Henry Kaiser among highway safety pioneers

Kaiser-Frazer automobiles pioneered and embraced safety engineering designs for affordable cars after World War II.

The year is 1946 and Americans are relishing life without war, jumping into a society that offers anyone with a little money the opportunity to drive a car. But trouble erupts almost immediately in the postwar paradise. Primitive roads, unsafe vehicles and unqualified drivers spell an explosion in traffic deaths on American highways — 33,500 people were killed in the year following war’s end.

President Harry Truman was having none of it. He convened a Highway Safety Conference in May of 1946, gathering together in Washington 2,000 officials whose jobs involved transportation and traffic safety. In his opening speech, Truman decried the slaughter on the highways and called for the enactment of laws dictating the qualifications of drivers.

Setting aside his prepared speech, Truman launched into the “most vehement and vitriolic attack on reckless driving ever delivered by a high government official,” said “Public Safety” magazine. “Even the trim MPs stationed at each side of the speaker’s platform were startled out of their impassive rigidity.

“Truman criticized state driver’s license requirements, including those in his home state of Missouri: ‘You know, in some states — my own in particular — you can buy a license to drive a car for 25 cents at the corner drug store. It’s a revenue-raising measure. It isn’t used for safety at all. . . . It’s perfectly absurd that a man or a woman or a child can go to a place and buy an automobile and get behind the wheel — whether he has ever been there before makes no difference, or if he is insane, or he is a nut or a moron doesn’t make a particle of difference — all he has to do is just pay the price and get behind the wheel and go out on the street and kill somebody,’” Truman said.

Big plans to cut traffic deaths

The safety conference adjourned after three days with a consensus on its Action Program to combat highway deaths. Stricter driver’s licensing requirements, education in the schools and an aggressive public information campaign were all part of the ambitious plan they urged state, city, and county officials to adopt.

Truman convened similar conferences in 1947, 1949, 1951, and 1952, and each time participants analyzed the statistics and retooled the Action Program for greater success. But as time went on, overall highway traffic volume shot up, and the fatality total continued to climb. Stats showed 35,000 highway deaths in 1950; 37,500 in 1951; and officials projected 40,000 in 1952.

Traffic safety evangelists, disappointed by the lack of success, adopted a strategy they hoped would bump their public education program forward. Judge Alfred P. Murrah of Oklahoma, chairman of the National Committee for Traffic Safety, expressed it this way: “We come to the realization that it is not enough merely to appeal to the mind; we must appeal to the heart and soul of man. When we have done that, we will build an organization for safety rooted in the hearts and minds of individuals everywhere. That, my friends, is our goal and there can be no turning back.”

Colorado Governor Dan Thornton urged involving industry and business in the traffic safety crusade: “In other emergencies and catastrophes, such as floods or disease . . . the states (have traditionally) enlisted the support of business and industry to help in a crisis. A similar approach could reduce the unnecessary loss of life due to traffic accidents.”

Despite all the government’s heroic highway safety efforts, traffic deaths steadily increased throughout the 1950s and 1960s reaching a high of 55,600 in 1972. As is still true today, teen drivers were responsible for a disproportionate number of highway fatalities during this time.

