Nurses begin quest for professional recognition after World War II

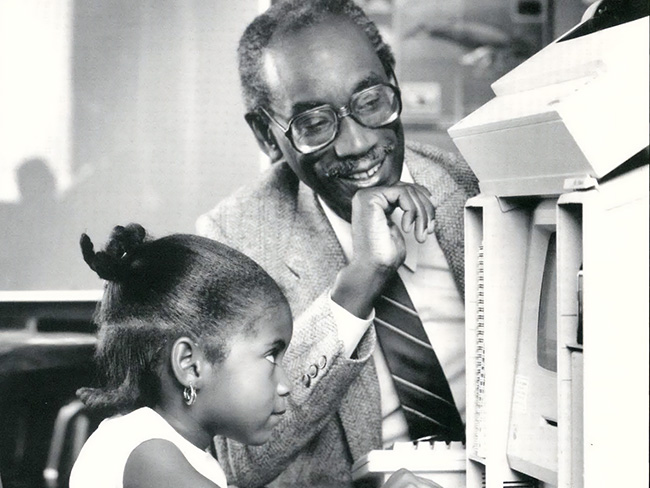

Co-founder Dr. Sidney Garfield makes history by signing the first nurse contract with the Nurses' Guild.

Nurses pose on the lawn of the Permanente Oakland hospital during World War II

Having played a significant role in the Second World War, trained nurses came home in 1945 expecting to be given the respect they earned in the armed forces. Many women had distinguished themselves by saving lives in combat zones, and many achieved the rank of officer.

Like other underappreciated groups who came home to a seemingly unchanged society, nurses were discouraged and hesitated to pursue their chosen profession due to low pay, low status and poor working conditions. Many nurses chose to be waitresses or factory workers where they could make more money and work more reasonable hours. The exodus from the nursing profession created a shortage of qualified nurses, which would intensify in later years.

Home-front nurses had been content to work without making demands during the war emergency. But after the war, they wanted more. Alameda County nurses had affiliated with the California State Nurses Association (now California Nurses Association or CNA) in 1941 and relied on the association to represent them to East Bay hospitals administrations. But in 1945 these nurses realized that the statewide association had not been effective in bringing them better pay and working conditions.

The association had developed employment guidelines for the benefit of nurses, but the association had no power to force hospitals to follow the voluntary rules. The East Bay Hospital Conference, made up of administrators from 12 hospitals, adopted a “Statement of Policy” regarding nursing issues in 1941, and dropped it after the war emergency was over.

Alameda County nurses form their own guild

Major Edith Aynes, a recruiter from the Army Nursing Corps, gave force to the East Bay nurses’ argument that their profession deserved a better status. Quoted in the San Francisco Chronicle in 1946, Aynes spoke about the military model of the registered nurse as someone who performed patient care, while other untrained staff performed peripheral menial tasks.

“Instead of taking temperatures, serving (food) trays, making beds and carrying bath water, the nurse is free to change dressings, give medications, care for sick patients and in general supervise the entire ward,” Aynes said.

Alameda County nurses took Aynes’ message to heart and decided to form their own nurses union in November of 1945. “The objective of the guild will be to establish standards relating to salaries, personnel practice and conditions of employment and to maintain an economic security program for registered nurses, members of the guild,” Kathleen Koepke, president of the guild, told the Oakland Tribune.

In March of 1946, the guild asked the U.S Conciliation Service to recognize the guild as bargaining agent for the nurses in negotiations with the East Bay hospitals. In April of 1946, guild members voted to affiliate with the Public Workers of America (PWA) and the CIO (Congress of Industrial Organizations), a federation of unions. This was at the same time the CIO and AFL (American Federation of Labor), then separate groups, were fighting in Sacramento over political endorsements for state offices.

Guild appeals to public for support

Soon after joining the CIO, the guild began a public relations campaign to win community support for their demands for better pay and working conditions. “You Needed the Nurse…Now the Nurse Needs You” was the title of the pamphlet the new Nurses’ Guild of Alameda County’s leaders developed and delivered to 8,000 trade unions, teachers, doctors, dentists and other professionals in Alameda County.

In the pamphlet, the nurses laid out their demands: “The immediate goal of the Nurses’ Guild is a collective bargaining contract that will guarantee the nurses a decent wage, reasonable amount of leisure, and fair working conditions …living symbols of our American Way of Life. Standing united, the nurses are determined that, no matter how long it takes, the hospitals must finally recognize the justice of the nurses’ case by signing the contract.

