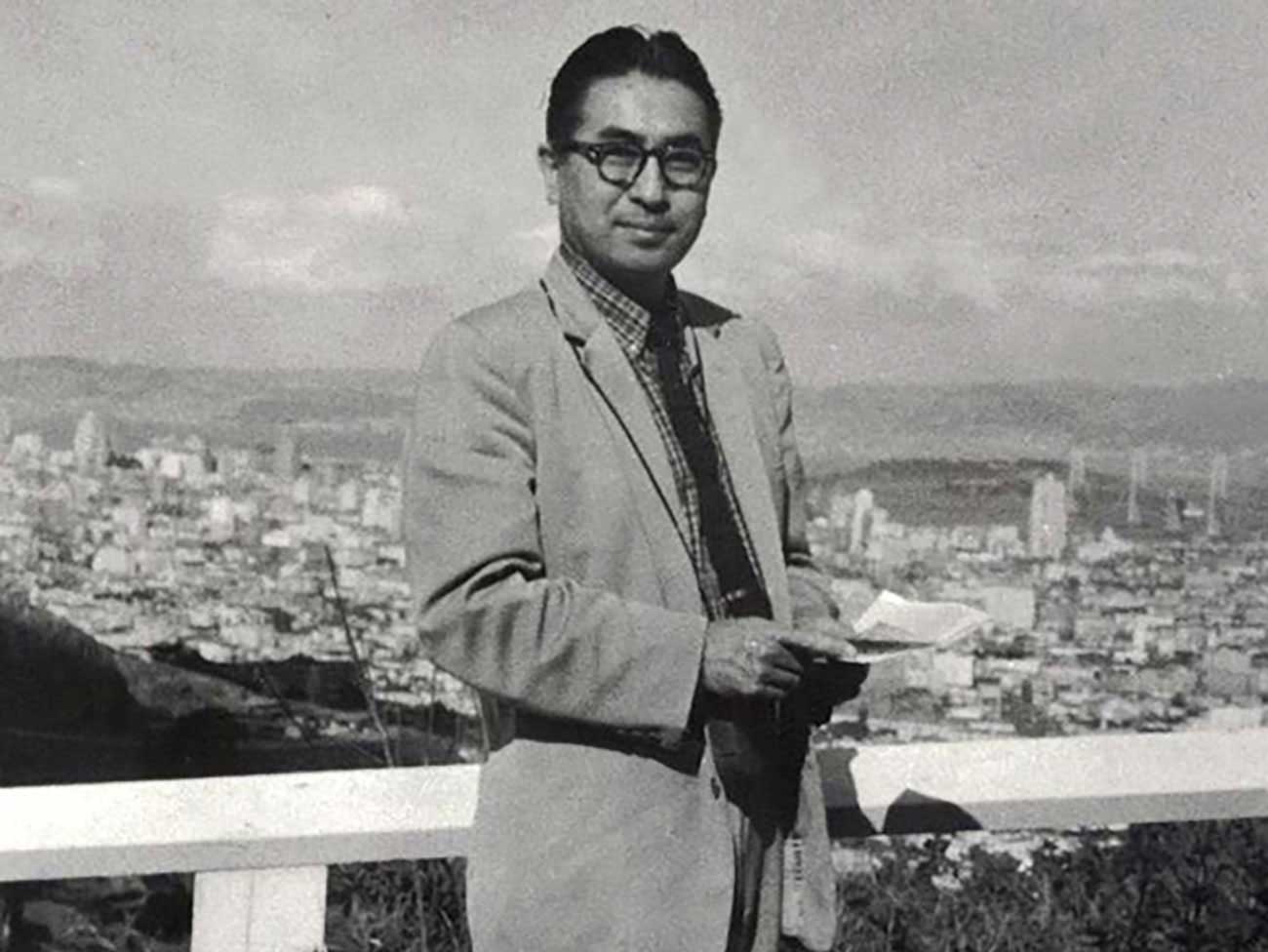

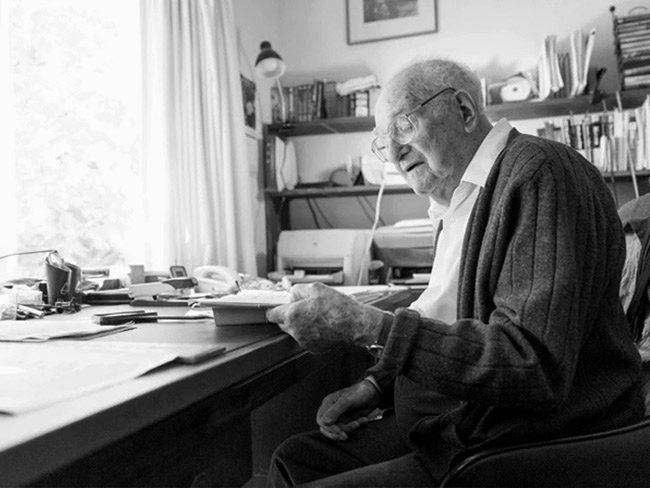

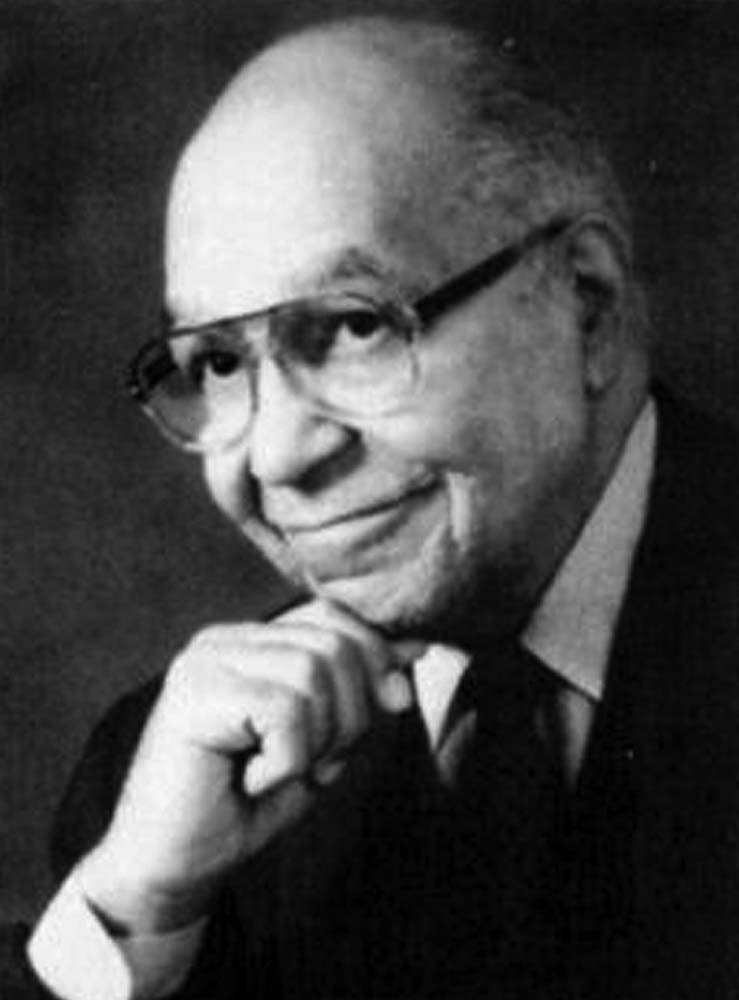

Dr. Charles M. Grossman, 1914–2013 — founding Northwest Permanente physician

In memoriam: Remembering and reflecting on a pioneering physician from Kaiser Permanente Northwest.