Kaiser-Frazer embraces safety crusade

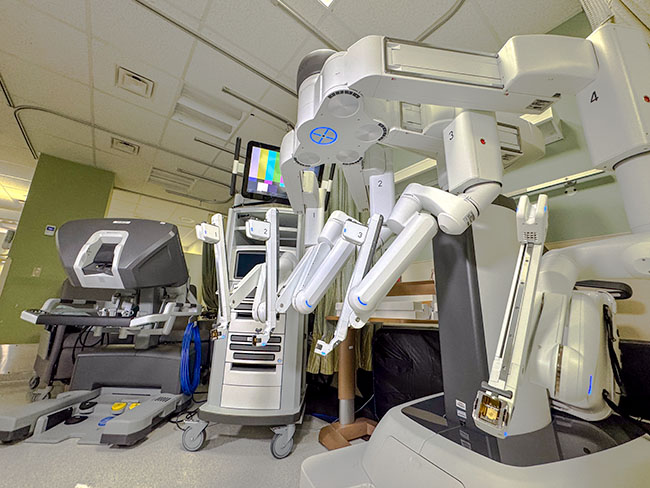

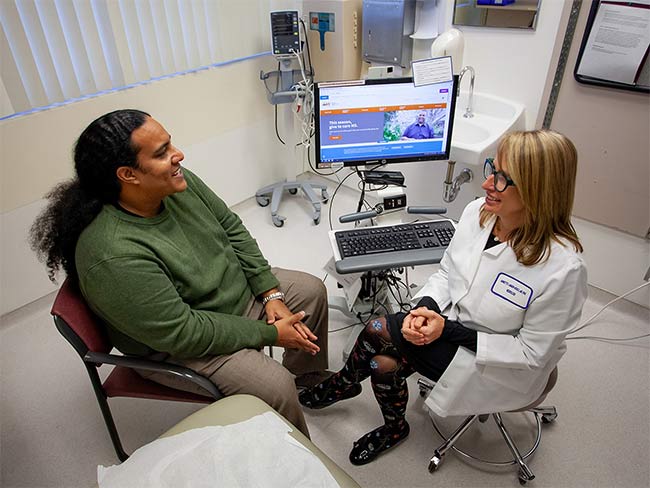

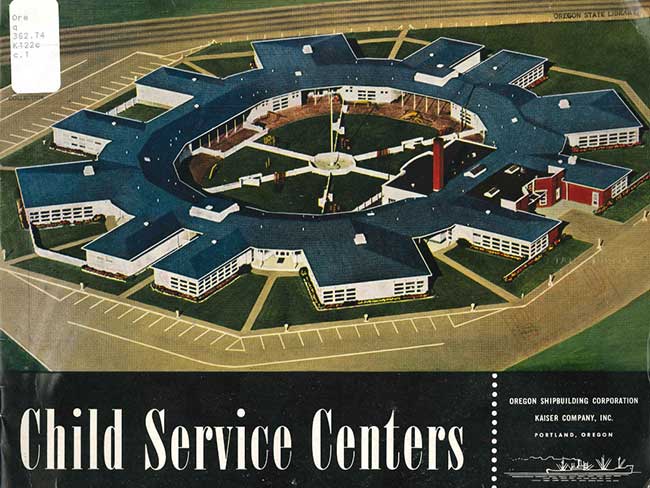

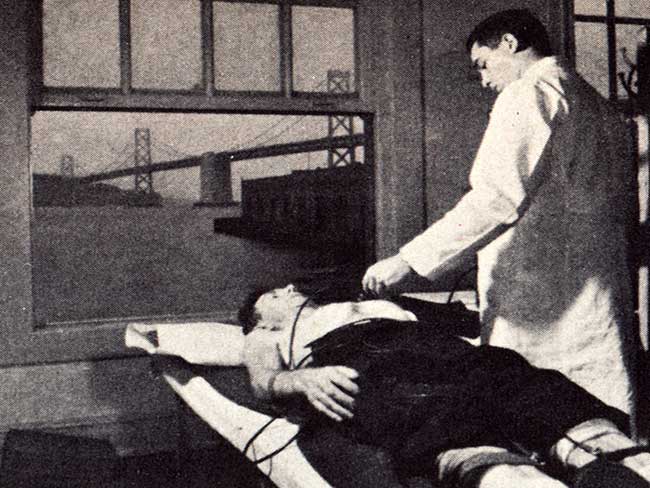

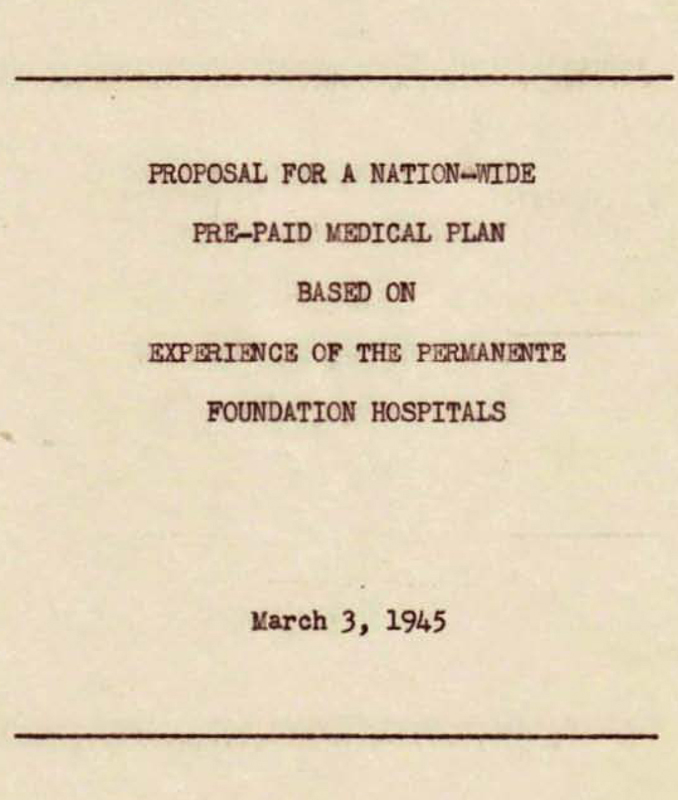

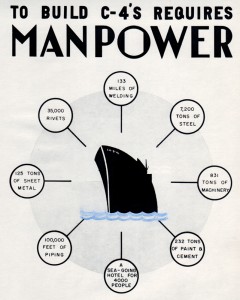

Automobile manufacturers such as Kaiser-Frazer, started by Henry Kaiser and Joe Frazer right after the war, took the safety sermon seriously. They began to do two things: build a safer car and educate drivers, especially newly licensed teenagers, about safe driving. When Kaiser-Frazer came out with its 1953 Kaiser Manhattan, they dubbed it the “World’s First Safety-First Car!” The Manhattan had an extra large windshield for better visibility, a low center of gravity, steering designed for better control as well as a powerful engine, brakes with “more stopping power” and special lighting for better visibility at night.

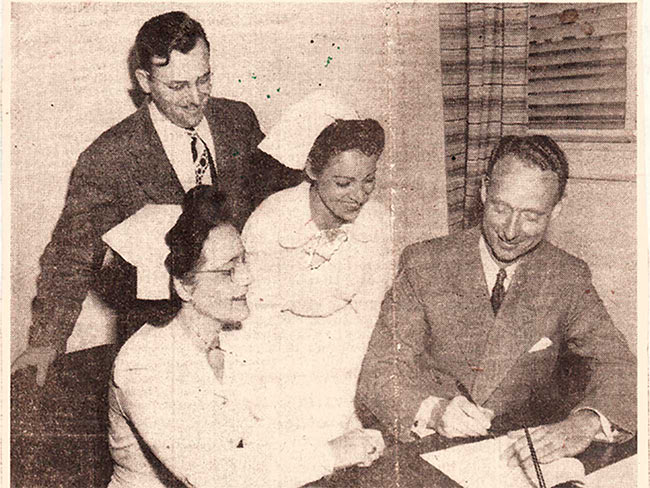

Even before launching its safety-first vehicles in the early 1950s, Kaiser-Frazer began in 1949 to coach its customers on how to teach their teenagers to approach the road with caution and responsibility. The dealership offered boilerplate agreements for fathers and teenagers to sign, setting up rules for safe driving. The “Dad-to-Daughter” and “Man-to-Man” agreements, approved by the National Traffic Safety Committee, included pledges such as these:

“I fully realize the car is not a plaything but a machine that has the power to kill, and I will not try to show off with it;

“I will not race with other cars regardless of how much of a temptation it might be to do so;

“I am fully aware of the risks involved in driving after drinking, and I will not allow the car to be driven by anyone who has been drinking any form of intoxicating liquor while the car is in my charge;

“I hereby give my father my Word of Honor that I will do what I have promised above in consideration of his permission to drive the family car. . . I have signed this agreement of my own free will.”

