Can the badly broken prescription drug market be fixed?

Prescription drugs are unaffordable for millions of people. With the right policy solutions, we can get back on the path to affordability.

The high cost of prescription drugs is making them unaffordable for patients.

By Anthony A. Barrueta, Senior Vice President, Government Relations

In a free market, sellers compete on price, and buyers choose the lowest priced good that meets their needs. It’s a fundamental law of economics.

But in the real world, this law sometimes crumbles — especially in America’s prescription drug market.

Drugmakers rarely compete on price. This is one reason why the U.S. spent over $633 billion on prescription drugs last year.

Compared with other high-income countries, the U.S. has the highest per capita prescription drug spending.

How government policies led to higher drug prices

Starting in 1990, a series of policy changes undermined any leverage buyers had to help rein in rising costs.

- Medicaid Drug Rebate Program — Congress introduced the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program in 1990. Under this law, in exchange for having all of their drugs covered, drugmakers agree to pay rebates to state Medicaid programs. Because the law requires that Medicaid receive the “best price,” manufacturers cannot offer deeper discounts to private purchasers. This price floor means Americans with private health insurance (that is, most Americans) pay higher prices for drugs and higher premiums for drug coverage than they otherwise could.

- Health plans covering most drug costs — Over time, health plans have paid for a larger share of the total cost of prescription drugs. Even before Medicare started offering prescription drug coverage in 2006, consumers had become more insulated from the full price of drugs. This helped consumers afford their medications. But patients and their doctors are often unaware of the full price of a drug. They have no reason to seek or choose an equally effective, lower-priced alternative.

- Loopholes in patent laws — When the federal government grants a drugmaker a patent, only the company that holds the patent can make and sell the drug for a period of time. Without competition, these drugmakers can set whatever price they like. Patents are important to stimulate innovation. But there are loopholes. In some cases, drugmakers get patents — and great financial rewards — based on publicly financed drug research. Sometimes they build a complex web of patents. Called patent thickets, these webs make it much harder for competitors to come to market.

This combination of policies has allowed manufacturers to raise prices relentlessly without fear of political or market consequences.

Policy solutions

The broken prescription drug market makes health care unaffordable for millions. But we have some policy options, including:

- Addressing anticompetitive behavior. We can build a fairer patent system. New legislation in Congress addresses patent thickets and more.

- Increasing the use of biosimilars. At Kaiser Permanente, we use the biosimilar versions of drugs whenever possible. They’re equally effective and less expensive. For example, we’ve switched most of our members to the newest biosimilar for Humira, a prescription medication for rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory diseases. This saved close to $300 million in 2023 alone.

Humira has a list price of $7,000. By switching members to the biosimilar, we lowered costs for our members and employer groups. Congress should make it easier for doctors to use biosimilars with their patients.

- Focusing on the evidence of a drug’s safety and efficacy. We pay far too much for drugs that don’t improve health outcomes or that show little value over alternative treatments. New policies should strengthen how the Food and Drug Administration approves drugs. This will ensure that available drugs are safe and work well.

- Strengthening Medicare’s ability to negotiate drug prices. Thanks to a law passed in 2022, Medicare can now negotiate the price of a few of the costliest drugs in the US. The drug industry is pushing back aggressively through lawsuits and heavy lobbying. Congress should stand firm and build on this law to protect both Medicare and its beneficiaries into the future.

- Tackling drug shortages. Shortages of specific drugs prevent patients from getting the treatment they need. These shortages also cause rising prices. It’s time our government did more to incentivize companies to make more generic (lower cost) drugs in America. And we need policies that compel drug manufacturers to share more information about their supply pipeline. Then health care systems and providers can identify problems earlier.

The prescription drug market is broken.

It’s time for our lawmakers to have some serious conversations about solutions. Patients deserve access to effective drugs at prices we all can afford.

-

Social Share

- Share Can the Badly Broken Prescription Drug Market Be Fixed? on Pinterest

- Share Can the Badly Broken Prescription Drug Market Be Fixed? on LinkedIn

- Share Can the Badly Broken Prescription Drug Market Be Fixed? on Twitter

- Share Can the Badly Broken Prescription Drug Market Be Fixed? on Facebook

- Print Can the Badly Broken Prescription Drug Market Be Fixed?

- Email Can the Badly Broken Prescription Drug Market Be Fixed?

February 18, 2026

A better approach to preventing chronic conditions

With the right support from our policy leaders, we can help ensure fewer …

January 16, 2026

The importance of childhood vaccinations

Kaiser Permanente continues to recommend the vaccines that have been on …

January 14, 2026

Allegations related to Medicare risk adjustment resolved

The settlement agreement reached with the Department of Justice contains …

December 15, 2025

‘Free’ drug samples aren’t really free

Pharmaceutical marketing hurts patient care and drives up costs. At Kaiser …

December 9, 2025

Buprenorphine saves lives. Why can’t more patients get it?

