Marking half a century of stellar research

Kaiser Permanente's Division of Research has conducted pioneering health and medical research using emerging technology since 1961.

Ellsworth Dougherty, MD, one of Kaiser Permanente's earliest researchers, studied the worm that eventually led to the mapping of the human genome. This photo is from a research trip he took to Antarctica circa 1959.

Kaiser Permanente has a well-deserved public reputation for providing top-quality health care, but less known is the health plan's long and illustrious record for conducting high-caliber medical research. Kaiser Permanente is widely considered the leading non-university-based health research organization in the United States, with Kaiser Permanente Northern California’s Division of Research amassing more than $100 million in 2011 to conduct research.

This research has a direct effect on health care in this country, influencing the way physicians care for patients and refining broader policies that support medical services. Kaiser Permanente researchers, often partnering with academic institutions, successfully compete for federal research grants, and develop lines of research whose results translate to improved patient outcomes at the local, state, and national levels.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Research Director Jeffrey Harris, MD, put it this way: “If you look at who the leaders in research are and who the folks are that have been doing research … to improve care, it’s a very short list. And Kaiser Permanente is clearly at the top of that list.”1

This year, The Permanente Medical Group, the oldest of the eight Kaiser Permanente regional medical groups, celebrates the 50th anniversary of the founding of its Division of Research.

In the past 5 decades, Kaiser Permanente researchers have conducted thousands of studies and helped to solve many medical mysteries — from the best way to cure pneumonia in the World War II shipyards, to making discoveries leading to the mapping of the human genome, to learning the most effective use of drugs to prevent heart attacks.

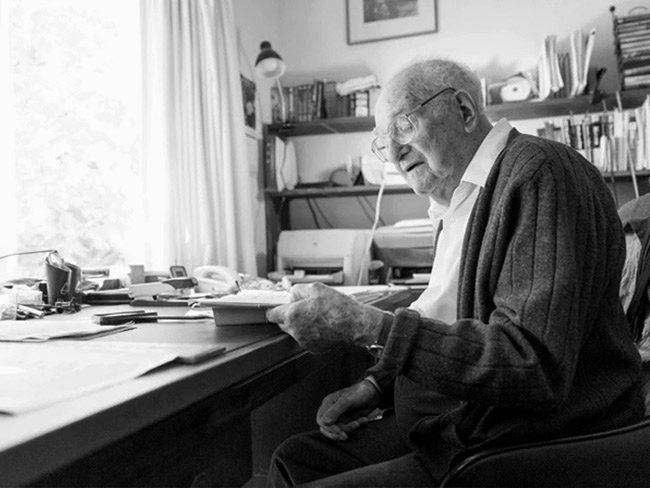

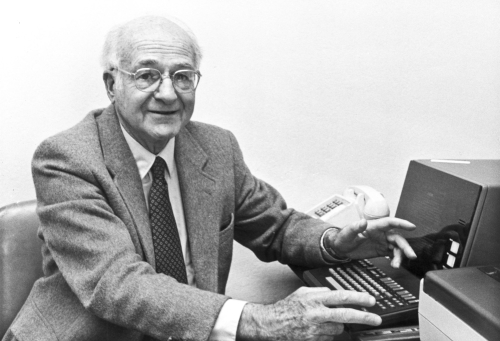

Gary Friedman, MD, led the Division of Research from 1991 to 1998. This image originally appeared in the KP Reporter, 1987.

The DOR (under its original name, Medical Methods Research, or MMR) was established on September 21, 1961, by the Northern California medical group’s Executive Committee. Morris F. Collen, MD, one of the Health Plan’s founding members and a pioneer in the emerging discipline of medical informatics, led the group, which occupied offices in the old Kaiser Permanente headquarters at 1924 Broadway in Oakland.

