Transforming the medical record

Kaiser Permanente’s adoption of disruptive technology in the 1970s sparked a health care revolution in diagnostics and recording.

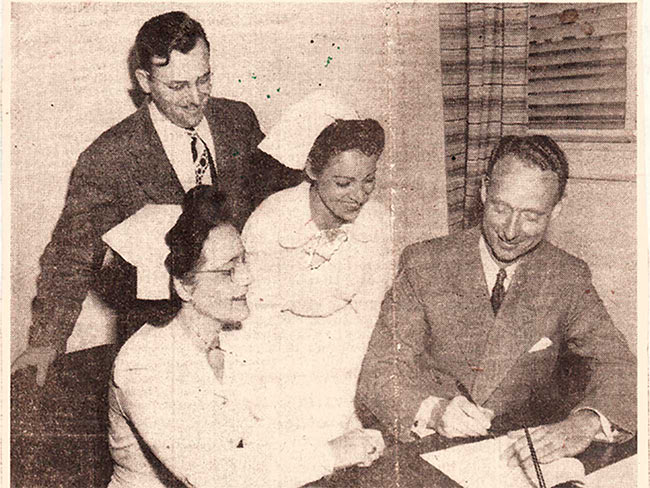

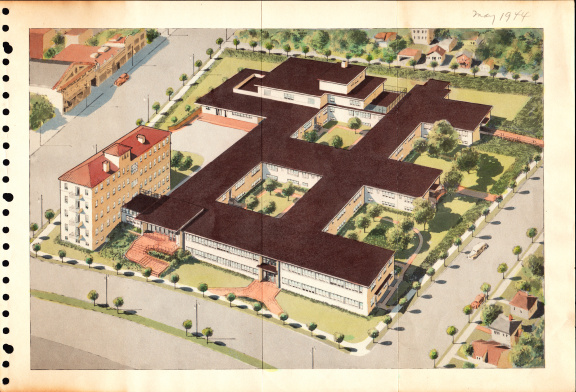

The automated multiphasic health test was supported by the IBM System 360 in the Kaiser Permanente Oakland Hospital computer center in 1966.

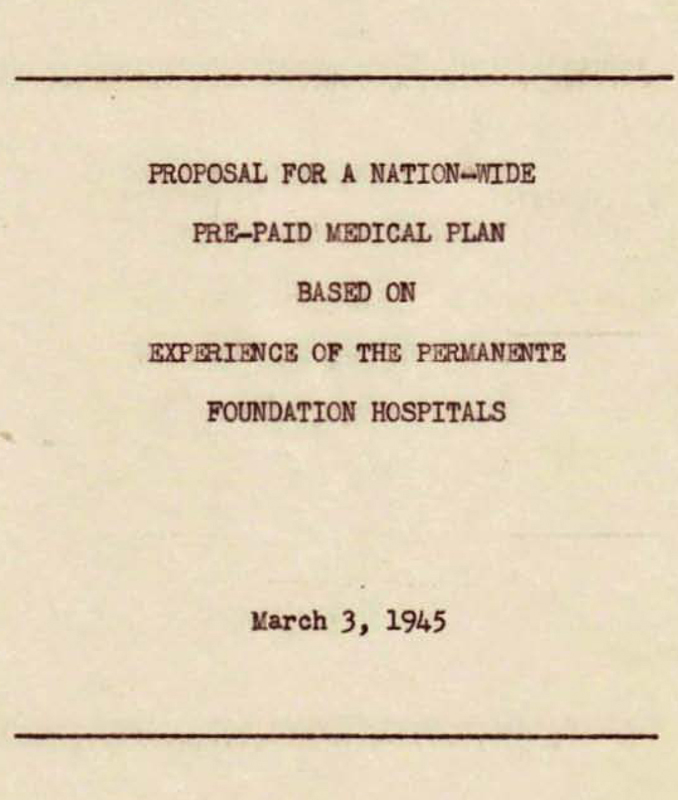

In the early 1950s, Kaiser Permanente led a pioneering approach to preventive medicine. The concept was simple. Detect illnesses early with annual health tests to prevent serious illnesses.

The multiphasic health test became essential in building our integrated care model. Computer technology later led to new health research and clinical practices that continue today.

Computers shift the health care model

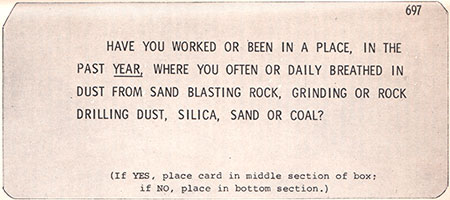

Patients were asked to sort prepunched questionnaire computer cards to describe their medical history.

