Kaiser’s postwar suburbs designed for pedestrian safety and fitness

Model neighborhoods close to jobs and laid out with meandering lanes and few busy cross streets.

Here’s a photo of a typical Kaiser Community Home in Southern California. Photo courtesy of the Bancroft Library.

Henry J. Kaiser and home builder Fritz Burns had a brilliant idea in the mid-1940s for encouraging people to use their feet for transportation. Kaiser and Burns were known at the time for their “model suburbs,” new neighborhoods that were laid out with winding lanes, rolling curbs, a minimum of busy intersections and space for schools, churches and stores.

Neither speed bumps nor other traffic-calming schemes were necessary on meandering streets where children rode their one-speed bikes and played football and kick-the-can without fear of a fast car running them over.

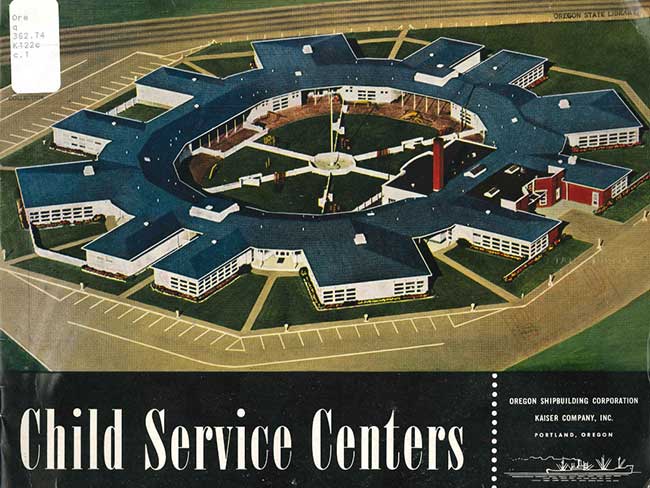

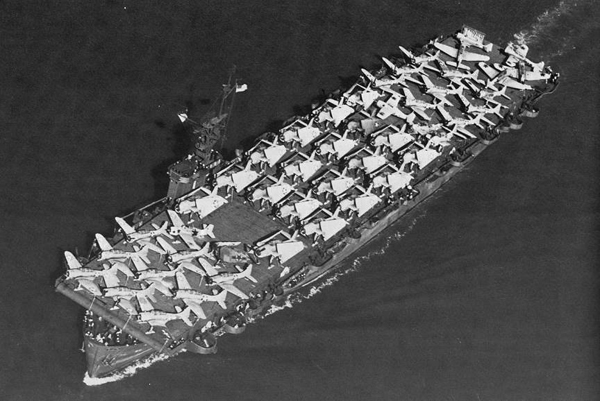

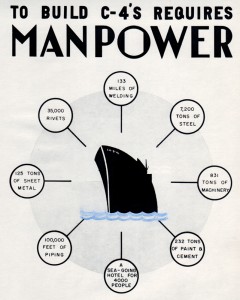

To meet a severe housing shortage at the end of World War II, Henry Kaiser, who had pioneered streamlined production methods to turn out cargo ships in record time, saw another opportunity to innovate and mass produce. Home construction had slowed way down during the war, and the population was beginning to soar.

Housing boom fed by GI Bill and FHA

Returning servicemen and women were settling and contributing to the baby boom, and financing provided by the GI Bill and the Federal Housing Administration fueled the surge in demand for new, affordable houses.

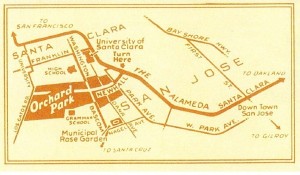

This photo in a Kaiser Community Homes brochure shows a sign urging slow driving to protect children in the Orchard Park subdivision in San Jose.

Kaiser hooked up with Burns and launched Kaiser Community Homes. The company embraced the Federal Housing Administration standards to develop thousands of low-priced homes for the common man. They built minimal tract residences of about 1,000 square feet on the periphery of urban areas in close proximity to industries that employed many workers.

Burns and his Northern California counterpart David Bohannan argued for streamlined transit:

“Transportation to business areas should be rapid and direct, and when possible, jobs should be within walking distance,” Burns and Bohannan wrote in “Postwar Housing,” a state of California booklet published in 1945.

Panorama City, Kaiser Community Homes’ largest development, incorporated these principles, and Los Angeles regional planning professionals touted the development of the Panorama Dairy Ranch in the city’s “Accomplishments 1945.”

