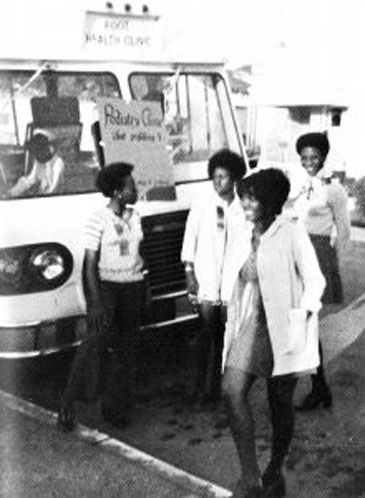

Mobile clinics: 'Health on wheels'

Kaiser Permanente mobile health vehicles brought care to people, closing gaps in access.

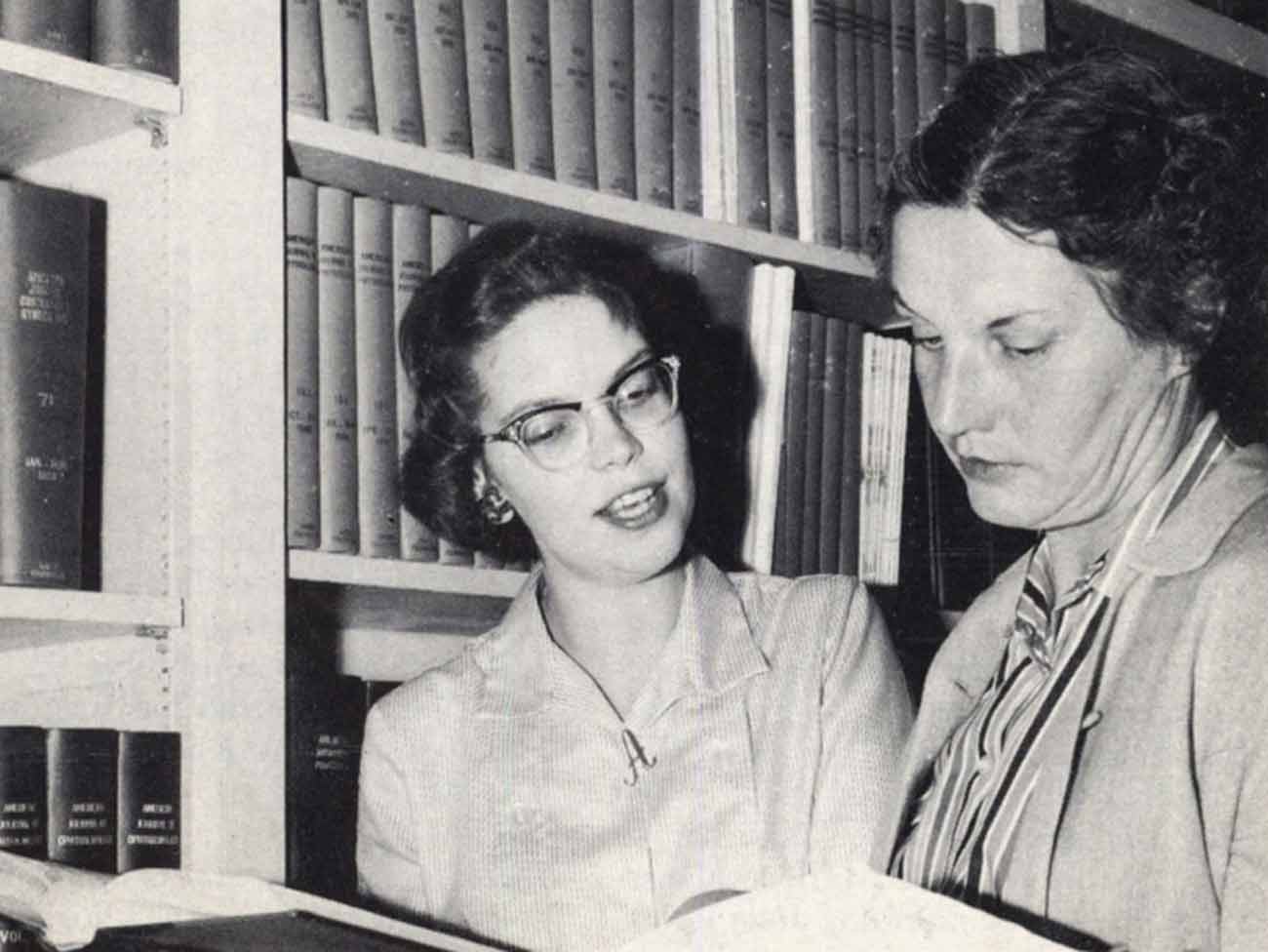

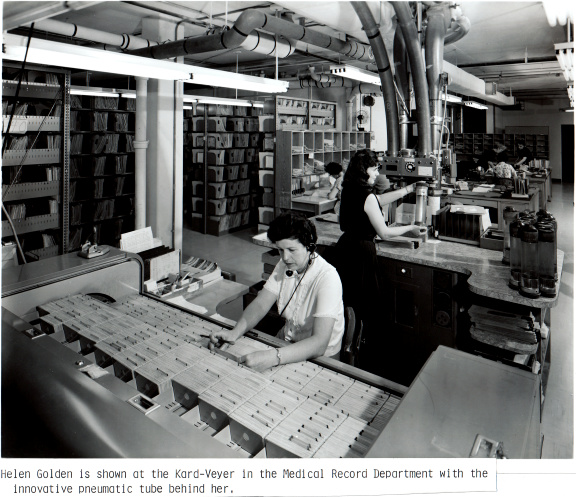

Kaiser Foundation School of Nursing student members of Kaiser Black Student Nurses’ Association serving on mobile Foot Health Clinic, 1972

If you can’t easily get patients to a clinic, what do you do?

Take the clinic to the patients.

This year, a Kaiser Permanente grant to the Healthy Smiles Mobile Dental Foundation in Fresno, California, paid for a brand-new recreational vehicle that’s been transformed into a dental clinic on wheels, complete with exam space, X-ray machines, and dental equipment. Several hygienists and dentists work inside the clinic, cleaning children’s teeth, and filling cavities.

It’s a model that’s been researched in the medical literature — and, because of its long history in mobile medicine, we know that it works.