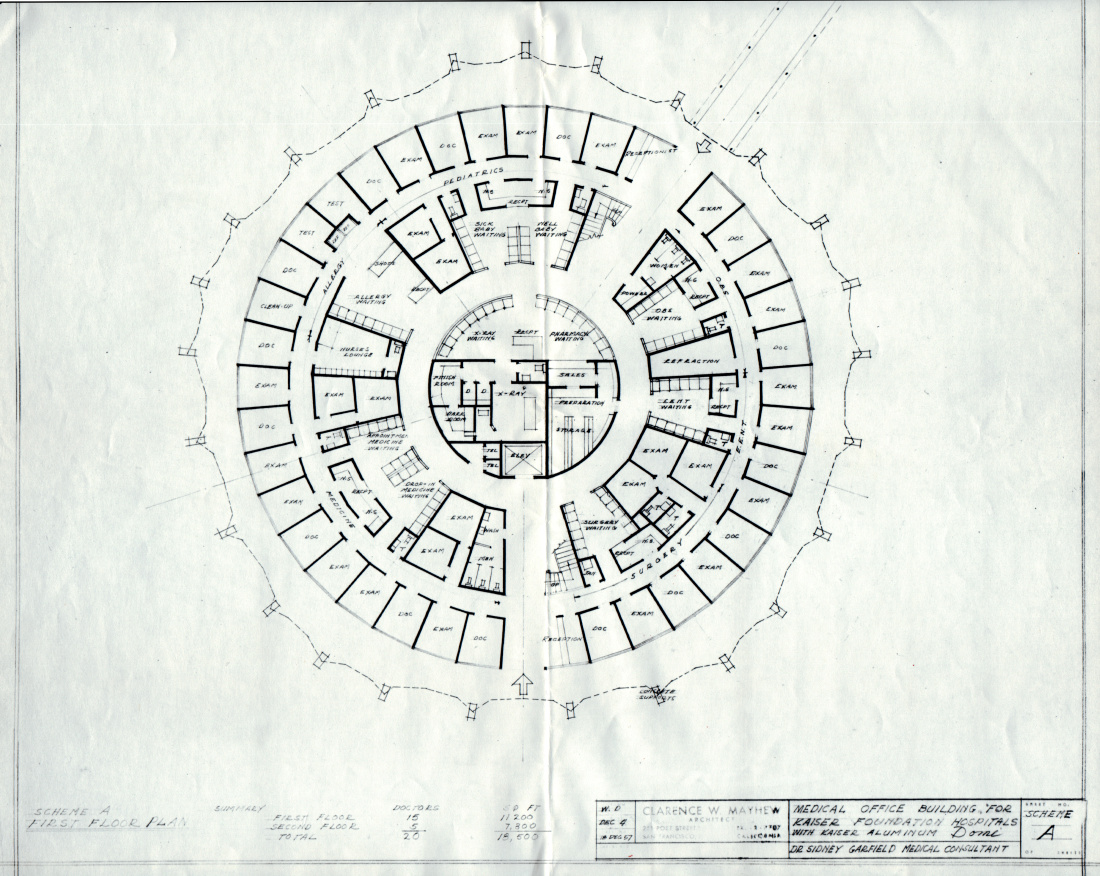

The Kaiser Foundation Research Institute received a grant in 1961 from the U.S. Public Health Service to adopt and use computer processors. The goal was to automate the decade-old multiphasic health test, conducted manually by Kaiser Permanente doctors and nurses.

