Iron nurse Dorothea Daniels had a soft spot for nursing students

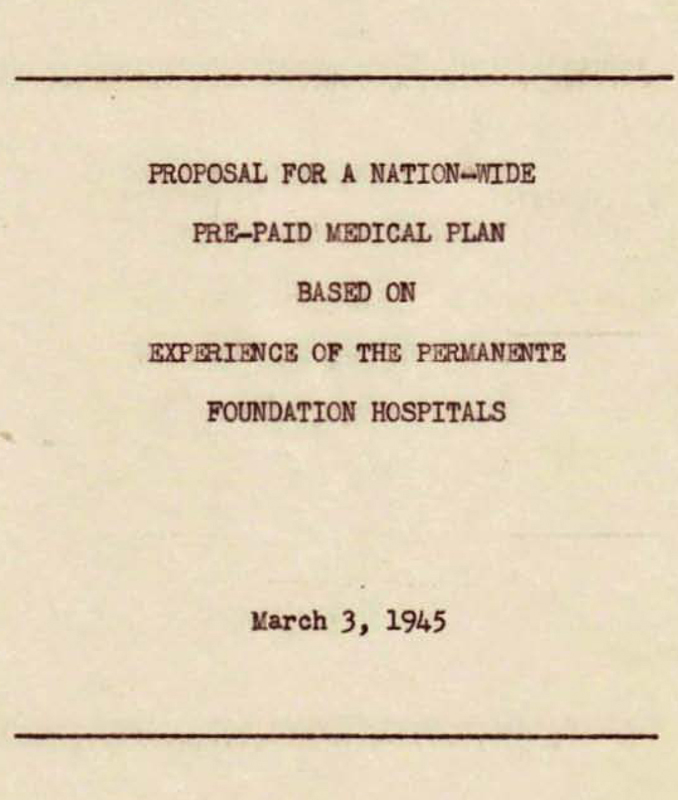

The Kaiser Foundation School of Nursing students received effective curriculum education and clinical beyond filling staff roles at hospitals.

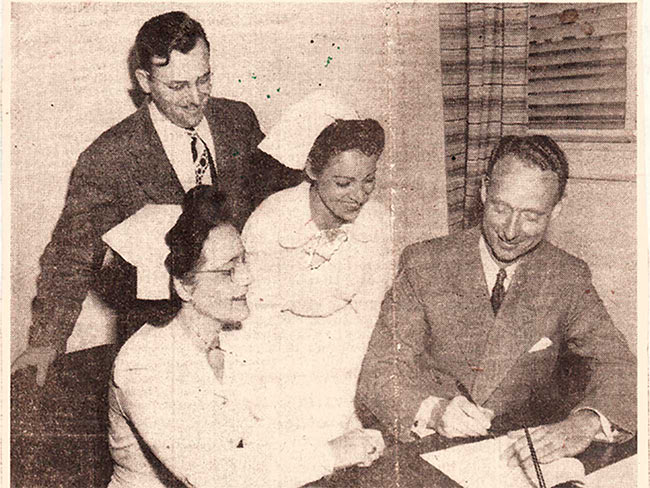

Permanente Foundation Nursing School graduation 1951. Dorothea Daniels at far left, Clair Lisker, third from right.

Daniels at right, Lisker second from right, 1950 Permanente Foundation Nursing School capping ceremony in Oakland, California. Note Daniels’ Phillips Beth Israel cap.

Read almost anything about Permanente Foundation School of Nursing’s first long-term leader Dorothea Daniels, and a caricature of a stern, tough-shelled, by-the-book, and proper nurse comes to mind. Daniels, a product of New York, rattled her students, nurses, and many physicians with her exacting demand for perfection in all things related to patient care and protocol.

