Health care coverage for workers’ families didn’t come easy

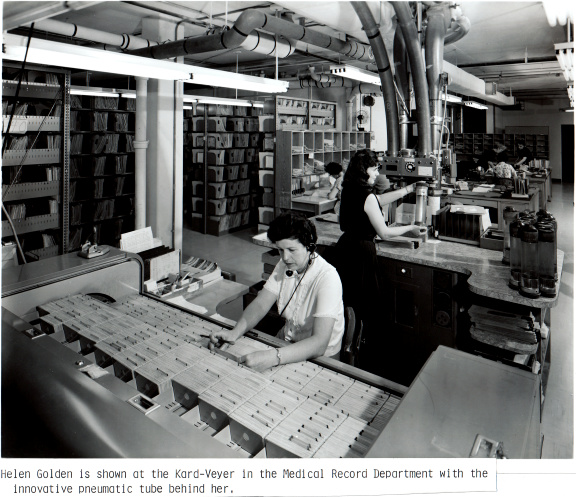

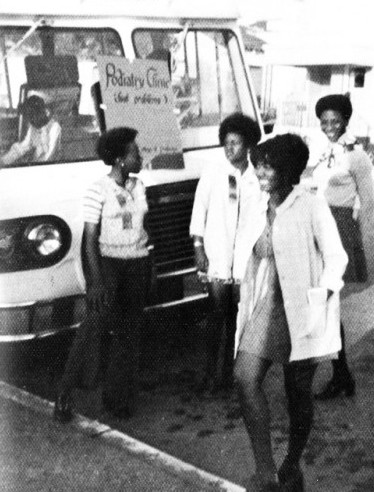

Since World War II, Kaiser Permanente's health program introduced Americans to innovative preventive medical care and health education.