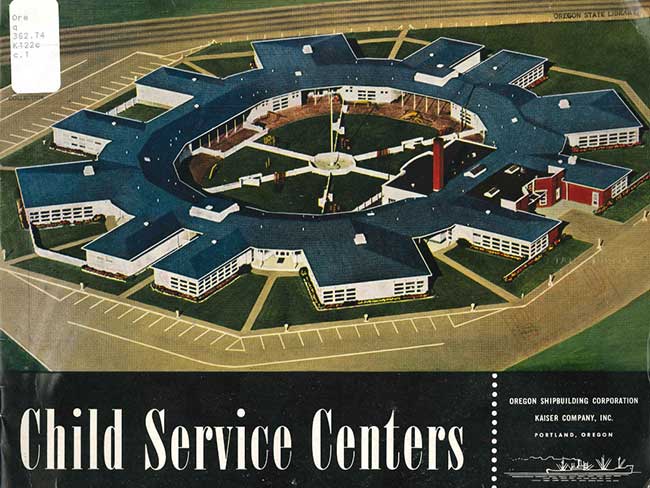

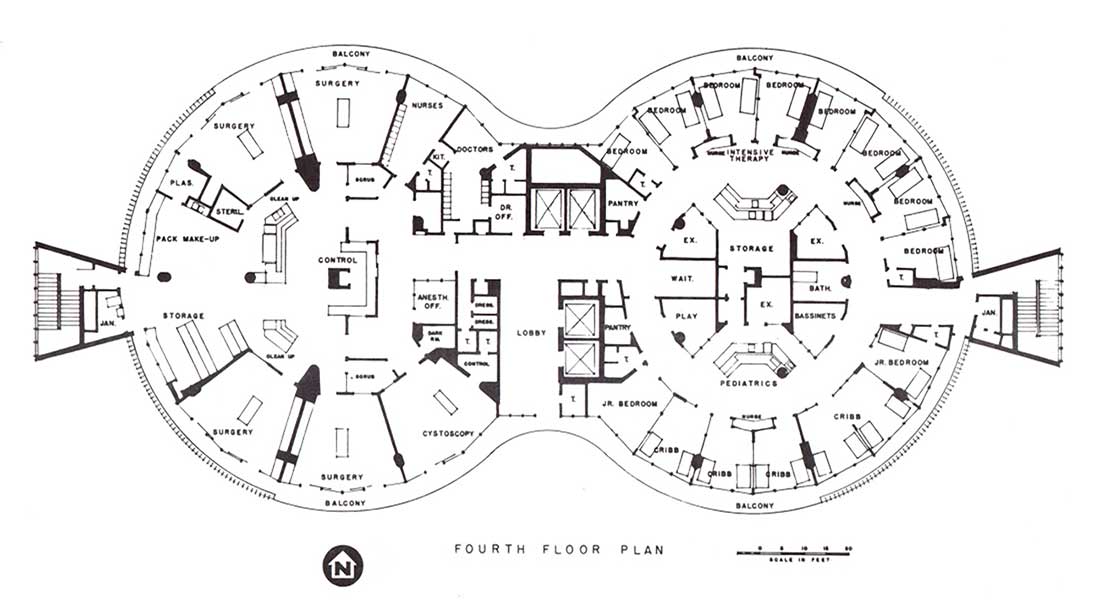

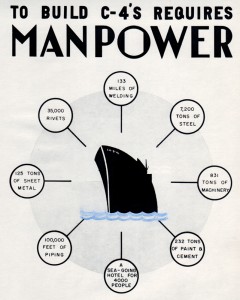

The new automated multiphasic health test (AMHT) center opened at Kaiser Permanente’s Oakland Hospital in 1962. After checking in, members used computer punch cards to answer questions. Staff processed the punched cards at the end of a patient's visit by placing them into an IBM sorter. The machine sorted the patient's results into 'normal' and 'abnormal' for follow-up visits. The automated health test reduced the annual health exam to a couple of hours and gave members a printed summary of their medical records and current health status.

HAVE YOU WORKED OR BEEN IN A PLACE, IN THE PAST YEAR, WHERE YOUR OFTEN OR DAILY BREATHED IN DUST SAND BLASTING ROCK, GRINDING OR ROCK DRILLING DUST, SILICA, SAND OR COAL? (If YES, place card in the middle section of box: if NO, place in the bottom section.)

By the end of 1966, the Oakland building that housed the AMHT center was expanded with updated testing facilities, laboratories, a computer center, and offices. A second AMHT center opened at the Kaiser Permanente San Francisco Medical Center with a connection to the mainframe computer in Oakland.