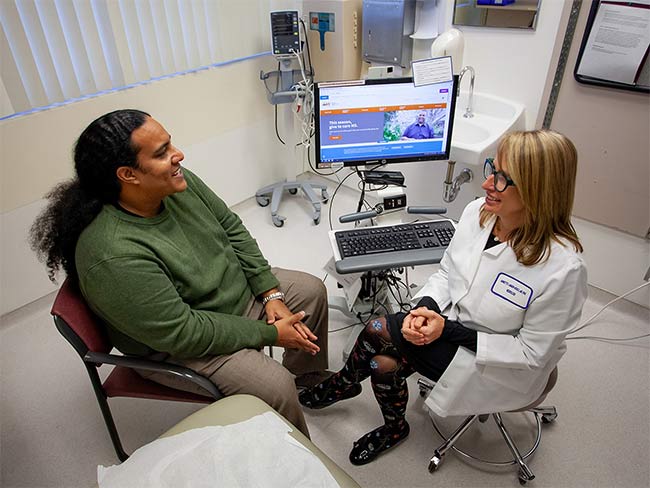

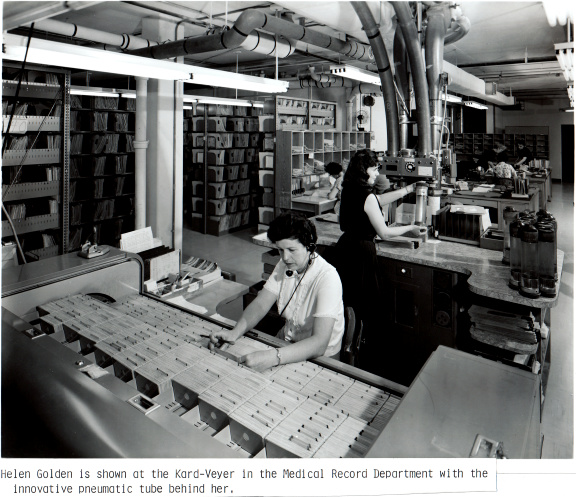

Ten years earlier, Dr. Collen had met with Lester Breslow, MD, then a public health officer in San Jose who had recently completed a trial of “multiphasic screening.” This battery of thorough and efficient examinations was a practical solution to the problem of providing care to large populations despite the post-war shortage of physicians.

This approach was put to the test when labor leader Harry Bridges insisted that all members of the International Longshore and Warehousemens Union be given annual check-up exams as part of a negotiated care package with the Permanente Health Plan. Importantly, this exam approach provided a critical evidence base to empirically determine what screening methods are and are not clinically beneficial for patients.

In 1962, Kaiser Permanente Northern California received its first grant from the U.S. Public Health Service to develop, automate, and evaluate the multiphasic exam. Within 3 years, the Health Plan’s Oakland and San Francisco clinics began offering the Automated Multiphasic Health Testing to all members. In 1968 Dr. Collen dismissed some of the resistance to this use of technology:

"Many physicians are concerned that the computer is depersonalizing medical care," he said. "Just the opposite is true. Because of the computer, the physician will have more individualized information about his patient—more complete and more accurate than he could possibly have gathered before.”2

