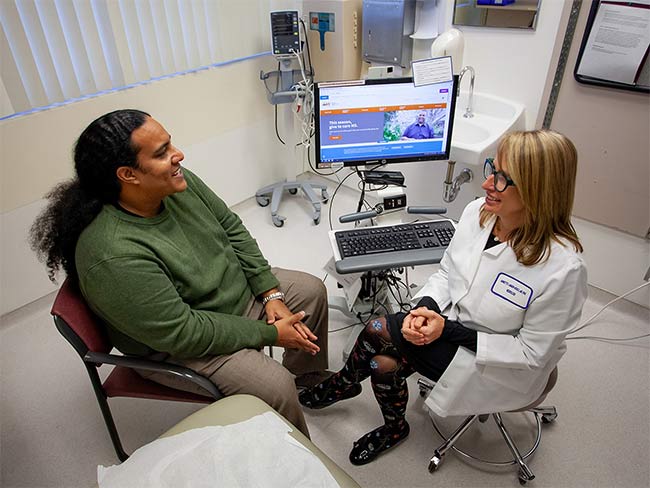

From paper to pixels — the new paradigm of electronic medical records

Transitioning to electronic health records introduced new approaches, skills, and understandings of patient records, improving the care experience.

Bess Kaiser Hospital medical record department, 1959. Receptionist in foreground identifies desired patient folder to be pulled from shelves in background; pneumatic tubes deliver files to nursing station.

Change rarely comes easily. People get used to doing things a certain way, and physicians are no exception. One such shift was a technology Kaiser Permanente adopted early on, creating patient medical records electronically rather than on paper.

In 2013 I interviewed Jim Gersbach, senior hospital communications consultant for Kaiser Permanente’s Northwest region. As their unofficial historian, Jim had accumulated many stories during his 28 years of service. This is an edited version of one of his learnings.

“EpiCare was forcing [doctors] to actually enter data on every patient; they couldn’t just leave it blank.” — Jim Gersbach

I can remember some of the older doctors didn’t even know how to type. That was the biggest barrier; they were doing the old hunt-and-peck because they had never needed to type. They just did dictation, or their nurses would type it up for them. The younger physicians were very eager to adopt computerized medical records because they were a little bit more familiar with computers.

But after 1998 the Northwest Permanente Medical Group had done some survey work — [which had some] pushback — and heard that ‘This is adding to our day; it’s 45 minutes more a day to try and enter all this stuff in.’ People were complaining that ‘When I did paper, I didn’t take so long to do all this stuff, so it’s not a time saver for us.’

We started looking at that and found that sometimes when doctors would get busy, they would just sort of scribble something illegible in the chart, and send it off because they could get out of their office faster. EpiCare was forcing them to enter data on every patient; they couldn’t just leave it blank. That was a major ‘Aha!’ moment. What became evident was, ‘Wait a minute; we’re not necessarily charting everything we’re supposed to.’ And the computerized system helped.

Not only did it make everything legible, but it forced clinicians to put something in; you had to type something in, or it wouldn’t advance you forward. It improved the quality of the data.

In the Northwest, at the time EpiCare was being adopted, the doctors were very free to say what they didn’t like about it. But despite all the grumbling about ‘It’s adding to our length of the day,’ when we asked, “Would you ever want to go back to paper?” they said ‘Absolutely not! I couldn’t live without the system, because it provides me everything I need to know for the patient.’ They very quickly saw the value of it as a clinical aid.

-

Social Share

- Share From paper to pixels — the new paradigm of electronic medical records on Pinterest

- Share From paper to pixels — the new paradigm of electronic medical records on LinkedIn

- Share From paper to pixels — the new paradigm of electronic medical records on Twitter

- Share From paper to pixels — the new paradigm of electronic medical records on Facebook