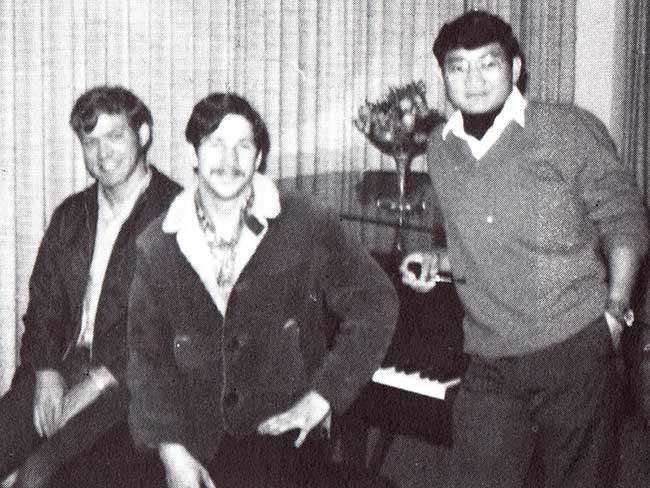

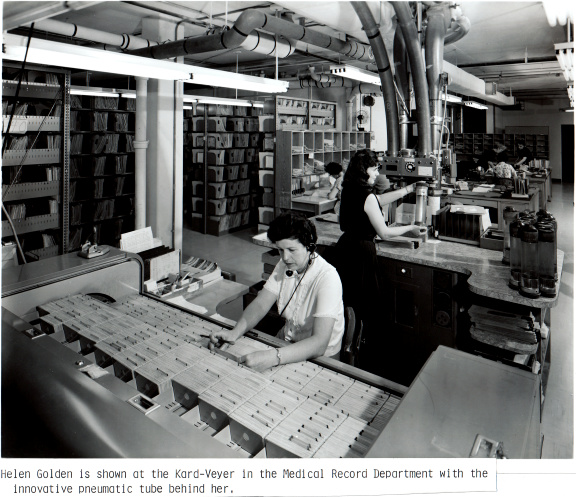

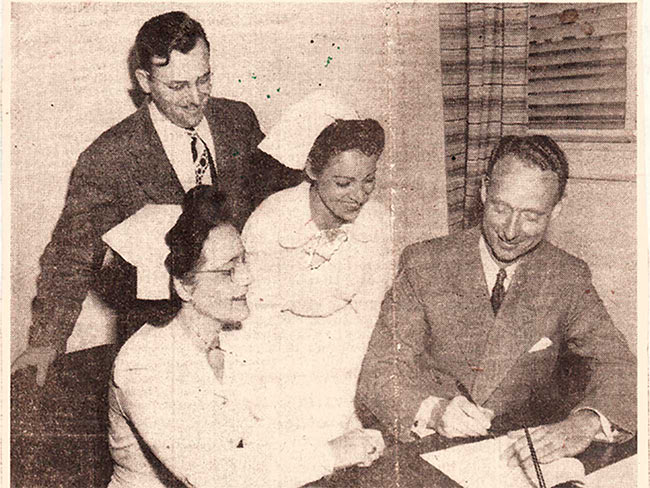

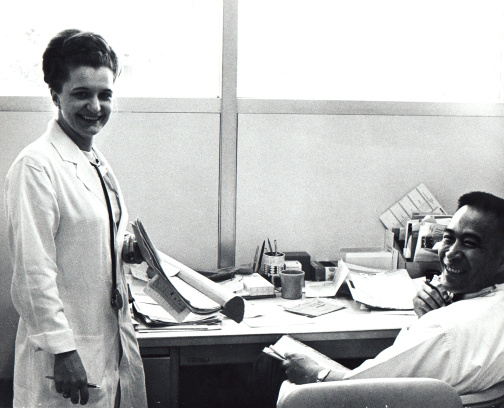

Founding Northern Permanente physicians with spouses at the El Rancho Roadhouse, Portland, Oregon, 1949. Left to right: Frosty and Charles Grossman, Virginia and Barney Malbin, and Nadja and Morris ("Mo") Malbin. Photo courtesy Charles Grossman, published in The Portland Red Guide by Michael Munk.

Dr. Charles Grossman, one of the 12 original partners of what was originally called the Northern Permanente Group (Oregon and Washington), passed away July 16, 2013, at age 98.

