Permanente pioneers step out to blaze their own quality trail

Dr. Leonard Rubin and Sam Sapin pioneered and piloted new quality assessment methods, creating the foundation for assessing today's quality of care.

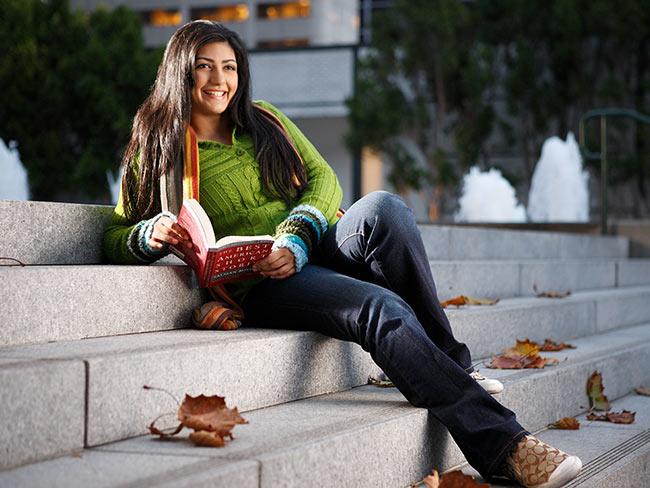

Leonard Rubin, MD, Northern California quality expert, and Sam Sapin, MD, his Southern California counterpart, go over charts. Kaiser Permanente 1986 Annual Report photo

As the 1970s drew to a close, physicians and quality reviewers nationwide were probing and struggling to make a faulty “medical audit” system work to evaluate and improve the health care of millions of Americans, young and old, well and sick, rich and poor.

In three Kaiser Permanente regions, physicians and quality auditors had received federal grants to apply the medical records retrospective review or traditional method endorsed by state medical associations, the Joint Commission for Accreditation of Hospitals (JCAH), and Medicare and Medicaid officials.

Southern California, Hawaii and the Northwest Kaiser Permanente regional medical groups obtained three-year grants under the EMCRO (Experimental Medical Review Organizations) project to put the traditional medical audit system into practice and find out how well it worked. It didn’t.

‘Quality assurance is a kind of umbrella to keep the environment safe for the patient’ — Mike Chappin, MD, Hawaii Permanente physician, Kaiser Permanente employee magazine, Spectrum, winter 1987

Northern California quality pioneers forge their own model

In Northern California, quality guru Len Rubin, MD, PhD, had taken a different path. “I think they (Northern California) were a bit smarter than us (SCPMG),” admitted Sam Sapin, MD, Kaiser Permanente Southern California quality leader in the 1970s and 1980s.

As early as 1973, Rubin was piloting a new quality assessment method in all 13 of the Northern California Kaiser Permanente medical centers. Rubin’s system, called Comprehensive Quality Assurance System (CQAS), had reviewers checking medical records of patients who had just been discharged from the hospital. The emphasis was on finding deficiencies in real time and auditing problem cases for questionable practices that may have contributed to bad outcomes.

“He (Rubin) really pioneered the problem-focused approach to quality of care assessment and assurance,” Sapin said. “His motto was and is, “Find out what’s wrong, not what’s right, then fix it.” Rubin published his CQAS protocol in 1975 for the American Group Practice Association.

Best to measure process or outcome?

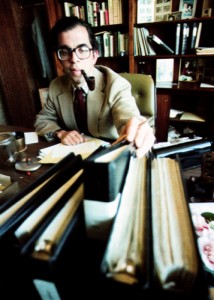

Joel Kovner, a doctor of Public Health and director of the Medical Economics Department for the Kaiser Permanente Southern California region, was a key player in quality assurance research.

In developing his model, Rubin was acutely aware of the difficulty of defining the relationship between the process — delivery of care and drug administration — and the outcome of those treatments. Rubin argued that there are many “outcomes” in the continuum of care and many factors don’t affect the ultimate outcomes of good health, ability to return to work, or at the other end of the spectrum death or chronic illness or disability.

“As can be seen, there are endpoints here (or outcomes) relating to many departments (laboratory, record room, physician, pharmacy, patients, etc.). Often the outcome of one process is the input for another,” Rubin wrote in his 1975 CQAS publication.

“Further confusion lies in the time-dependence of the outcome. The outcome may differ enormously, depending upon whether it is being measured immediately after treatment, several months after treatment, or several decades after treatment,” he continued. “Latent drug effects only now becoming known completely invalidate previous judgments that some outcomes were good in the long term. He concluded: “There is no way to measure ‘ultimate outcome.’”

Different schools of thought cloud issue

Sapin reported that at this time debate was raging between the “outcome” and the “process” people. “The process people say outcomes are too difficult to measure and interpret correctly; one should only compare outcomes of cases of comparable severity and one should also take into account all of the intervening variables (e.g. patient compliance, income level, lifestyle) which cannot be controlled by the provider and yet will affect the outcomes.

“On the other hand, the outcome people say don’t bother to assess process because many processes do not correlate well with outcomes and some may even lead to bad outcomes. The safety and efficacy of many of the things we do to and for patients have never been scientifically validated,” Sapin said in his 1983 presentation to the Board of Directors, “Historical Perspectives on Quality of Care.”

In 1973 as Rubin tested and refined his method, Jim Vohs, Kaiser Permanente’s CEO, set up the Kaiser Permanente board of directors’ Subcommittee on Correlation of Quality of Care and established a new department to focus on quality. Vohs also established the Interregional Quality Assurance Committee (IRQAC), with quality representation from all Kaiser Permanente regions.

Rubin’s system had an almost twin at the state level

Ironically, in the early 1970s the California Medical Association (CMA) and the California Hospital Association (CHA), responding to the rise of malpractice insurance rates, devised a “problem-focused” or “generic-screening-criteria” method similar to Rubin’s. Even though both agencies required the traditional medical audit for their member organizations, they decided to use a different method to identify outcomes that could become subjects of malpractice lawsuits.

Ohio Permanente physician Sam Packer examines a young patient. Physicians in all regions began participating in quality efforts in the 1970s.

The CMA-CHA method called for the review of medical records upon a patient’s discharge to identify adverse outcomes. In reviewing charts, they measured quality according to 20 standards to find problems. Examples of the screening criteria were unplanned removal of an organ, a repeat of an operation during the same hospital stay, and development of a heart attack after admission. CMA-CHA’s “Medical Insurance Feasibility Study” was published in 1978.

By 1980 the traditional medical audit had become a dinosaur in the world of quality assessment and assurance in favor of a problem-focused method.

In 1980 JCAH quietly abandoned the traditional medical records audit. JCAH’s new published standards required hospitals to have a documented quality assurance program but no specific audit program was mandated. Members of the federal Professional Services Review Organizations (PSROs), local agencies designated by Medicare and Medicaid to study quality of care, were also disappointed by the medical audit results and phased out the method.

In its 10th anniversary issue in 1984, the JCAH journal re-published Sapin’s 1980 groundbreaking article, “A Region-wide Quality of Care Monitoring and Problem Delineation Plan.” The article authored by Sapin, Gerald Borok, MPH, and Cheryl Tabatabal, rejected the traditional medical audit and described the problem-focused review scheme he and Rubin had developed and piloted.

In a 10-year anniversary reflective commentary, William C. Felch, MD, Quality Review Bulletin Editor and New York internist, recognized the new Kaiser Permanente-generated system and touted the plan as “ambitious, carefully thought out and planned.” He added: “The question five years later is how did it all work out?”