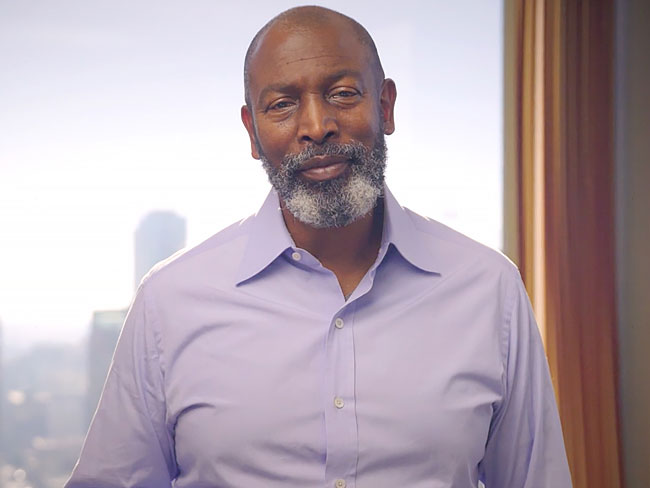

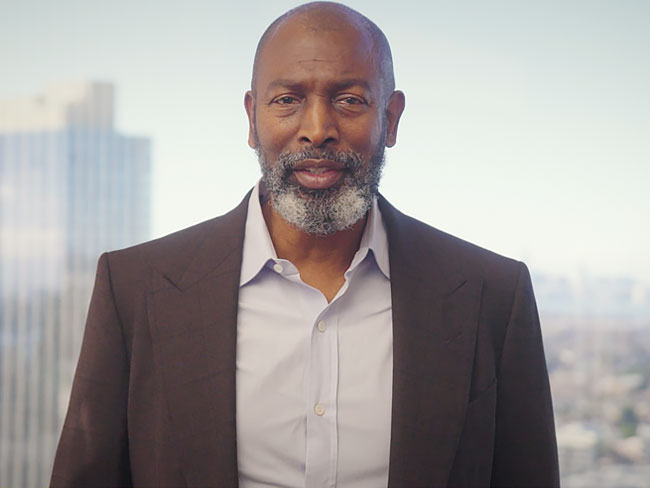

Kaiser's first labor attorney in the thick of union battles

Harry F. Morton was an instrumental figure at Henry J. Kaiser's side, setting the foundations of early labor beliefs and practices.

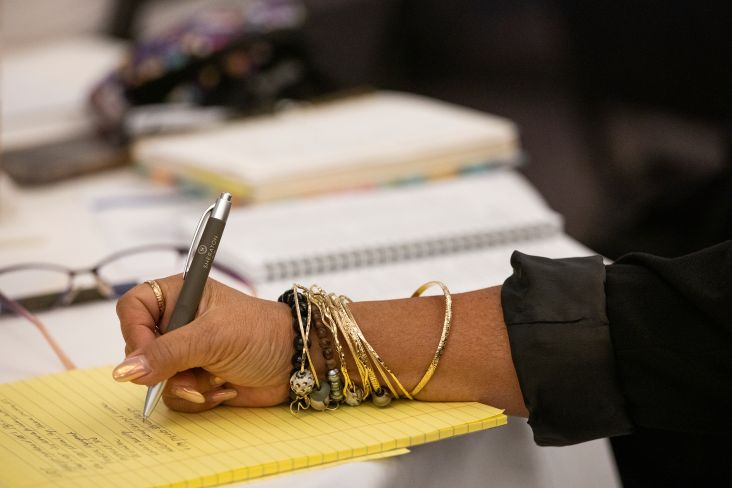

Carl Brown (left), president of the Independent Foremen's Association of America, confers with Harry F. Morton while representing Kaiser-Frazer. UPI newspaper photo, 2/19/1949.

In 1941, before the United States entered World War II, Henry J. Kaiser was already building cargo ships for the British war effort. Early on, labor jurisdiction issues loomed large, and Kaiser’s labor man Harry F. Morton had his hands full.

Before the shipyards opened, Kaiser representatives signed a closed-shop agreement with American Federation of Labor-affiliated unions and hired a handful of workers; when the yards began full operation, the thousands of new workers were required to join the AFL.

Because many of them were already members of Congress of Industrial Organizations-affiliated unions, they were subsequently discharged. The CIO filed a petition with the National Labor Relations Board.

Aerial photo, Todd-California Shipyard in Richmond, CA (later Permanente Metals shipyard #1), circa 1941

The “industry” side proposed a formal proportional allocation among the unions for journeyman jobs for welders, but this did not sit well with the nine AFL unions whose members included welders.

Eventually, a compromise was reached in which welders in the shipyards would not be required to maintain membership in more than one union and that employment would not require the purchase of a permit fee.1

Morton aligns with the AFL in closed shop fight

When the jurisdiction wars erupted again in 1943, Morton fought alongside the shipyard craft unions and received a landmark favorable ruling.