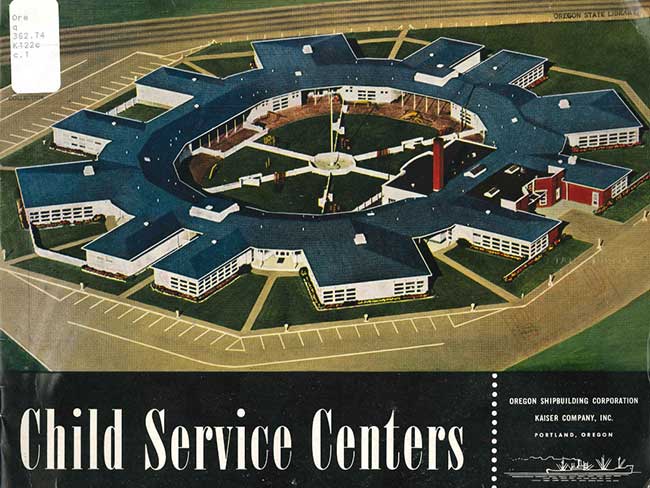

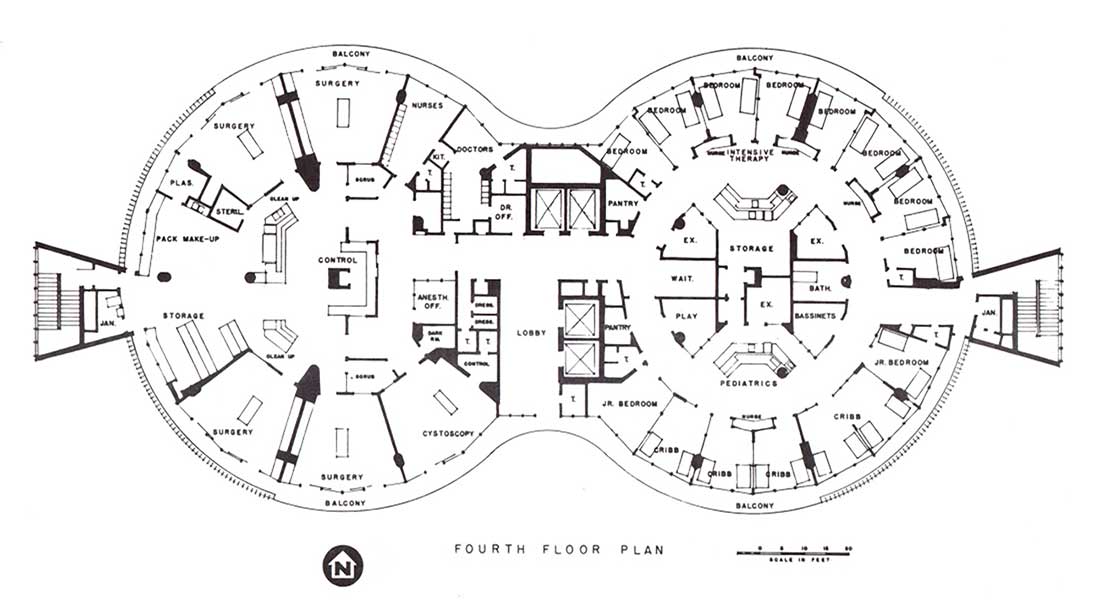

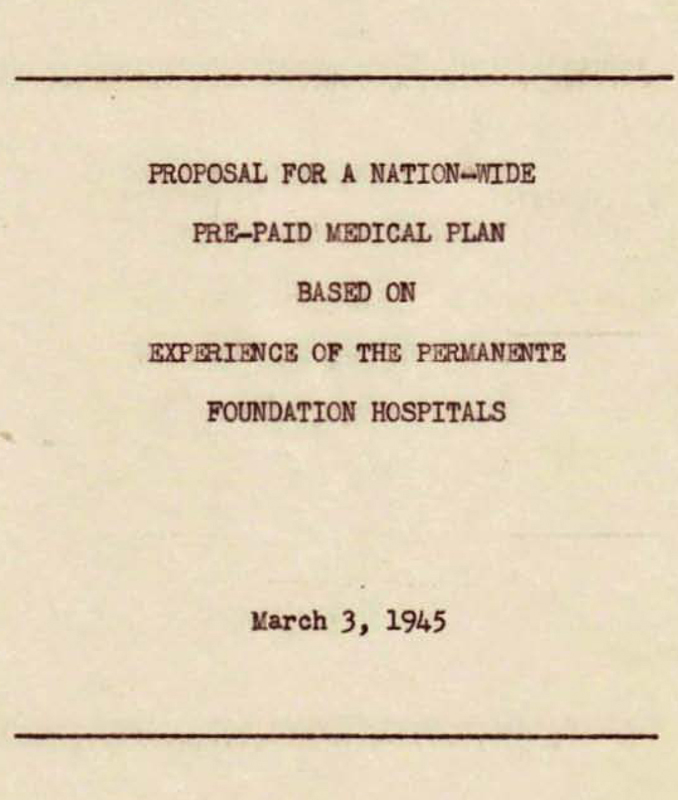

Dr. Grossman came to Vancouver, Wash., in October 1944 to join the 45 physicians of the Northern Permanente Foundation hospital. It was here that the wartime health plan covering 60,000 Kaiser shipyard workers in Oregon and Washington was in full swing. This was the formative crucible of what would later become the public Permanente Health Plan. Grossman, having just completed his medical residency at Yale, at which he took part in the first U.S. clinical trial with penicillin, joined the pioneering medical group “…induced he said, by the annual salary of $8,400 — considerably more than Yale had offered.” 1

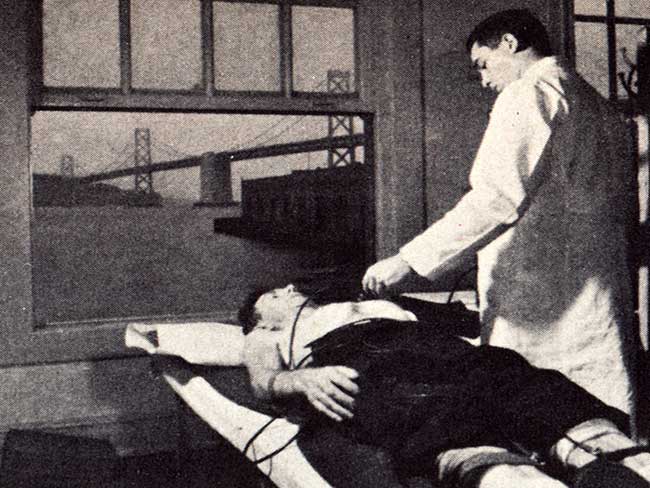

Northwest physician and historian Dr. Ian MacMillan recounts a story of those early years: Dr. George Bookatz, a talented surgeon with a flair for humor, once admitted “a male with chest abscess” for a drainage procedure. The patient was Grossman’s dog, an adoptee from the local animal shelter. Its vigorous protests prompted another patient awaiting treatment to remark with alarm that the suffering patient in the adjoining cubicle had begun to bark like a dog.2 While treating the men and women in the shipyards Dr. Grossman looked into the prevalence of pneumonia, where the incidence was 18.5 per 1,000 employees, a figure much higher than among the workers’ families and almost twice that that Dr. Morris Collen was finding in the Richmond, Calif., shipyards. Dr. Grossman concluded that certain workplace conditions played a role, with painters and chippers appearing to be at the highest risk.3 But the samplings were too small and the time period too short to arrive at any definitive conclusions.

When the war ended and the shipyards closed, the Northwest group suffered the same attrition as the Oakland hospital. Dr. Grossman noted that within six weeks after V-J Day (August 14, 1945), about 35 of the 45 medical staff quit Permanente to return to private practice.4 Besides Grossman, that left Wallace Neighbor, brothers Morris and Barney Malbin, Ernest Saward, Walter Noehren, Norbert Fell, Ernest Spitzer, Katherine Van Leeuwen, pediatrician Margaret Ingram, and two only identified in a recent interview by Dr. Grossman as “Knos (Bookatz?) and Haeber.”

Grossman recalled:

"All of us were firmly committed to the prepaid group health concept and we decided to rebuild Northern Permanente rather than allowing it to close down... With all the Kaiser shipyards on the West Coast closing, we had no patients or income. In addition, we were faced with opposition from the leaders of both Oregon and Washington medical societies to “socialized medicine” as they considered Permanente to be."