Policy changes are crucial for better opioid addiction treatment.

December 5, 2025

The importance of hepatitis B vaccination for newborns

Kaiser Permanente will continue to offer the hepatitis B vaccine at birth …

November 19, 2025

Will AI rules leave small hospitals behind?

Policymakers can design regulations that protect patients and work for …

November 5, 2025

Update on mental health program progress

The investments we’ve made over the last several years have resulted in …

November 4, 2025

A best place to work for veterans

As a 2025 top Military Friendly Employer, Kaiser Permanente supports veterans …

October 21, 2025

Health coverage is key to early breast cancer detection

Timely screenings save lives and lower costs, but millions of people miss …

October 15, 2025

Kaiser Permanente shows up strong for the annual plane pull

Championing health equity and teamwork drives Kaiser Permanente’s support …

September 5, 2025

Congress must act to keep health insurance affordable

Enhanced premium tax credits help millions of people afford health insurance. …

August 5, 2025

Pharmaceutical marketing hurts patient care

At Kaiser Permanente, our doctors and pharmacists work together to ensure …

July 22, 2025

Mental health care without borders

When clinicians can practice across state lines, more people can get the …

June 26, 2025

Our commitment to vaccine access

Kaiser Permanente’s statement on vaccine access.

June 17, 2025

We must grow the health care workforce

At Kaiser Permanente, we educate future clinicians and offer programs that …

May 21, 2025

Trust unlocks AI’s potential in health care

Artificial intelligence can improve health care by reducing administrative …

April 21, 2025

Congress must protect Medicaid and insurance tax credits

Medicaid and tax credits for acquiring coverage are essential for patients, …

March 27, 2025

We’re committed to mentorship, mental health, and communities

Kaiser Permanente awarded Elevate Your G.A.M.E. a grant to expand program …

March 25, 2025

AI in health care: 7 principles of responsible use

These guidelines ensure we use artificial intelligence tools that are safe …

March 24, 2025

Our nation's health depends on coverage

Health insurance is key to a strong country — it improves health and boosts …

March 17, 2025

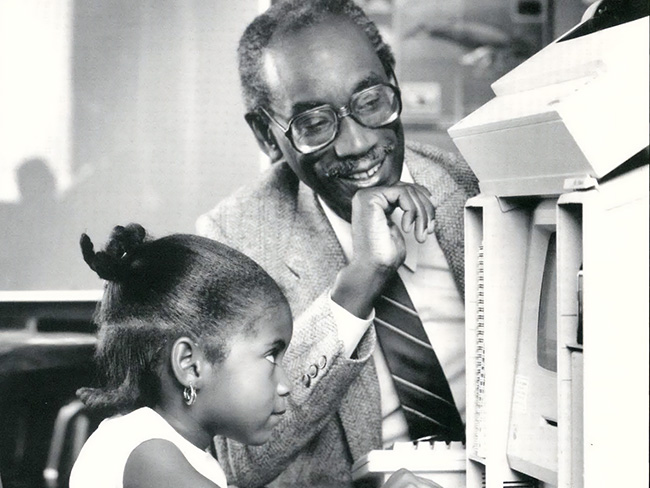

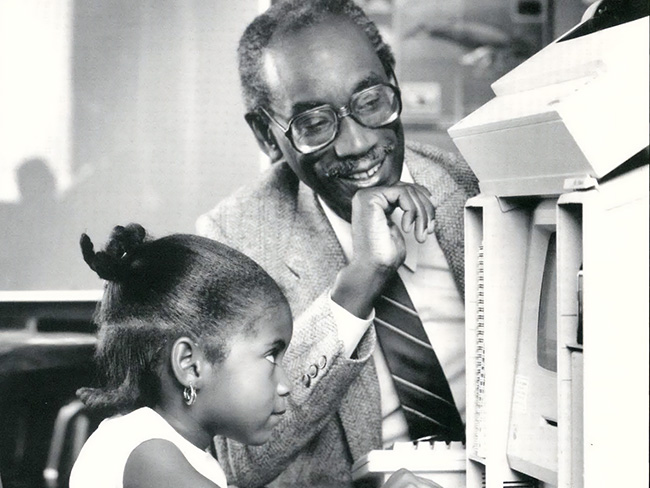

Remembering Bill Coggins and his lasting legacy

The founder of the Kaiser Permanente Watts Counseling and Learning Center …

February 20, 2025

Our nation’s health suffers if Congress cuts Medicaid

Reducing Medicaid funding will lead to worse health outcomes, overburden …

January 15, 2025

Why the U.S. needs more community health workers

With the right strategies and public policies, we can strengthen our nation’s …

January 10, 2025

Kaiser Permanente and UFCW Local 7

Read our statement.