Curiously, the dad-to-daughter and man-to-man (father-to-son) agreements, although distinctly titled, were identical, making no provision for the inherent differences between teenage girls and boys. Mom was absent from the 1949 equation altogether.

Agreements underline changes in driving attitudes

A comparison of the 1949 and a 2011 parent-teen safe driving agreement reveals the differences – and similarities – of the harrowing experience of getting teens through the early driving challenge. The American Automobile Association’s (AAA) template addresses the same issues as the Kaiser-Frazer agreement: obeying traffic laws and eschewing daring practices such as racing, stunts, and drinking alcohol. It also brings up topics hardly imagined in 1949: “I will not allow drugs or weapons in the car. . . I will pull over and park before using my cell phone, pager or any other electronic devices.” (The Department of Transportation launched “distraction.gov” in 2009 to attack the problem of multi-tasking while driving.)

Another contrasting feature of the AAA agreement versus the Kaiser-Frazer document is the promise to “wear my safety belt at all times,” a sign of the vast updating over five decades of the nation’s laws governing highway safety and the manufacture of safer cars.

The National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act and Highway Safety Act passed in 1966 gave the federal government the authority to set uniform safety standards. These measures, including seat belt requirements, finally began to reverse the upward trend by the early 1970s.

In April of this year, the government reported the rate of fatalities in 2010 fell to the lowest levels since 1949 despite a significant increase in the number of miles driven. In announcing the 2010 numbers, Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood said: “Still, too many of our friends and neighbors are killed in preventable roadway tragedies every day. We will continue doing everything possible to make cars safer, increase seat belt use, put a stop to drunk driving and distracted driving and encourage drivers to put safety first.”