Permanente physicians strive to prove high quality of care

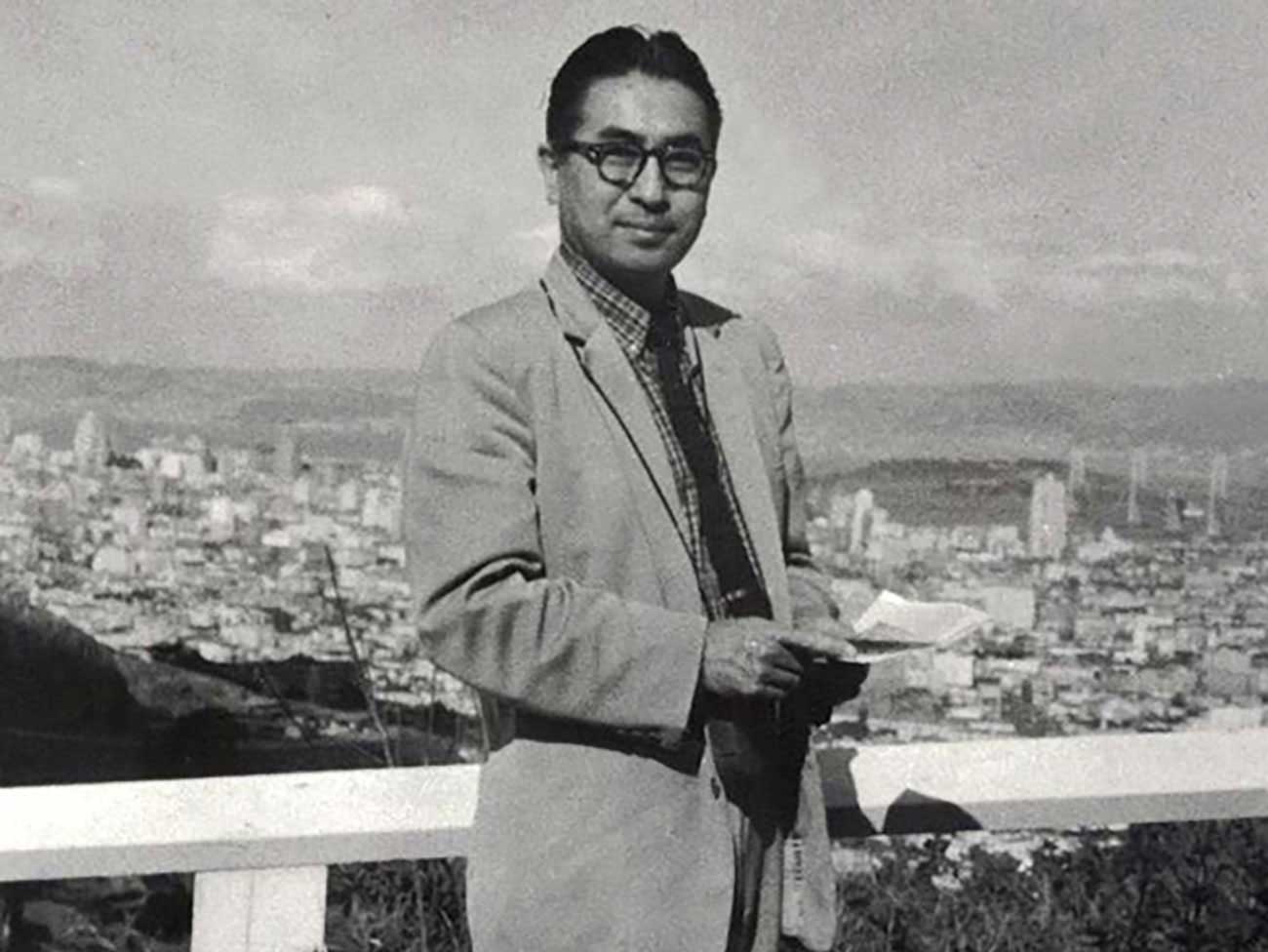

Early nation-wide health care quality assessments and evaluations became inefficient, leading Dr. Sam Sapin to pioneer a new program.