Antecedents to Permanente medical research

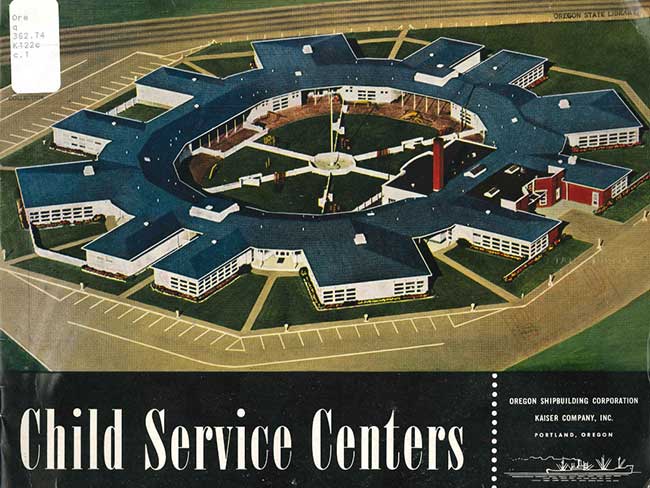

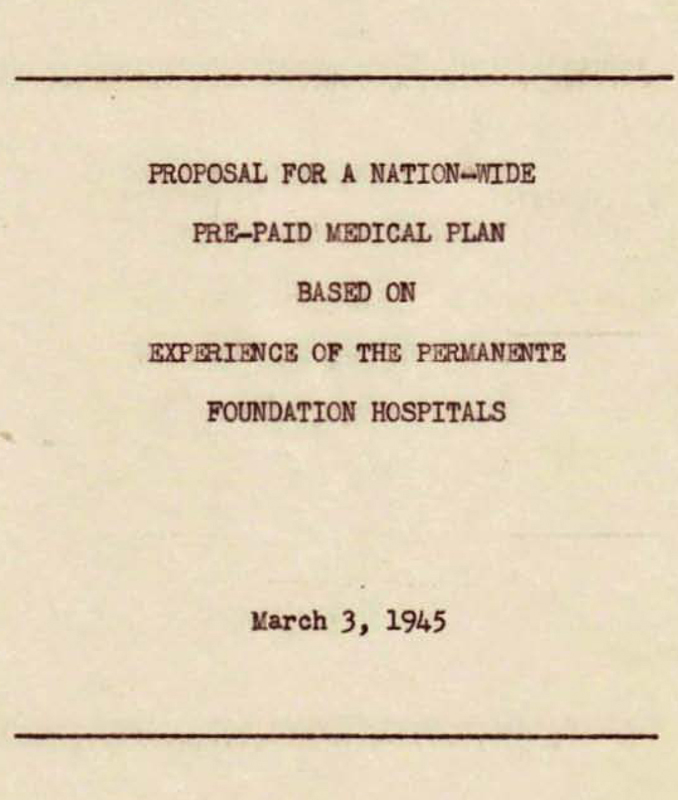

Even before the Health Plan went public in 1945, Henry J. Kaiser articulated research as one of its goals at the August 21, 1942, dedication of the Permanente Foundation Hospital in Oakland. As former Kaiser Permanente historian Tom Debley observed:

“From prepaid dues, it collected, the Permanente Foundation paid for the medical care of Health Plan members and accumulated funds for such charitable purposes as medical research and the extension of medical services to a larger population ... The idea that research would be a tool to bring advances in medicine to the plan’s dues-paying members thus was embedded in the medical care program from the outset.”3

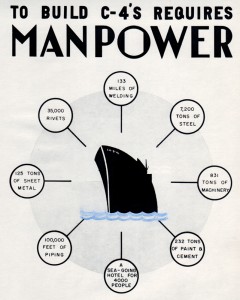

In 1943, founding physician Sidney R. Garfield received $25,000 from the Permanente Foundation to study new methods of curing syphilis4 and he launched the Permanente Foundation Department of Medical Research under the leadership of Franz R. Goetzl, PhD, MD. He also started the research journal Permanente Foundation Medical Bulletin, edited by Dr. Collen from 1943–1953.

The Department began to receive national recognition for outstanding work in the study of peptic ulcers, human appetite, and pain. By 1949 the name was changed to The Permanente Foundation Institute of Medical Research to clarify that the research was not only a department within the hospital.

Ernest Saward, MD, medical director of Kaiser Permanente Northwest from 1945 to 1970, launched the region’s research center in 1964.

In late 1958, research involving basic medical sciences was shifted to the Kaiser Foundation Research Institute, or KFRI, established by Kaiser Foundation Hospitals to coordinate long-term basic research projects supported by grants from sources other than the Kaiser Foundation Medical Care Program.5 At first this just covered Northern California’s MMR and the Northwest Research Center (established in 1964.)