- Print From paper to pixels — the new paradigm of electronic medical records

- Email From paper to pixels — the new paradigm of electronic medical records

February 24, 2026

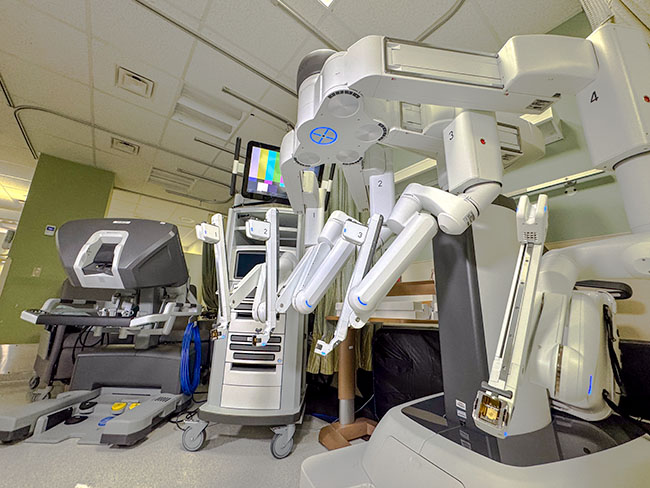

Expanding outpatient robotic surgery in Colorado

More outpatient robotic surgery at Kaiser Permanente’s Colorado surgery …

April 30, 2025

A history of trailblazing nurses

Nursing pioneers lay the foundation for the future of Kaiser Permanente …

April 16, 2025

Sidney R. Garfield, MD: Pioneer of modern health care

Kaiser Permanente’s co-founding physician spread prepaid care and the idea …

March 25, 2025

AI in health care: 7 principles of responsible use

These guidelines ensure we use artificial intelligence tools that are safe …

September 19, 2024

First look at new Lakewood facilities

New medical offices will enhance the health care experience for members …

July 2, 2024

Reducing cultural barriers to food security

To reduce barriers, Food Bank of the Rockies’ Culturally Responsive Food …

June 28, 2024

Health Action Summit highlights mental health opportunities

The Kaiser Permanente Colorado Health Action Summit gathered nonprofits, …

June 3, 2024

A call to ‘Connect’ for cancer prevention research

Participate in a study to help uncover the causes of cancer and how to …

May 3, 2024

Henry J. Kaiser: America’s health care visionary

Kaiser was a major figure in the construction, engineering, and shipbuilding …

April 8, 2024

Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream is alive at Kaiser Permanente

Greg A. Adams, chair and chief executive officer of Kaiser Permanente, …

March 19, 2024

Fostering responsible AI in health care

With the right policies and partnerships, artificial intelligence can lead …

February 13, 2024

A legacy of life-changing community support and partnership

The Kaiser Permanente Watts Counseling and Learning Center started as a …

February 2, 2024

Expanding medical, social, and educational services in Watts

Kaiser Permanente opens medical offices and a new home for the Watts Counseling …

January 31, 2024

Prioritizing policies for health and well-being in Colorado

CityHealth’s 2023 Annual Policy Assessment awards cities for their policies …

December 20, 2023

Research transforms care for people with multiple sclerosis

Our researchers are leading the way to more effective, affordable, and …

December 6, 2023

Leaders named among health care’s most influential

Greg A. Adams; Maria Ansari, MD, FACC; and Ramin Davidoff, MD, have been …

October 23, 2023

The future of health care is digital

Nari Gopala, Kaiser Permanente’s chief digital officer, answers 3 questions …

October 17, 2023

How Kaiser Permanente evolved

Sidney R. Garfield, MD, and Henry J. Kaiser came together to pioneer an …

October 4, 2023

An easier way to manage multiple prescriptions

If you have an ongoing health condition, you know it can be tricky to keep …

September 27, 2023

10 school districts receive next round of RISE grants

The Thriving Schools program helps educators and students in Colorado integrate …

September 13, 2023

Transforming the medical record

Kaiser Permanente’s adoption of disruptive technology in the 1970s sparked …

May 2, 2023

Women lead an industrial revolution at the Kaiser Shipyards

Early women workers at the Kaiser shipyards diversified home front World …

April 25, 2023

Hannah Peters, MD, provides essential care to ‘Rosies’