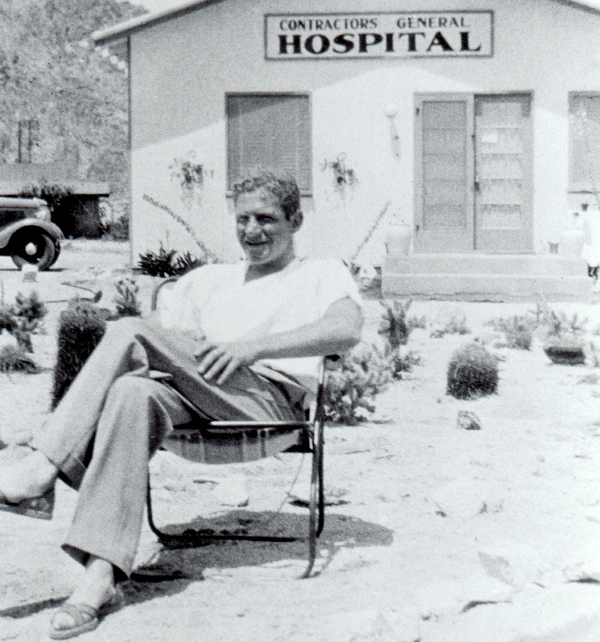

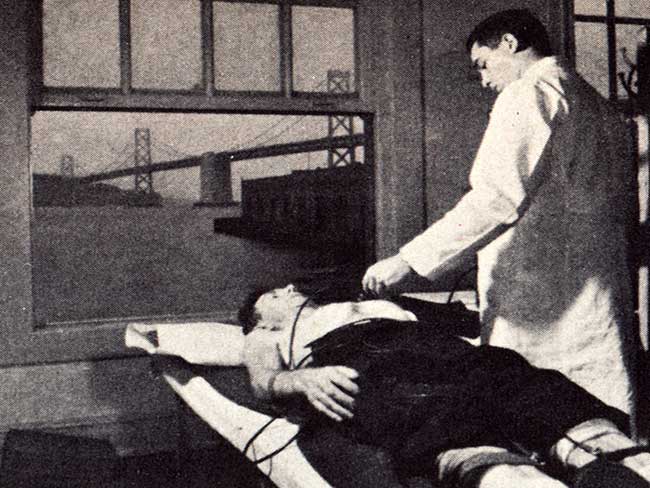

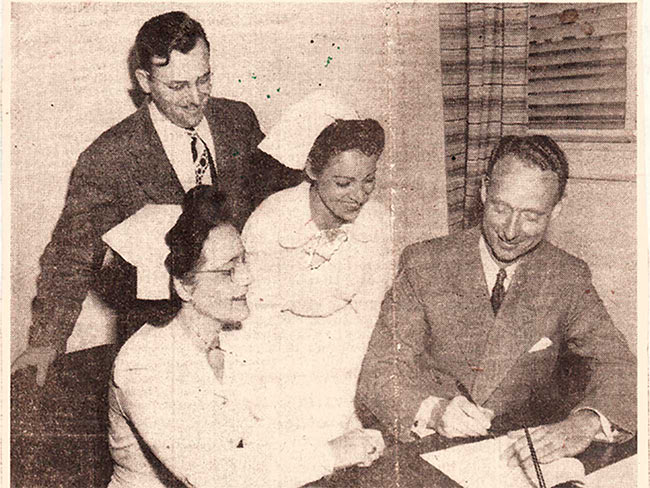

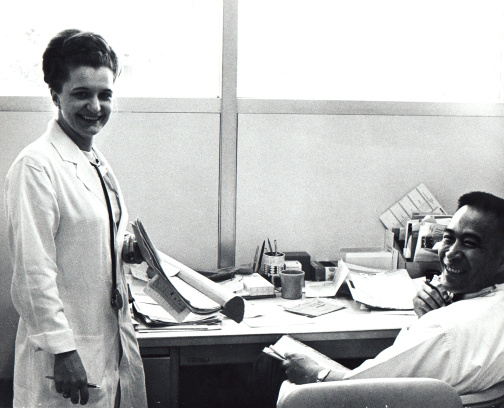

Young patient seen in Fontana Kaiser Steel plant clinic

Affordable health care was an elusive commodity in 1930s America. Medical practice was becoming more sophisticated, and qualified doctors were in great demand. Consequently, private professional care was out of reach for many Americans. Employer-sponsored health plans started to spring up in the late 1930s and early 1940s, but even those progressive prepaid plans were slow to add workers’ families to the coverage.