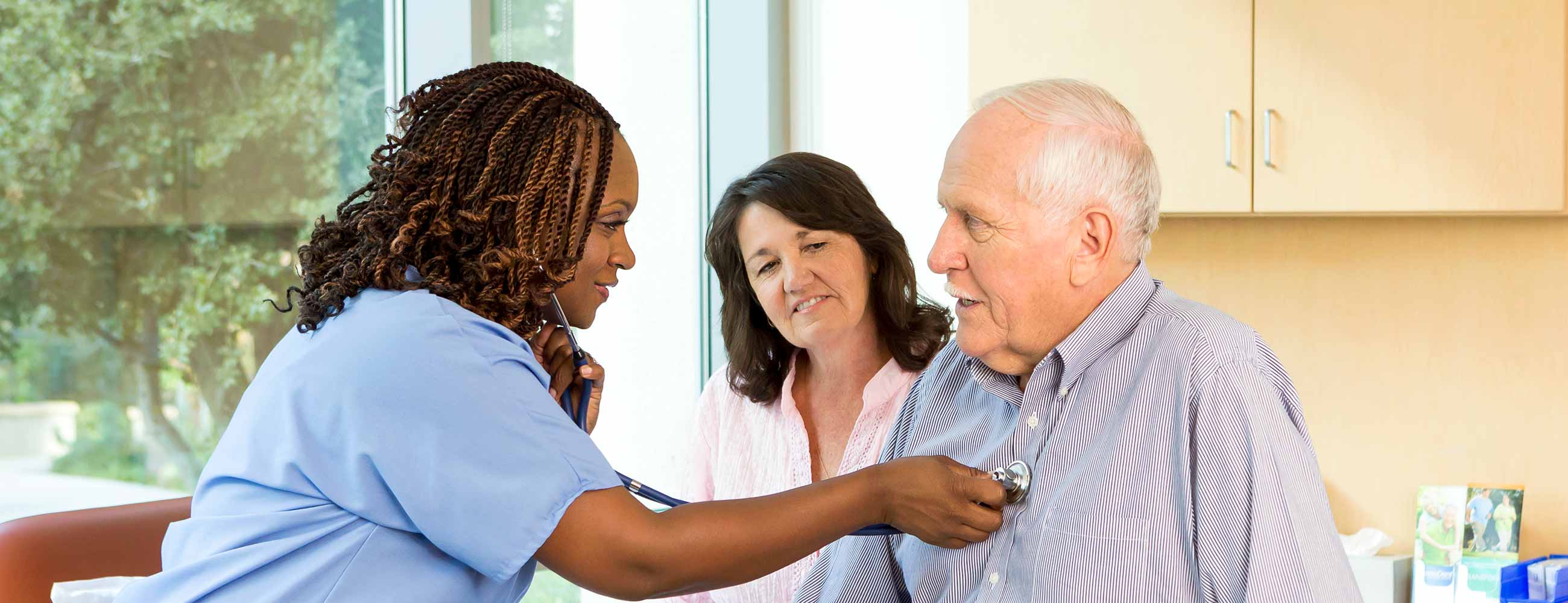

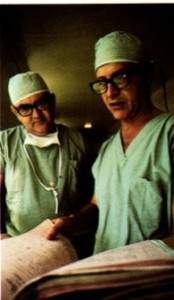

T. Hart Baker, MD, medical director of the Southern California Permanente Medical Group, and William D. Finkle, Ph.D of the Economics and Statistics Department, review quality data. 1973 Kaiser Permanente Annual Report photo

By the late 1960s, Kaiser Permanente physicians were pretty confident about the quality of care they were providing to the health plan’s growing membership. Although they were the target of unfair quality jabs by competing fee-for-service physicians, the Permanente Medical Groups in all regions had been validated in objective studies assessing medical care.

The National Advisory Commission on Health Manpower inspected Kaiser Permanente operations and reviewed patient charts at program facilities in both California regions in 1967. The commission concluded: “The quality of care provided by Kaiser Permanente is equivalent, if not superior, to that available in most communities.”

Further validation came from a University of Michigan study of quality of care in Hawaii in 1969. Under the auspices of the Hawaii Medical Association, local specialists set up criteria for review of care. “The study indicated that care at Kaiser Foundation Hospital and by the Hawaii Permanente Medical Group were both substantially above the island (Oahu) average and among the best in the study,” B. L. Rhodes, MD, executive vice president and manager of operations, reported to the board of directors in 1983.

Despite the praise, quality was becoming a big issue

Such kudos didn’t really solve the quality issue for Kaiser Permanente. By the 1970s, it seemed as though every government agency, professional association, and consumer group (and their brother and sister) wanted to get into the quality assurance game. This is where it started to get complicated.

“There was a quality frenzy in the '70s,” noted Sam Sapin, MD, an early Southern California Permanente physician and quality pioneer.

The year 1965 brought Medicare and Medicaid, programs enacted by Congress to provide medical care for the elderly and poor. Naturally the federal government, now pouring millions of dollars into health care for these populations, wanted a way to ensure the care was good.

This interest resulted in an amendment to the Social Security Act setting up Professional Standards and Review Organizations to monitor utilization and quality of care. Also in 1965, the Illinois Supreme Court ruled that hospitals are accountable for their doctors’ mistakes, a concept validated for California hospitals in subsequent court rulings.