December 26, 2024

Linking isolated communities to care

A collaborative partnership, powered by trusted nonprofit partners, brings …

December 10, 2024

Accelerating growth in the mental health care workforce

Actions policymakers can take to grow and diversify the mental health care …

November 11, 2024

Health care coverage now accessible to uninsured people

Indigenous farmworkers may qualify for new Kaiser Permanente coverage.

November 11, 2024

Medicare telehealth flexibilities should be here to stay

We urge Congress to extend policies that have improved access to care and …

October 15, 2024

Our dedication to fostering well-being and equity

The 2023 Kaiser Permanente Southern California Community Health County …

September 16, 2024

Voting affects the health of our communities

In honor of National Voter Registration Day, we encourage everyone who …

July 22, 2024

Our nation’s health depends on well-funded research

Advanced medical science improves patient outcomes. We urge lawmakers to …

July 16, 2024

Teacher residency program improves retention and diversity

A $1.5 million Kaiser Permanente grant addresses Colorado teacher shortage …

June 19, 2024

Investments in Black community promote total health for all

Funding from Kaiser Permanente in Washington helps to promote mental health, …

April 12, 2024

It’s time to address America’s Black maternal health crisis

Health care leaders and policymakers should each play their part to help …

March 19, 2024

Fostering responsible AI in health care

With the right policies and partnerships, artificial intelligence can lead …

March 18, 2024

Program helps member prioritize her health

Medical Financial Assistance program supports access to health care.

March 6, 2024

Former employee honored for supporting South LA families

Bill Coggins, who founded the Kaiser Permanente Watts Counseling and Learning …

March 4, 2024

Taking care of Special Olympics athletes

Kaiser Permanente physicians and medical students provide medical exams …

February 12, 2024

Proposition 1 would bolster mental health care in California

Kaiser Permanente supports the ballot measure to expand and improve mental …

February 2, 2024

Expanding medical, social, and educational services in Watts

Kaiser Permanente opens medical offices and a new home for the Watts Counseling …

January 31, 2024

Prioritizing policies for health and well-being in Colorado

CityHealth’s 2023 Annual Policy Assessment awards cities for their policies …

January 22, 2024

Solutions for strengthening the mental health care workforce

Better public policies can help address the challenges. We encourage policymakers …