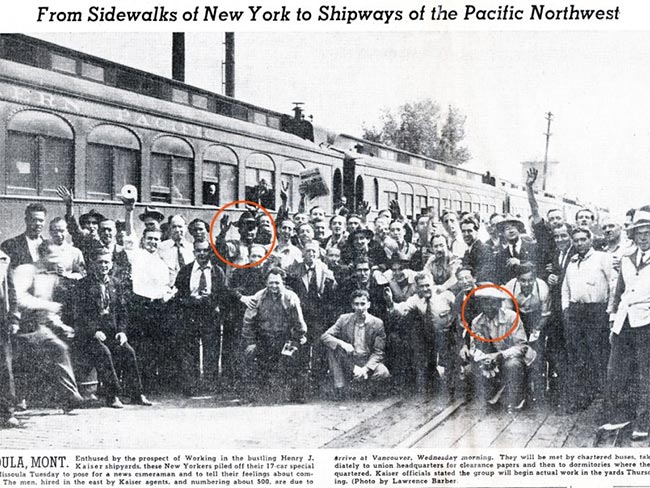

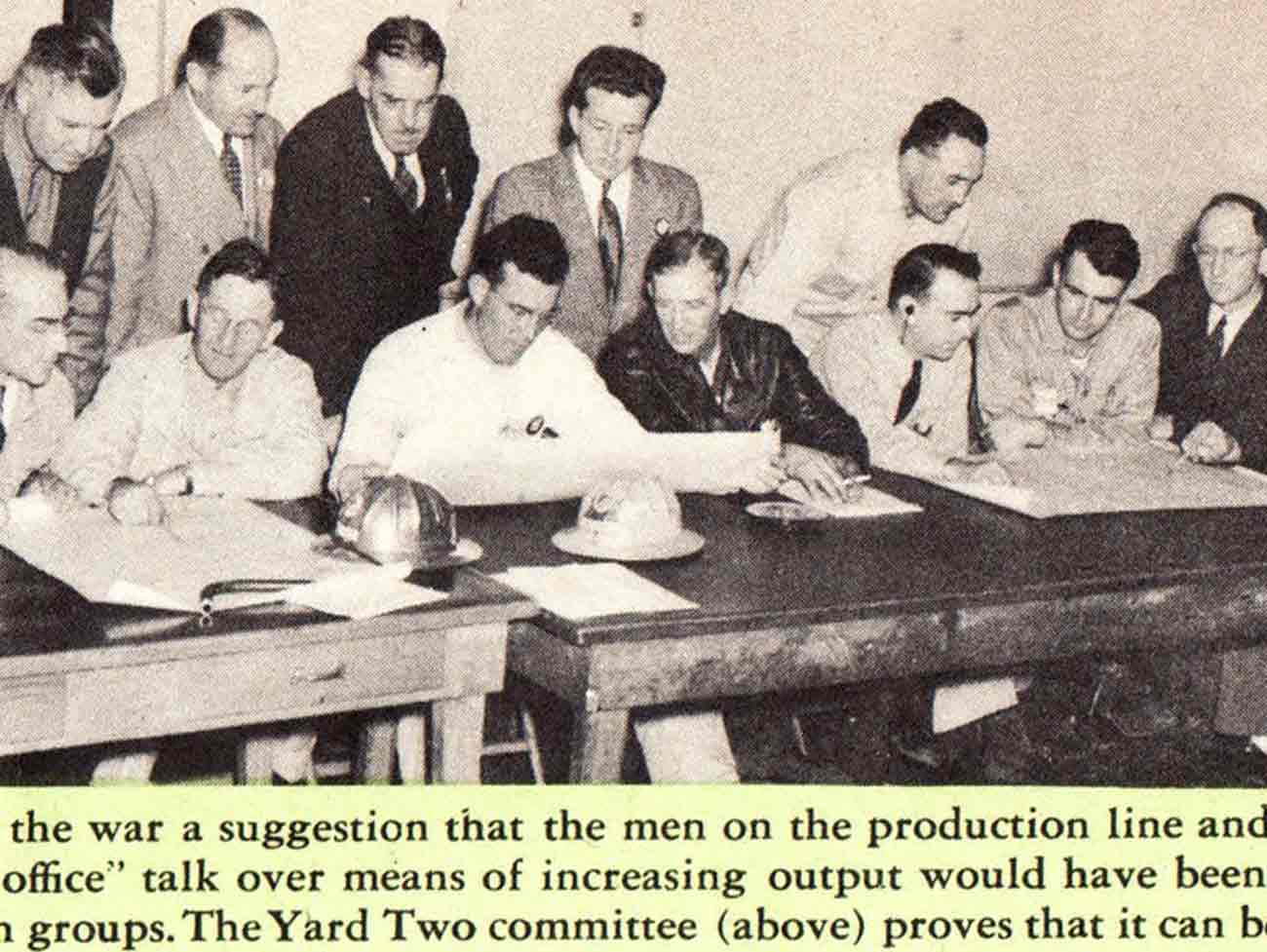

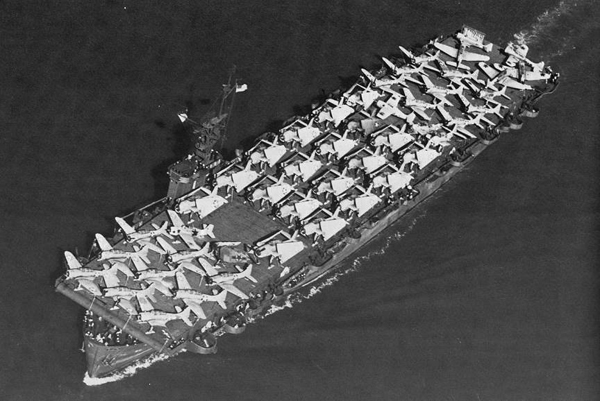

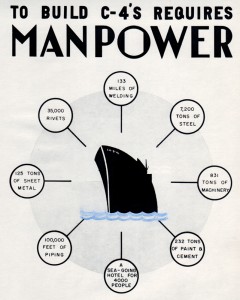

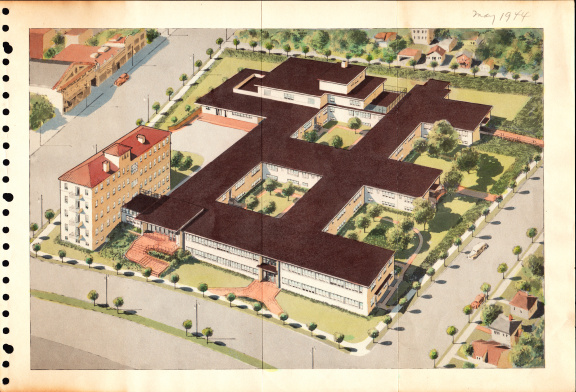

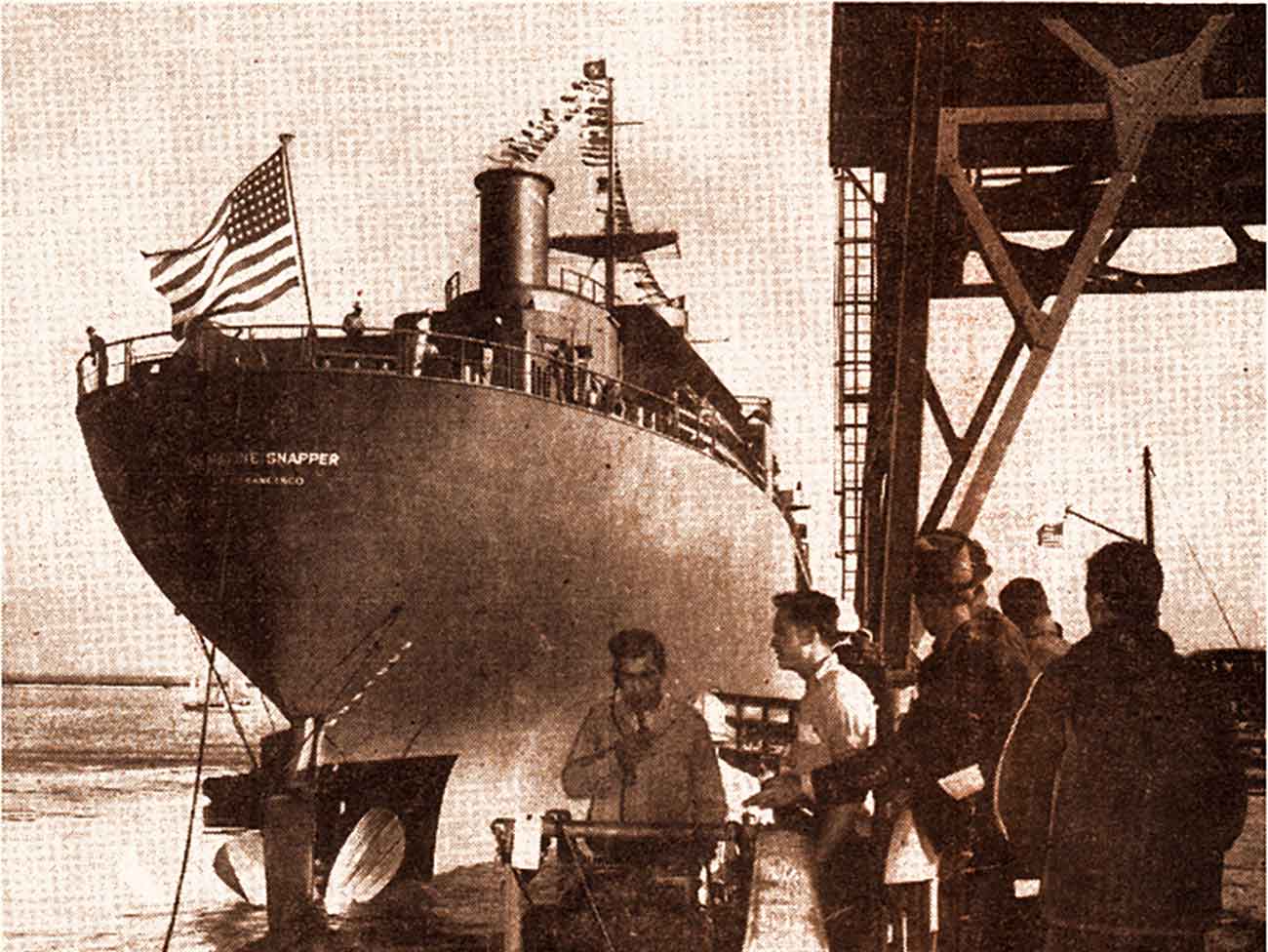

In 1944, during World War II, the issue of family health care reached a critical point on the West Coast. War industry yards and plants were frantically producing ships, aircraft, tanks and other war materiel; thousands of migrant workers and their families flooded rapidly expanding communities. Many workers were sick when they arrived, and many became injured as they worked at breakneck speed to meet production deadlines.

