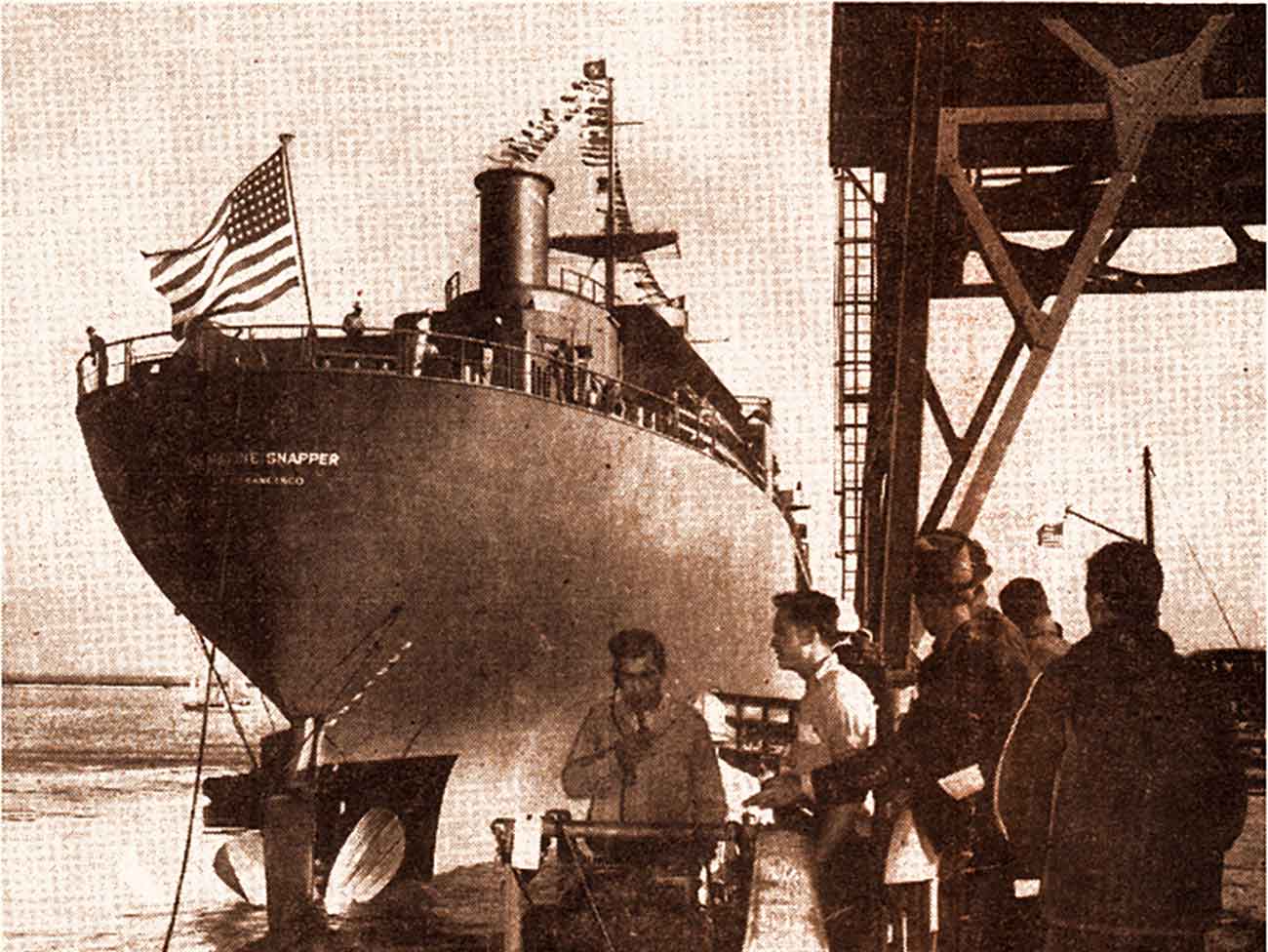

Against that backdrop, Kaiser Permanente was invited to town by a tenants’ council of the Vallejo Housing Authority to provide care for residents of 8 large wartime public housing dormitories. A doctor was assigned to each dormitory and a clinic was set up within an existing public health service infirmary.

Meanwhile, with the cooperation of local physicians, a citizen's committee had unraveled wartime bureaucracies to get the government-sponsored Vallejo Community Hospital opened in 1944. It was needed because the Mare Island Naval Shipyard at Vallejo and the nearby Benicia Arsenal ordnance facility had drawn thousands of wartime civilian workers. The city's few doctors had been swamped by a flood of new patients.

However, with the war ending, the government was no longer willing to support a community hospital. The military-style facility — long, low buildings spread over 30 acres — closed after the war ended in August, leaving thousands of civilian families without medical care.

Before long, the not-for-profit Kaiser Foundation Health Plan needed a full-service hospital in Vallejo. So, on April 1, 1947, Kaiser Permanente re-opened the 250-bed Vallejo Community Hospital as its own, having first leased it as surplus property from the Federal Works Agency. Later, it bought the hospital at the site where Kaiser Permanente’s Vallejo Medical Center remains to this day.