In public, they argued on a less ideological level that with the war over and the shipyards closed, the emergency that persuaded them to tolerate Northern Permanente was over. Their opposition was so fierce that Permanente doctors were barred from membership in the local medical societies and we therefore had no admitting privileges at area hospitals.5

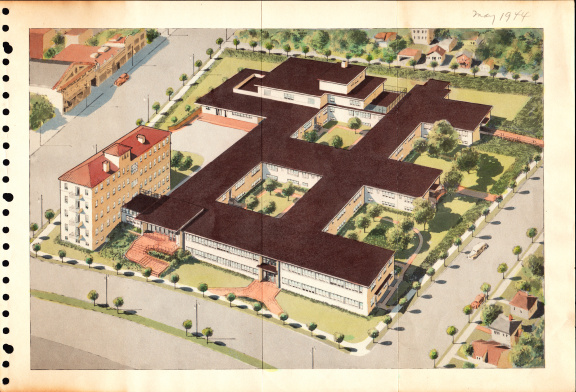

In November 1945 Dr. Grossman began a year of absence from Northern Permanente to fill an internist position in the Southern California Permanente Medical Group at the Kaiser steel mill in Fontana, Calif. He rejoined the Northwest Permanente Medical Group in October 1946. Although the practice acquired the Vanport, Ore., hospital in 1947 to expand its service area, a 1948 flood wiped out both the town and the hospital. Dr. Grossman himself waded in to salvage a 50-pound EKG machine.

During the late 1940s, the Permanente plans and hospitals experienced the fractious Cold War dynamics wracking the country at that time. Dr. Grossman’s political leanings were seen by management and some other physicians as negatively affecting the medical group’s relationship with the community. A series of struggles eventually resulted in his departure in 1950.6

Dr. Grossman continued private medical practice in the Portland area, and his political activism continued throughout his life. In 1990 he was arrested during a peaceful demonstration organized by Physicians for Social Responsibility, challenging the presence of a battleship capable of carrying nuclear arms berthed near the Portland Rose Festival. His court testimony describes the scene: “I was standing silently with several other doctors and a few others with a sign in my hand saying ‘Rose Festival is a fun time, we don’t need nuclear weapons.’ About 2:30 p.m. three or four policemen approached and asked us to leave. I asked why and was told that we have no right to stand in a city park carrying a sign. . . I put my sign down and said ‘O.K. I am not carrying a sign.’ His response was that if I did not leave within 30 seconds I would be forcibly removed. I said we were creating no disturbance and again asked why such a confrontation was necessary. While I was writing [down his badge and name] my two arms were forcibly seized, forced behind my back, and handcuffs were applied.”

Dr. Grossman was one of the brave and committed physicians who stood by the Permanente practice during its most desperate times. He will be missed.

1 Permanente in the Northwest, by Dr. Ian C. MacMillan, 2010, published by The Permanente Press.

2 Ibid.

3 Grossman’s shipyard medical articles include: “Pneumococcal Pneumonia, A Review of 440 Cases,” Permanente Foundation Medical Bulletin, October 1945; “Pneumococcal Pericarditis Treated with Intrapericardial Penicillin,” New England Journal of Medicine, December 6, 1945; “Homologous Serum Jaundice Following the Administration of Commercial Pooled Plasma: A Report of Eight Cases including One Fatality,” (Grossman and Saward), New England Journal of Medicine, February 7, 1946;“Lobar Pneumonia in the Shipbuilding Industry: A Review of Five Hundred and Forty-four Cases over a One-year Period,” The Journal of Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology, September 1946.

4 Remarkably, no firm documentation exists of the names or even the number of physicians in Northern Permanente just after the war. In Medical Director Dr. Ernest Saward’s oral history, he recollects “it was either five or six, I’m not absolutely certain of that.” Ernest W. Saward, M.D., “History of the Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program,” an oral history conducted in 1985 by Sally Smith Hughes, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1986.

5 “Present at the Creation: The Birth of Northwest Kaiser Permanente,” unpublished interview edited by Portland historian Michael Munk, 2013. Physician names were corrected by Dr. Ian C. MacMillan.

6 The details of this struggle are presented in both Michael Munk’s interview with Grossman and in Permanente in the Northwest, by Dr. Ian C. MacMillan, 2010.