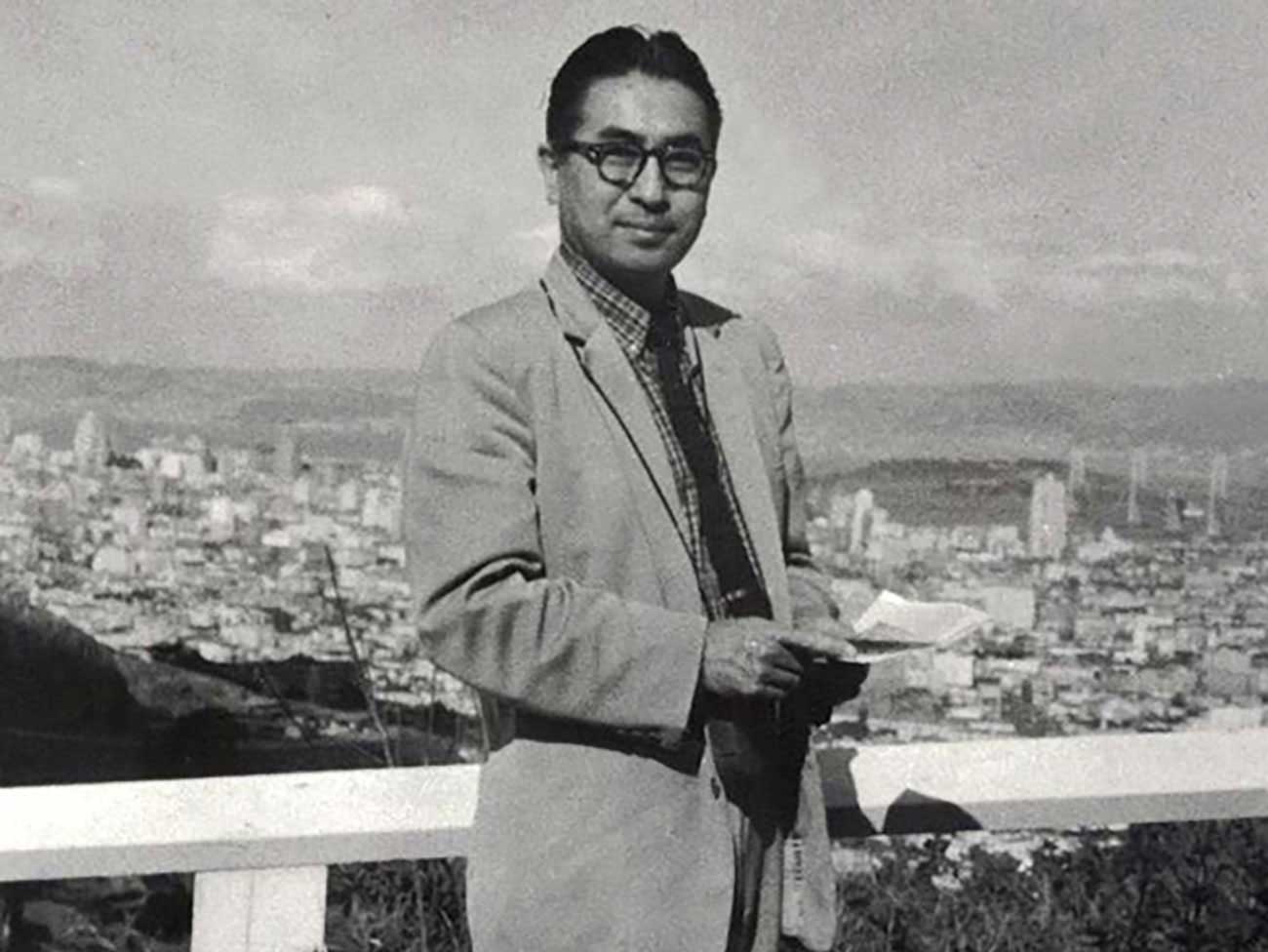

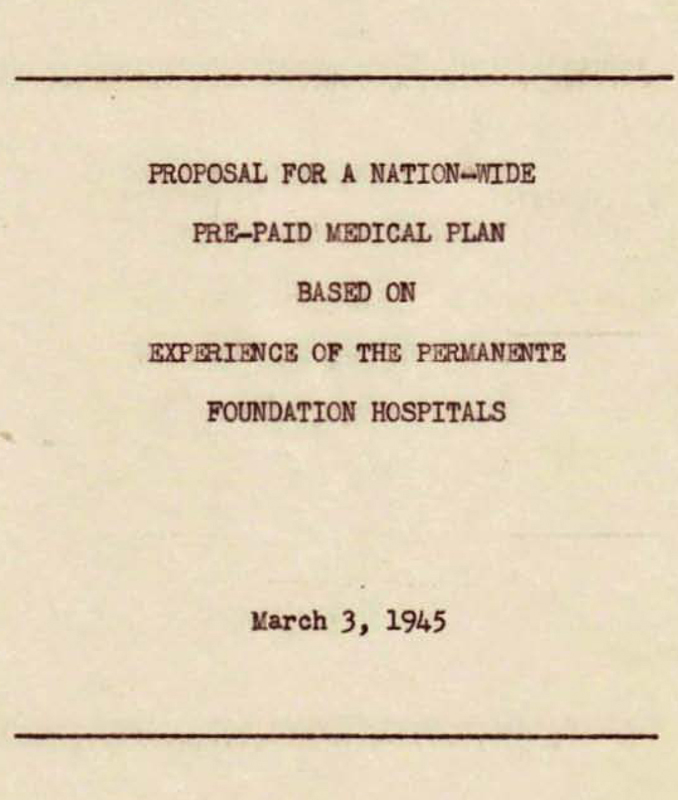

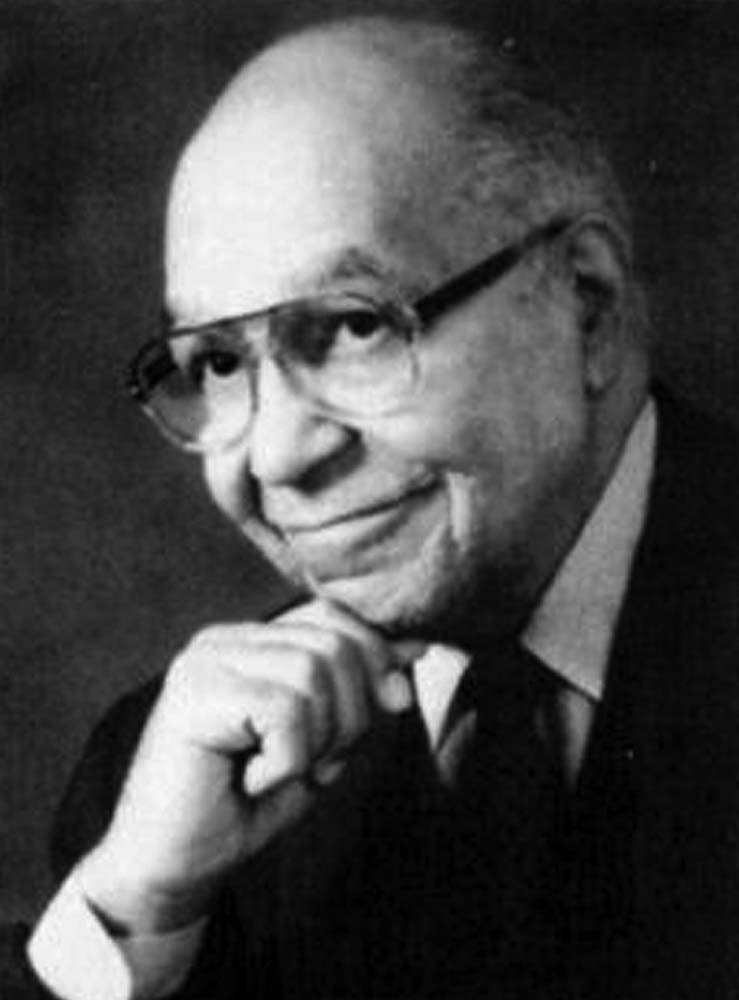

Permanente medicine, developed by industrialist Henry J. Kaiser and enterprising physician Sidney Garfield, was launched to take care of workers in Kaiser’s West Coast shipyards. The two had done this before: Garfield had set up a prepaid plan for workers on the Los Angeles Aqueduct project in 1933, and he and Kaiser had teamed up to care for workers at the Grand Coulee Dam in Washington state in the late 1930s.

The Kaiser-Garfield prepaid, group practice plan for shipyard workers was progressive and exemplary by all accounts. Unlimited medical care for the individual workers was provided for 50 cents per week. But Garfield and his doctors had their hands full, so initially only the worker — not the family members — was covered by the health plan.

Stuart Lester of “Medical Economics,” writes in the February 1944 issue: “The principal threat to the permanence of the Permanente Foundation — which provides virtually unlimited medical care for 130,000 Kaiser shipyard workers in two states* is the workers’ complaint that it makes no provision for their families.”

The article continues: “The family problem is especially acute in the shipyard town of Richmond, Calif., where the ratio of physicians to population is something like 1 to 4,000 and where the only hospital facilities of any consequence are those provided by Kaiser’s Richmond Field Hospital.”

In Richmond, Portland (Oregon) and Vancouver (Wash.), nonsubscriber family members were treated for a fee. Office visits were $2.25. For maternity, $200 covered prenatal care, delivery, hospitalization, C-section if required, postnatal care, and care for the newborn. Employees at the Kaiser Fontana steel plant in Southern California were the exception. In 1944, Fontana workers could purchase complete coverage for a family of four for $1.80 a week.

Physicians debate how to cover families

“Medical Economics” writer Lester refers to three possible solutions proposed at the time: an expansion of the Permanente plan to include family members; an expansion into the Richmond area by the California Physicians’ Services (CPS) prepaid plan as operating in other war industry communities; or the development of a prepaid arrangement for families through a private physician network.