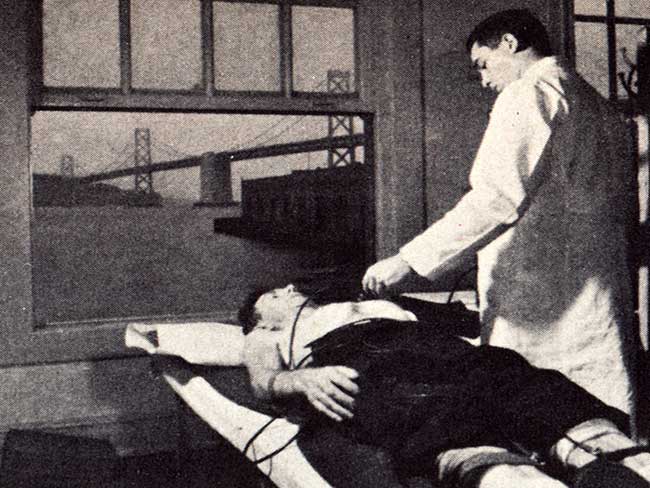

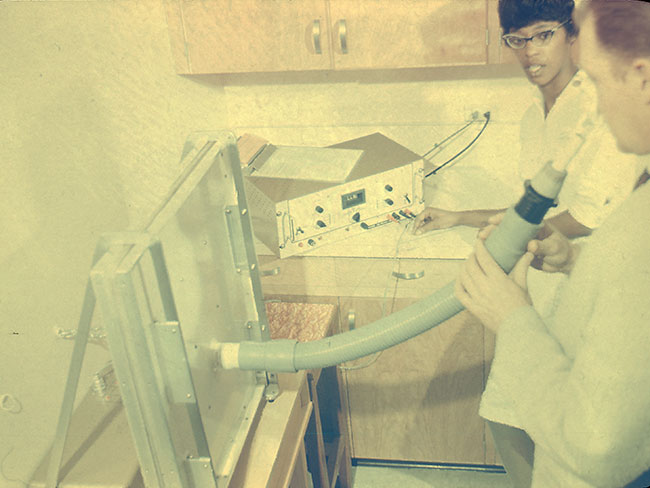

The comprehensive health test required patients to measure their lung capacity at phase 12 by blowing air into a device.

The multi-station process of the automated multiphasic health test included X-ray images taken of the chest at phase 5.