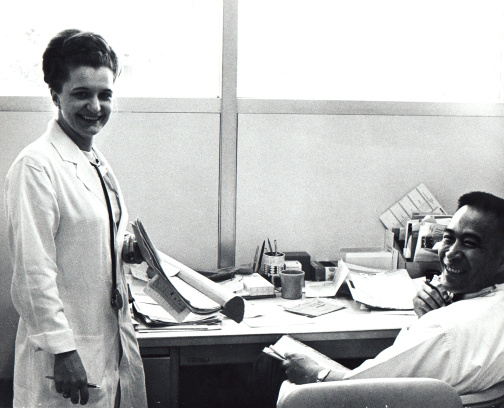

She made the nurses work and study hard in restrictive conditions and she didn’t hesitate to correct a physician who displeased her. “She came from a different cut of cloth,” wrote John Smillie, MD, in his history of the Permanente Medical Group. “She regarded herself, and I think quite properly, as a peer of any of the doctors she was dealing with.”

Migrating to California from New York City after the war ended in 1945, Daniels brought to Permanente her solid education (a doctorate in education from New York University) and experience running a nursing school in that city. From 1936 to 1945, Daniels was the director of the Phillips Beth Israel Hospital School of Nursing.

Daniels imposed strict rules for student lifestyle

Not unlike other nursing schools of the time, Phillips stressed the students’ need to conform to strict standards of behavior, dress and health habits. House mothers hovered over the students to make sure they didn’t misbehave. “Nurses were not permitted to marry while in training, and subsequent marriage was grounds for instant dismissal,” according to the school’s current website.

At Phillips, nursing students worked 6 days a week and curfews were rigorously enforced. Pupil nurses were disciplined if they stayed out all night. “Dress inspections took place in the dining room, and students were weighed once a week to make sure they did not ‘get too heavy’ since there was a professional necessity for nurses to ‘look well.’

