Image of Rosie broadens to embrace African American women

Black women find new opportunities to elevate work status on the World War II home front.

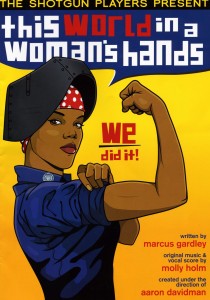

The National Park Service has adopted this updated image of "Rosie the Riveter" for a poster and T-shirt.

The colorful portrait of a strong, confident, and savvy Black woman on an updated version of what has become known as the ubiquitous Rosie the Riveter “We Can Do It” poster packs a powerful message about African American progress.

The actual image of "Rosie the Riveter" appeared on a Norman Rockwell cover of a 1943 Saturday Evening Post. This is more accurately the "We Can Do It!" image, which also featured a strong working woman, originally a poster by J. Howard Miller for Westinghouse.

Like all American women who charged into munitions and war vehicle manufacturing, Black women took advantage of the opportunity to improve their lot. Many left the cotton fields of the South and the domestic service of well-off white families everywhere to answer the call to staff the war industries.

They got jobs in every industry, every region, and at almost every level of expertise. Educated Black women took part in technical aspects of building and repairing precision instruments and performed other skilled tasks.

Of the 1 million African Americans who entered paid service for the first time during World War II, about 600,000 were women.

Gender barrier difficult to breach

It was tough for “the gentler sex” of all races to break through the gender barrier to perform heavy industrial jobs that were well-paying, albeit temporary, during World War II. For Black women, whose work status was even lower than most other women, racism made the row even rougher to hoe.

But in the end, they could proudly assert: “We did it!”

Kathryn Blood, a researcher for the Department of Labor, studied the contribution of Black women to the war effort and issued her report in April of 1945.

“Working with men and women of every other national origin, the contribution [of Black women] is one which this nation would be unwise to forget or evaluate falsely,” Blood wrote.

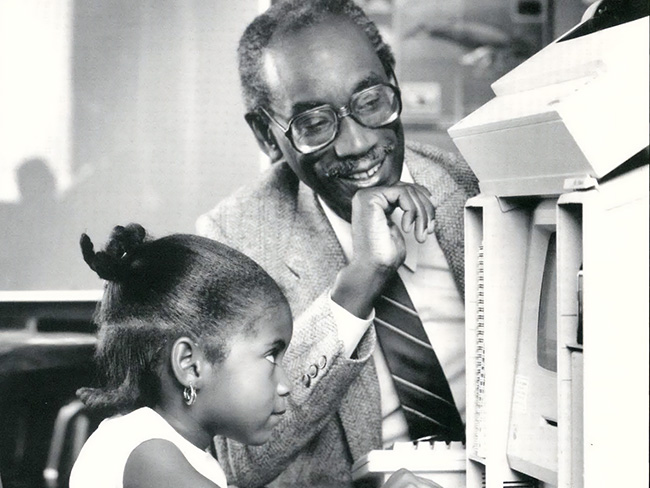

Black women made up a large proportion of the female workforce during World War II. They handled many technical and skilled jobs in America’s war industries.

Black women excel in technical roles

Black women made up a large proportion of the female workforce during World War II. They handled many technical and skilled jobs in America's war industries.

Blood described the recruiting of Black women in the Brooklyn Navy Yard in 1942: “A [Black] girl received a grade of 99, the highest rating of any of the 6,000 women who took the civil service examination for navy-yard jobs. She and another [Black] girl who also showed special aptitude for work with precision instruments were assigned to the division where binoculars, telescopes, and range finders are reconditioned.”

Blood called out the Black women who were assigned to the technical laboratory jobs in the Army Proving Ground in Aberdeen, Md.: “The girls employed in the ballistics laboratory were college graduates, and all had a background of high mathematics ... The [Black] girls in the Aberdeen laboratories ‘proved very satisfactory.’ ”

A foreman in an electrical repair department of a large eastern airline field told Blood, “One of the best men in my shop” is a [Black] girl.”

1942 Rosie poster gets a facelift

Rich Black designed this poster as a promotion for a 2009 play presented by the Shotgun Players of Berkeley, Calif.

Updating of the Rosie the Riveter poster, originally designed by J. Howard Miller in 1942, is the work of Richard Black, artist for the Shotgun Players of Berkeley, Calif., who in 2009 presented a play about Black women who worked in Henry J. Kaiser’s Richmond (California) shipyards during World War II.

Besides changing Rosie into an African American, Black also gave her a welder’s shield over her bandanna, like those worn by many female workers at the Richmond shipyards.

Black revised the poster to use as promotion for the work titled “This World in a Woman’s Hands.” The play was written by Marcus Gardley, whose grandmother was a “Rosie” in Richmond.

Gardley, a native of Oakland, Calif., is a graduate of the Yale Drama School and has taught playwriting and African American studies at Amherst University in Massachusetts. He is a visiting lecturer in playwriting at Brown University.

T-shirt honors Black Rosies

In 2009, the Shotgun Players gave special performances at the Nevin Community Center in Richmond as a gift to the children of the Iron Triangle, a section designated by the city as “disadvantaged.” Many children of the Iron Triangle are descendants of the original Black Rosies.

Recently, the Rosie the Riveter/World War II Home Front National Historical Park made the updated poster into a T-shirt that is sold online and in the park’s Visitor Education Center gift shop in Richmond. “They are just flying out the door,” says park ranger Betty Reid Soskin, who worked in a Jim Crow union office at the shipyards during the war and consulted with Gardley in his research for the play.