When thousands of women industrial workers, often called “Rosies,” joined …

November 11, 2022

A history of leading the way

For over 75 innovative years, we have delivered high-quality and affordable …

November 11, 2022

Pioneers and groundbreakers

Learn about the trailblazers from Kaiser Permanente who shaped our legacy …

November 11, 2022

Our integrated care model

We’re different than other health plans, and that’s how we think health …

November 11, 2022

Our history

Kaiser Permanente’s groundbreaking integrated care model has evolved through …

October 14, 2022

Contact Heritage Resources

October 6, 2022

We’re a Fast Company Innovation by Design winner

Kaiser Permanente is the first health care organization to win Design Company …

October 1, 2022

Innovation and research

Learn about our rich legacy of scientific research that spurred revolutionary …

May 26, 2022

Nurse practitioners: Historical advances in nursing

A doctor shortage in the late 1960s and an innovative partnership helped …

September 10, 2021

‘Baby in the drawer’ helped turn the tide for breastfeeding

This innovation in rooming-in allowed newborns to stay close to mothers …

August 25, 2021

Kaiser Permanente’s history of nondiscrimination

Our principles of diversity and our inclusive care began during World War …

July 22, 2021

A long history of equity for workers with disabilities

In Henry J. Kaiser’s shipyards, workers were judged by their abilities, …

June 2, 2021

Path to employment: Black workers in Kaiser shipyards

Kaiser Permanente, Henry J. Kaiser’s sole remaining institutional legacy, …

February 22, 2021

The Permanente Richmond Field Hospital

Forlorn and all but forgotten, it played a proud role during the World …

September 28, 2020

A legacy of disruptive innovation

Proceeds from a new book detailing the history of the Kaiser Foundation …

August 26, 2020

Kaiser Permanente’s pioneering nurse-midwives

The 1970s nurse-midwife movement transformed delivery practices.

July 30, 2020

Books and publications about our history

Interested in learning more about the history of Kaiser Permanente and …

May 18, 2020

Nurses step up in crises

Kaiser Permanente nurses have been saving lives on the front lines since …

November 8, 2019

Swords into stethoscopes — veterans in health professions

Kaiser Permanente has actively hired veterans in all capacities since World …

August 28, 2019

When labor and management work side by side

From war-era labor-management committees to today’s unit-based teams, cooperation …

August 2, 2019

Thriving with 1960s-launched KFOG radio

Kaiser Broadcasting radio connected listeners, while TV stations brought …

June 5, 2019

Breaking LGBT barriers for Kaiser Permanente employees

“We managed to ultimately break through that barrier.” — Kaiser Permanente …

March 29, 2019

Equal pay for equal work

Kaiser shipyards in Oregon hired the first 2 female welders at equal pay …

February 5, 2019

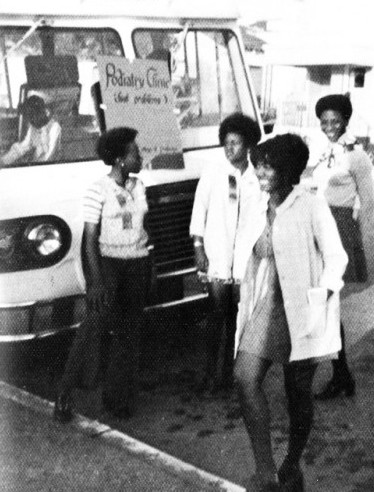

Mobile clinics: 'Health on wheels'

Kaiser Permanente mobile health vehicles brought care to people, closing …

December 10, 2018

Southern comfort — Dr. Gaston and The Southeast Permanente Medical Group

Local Atlanta physicians built community relationships to start Kaiser …

May 30, 2018

John Graham Smillie, MD, pediatrician and innovator

Celebrating the life of a pioneering pediatrician who inspired the baby …

April 30, 2018

Nursing pioneers leads to a legacy of leadership

Kaiser Foundation School of Nursing students learned a new philosophy emphasizing …

April 19, 2018

Wasting nothing: Recycling then and now

Environmentalism was a common practice at the Kaiser shipyards long before …

April 12, 2018

Harold Hatch, health insurance visionary

The founding of Kaiser Permanente's concept of prepaid health care in the …

March 26, 2018

5 physicians who made a difference

Meet 5 outstanding doctors who advanced the practice of medical care with …

March 13, 2018

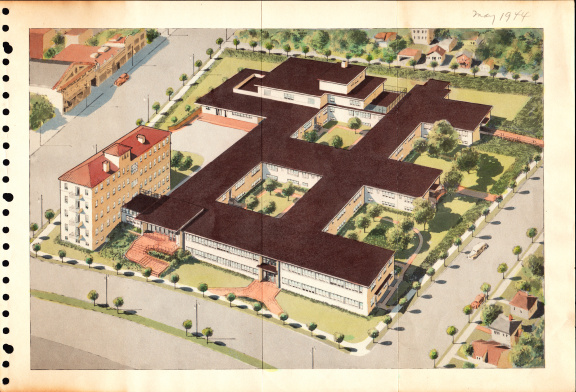

Henry J. Kaiser and the new economics of medical care

Kaiser Permanente’s co-founder talks about the importance of building hospitals …