The U.S. government had charged that the Kaiser shipyards in Portland had acted unfairly in favoring the American Federation of Labor over the emerging, competitive, and radical CIO.

This time Congress’ help was called upon and passed what is known as the “Frey amendment” (named after the head of the AFL Metal Trades Department, John P. Frey). The CIO lost on a technicality.

This ruling was crucial because it meant Henry J. Kaiser could run a closed shop in his shipyards, and the production of ships for the war would not be jeopardized by struggles over workforce representation.

Morton read his victory telegram at a Metal Trades conference and declared: “And thus endeth another chapter in the history of the attempt of the National Labor Relations Board to break the union shop.”2

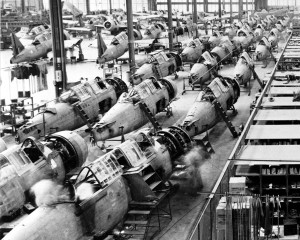

Labor man tapped for aircraft plant

In late 1943 Morton moved back East as vice president of Industrial Relations for the Brewster Aeronautical Corporation. Brewster was manufacturing F3A-1 Corsair3 fighters, but had been ineptly run.

As a favor to the Navy Secretary, Kaiser agreed to try and turn the company around. Despite cost-cutting and improved output, Kaiser was delighted to turn the plant back over to Navy officials in May 1944.

While at Brewster, Morton continued to advise Kaiser on labor. After reviewing a report by Industrial Relations Counselors4 on the then-new steel mill in Fontana, Calif., Morton sent a telegram to Kaiser executive Eugene Trefethen Jr.:

“I did not advocate a closed shop provision for the Fontana contract, but I did object to IRC’s recommendation that “. . . the company resists any demands of the union for a closed shop or union shop contract.”

“This is so foreign to all of Mr. Kaiser’s fundamental beliefs and public utterances that I could not let it go unchallenged . . . I violently disagree with the fundamental approach of IRC to labor problems.

“It is the approach of AT&T, Bethlehem, DuPont, G.E., General Motors, Standard [Oil] of New Jersey, U.S. Rubber and U.S. Steel, but not of Kaiser.

“It is my conviction that a large part of Brewster’s trouble is the result of IRC thinking and approach, and I am confident that what is needed is less IRC and more Kaiser thinking and approach in labor relations.5

Morton active after the war ends

In early 1945, Morton briefed Kaiser on a meeting he’d had with Charles MacGowan, president of the Boilermakers Union, a group that was influential (and controversial) in Kaiser’s wartime shipyards.

The subject was the merger of the American Federal of Labor with the Congress of Industrial Organizations. MacGowan opposed the merger. Morton advised Kaiser:

“I pass these suggestions on to you for what they may be worth. Personally, I don’t believe they are worth much, as [Philip] Murray and [William] Green had agreed to this once before and the agreement was later repudiated.6

Green (AF of L) and Murray (CIO) both died in 1952; it would not be until 1955 that the two labor organizations would merge under the leadership of George Meany. The AFL-CIO Murray-Green award received by Henry J. Kaiser in 1965 was named for them.

The last known records of Morton’s career reflect his negotiation with employees at the Kaiser-Frazer automobile plant. One of the provisions of the recently enacted landmark Taft-Hartley Act removed any legal obligation to bargain with foremen; Morton felt that they should keep faith with the foremen, and the Ford Motor Company managers felt they should not.

Harry F. Morton’s full story remains to be told. We lose sight of him in our research after the early 1950s. However, he now is recognized as a significant factor in shaping the climate of positive labor relations that characterizes Henry J. Kaiser’s legacy.

.

1 Harry F. Morton correspondence to Edgar F. Kaiser and Clay Bedford, December 6, 1941; BANC MSS 83/42C, ctn 9, folder 12.

2 Speech by Harry F. Morton, in Proceedings of the 35th Annual Convention of the Metal Trades Department, AFL-CIO, September 27, 1943.

3 The Brewster F3A was an F4U “Corsair” built by Brewster for the U.S Navy; Chance-Vought created and built the Corsair, which also was built under contract by Goodyear.

4 In the wake of the horrific Ludlow Massacre in the Colorado minefields of 1917, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., created a labor-management think tank that today is known as Industrial Relations Counselors, Inc.

5 Telegram from Harry F. Morton to Eugene Trefethen Jr., about IRC report on Fontana, October 1, 1943; BANC MSS 83/42C, ctn 19, folder 25.

6 Interoffice memo, Fleetwings Division of Kaiser Cargo [aviation manufacturing, Bristol, PA], from Harry F. Morton to Henry J. Kaiser in New York, January 22, 1945; BANC MSS 83/42C, ctn 151, folder 12.