December 20, 2023

Funding solutions to end gun violence

Researchers and organizations are exploring inventive ways to reduce gun …

December 20, 2023

Championing inclusivity at the Fall Games

Kaiser Permanente celebrates inclusion at Special Olympics Southern California …

December 15, 2023

Climate change is already affecting our health

The health care industry is responsible for 8% to 10% of harmful emissions …

December 7, 2023

Safe, secure housing is a must for health

We offer housing-related legal help to prevent evictions and remove barriers …

December 6, 2023

Solid foundation: How construction careers support health

Steady employment can improve a person's health and well-being. Our new …

November 13, 2023

Congress must act to address drug shortages

Kaiser Permanente is working to address drug shortages and support policies …

November 9, 2023

New 4-year agreement ratified

National agreement between Kaiser Permanente and the Coalition will help …

November 1, 2023

Meet our 2023 to 2024 public health fellows

To help develop talented, diverse community leaders, Kaiser Permanente …

October 12, 2023

Our commitment to transforming mental health care in California

Kaiser Permanente and the California Department of Managed Health Care …

September 8, 2023

Regulated waste settlement in California

We are committed to the well-being of the environment and protecting the …

September 6, 2023

Advancing mental health crisis care through public policy

Organizations that provide public mental health crisis services must work …

August 15, 2023

'Hot-spot' strategy gets more Californians vaccinated

A new location-based vaccine strategy by Kaiser Permanente was successful …

August 10, 2023

Highlighting our community health work in Southern California

The Kaiser Permanente Southern California 2022 Community Health Snapshot …

August 2, 2023

Social health resources are just a click or call away

The Kaiser Permanente Community Support Hub can help members find community …

July 26, 2023

Kaiser Permanente hiring 10,000 new staff for Coalition jobs

More than 6,500 of these union-represented positions have already been …

July 11, 2023

Our prescription for safe, effective, more affordable drugs

Our approaches ensure effectiveness and safety, and drive cost savings. …

June 30, 2023

Our response to Supreme Court ruling on LGBTQIA+ protections

Kaiser Permanente addresses the Supreme Court decision on LGBTQIA+ protections …

June 29, 2023

Our response to Supreme Court's ruling on affirmative action

Kaiser Permanente addresses the Supreme Court decision on affirmative action …

June 29, 2023

Special Olympics athletes go for the gold

Kaiser Permanente celebrated its sixth year as official health partner …

June 14, 2023

Honored for commitment to people with disabilities

The Achievable Foundation recognized Kaiser Permanente for its work to …

June 7, 2023

Engaging businesses for action on climate and health equity

New climate collaborative with BSR announced at joint Kaiser Permanente …

June 1, 2023

Policy recommendations from a mental health therapist in training

Changing my career and becoming a therapist revealed ways our country can …

May 22, 2023

Investing and partnering to build healthier communities

Kaiser Permanente supports Asian Americans Advancing Justice to promote …

May 10, 2023

A workplace for all

We are building inclusive work and care environments where everyone feels …

May 10, 2023

Health equity, inclusion, and belonging

We strive for fairness, respect, and inclusion for all.

May 2, 2023

Women lead an industrial revolution at the Kaiser Shipyards

Early women workers at the Kaiser shipyards diversified home front World …

April 27, 2023

Inspiring students to pursue health care careers

Kaiser Permanente is confronting future health care staffing challenges …

April 25, 2023

Hannah Peters, MD, provides essential care to ‘Rosies’

When thousands of women industrial workers, often called “Rosies,” joined …

April 11, 2023

Collaboration is key to keeping people insured

With the COVID-19 public health emergency ending, states, community organizations, …

April 5, 2023

Housing help brings stability to patients’ lives

With medical-legal partnerships, we’re helping prevent evictions. Patients …

April 3, 2023

Hospital patients who are homeless connected to housing

A Kaiser Permanente program connects patients experiencing homelessness …

March 29, 2023

Supporting a safer future with public health

We’re partnering on 3 initiatives to strengthen public health in the United …

February 17, 2023

Good health starts in our communities: 2022 by the numbers

Kaiser Permanente supports total health in our communities in partnership …

January 17, 2023

Lawmakers must act to boost telehealth and digital equity

Making key pandemic-era telehealth policies permanent and ensuring more …

December 5, 2022

Want to lower drug prices? Reform the U.S. patent system

Pharmaceutical manufacturers that exploit the current system drive up …

November 14, 2022

It’s time to rethink health care quality measurement

To meaningfully improve health equity, we must shift our focus to outcomes …

November 11, 2022

High-quality, equitable care

We believe everyone has a right to good health.

November 11, 2022

Early leaders in equity and inclusion

Explore Kaiser Permanente’s commitment to equitable, culturally responsive …

November 8, 2022

Protecting access to medical care for legal immigrants

A statement of support from Kaiser Permanente chair and CEO Greg A. Adams …

October 21, 2022

Kaiser Permanente therapists ratify new contract

New 4-year agreement with NUHW will enable greater collaboration aimed …

August 16, 2022

Our support for the Inflation Reduction Act

A statement from chair and chief executive Greg A. Adams on the importance …

May 2, 2022

How to transform mental health care: Follow the research

We applaud President Biden and Congress as they begin to set policies that …

March 22, 2022

NUHW psych-social employees ratify agreement

The agreement between Kaiser Permanente and the NUHW in Southern California …

March 22, 2022

Our commitment to equity and our LGBTQIA+ communities

A statement from chair and chief executive officer Greg A. Adams.

February 21, 2022

A best place to work for LGBTQ+ equality

Human Rights Campaign Foundation gives Kaiser Permanente another perfect …

February 14, 2022

Health care scholarships available

Kaiser Permanente in Hawaii to provide up to $100,000 in scholarships to …

October 12, 2021

Beyond advocacy: Requiring vaccination to stop COVID-19

Kaiser Permanente and other leading companies are mandating COVID-19 shots …

August 25, 2021

Kaiser Permanente’s history of nondiscrimination

Our principles of diversity and our inclusive care began during World War …

July 7, 2021

Achieving health equity

Equal medical care is not enough to end disparities in health outcomes.

June 2, 2021

Path to employment: Black workers in Kaiser shipyards

Kaiser Permanente, Henry J. Kaiser’s sole remaining institutional legacy, …

April 27, 2021

Health data privacy

Protecting our members’ personal health information

April 23, 2021

Medicaid

Delivering high-quality Medicaid coverage and services

April 27, 2020

Health care reform

Affordable, accessible health care and coverage

March 4, 2020

Our impact

How Kaiser Permanente strengthens communities and advances public policies …

March 1, 2020

Prescription drug pricing

Bringing down the high cost of medication

February 29, 2020

California