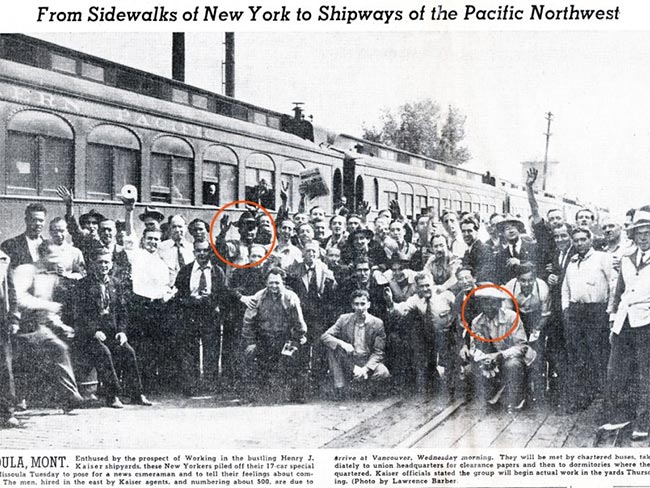

Early innovations in mobile medicine

In the early 1970s, Kaiser Permanente undertook several projects to test the feasibility of mobile health vans to serve underrepresented communities. One was rural, one was urban.

The rural example was “STARPAHC” — short for Space Technology Applied to Rural Papago Advanced Health Care. Kaiser Permanente and NASA partnered with Arizona’s Papago Indian Reservation to test the practicality of the emerging field of telemedicine. The project used the real needs of a remote earth-bound population to see how technology and routines could work when providing health care for astronauts in outer space.

And in very urban Oakland, California, Kaiser Foundation School of Nursing student members of Kaiser Black Student Nurses’ Association served on a mobile Foot Health Clinic in 1972.