Kaiser-Burns plan Panorama City in San Fernando Valley

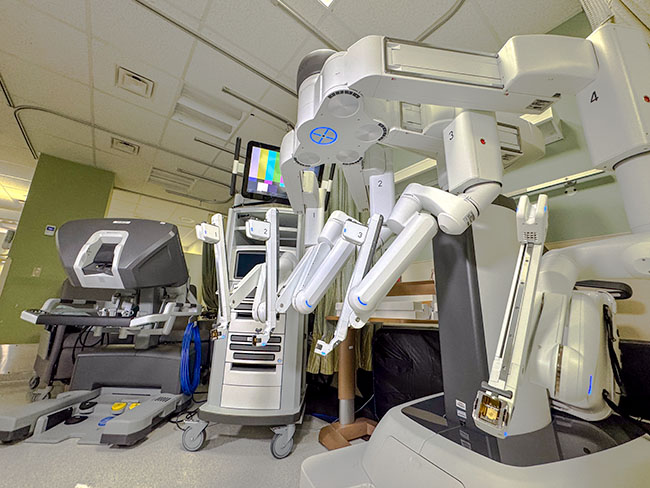

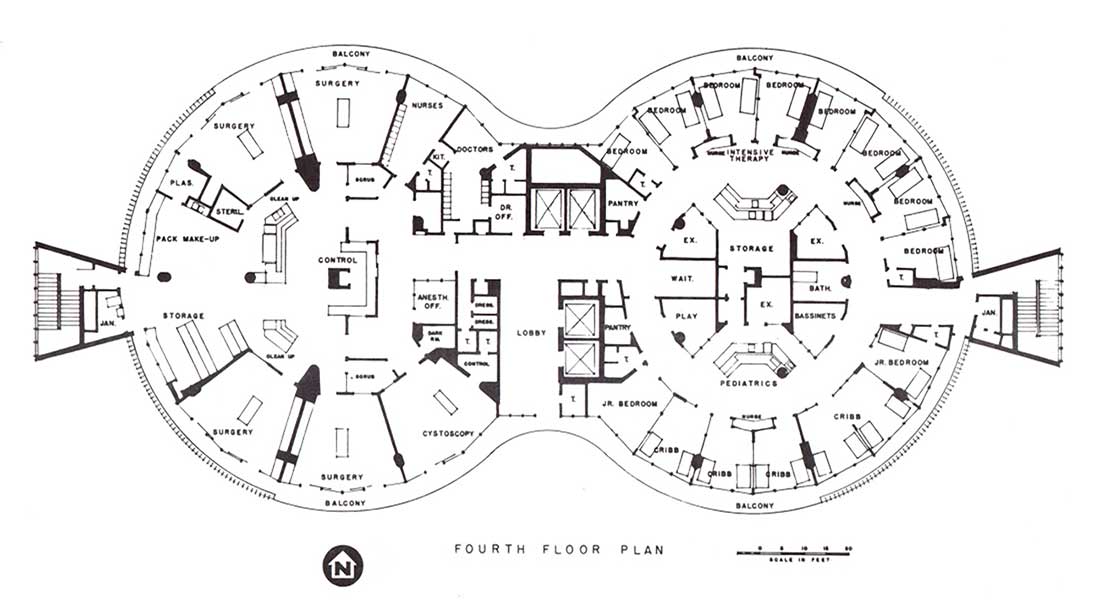

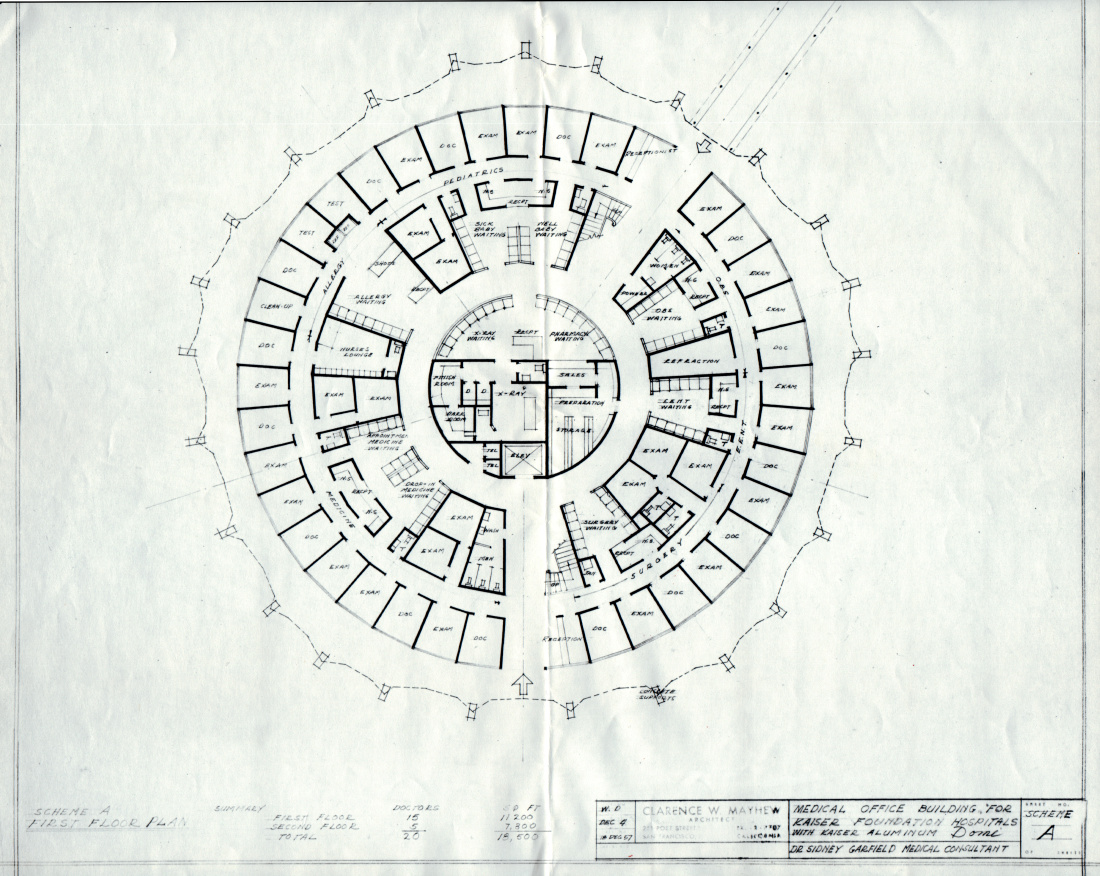

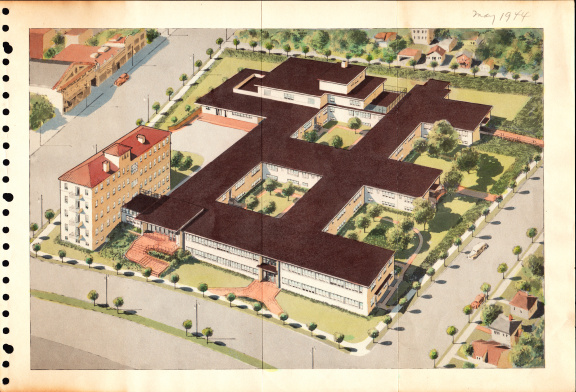

With 3,000 homes built between 1947 and 1952, Panorama City was the first large postwar community in the San Fernando Valley. In making up the blueprint for the community, Kaiser engineers also designated space for a Kaiser Permanente clinic and hospital, which was completed in 1962.

A General Motors plant completed in 1947 was situated one-quarter mile south of Roscoe Boulevard, the southern boundary of Panorama City. A Schlitz Brewery sat immediately to the east, and Lockheed and Vega Aircraft, and Precision Tool, were all within seven miles of the Kaiser development.

Kaiser and Burns sought land that was adjacent to manufacturing to fulfill their aim of building “a city where a city belongs,” wrote Greg Hise in his book titled “Magnetic Los Angeles,” published in 1997 by Johns Hopkins University Press.

Their intent was to create a regional city just outside of Los Angeles that would be self-contained and buffered from urban life. Farmlands, still flourishing with dairy cows and chickens, were to provide a buffer for the happily hemmed-in microcosm.

General Motors plant to catch up with demand

The new Van Nuys GM plant near Panorama City (closed in 1992) initially employed 1,500 workers to turn out 100,000 new Chevrolet models to catch up with Southern Californians’ demands.