The California Medical Association (CMA) launched the CPS in 1939 to offer prepaid care to low-income families in California. Initially, the physicians association’s plan offered a “full coverage contract” that included all outpatient physician services. In 1942, CPS excluded the first two doctor visits from coverage to make the plan financially viable, according to the April 1943 issue of the CMA’s “California and Western Medicine.” In 1943, CPS, the precursor to Blue Shield, had 39,000 commercial members, 5,100 government rural health program subscribers and a total of 32,000 war housing resident members in Vallejo, Marin, Los Angeles and San Diego.

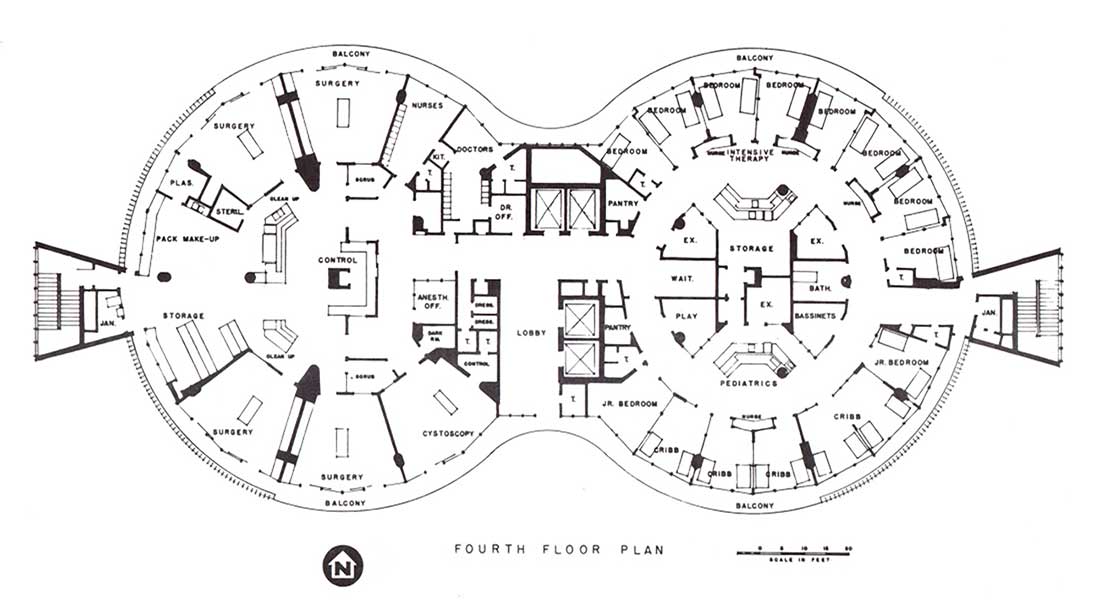

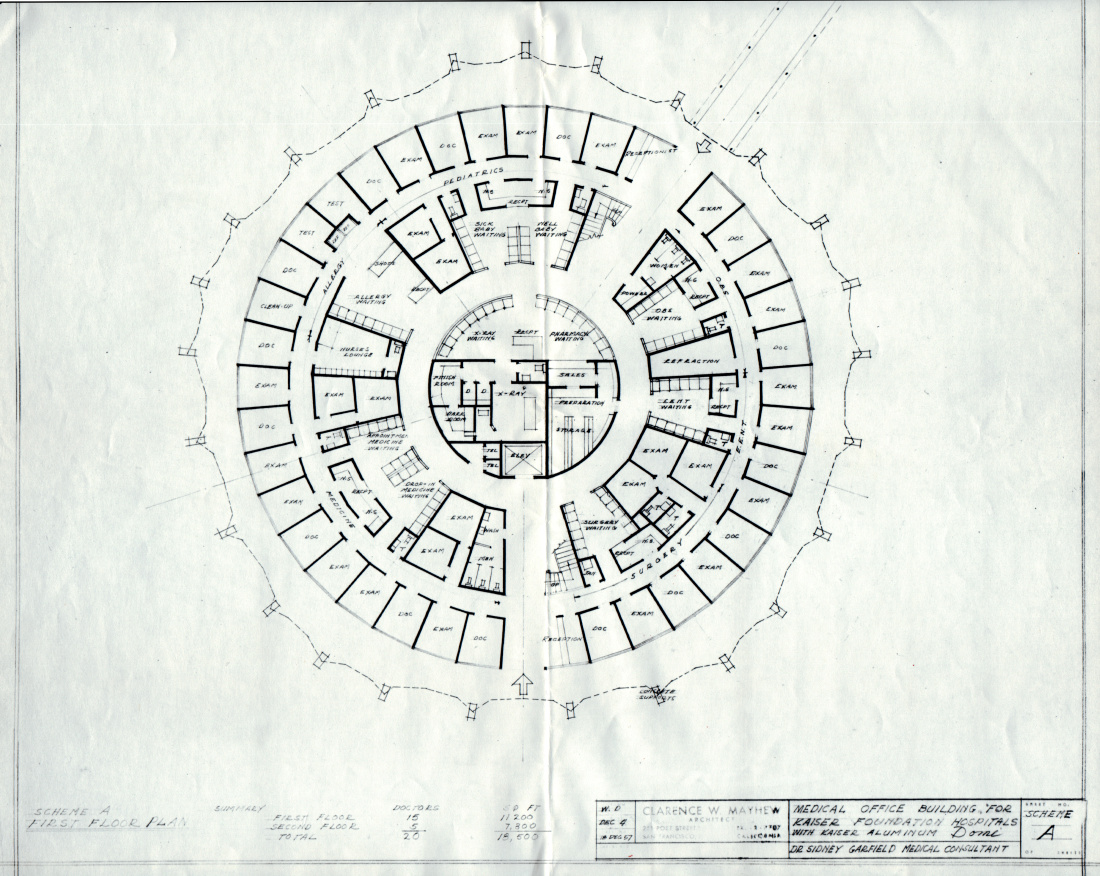

“Dr. Sidney R. Garfield, Kaiser’s medical director, sees two obstacles to an extension of his program to include families: One is opposition by the local medical societies. The other is lack of facilities — particularly in the hospital at Richmond,” Lester wrote in “Medical Economics.” The article noted that expansions of the Richmond Field Hospital and the Permanente Foundation Hospital in Oakland were under way.

The second proposal — having CPS provide family coverage for Richmond area workers — had been tried previously and failed. In 1942, CPS had offered a family plan in nearby El Cerrito and was not able to attract enough members. The coverage for non-Kaiser workers was enticing: a $5 flat fee no matter how many family members. It wasn’t practical for Kaiser employees, however. To take advantage of the CPS plan, a worker would have to buy his or her own coverage for $2.16 a month and then pay $5 for the rest of the family.