March 8, 2018

Slacks, not slackers — women’s role in winning World War II

Women who worked in the Kaiser shipyards helped lay the groundwork for …

February 22, 2018

The amazing true story of Park Ranger Betty Reid Soskin

She is the oldest national park ranger in the country with a legacy of …

December 19, 2017

From boats to books: A history of Kaiser Permanente’s medical libraries

Kaiser Permanente librarians are vital in helping clinicians remain updated …

November 7, 2017

Patriot in pinstripes: Honoring veterans, home front, and peace

Henry J. Kaiser's commitment to the diverse workforce on the home front …

October 12, 2017

An experiment named Fabiola

Health care takes root in Oakland, California.

September 29, 2017

Harbor City Hospital: Beachhead for labor health care

The story of Kaiser Permanente's South Bay Medical Center finds its roots …

August 15, 2017

Sidney R. Garfield, MD, on medical care as a right

Hear Kaiser Permanente’s physician co-founder talk about what he learned …

August 10, 2017

‘Good medicine brought within reach of all'

Paul de Kruif, microbiologist and writer, provides early accounts of Kaiser …

July 14, 2017

Kaiser’s role in building an accessible transit system

Harold Willson, an employee, and an advocate for accessible transportation, …

July 7, 2017

Mending bodies and minds — Kabat-Kaiser Vallejo

The expanded new location provided care to a greater population of members …

June 23, 2017

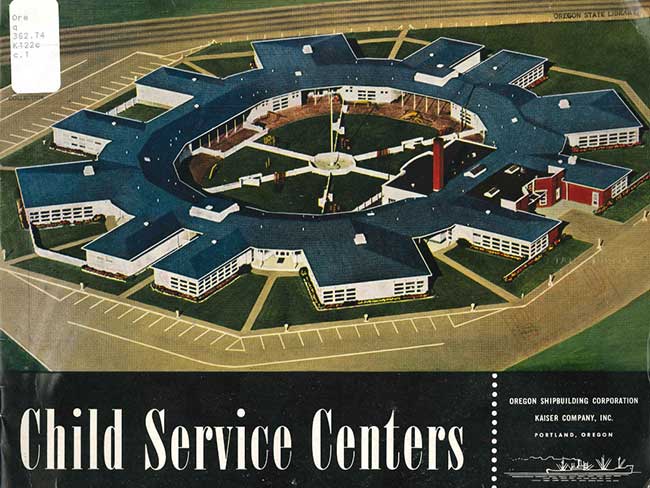

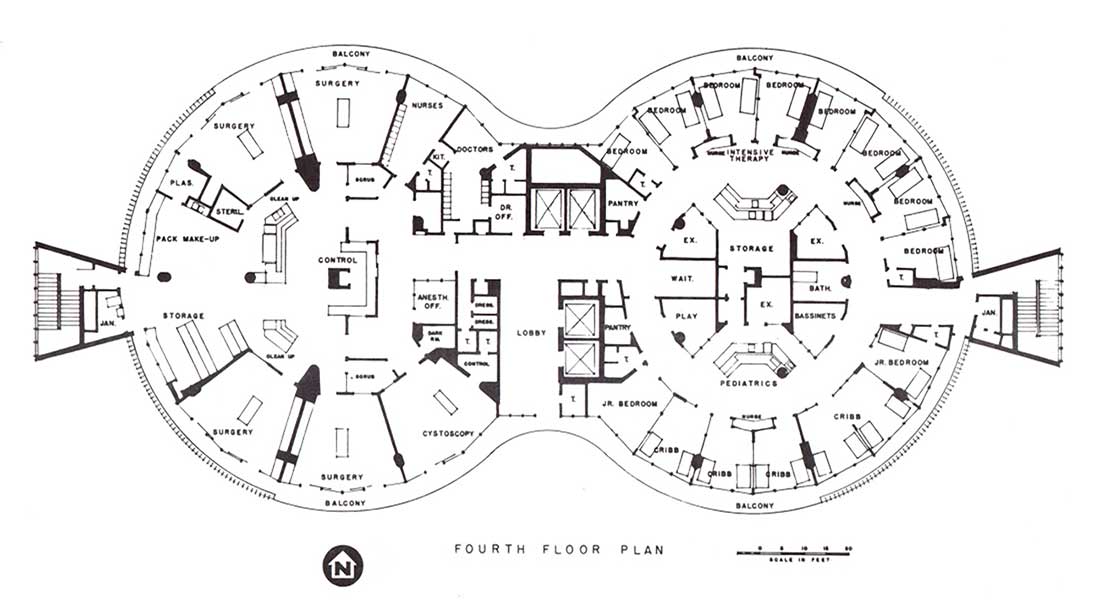

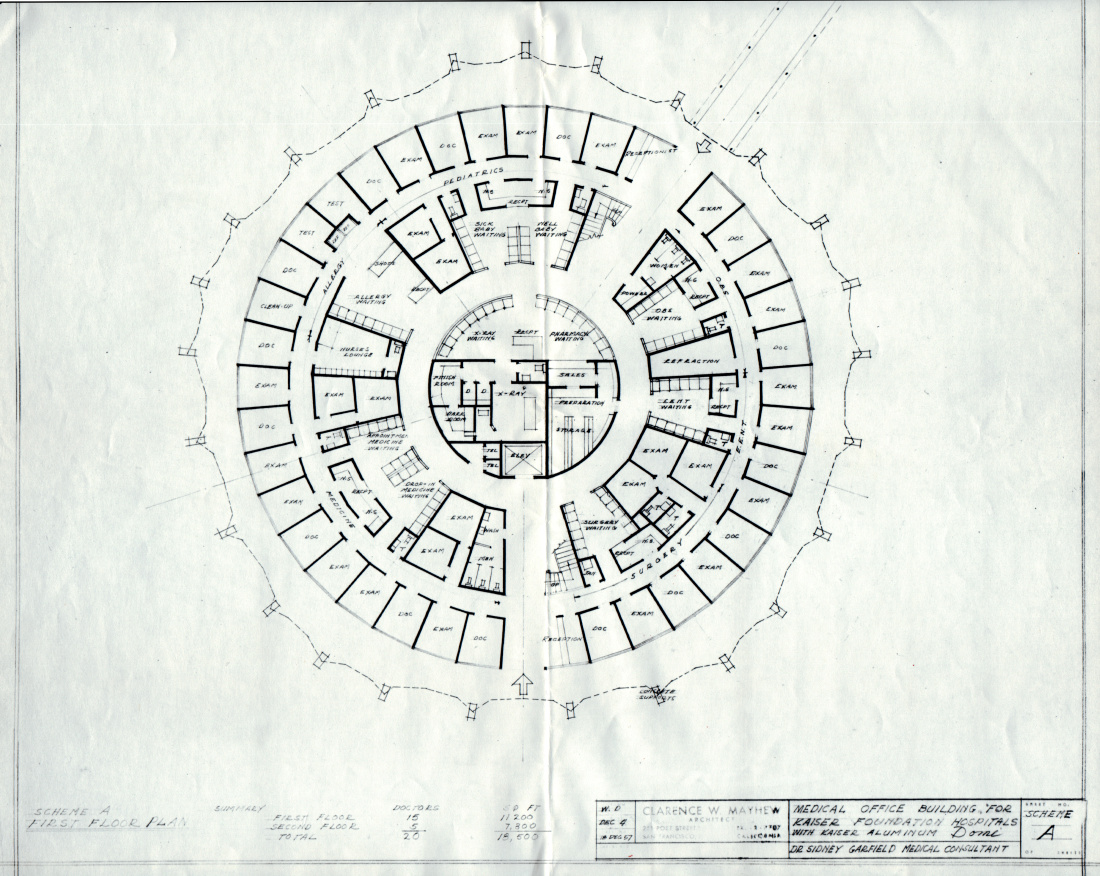