Kaiser Community Homes, David Bohannon, and others also built “ideal” suburbs in the Northern California communities of San Leandro, San Lorenzo, and San Jose where Chrysler, Ford, and GM were expanding their manufacturing capacity.

Ironically, the industry that drove the creation and growth of Panorama City and other auto manufacturing areas was the eventual undoing of the pedestrian-friendly landscape. With auto ownership on the rise, transit ridership declined steadily.

“The geographical spread and low population densities of the postwar suburbs . . . made transit impractical for most people living outside the older and denser urban areas,” a 2011 California Department of Transportation report stated.

Automobile use surpasses other transit modes

By 1956, more than 54 million Americans were driving automobiles. By the end of the 1950s, 95 percent of all trips in Los Angeles were by private vehicle.

As a consequence, regional planners seemed to lose control of suburban sprawl in the 1950s and subsequent decades. Hise writes: “Regardless of how well (communities) were planned internally . . . they overwhelmed the (San Fernando) valley, as well as outer zones of other American cities.”

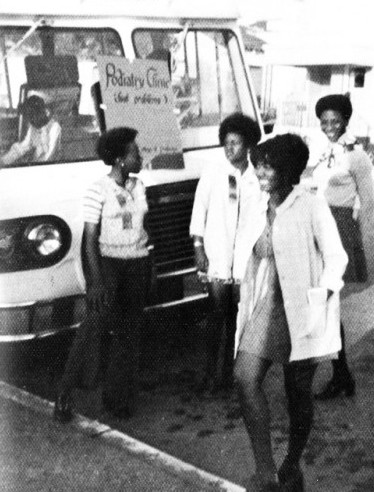

The erosion of suburban Americans’ opportunities to reach daily destinations on foot and the consequent decline in fitness has spawned such programs as Kaiser Permanente’s “Every Body Walk!” The campaign encourages people to walk whenever possible — leave the car in the garage for short trips to the market or elsewhere, take the stairs instead of the elevator, and walk for fun and fresh air every day.