Japanese-American doctors overcame internment setbacks

Despite restrictive hiring practices after World War II, Kaiser Permanente welcomed the innovation that comes with a diverse workforce by hiring Japanese physicians.

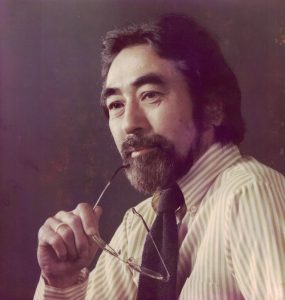

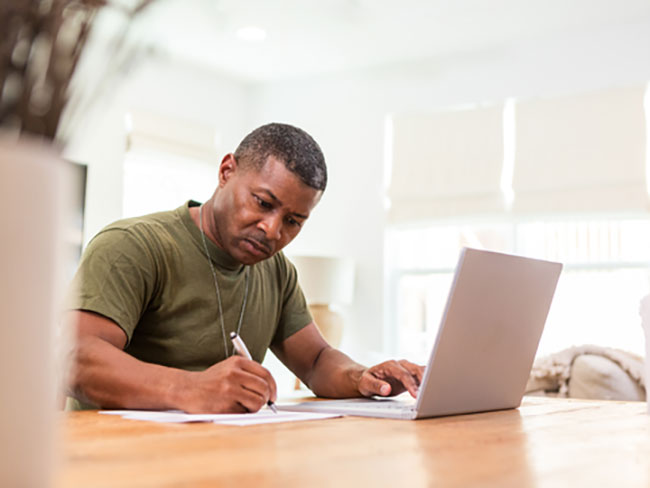

Dr. Isamu Nieda, circa 1955

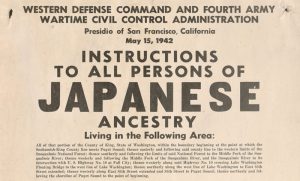

Ten weeks after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. This law, enacted on February 19, 1942, authorized the incarceration of Americans of Japanese descent and resident aliens from Japan. This measure only affected the American West; the U.S. military was given broad powers to ban any citizen from a fifty- to sixty-mile-wide coastal area stretching from Washington state to California and extending inland into southern Arizona. The order also authorized transporting identified citizens to military-run “internment” camps in California, Arizona, Washington state, and Oregon.

This controversial action was undertaken in the name of national security and affected almost 120,000 men, women, and children. The Order was suspended at the end of 1944 and internees were released, but many had lost their homes, savings, and businesses. Subsequent efforts by community and legal groups in the 1970s resulted in rescinding the Order and offering compensation to those affected, and legislation was passed to try to ensure that such a broad disruption of civil liberties would not happen again.

The impact of the war, and the suspension of basic human rights, personally affected two of Kaiser Permanente’s first Japanese American physicians. Once hired, they remained here their entire professional careers.

Isamu Nieda, MD (1918–1999)

Hired as a radiologist at Kaiser Permanente in 1954, retired in 1987

Isamu “Sam” Nieda was born in Ashland, Calif. (a small community in the central East Bay of San Francisco) in 1918 to Japanese-born parents. He was an undergraduate at the University of California, Berkeley, and then went to medical school at U.C. San Francisco. Partway through his studies he heard the news of Executive Order 9066.

According to Dr. Nieda’s late sister, the family held a meeting with Sam and determined together that he would leave the evacuation area to continue his studies. Family lore stated that he had to sell his microscope to pay for the journey and that the rest of his family chipped in as well. He then departed for Salt Lake City, where he worked briefly as an orderly, before continuing to Temple University in Philadelphia. The American Friends Service Committee (Quakers) helped Sam through the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council. This program worked with colleges and universities in the Midwest and Eastern States to admit qualified students from the camps and placed four thousand students before the war’s end.

Dr. Nieda completed medical school in 1944 at Temple University, and after World War II he served as a Venereal Disease Control Officer in Japan, working for the Public Health and Welfare department of the U.S. Army Medical Corps during the American occupation (1945-1952).

Dr. Nieda returned to the U.S. and worked as a radiologist at Kaiser Permanente’s San Francisco Medical Center for 33 years.

Dr. Nieda always identified as a U.C. student, so it was meaningful to the family when in 2009 UCSF granted honorary degrees to all Japanese American students from the Medical, Dental, and Pharmacological schools who had to stop their studies due to internment. (Sam had passed away ten years prior.)

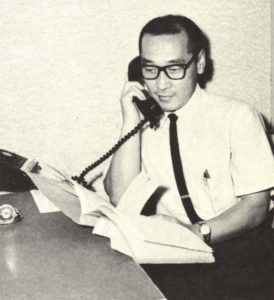

Ikuya T. Kurita, MD (1922-2005)

Hired in respiratory medicine at Kaiser Permanente in 1957, and retired in 1999.

Ikuya “Eek” Kurita, MD, was born in San Francisco in 1922 to Japanese-born parents. He attended U.C. Berkeley for two years until 1942, when he and his parents were relocated to an internment camp in Topaz, Utah. Internees could leave Topaz if they had a job or were admitted to school, so Kurita was able to complete his undergraduate degree at the University of Utah. He then served in the army from 1944 to 1947 and returned to the University of Utah where he graduated from medical school in 1950.

Dr. Kurita worked at Kaiser Permanente hospitals for 42 years, first in Oakland where he began as Chief of Emergency in 1957.

He was appointed chief of the Department of Emergency Services at the Oakland hospital in 1965, and in 1975 ran the new rehabilitation and educational clinic for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). An article in the KP Reporter described that program:

According to lkuya Kurita. MD., Emergency Department Chief at Oakland, and physician consultant for the Respiratory Care Clinic, the purpose of the program is to bridge the gap between acute hospital care and home management, with primary emphasis on reaching and helping patients before their condition erodes to the point of warranting hospital admission. “The clinic helps to fill the gap between acute care and what is often fragmented care,” says Dr. Kurita, who is a specialist in pulmonary diseases.

Dr. Kurita began working at the Martinez Medical Center in 1977 and retired from there in 1999.

Special thanks to the family of Isamu Nieda, retired Permanente physician Michael Gothelf, Dr. Ken Berniker of the TPMG Retired Physicians’ Association, scholar Elaine Elinson, and video producer Robert M. Horsting for their help with this article.