No getting round it: An innovative approach to building design

Kaiser Permanente incorporated innovative circular architectural designs …

June 14, 2017

Kabat-Kaiser: Improving quality of life through rehabilitation

When polio epidemics erupted, pioneering treatments by Dr. Herman Kabat …

June 9, 2017

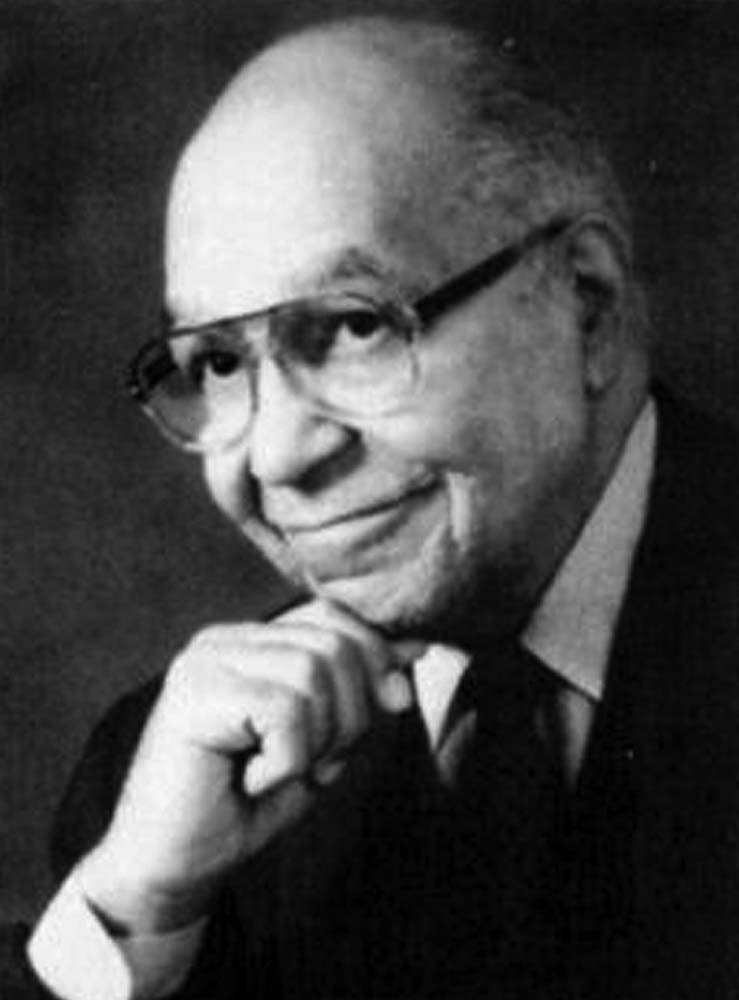

Edmund (Ted) Van Brunt, pioneer of electronic health records, dies at age …

Throughout his career, Dr. Van Brunt applied computers and databases in …

May 4, 2017

How a Kaiser Permanente nurse transformed health education

Kaiser Permanente's Health Education Research Center and Health Education …

March 22, 2017

Kaiser Permanente and Group Health Cooperative: Working together since …

The formation of Kaiser Permanente Washington comes from longstanding collaboration, …