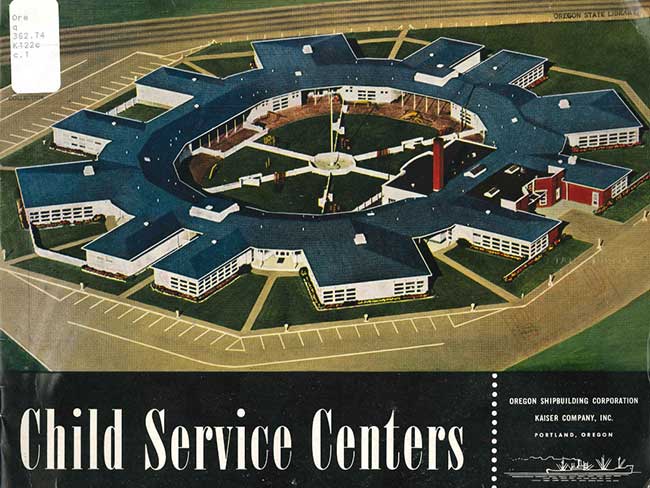

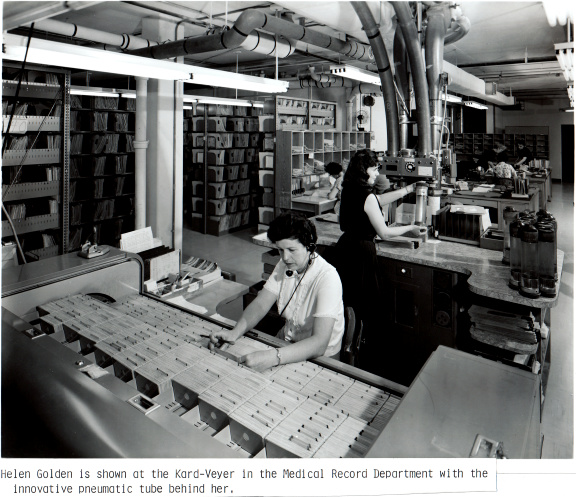

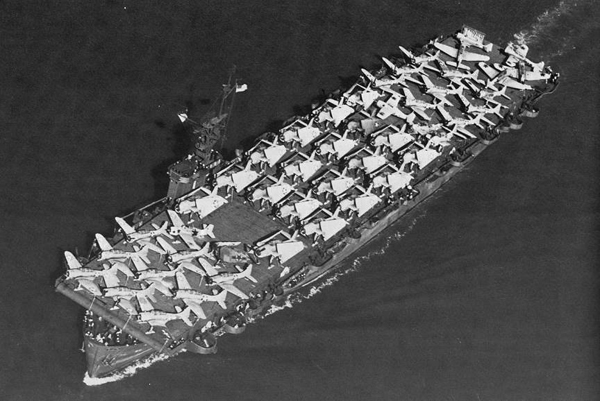

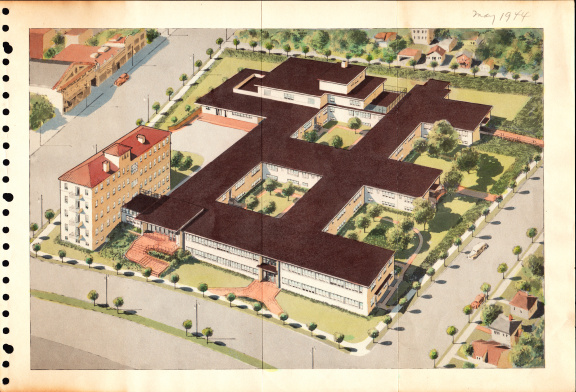

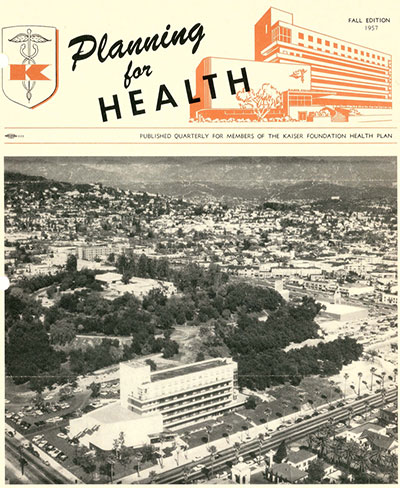

Kaiser Foundation School of Nursing in an old hotel building on Piedmont Avenue near the Oakland hospital, 1948 to 1976

“Hospital director Daniels insisted on student nurses who looked healthy and fit, believing that if students were overweight, they could not work hard and take care of patients,” the school historians reported. “There was concern (during the 1930s) that nurses did not get enough exercise and recreation.’”

Daniels gets support for her view of fitness in a textbook for orienting student nurses in the 1930s: “Curative medicine gives place to preventive medicine, so must (the nurse) be prepared to understand and apply intelligently the principles of prevention. “The nurse of the future must exemplify health, and teach it. Humanity is ready to cast off sickness.”

Encouraging nurses to spend leisure time wisely

In 1940, Daniels embarked on a study to assess Phillips students’ leisure time activities, including physical activities. “What Ninety Girls Like to Do in Their Free Time,” authored by Daniels, was published in the National League of Nursing Education publication. A softer side of Daniels emerges in her discussion of the study results.

“These young women (19 to 24 years for age) have developed abilities of discernment and judgment in their avocations as they develop in the school. While they are learning to assume increased responsibility, they seem to be learning how to spend their leisure time more wisely,” she wrote. She said many subscribed to a professional nursing journal, and “The most thorough inspection of the nurses’ quarters never reveals magazines of the ‘true story’ category.”

The survey results conclude that the younger girls are spending an average of six hours a week on exercise and the older girls 7.3 hours. “Within a short walking distance there is a tennis court, a swimming pool, a roller skating rink and bicycle-riding areas. “Little equipment is necessary. Sport dresses are the only necessary paraphernalia for hiking, bicycle riding, and roller skating…these types of exercise are easy to learn and give one a sense of well-being and feeling of grace,” Daniels wrote.

Once the anonymous surveys were compiled, Daniels returned them to the students and asked them to send them back with identification so she could: “aid in fulfilling the wishes stated on the papers. We found it possible to send some students to their first legitimate play; and some 25 were sent to concerts. Our physical education director was instructed to work out her program to include activities for which there were expressed preferences.”

Bringing her ideals to California

When Daniels came to California, Permanente Foundation hired her as director of nursing in the Oakland hospital. That position grew in 1948 to include the job of director of the nursing school established in 1948. As expected, Daniels incorporated into the school policies many of the ideas she had adopted in New York.