The advent of electronic health records

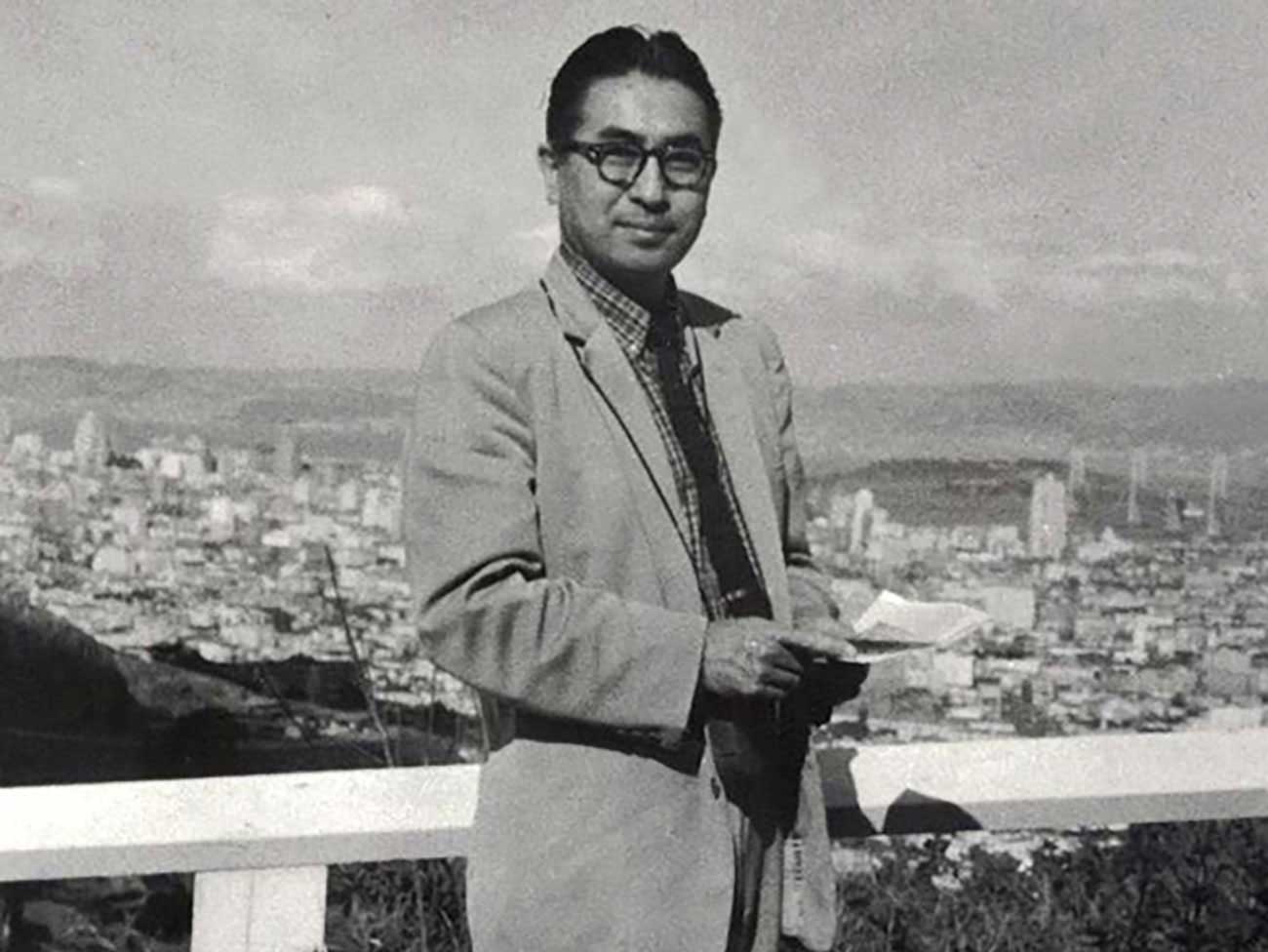

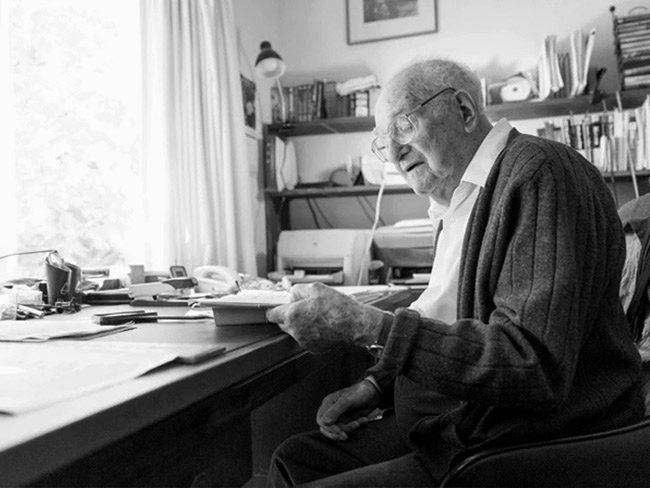

Dr. Collen is credited as the father of medical informatics, the field that pioneered the integration of computers and medicine.

Morris F. Collen, MD, was one of Kaiser Permanente’s founding physicians and a leader of the early multiphasic testing work. In 1966, he predicted that automation and computers would probably have “the greatest technological impact on medical science since the invention of the microscope.”

When the microscope was introduced in the 17th century, the ability to see details too small to be seen by the unaided eye transformed medicine.

He was right — but it took some time.