Today, all Kaiser Permanente regions — Hawaii, Georgia, Ohio, Colorado, Northwest, Northern and Southern California, and the Mid-Atlantic States, conduct research under the auspices of the KFRI.

By 1961 KFRI’s domain included more than 50 long-range clinical research studies exploring such medical problems as cardiovascular and renal diseases, adenovirus infections, cancer, diabetes mellitus, and psychosomatic medicine. More than 70 staff physicians and residents conducted these investigations, often in collaboration with laboratories at nearby medical and scientific institutions.

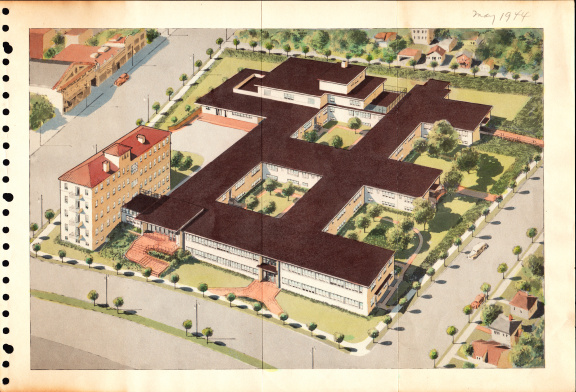

Clifford H. Keene, MD, chief executive officer of Kaiser Foundation Hospitals and Health Plan, was named director of KFRI.6 A wing of Kaiser Foundation Hospital in Richmond was remodeled to bring together several disparate research projects under the KFRI umbrella.

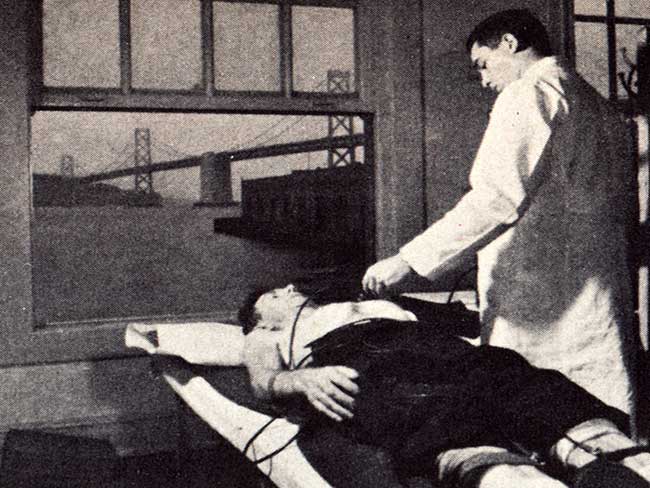

These included a laboratory of comparative biology (under Ellsworth C. Dougherty, PhD, MD) studying the basic physiology of microorganisms; a laboratory of medical entomology (under Ben F. Feingold, MD) investigating the role of insects in causing human allergies; a laboratory of human functions; a study of the epidemiology of human cancer; and a child development study and blood grouping project that investigated congenital abnormalities and childhood diseases.

Kaiser Permanente Northern California research evolves

During the late 1960s Edmund Van Brunt, MD, a project director for MMR, piloted the San Francisco Medical Data System, a computer-based patient medical record system with a database that supported both patient care and health care delivery research. By 1973, Health Plan members in San Francisco had a computerized “lifetime” medical record, and pivotal work was conducted to begin to understand the safety of prescription drugs.