Our medical care keeps moving

In 1988, Kaiser Permanente launched a Mobile Health Education and Screening Program in the Kansas City area. The 25-foot mobile van traveled to Kaiser Permanente medical offices as well as community organizations, local businesses, and public health fairs, where staff checked blood pressure and cholesterol levels, gave lifestyle assessment quizzes, and provided educational materials on a variety of health topics.

In Southern California, Kaiser Permanente had a similar program that operated out of a 38-foot Wellness Care-A-Van. It traveled as far north as Bakersfield and as far south as San Diego, reaching out to people in their communities, testing blood pressure and body fat. Frayne Rosenfield, Member Health Education administrator and Worksite Wellness Program coordinator, was enthusiastic about the service: “The van has been very well received. We see approximately 120 people a day, and the van is out 5 to 7 days a week.”

Kaiser Permanente also used the mobile van model for immunization drives in the 1990s.

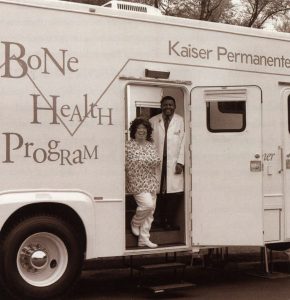

Kaiser Permanente’s 2001 Annual Report profiled a mobile bone-scan van used in the Mid-Atlantic states (complete with custom Maryland license plate “KPBONES”) to help members prevent and treat osteoporosis. It was staffed by Stephen Moki, radiology technologist and health educator, and Pat Brown, clinical assistant.

The Scan Van rotated among several Kaiser Permanente medical centers, spending 1 to 3 weeks at each facility before moving on. It proved to be a valuable outreach tool, and community organizations frequently called to request a visit from the van. Michael J. Moriarty, MD, vice president and associate medical director of Quality and Health Management, said, “I think that it helps to affirm our image as an innovator and a quality health care provider.”

Mobile health vans are in our future

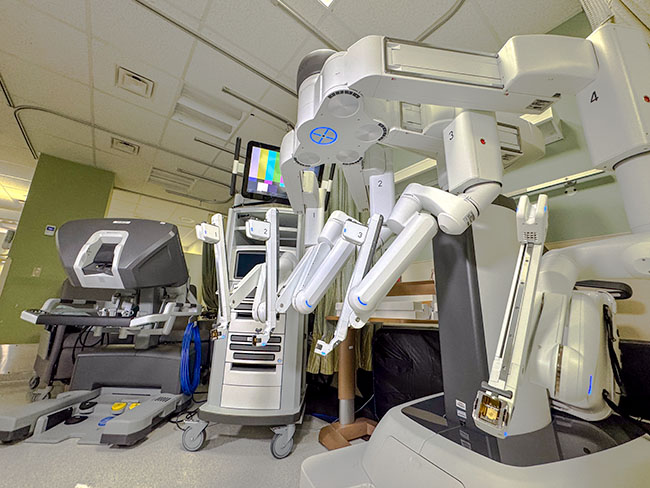

In 2009, Kaiser Permanente in Hawaii celebrated the arrival of a mobile health vehicle. The 500-square-foot, 10-wheeled rolling clinic was fully wired, equipped with our electronic health record system, a digital mammography unit, and video telemedicine capability.

The vehicle was designed to roam the Big Island, providing glucose and cholesterol screenings, mammograms, urinalysis, testing for sexually transmitted diseases, and vaccinations for the flu and pneumonia.

Billy Kenoi, the mayor of Hawaii County, praised the service when it was formally blessed July 2.

“I come from a 48,028 square mile island with incredible geographical and infrastructure challenges,” Kenoi said, “and the delivery of this Mobile Health Vehicle will improve not only the health care available on the island of Hawaii, but ultimately, the quality of life for our island residents.”

The use of mobile health vans is now integrated into our health plan, visiting urban worksites and rural communities and saving members time and travel for many of their medical needs.

As Frayne Rosenfield said in 1988, “The van is out 5 to 7 days a week.”

That’s about as accessible as health care can get.