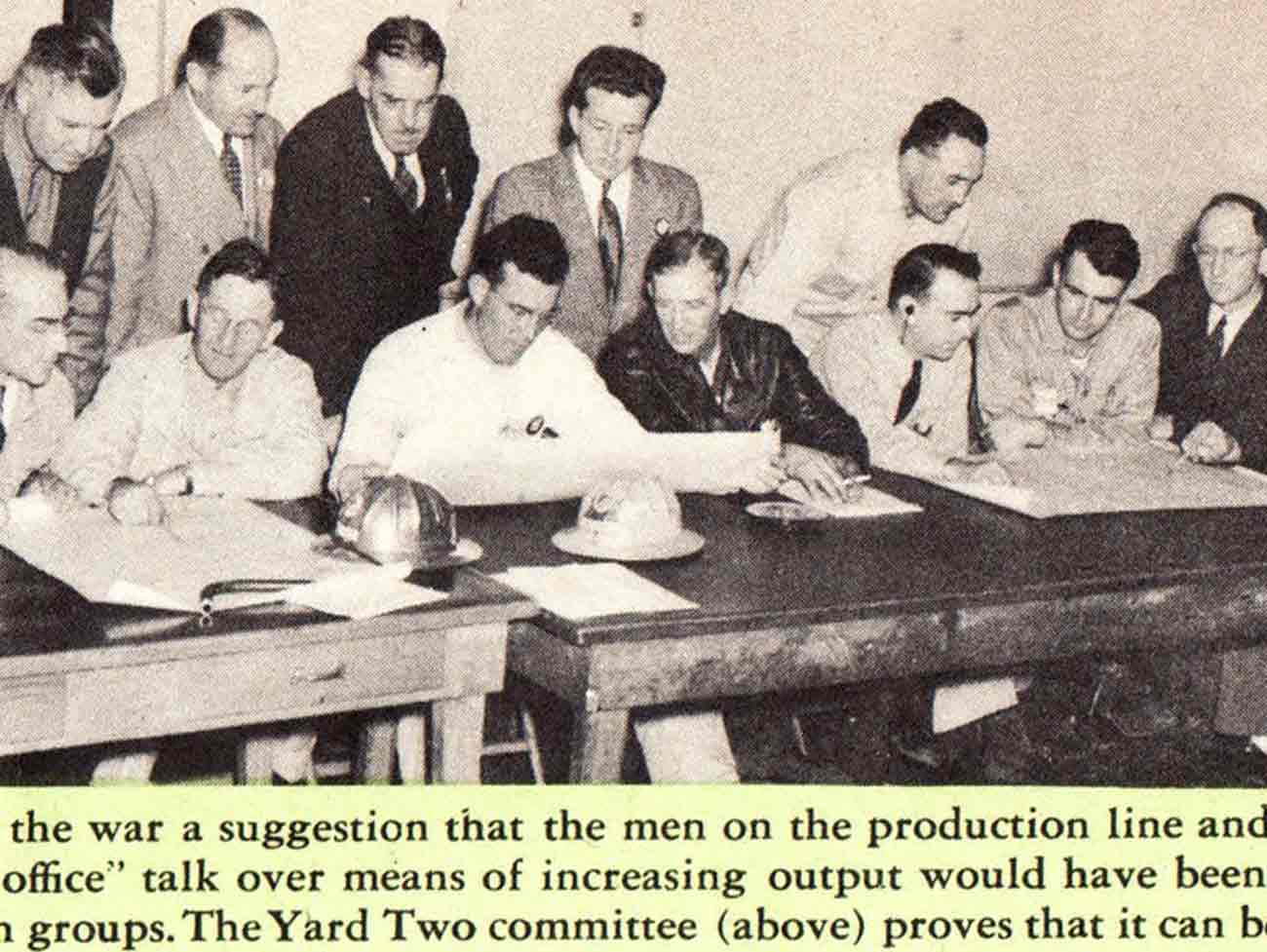

“I saw research as the face Kaiser Permanente presented to important people all over the country.” — Dr. Van Brunt, 2001

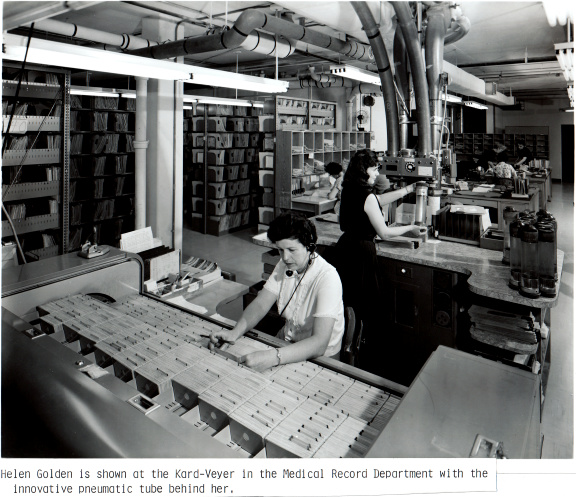

Years of collected multiphasic test data required proper storage and organization. Edmund Van Brunt, MD, appointed project chief of Kaiser Permanente’s Medical Data System in Oakland and San Francisco, started developing a computer database solution to store medical records for patient care and care delivery research.

In a 1996 interview, Dr. Van Brunt recalled, “The cards were put into a sorter at the end of the patient’s tour that day. Depending on the results, the cards would sort into ‘routine’ or ‘nonroutine’ and the patient was cared for accordingly. That was the first application of computers.”

Computer-processed patient health diagnostic tests stored in computer databases were an early version of the electronic health records to come.

The birth of the electronic health record system

In 1973, the Nixon administration abruptly canceled half of the computer project’s funding, leading to the shutdown of Kaiser Permanente’s San Francisco computer system. Despite such challenges, Dr. Van Brunt continued researching the application of computers and databases in medical care and health research.

By the late 1980s, another disruptive technology was emerging — the internet. To reduce errors and delays in care, the Northwest Permanente Medical Group started researching the potential for a regionwide medical health record system connected through the internet.

That initial research led to Kaiser Permanente’s 2003 launch of our proprietary electronic health record system. Today, it is the world’s largest civilian-operated electronic health record system in the country today— supporting the transformation of care delivery and connecting caregivers and patients in new and innovative ways.