But by the early 1970s researchers were forced into a different avenue of research when the Nixon Administration abruptly canceled the department’s funding. The loss of $500,000 per year led to a shutdown of the hospital computer system in San Francisco, but the application of computers and databases in medicine and health research continued, supporting new investigators and new areas of research. In 1979 Dr. Van Brunt succeeded Dr. Collen as the second director of the research department, and in 1986 he changed the name to the current Division of Research, or DOR, to more accurately reflect the expanded mission and scope of clinical and other types of research that were being conducted there. Recently he described his vision of the program:

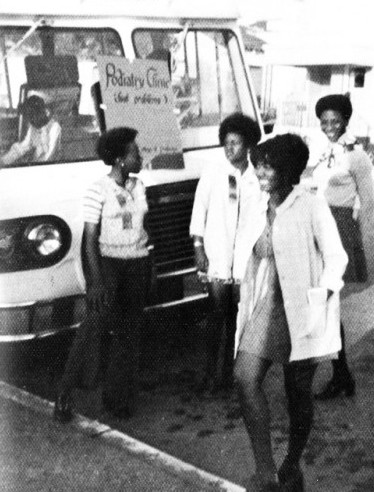

Mary Belle Allen, PhD, conducted her studies in the Richmond KP laboratory along with Ellsworth Dougherty, MD. This photo is from the KP Reporter, 1959.

“[We] conducted high-quality health services and biomedical research, epidemiologic and vital statistical analysis of the whole variety of medical care processes ... of different collections of people drawn ... from the Health Plan membership and by different collections of people ... males, females, different ethnic groups, young and old.”

Van Brunt continued: “ ... The mission is to use these resources to conduct the kinds of health services research that we feel are important not just to the organization but important in a larger sense.”7 Dr. Van Brunt expanded DOR’s research agenda by adding a department of Technology Assessment headed by Director Emeritus Collen.

In 1985 Kaiser Permanente Northern California opened its first research clinic to support the heart disease research study CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults). Within a year it was looking at a group of 5,115 Black and white men and women aged 18-30 years in 4 centers: Birmingham, Chicago, Minneapolis, and Oakland. Also in 1985, MMR began the Vaccine Study Center as a way of responding to numerous requests to use Kaiser Permanente’s large population for vaccine efficacy studies.

The center currently operates 31 sites in Northern California and collaborates with Kaiser Permanente's Northwest, Hawaii, and Colorado regions and participates in several Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Institutes of Health studies.

Studies to better understand HIV/AIDS impact

During the AIDS crisis in the 1980s, DOR proved its worth in analyzing the impact of the disease. Kaiser Permanente Northern California was second only to San Francisco County’s public health services in the number of people with AIDS it treated in the initial years of the crisis.

Consequently, Kaiser Permanente researchers knew how many patients were actively seeking treatment, but they didn’t know how many of its members were infected yet untreated. Anonymous analysis of blood samples taken during routine checkups of 10,000 Kaiser Permanente patients in late 1989 told DOR researchers that 1 in 500 of its members was infected with HIV/AIDS.8

Gary Friedman, MD, succeeded Dr. Van Brunt as director in 1991. During Dr. Friedman's seven-year tenure, the DOR conducted important research on the etiology, prevention and early detection of cancers; on prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease and diabetes; on the determinants of health care utilization; and on population approaches to chronic diseases.

Early research on the effects of socioeconomic status, race, and ethnicity on health care and outcomes laid the foundation for the DOR's ongoing involvement in health disparities research.

In 1994, Kaiser Permanente Northern California became a founding member of the Health Maintenance Organization Research Network (HMORN), ushering in an era of large-scale collaborations seeking to integrate research and practice for the improvement of health and health care in diverse populations.

Long chain of clinician-researcher leaders

Joe Selby, MD, MPH, took the helm in 1998, and former research investigator Tracy Lieu, MD, MPH, was appointed director in 2012, continuing DOR’s unbroken line of leadership by clinician-researchers.