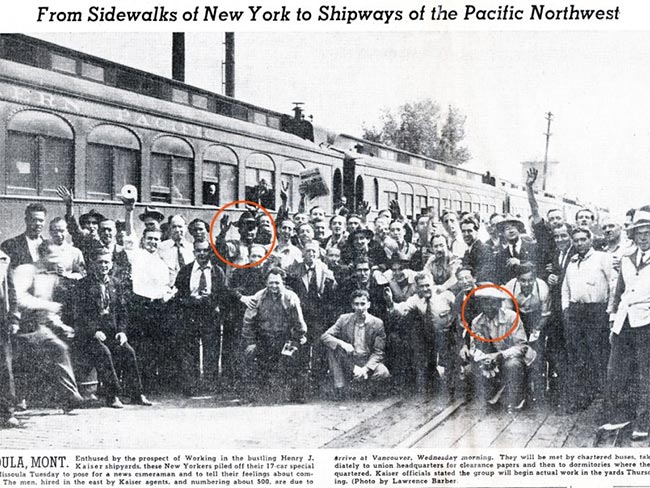

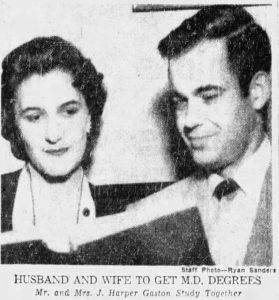

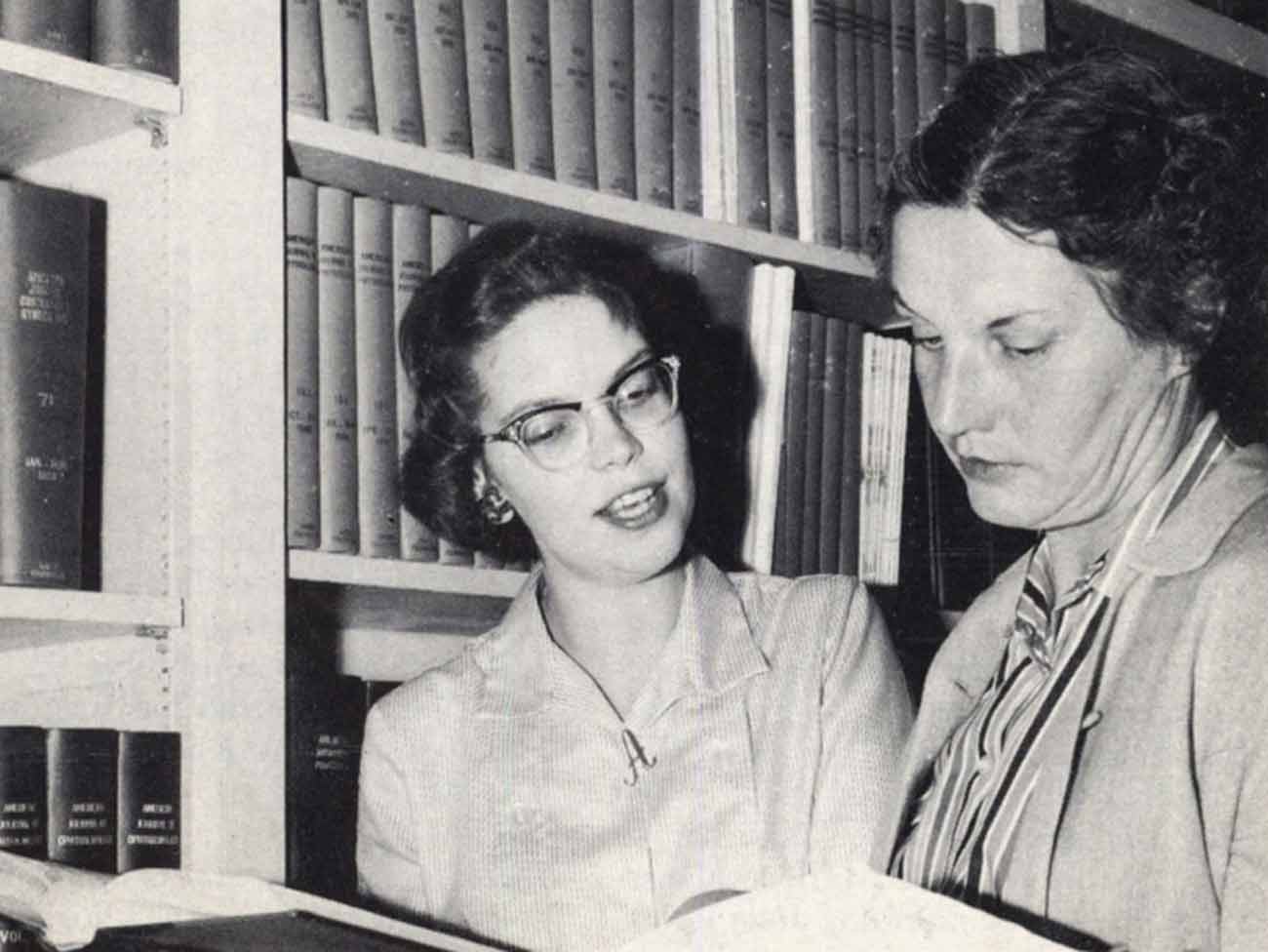

This Oakland Tribune clipping is one of many news stories when Kaiser Permanente began opening its doors to the public.