The first Permanente School of Nursing student handbook, developed in 1948, prescribed the dos and don’ts for students to get along well at the school. “Your ability as a nurse is reflected in the way you keep your room. Students must be in their own room at 10 p.m., and all lights will be out at 10:30 p.m. Guests may be entertained only in the living room between 8 a.m. and 10 p.m.” (Exceptions were made if a mother came to visit.)

“Pre-clinical students will be in the residence at 8 p.m. each day, Monday through Thursday, unless otherwise specified by the director of nurses…Your window shades will be kept drawn at night when the lights are on…Every student is expected to be adequately clothed when going through the halls. Students are expected to be tidy and well-groomed at all times. The conduct of the student nurse on and off duty must be such as will not reflect discredit on herself, her chosen profession, nor her school.”

In a 1961 nursing school report, a revised philosophy of the school was detailed. Revisiting the fitness theme, one stated role of a successful nurse was: “A teacher of healthful living.” A decade later, the Kaiser Foundation Nursing School brochure stated under personal qualifications required for admission: “General appearance is one of the considerations in the selection of students. Applicants must weigh within normal limits of the range established for height and structure.”

Daniels helped students pursue bachelor’s degree

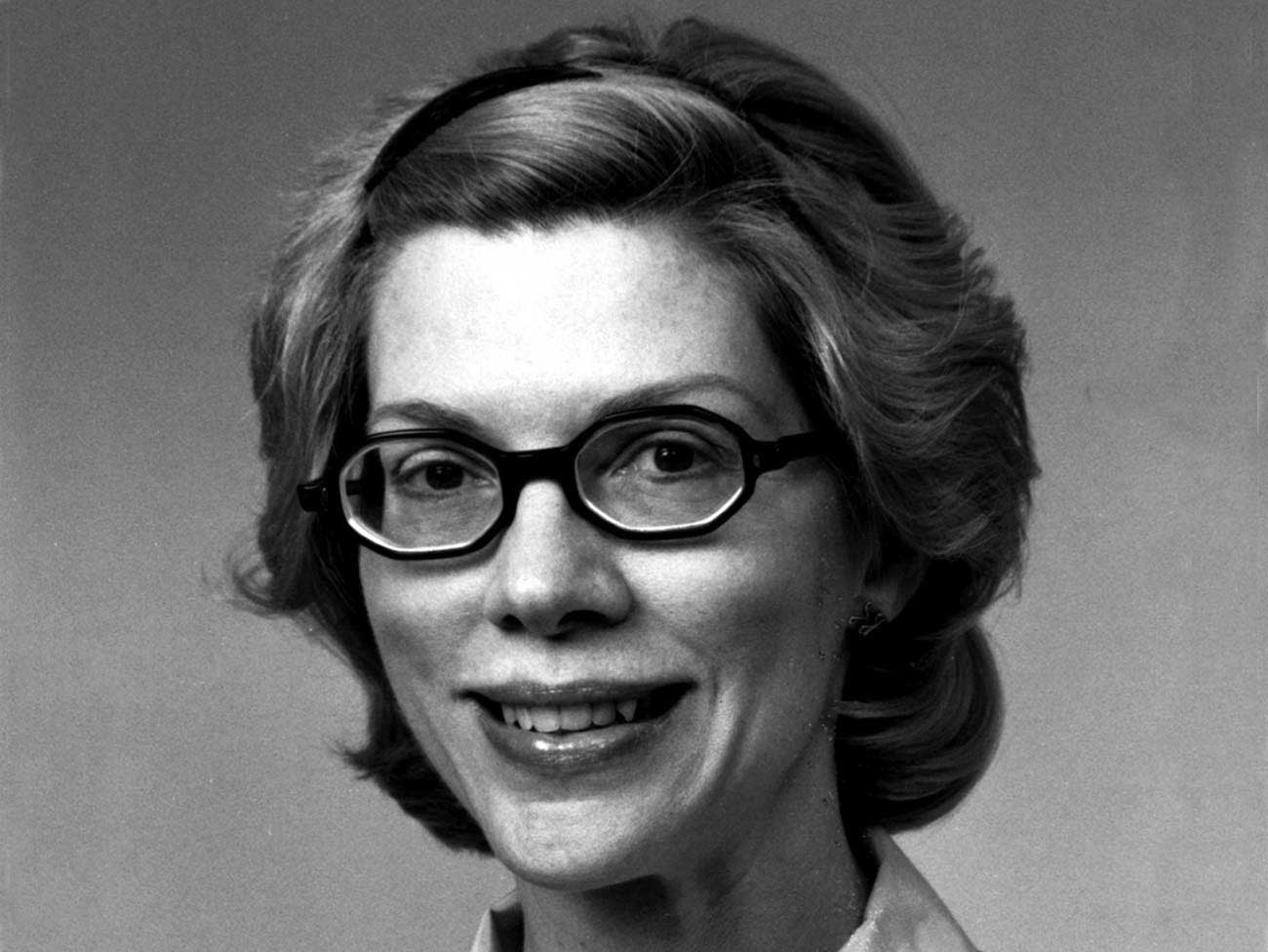

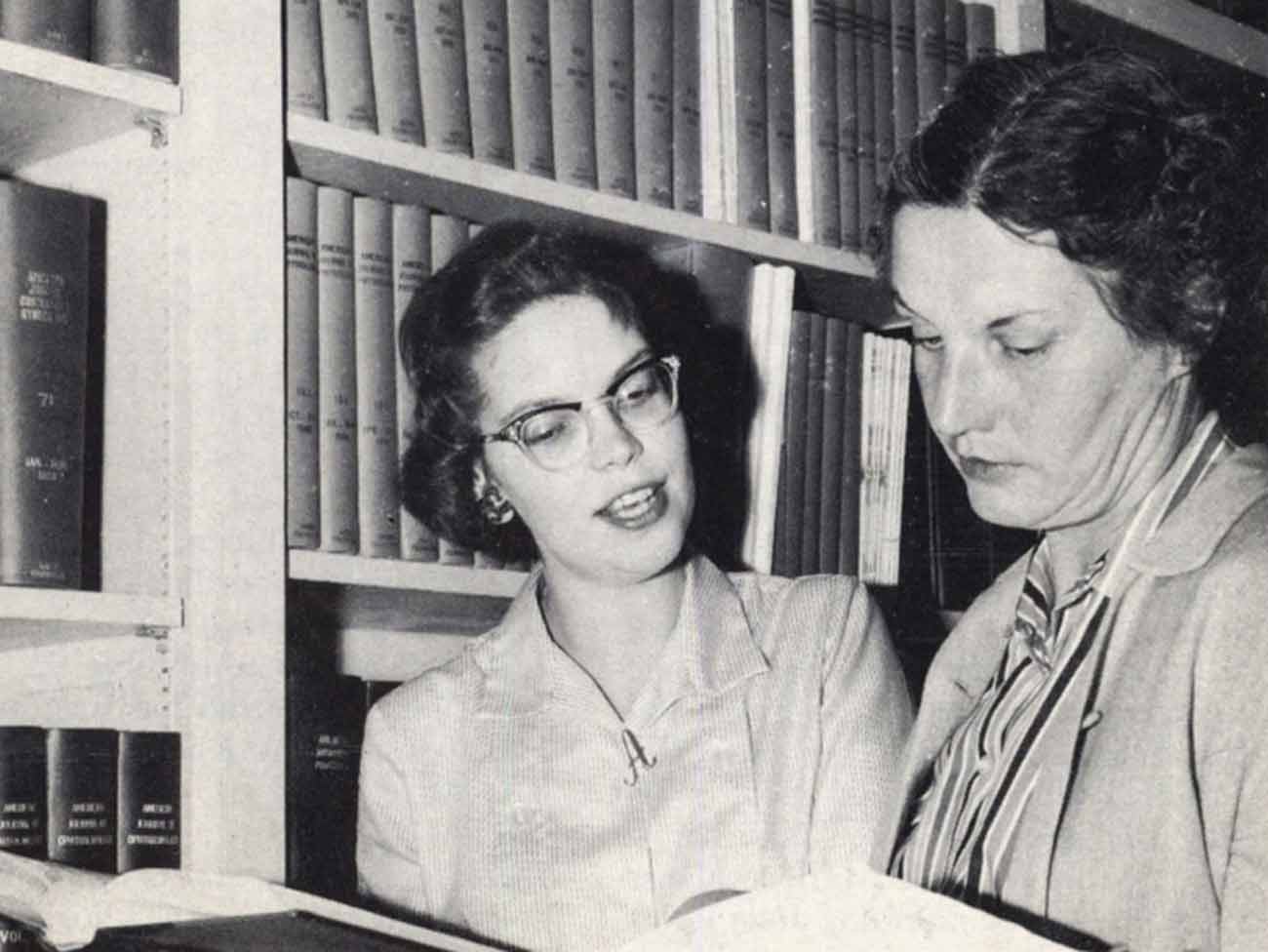

Daniels, at left, as a hospital administrator. Daniels was the first woman to serve as a hospital administrator in the Kaiser Permanente health plan.