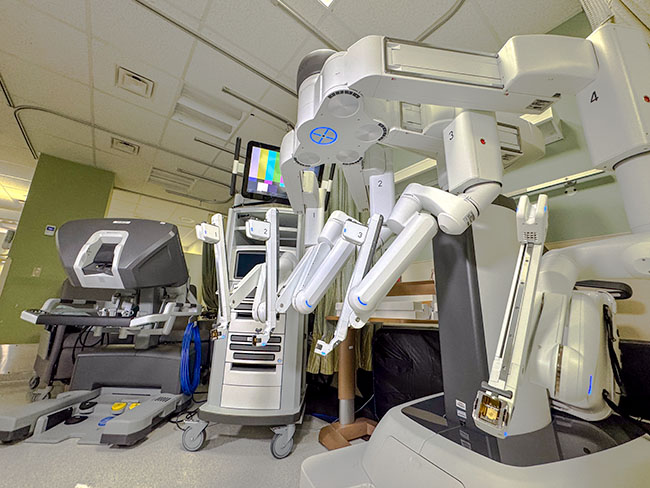

Currently, 58 researchers and over 500 research staff continue DOR’s work in health care delivery research, outcomes research, clinical trials, epidemiology, genetics/pharmacogenetics (how individuals react to drugs), effectiveness and safety research, sociology, qualitative research (conducting patient interviews to better understand study data), and quality measurement and improvement.

Kaiser Permanente’s massive member database and consistent medical record keeping, maintain medical informatics as the cornerstone of Kaiser Permanente research in fields such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, metabolic disorders, dementia, autism, infectious diseases, osteoporosis, maternal and child health, chemical dependency and mental health. Dr. Friedman, Division of Research scientist emeritus, touts Kaiser Permanente data as offering “the best epidemiologic workshop in the world.”

Kaiser Permanente Northern California research also leads or co-leads several national research collaboratives sponsored with federal funds involving multiple Kaiser Permanente and non-Kaiser Permanente organizations, including the Cardiovascular Research Network, Cancer Research Network, Vaccine Study Datalink, Developing Evidence to Inform Decisions about Effectiveness, Accelerating Change and Transformation in Organizations and Networks II, among others.

Overall, DOR has a remarkable history filled with contributions to the health of Kaiser Permanente members and the broader community. DOR is committed to expanding its impact through better understanding of the underpinnings of risk factors and diseases, determining methods for effectively preventing and detecting these conditions, delineating the natural history of diseases, identifying ways to improve outcomes and the overall delivery and organization of health care.

Thanks to Alan Go, MD; Maureen McInaney; and Marlene Rozofsky Rogers at DOR for their contributions in the preparation of this article.

For an introduction to DOR research scientists and their work, please visit divisionofresearch.kaiserpermanente.org. For more information, including all of the published work of DOR authors, please visit The Morris F. Collen, MD Research Library, 2000 Broadway, Oakland, CA. Also see “Something in the Genes: Kaiser Permanente's Continuing Commitment to Research,” by Robert Aquinas McNally, Permanente Journal, Fall 2001

1 “Perspectives – Research,” [videotape] [Oakland (CA):] Kaiser Permanente MultiMedia Communications; 1998, quoted in “Research in Kaiser Permanente: A Historical Commitment and A Future Imperative,” Robert Pearl, MD, Permanente Journal, Fall 2001.

2 Kaiser Foundation Medical Care Program Annual Report 1968.

3 The Story of Dr. Sidney R. Garfield: The Visionary Who Turned Sick Care into Health Care, by Tom Debley, The Permanente Press, 2009.

4 Correspondence November 1, 1943 from E. E. Trefethen, Jr., Trustee of the Permanente Foundation, to Dr. Garfield; letter is an appendix to the Cecil C. Cutting Regional Oral History Office interview 1985 by Malca Chall.

5 Kaiser Foundation Medical Care Program Annual Report 1961.

6 KP Reporter, September 1959.

7 Interview June 13, 2012 by Bryan Nadeau, Senior Producer Northern California Multimedia.

8 “AIDS research among Kaiser’s quiet studies,”Carolyn Newbergh, Oakland Tribune, 10/8/1991. The published medical research finding is: Hiatt RA, Capell FJ, Ascher MS.; Seroprevalence of HIV-type 1 in a northern California health plan population: an unlinked survey.; Am J Public Health. 1992 Apr;82(4):564-7.; PubMed PMID: 1546773; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC1694106.