“The nurses’ requests are for your protection!” the pamphlet declared, appealing to the public’s self interest in quality care. Specifically, the guild was asking for a better salary (minimum of $200 a month), a 40-hour work week, down from the standard 48-hour week for nurses, designated holidays, vacation with pay, reasonable sick leave with pay, adequate maternity leave, pre-employment and annual health examinations, protection under the Social Security Act and protection under the Unemployment Insurance Acts. The nurses also demanded the right of collective bargaining through “organizations of her own choosing without discrimination or intimidation and a job as an American Citizen, regardless of race, religion, color, ancestry or national origin.”

The guild leadership invoked the words of a prominent economist of the time, Varden Fuller, to bolster their case: “There will be no real end to the shortage of nurses in Alameda County until nurses can be guaranteed decent working conditions in hospitals,” Fuller was quoted in a guild press release. “It’s no wonder that so small a percentage of nurses coming out of the armed forces are returning to hospital work. A nurse can go to work in a warehouse or a cannery and earn as much or more money as in a hospital.” The nurses augmented that claim in the pamphlet, declaring that a woman paring and peeling in a cannery made $202.50 and a grocery clerk made $241 per month, while nurses were making $175.

Chief physician Sidney Garfield makes history by signing first nurse contract

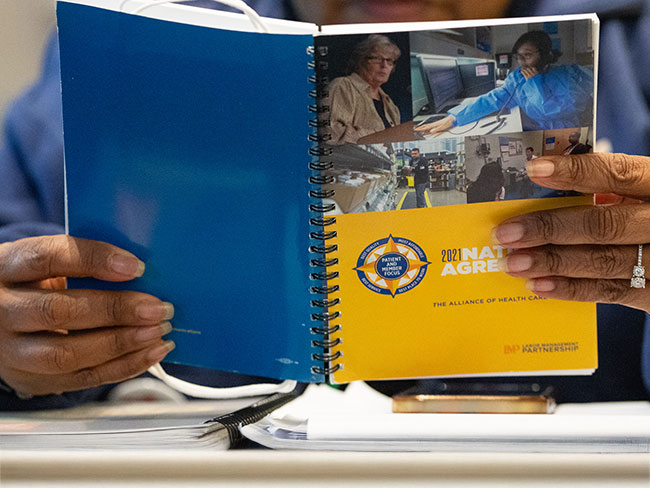

The Nurses’ Guild leaders urged the public to write to the hospitals and “let them know you’re in complete sympathy with the nurses’ just requests.” On the list of hospitals whose nurses had voted to be represented by the guild was the (Kaiser) Permanente Foundation Hospital at Broadway and MacArthur in Oakland, the first Permanente hospital, opened in 1942. Permanente administration distinguished itself by being the only hospital representatives that allowed a secret ballot for its nurses to select an organization to speak for them in labor negotiations. Sidney Garfield, MD, Permanente’s founding physician, was also the first to sign a collective bargaining contract with the newly energized nurses’ organization.

The nurses’ initial campaign for labor representation came to a close on August 1, 1946, with the announcement of Garfield’s signing. “Permanente’s historic contract gives working nurses a 40-hour work week for the first time in Alameda County hospitals,” the Guild press release stated. “Besides reducing the former 48-hour work week to 40 hours, the Permanente agreement raises the former basic wage of $175 to $185. The basic rate will go up to $190 on October 1 and $200 monthly on January 1, 1947.” Meanwhile, the California State Nurses Association was negotiating with other East Bay hospitals. Spokeswoman Edna Behrens told the Tribune their contracts called for a 44-hour work week beginning July 1 and a 40-hour week as of January 1, 1947. She said the shortened week would not mean a reduction in the minimum salary of $200 per month.

While nurses felt empowered after the war to pursue higher positions in the field of medical care, not everyone was anxious to embrace them in new roles. A case in point is neurosurgeon Howard Naffziger, who spoke in 1947 at a two-day conference of the Association of California Hospitals at Hotel Claremont in Oakland. “Highly specialized nurses should be called something else, because they have specialized themselves right out of the care of the sick.” He said nurses could learn all they needed to know in 2 years, or even one year of training. “The needs of the public for nurses exceed the ability of the public to pay,” the renowned neurosurgeon said.

Marguerite McLean, then superintendent of nurses at Highland Hospital and later director of the Permanente School of Nursing, countered his remarks: “Doctors …have had to spread themselves so thin that one wonders what would happen if nurses hadn’t been qualified to step in and take care of the situation,” McLean told the Oakland Tribune. She added that even the practical nurse with less training would need a living wage, which would have to be close to the $200 basic monthly pay of the trained nurse. “Nurses feel they are best qualified to know and understand nursing requirements.”