In 1972, the California Medical Association, or CMA, which accredited medical education programs, began requiring retrospective medical records audits to assess the quality of care and to identify issues for continuing medical education programs.

The CMA adopted a medical audit system developed in 1956 by Paul Lembcke, MD, a New York quality evaluation pioneer and epidemiologist. The Lembcke method called for reviewers to select a topic arbitrarily and then review medical records of patients with that diagnosis after discharge from the hospital. Certain objective standards or criteria had replaced the subjective review by physicians.

Other agencies followed the CMA. The Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Hospitals adopted the same style of medical audit as a condition of accreditation. The American Hospital Association adopted a similar audit program. In 1973, the federal government widened its scope of quality review by including Lembcke-style medical audits as a requirement for designation as a qualified HMO, or health maintenance organization.

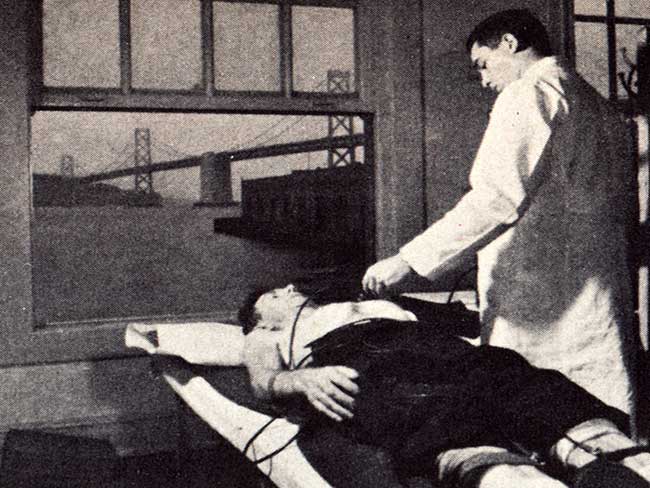

Honolulu Kaiser Permanente physicians developed their own medical audit system in 1969. Here Clifford J. Straehley, MD, chief of surgery, right, and Raymond D. Stoneback, MD, chief of anesthesiology, discuss surgical audit data. 1973 Kaiser Permanente Annual Report photo

Clifford J. Straehley, MD and Raymond D. Stoneback, MD discuss surgical audit data, 1973

Widely used and accepted medical audit falls out of favor

The medical audit adopted by everyone turned out to be wrongheaded, inefficient, and expensive and was eventually abandoned. However during the 1970s, Kaiser Permanente had to perform such audits to keep its quality reputation intact.

“We all followed the Pied Piper,” Sam Sapin offered in a talk to the Kaiser Permanente board of directors in 1983. “The land was alive with auditing and auditors. A whole new profession of medical records analysts was created and millions and millions of dollars and countless hours were spent on auditing,” Sapin laments.

For the next almost 10 years, Sapin, in Southern California, and quality people in all Kaiser Permanente regions would bow to the almighty medical audit, even though its effectiveness turned out to be a mirage. Sapin, appointed in 1972 as the first Southern California Permanente Medical Group director of Education and Research, lived and breathed quality audits. It was his job to set up a quality assurance program for all Kaiser Permanente facilities in the south, a daunting charge.

Kaiser Permanente regional quality reviews begin in 1973

Beginning in 1973, Sapin coordinated a quality assurance program with six Kaiser Permanente Southern California hospital staff who agreed on the same diagnosis to audit. Sapin and Southern California Permanente Medical Group medical director T. Hart Baker, MD, obtained a 3-year federal government grant to conduct studies for the Experimental Medical Care Review Organization, or EMCRO, program, which dovetailed perfectly with Sapin’s auditing efforts.

Baker, Sapin and others published SCPMG’s findings in “Quality of Medical Care: Research in Methods of Assessment and Assurance” in 1978. The EMCRO report detailed the use of the Lembcke method and noted its flaws. Later, Sapin would judge the audit method too expensive for its value:

“We subjected the medical audit model to rigorous study. We learned from these experiences, along with the rest of the country, that the audits we were instructed to do were not making any significant impact on the quality of care.”

Sapin also called out the difficulty in adopting criteria. “Physicians argued for hours about them, partly because most of the things we do to and for patients have never been scientifically validated. Every physician thinks he or she is doing the right thing in the right way and there is usually insufficient evidence to prove one right or wrong.”

Meanwhile, Leonard “Len” Rubin, MD, PhD, Kaiser Permanente Northern California’s quality assurance leader, was developing an auditing method of his own. Joining Kaiser Permanente in the 1950s, Rubin had a strong interest in quality measurement and began working in the late 1960s on an alternative to the mandated medical audit.

Sapin joined Rubin in his refining of a new audit methodology that would review patient care before discharge and only focus on identified problems.