“This … marks the beginning of efforts now underway by the Kaiser organization to offer Permanente Foundation facilities to all groups interested in complete prepaid medicine,” the July 1945 announcement read. The existing facilities were those on the Home Front of World War II serving Henry Kaiser’s shipyards and steel mill. They were in Richmond, Oakland, and Fontana in California and in Vancouver in Washington state.

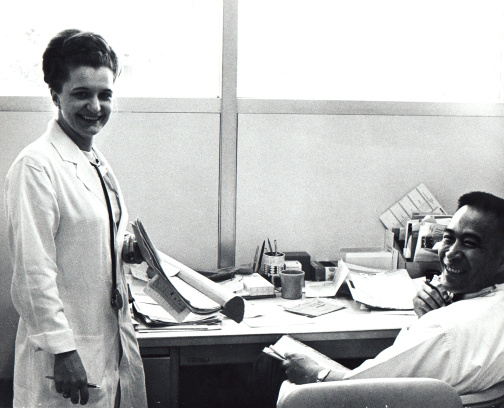

A few days later, Clyde F. Diddle, administrator of the Oakland Medical Center, told the San Francisco Chronicle that the Oakland hospital was being opened to the public under four principles: prepayment, group medical practice, adequate facilities, and “a new medical economy.”

“This ‘new economy,’ strongly opposed in part by some factions favoring the traditional family physician-patient relationship, follows the old Chinese practice of paying the physician while you are well,” the Chronicle said.

Added Diddle, “We offer medical service from nasal spray to surgery—and all under one roof. The important thing is that there are no barriers to early treatment. …Patients are encouraged to come in early…”

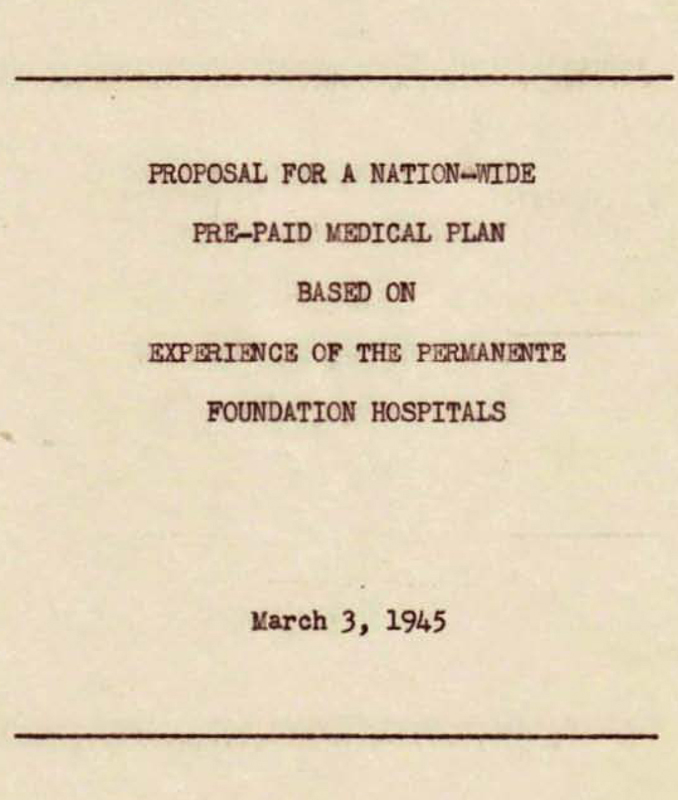

The Chronicle article also reported that Henry Kaiser was preparing a proposal for Congress to establish a nationwide system of voluntary prepaid medical care. This would be the first of many continuing efforts to support Sidney Garfield’s dream of health care for all Americans that have continued to the present day.

These historic events are honored today by the Rosie the Riveter/World War II Home Front National Historical Park in Richmond, which includes historic sites of the wartime medical care program. Notes National Park Service interpretative materials: “Today, prepaid medical care is central to American culture — it is a legacy of the WWII Home Front.”

Forecasts in 1945 projected eventually serving about 25,000 people in Vallejo. Today, the Vallejo Medical Centers serves about 10 times that number in California’s Napa and Solano counties alone. The entire Kaiser Permanente multi-state program serves 8.6 million members.

The “official” date for Kaiser Permanente’s opening to the public became October 1, 1945, but the work got underway in earnest starting in July.