According to the “Medical Economics” article, solving of the family care issue by fee-for-service doctors was doomed from the beginning. A shortage of private doctors and inadequacy of medical facilities made any such plan unfeasible. Also, California private practice physicians were admittedly just tolerating the Permanente model of prepaid, group practice with salaried physicians. One private doctor told the magazine: “The Kaiser-Garfield groups are doing a job right now that is aiding the war effort, and are doing it well. But we don’t like their system.”

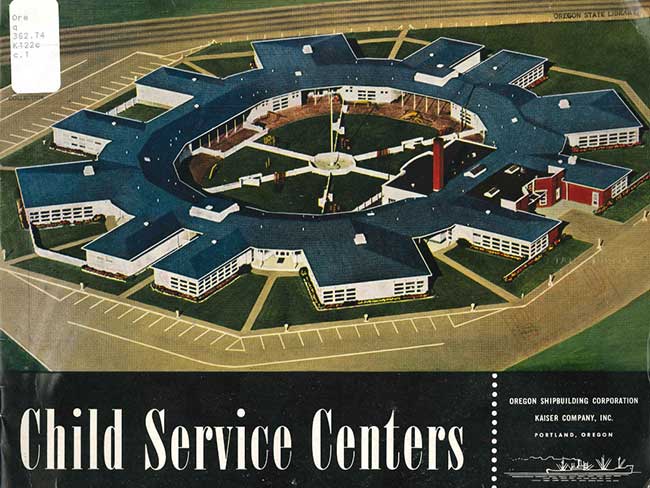

Kaiser extends coverage to shipyard families

In the spring of 1945, the Permanente medical plan, now with expanded facilities to accommodate more members, was extended to the families of all Kaiser shipyard workers. “Medical Economics” reported the details of the Permanente family care plan: for $117 a year ($2.25 per week) for a family of four, coverage was extensive. It included 111 days of hospitalization, complete diagnostic services, necessary drugs, physician services at home or medical office, major and minor surgery, and ambulance service within a 30-mile radius. Members paid an extra charge of $60 for comprehensive maternity care, $15 for a tonsillectomy and $2 for a house call.

"Medical Economics" concluded the article with this statement: "Insurance men pointed out that the total annual cost for a family of four, $117 a year, is an amount which has generally proved to be too high for any wide participation on a voluntary basis."

Workers who left the shipyards could maintain coverage for a “slightly higher” premium as long as they continued to live in the service area. This retention provision foreshadowed Kaiser and Garfield’s plans to keep the Permanente medical care plan alive after the war industries shut down.

*Kaiser shipyards health plan actually took care of workers in three states, California, Washington and Oregon, and enrolled up to 190,000 members at the peak of the war.