March 7, 2017

Beatrice Lei, MD: From Shantou, China, to Richmond, California

She served as a role model and inspiration to the women physicians and …

March 1, 2017

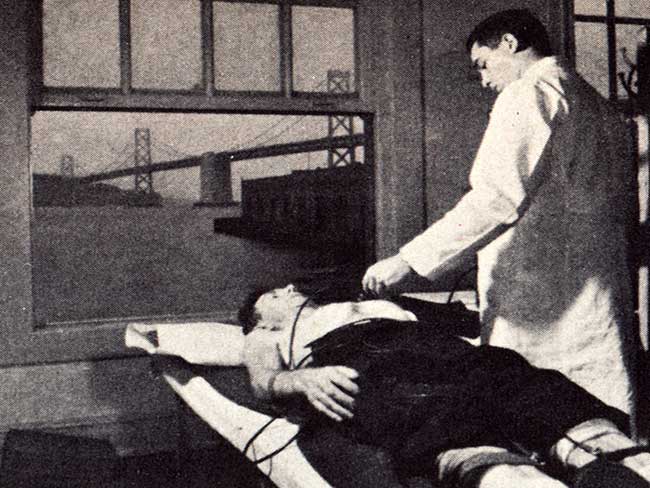

Screening for better health: Medical care as a right

When industrial workers joined the health plan, an integrated battery of …

February 17, 2017

Experiments in radial hospital design

The 1960s represented a bold step in medical office architecture around …

February 3, 2017

Ellamae Simmons — trailblazing African American physician

Ellamae Simmons, MD, worked at Kaiser Permanente for 25 years, and to this …

January 27, 2017

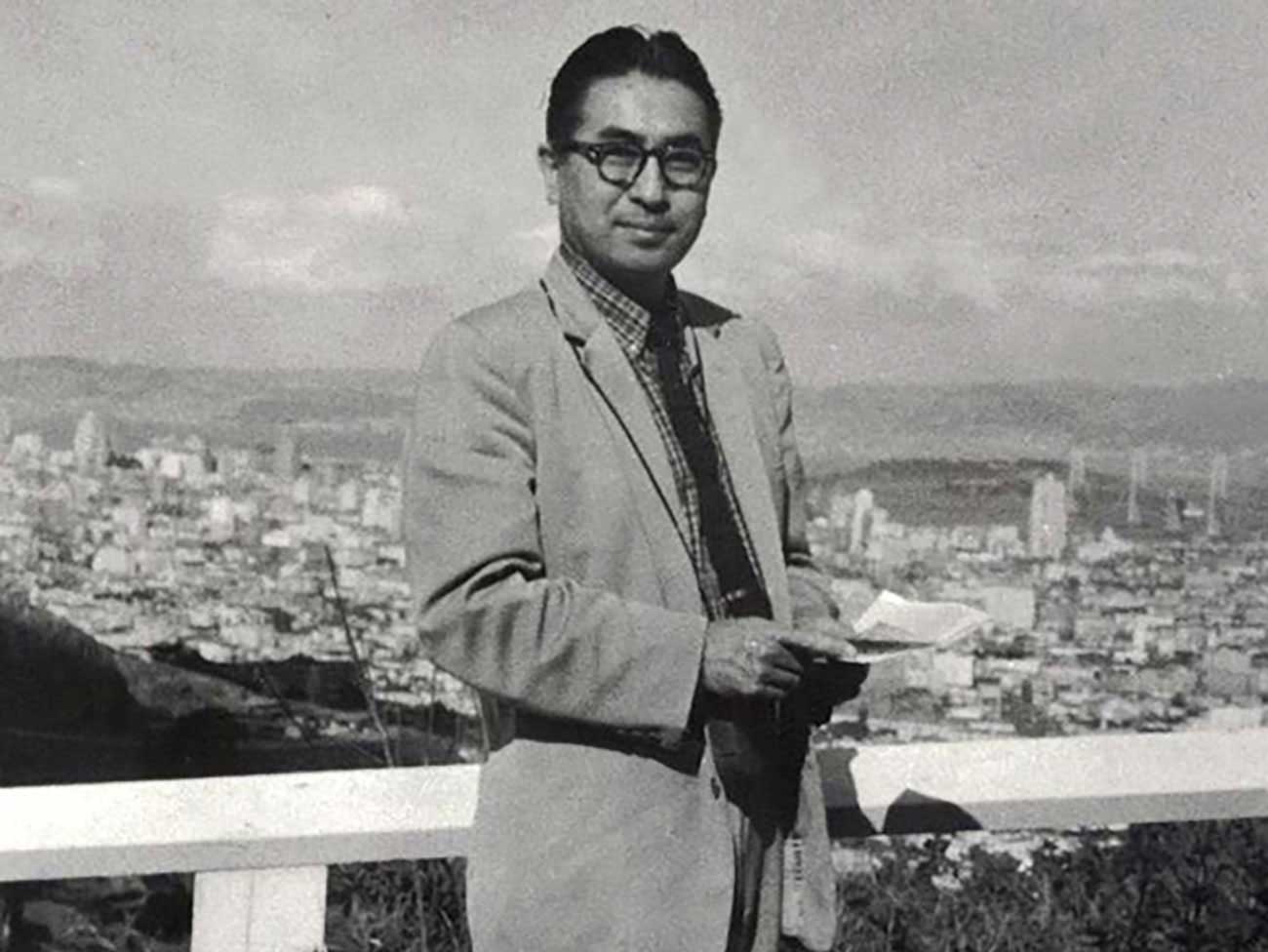

Japanese-American doctors overcame internment setbacks

Despite restrictive hiring practices after World War II, Kaiser Permanente …

November 16, 2016

Betty Reid Soskin honored with lifetime achievement award

The California Studies Association presents the Carey McWilliams Award …

October 17, 2016

Kaiser Motors in Oakland — “We sell to make friends.”

In 1946 Henry J. Kaiser Motors purchased half a square block in downtown …

October 12, 2016

Kaiser’s geodesic dome clinic

There are hospital rounds, and there are round hospitals.