Daniels left the school in 1953 to become administrator of the Los Angeles Permanente Foundation Hospital, making her the health plan’s first woman hospital administrator. She later returned to Northern California to take over as administrator at San Francisco Medical Center. Clair Lisker was one of Daniels’ early students who rose within Kaiser Permanente Hospital nursing administration. In a 2002 oral history, Lisker credits Daniels with “paving the way for all of us. She was in San Francisco, and she was at Sunset in Los Angeles, two major facilities.

“She was a tremendously powerful woman, intellectually. I don’t ever remember seeing her sit down,” said Lisker. Daniels encouraged her best students to earn a bachelor’s degree in addition to an RN degree, believing that a well-rounded education would ensure a promising future. Lisker was one of those students.

“Dorothea was encouraging me to go and enroll in Holy Names College in Oakland, which was then down by the lake (Merritt) where the Kaiser building is now,” recalled Lisker. “She wanted me to get the basics, like English 1A and 1B, and whatever else I needed, philosophy…I basically said: ‘I can’t afford it…she said ‘well, what I’ll do is I’ll pay your fee, and I will get reimbursed. I’ll take $5 out of your allowance (stipend) every month.’ ” Lisker remembers $5 being deducted from her stipend once but doesn’t believe Daniels ever claimed the rest of the $30 advanced ($10 per course unit).

Kind, generous, and impeccably dressed

“She was very kind and generous to those student nurses, and for a good student she would find scholarship money for that young lady to go on to get a degree, so (the student) would become a leader in nursing,” Smillie recalled. Avram Yedidia, a health plan leadership pioneer, said of Daniels: “Her dedication to patient care was as unblemished as her uniform, which miraculously never wrinkled.”

“She wore these white starched uniforms with a little pointy hat with a black band and a little pleated organdy cap on her head,” Lisker recalled, noting the cap was from the Phillips Beth Israel school. Daniels’ penchant for a proper nurse’s uniform was no doubt formed in her early years in New York. While she was at Phillips, student nurses were required to adhere to strict dress standards.

The Phillips website: “Students wore black stockings, long sleeves, bibs, aprons, ankle length blue-check dresses, tight cuffs and a bishop’s collar. During the senior year, what was black became white: socks, stockings, and dresses became the uniform of the professional nurse. Students wore no caps until the senior year.”

To make sure they got the uniform right, the administration consulted etiquette expert Emily Post on the proper attire for student nurses on an outing. “Hats and gloves were de rigueur on field trips,” Phillips historians reported.

The memory of Dorothea Daniels, who passed away in 1968, will always be of a woman to be reckoned with. Lisker summed it up: “Dorothea’s (attitude) was: ‘I’m in control. I’m in charge.’ But she also had her other (tender) side, which she didn’t display very often...She loved her dog. She brought (Snuffy) to work every day, and the dog slept in a drawer in her desk. She was a wonderful lady, but she was a character.”