May 5, 2016

Male nursing pioneers

Groundbreaking male students diversify the Kaiser Foundation School of …

April 20, 2016

Henry J. Kaiser’s environmental stewardship

Since the 1940s, Kaiser Industries and Kaiser Permanente have a long history …

November 13, 2015

Dr. Morris Collen’s last book on medical informatics

The last published work of Morris F. Collen, MD, one of Kaiser Permanente’s …

September 23, 2015

Kaiser Permanente and NASA — taking telemedicine out of this world

Kaiser Permanente International designs, develop, and test a remote health …

July 22, 2015

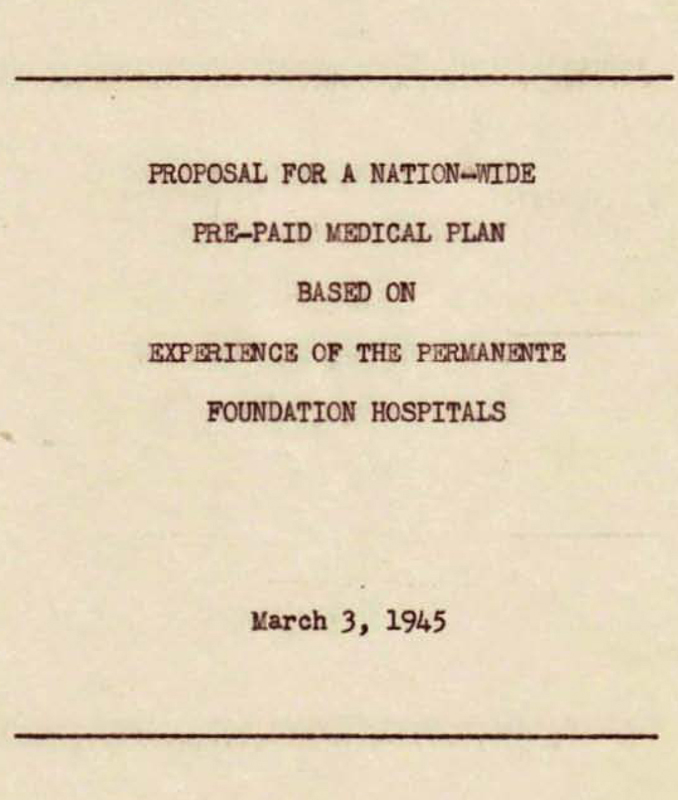

Kaiser Permanente as a national model for care

Kaiser Permanente proposed a revolutionary national health care model after …

July 21, 2015

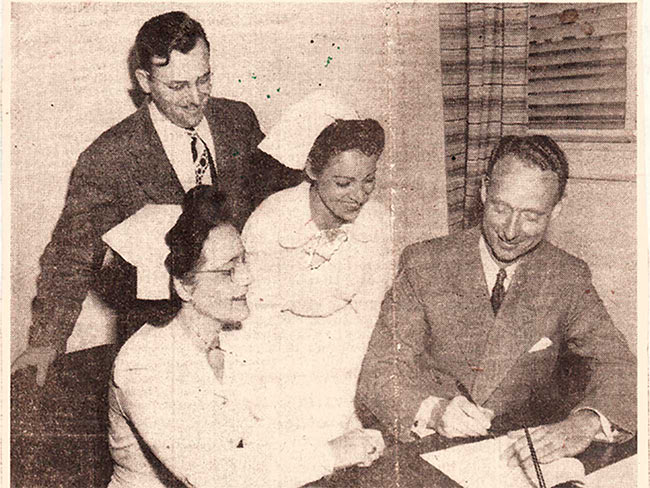

Kaiser Permanente's early support from labor

Experiencing the Kaiser Permanente health plan led labor unions to support …

July 20, 2015

Opening the Permanente plan to the public

On July 21, 1945, Henry J. Kaiser and Dr. Sidney Garfield offered the health …

July 1, 2015

Sculpture dedicated to Kaiser Nursing School

The Kaiser Foundation School of Nursing sculpture near Kaiser Oakland hospital …

May 6, 2015

Celebrating Betty Runyen — Kaiser Permanente’s ‘founding nurse’

In a desert hospital during the Great Depression, Betty Runyen overcame …

April 27, 2015

Eugene Hickman, MD — Pioneering Black physician

Dr. Hickman had a long career at Kaiser Permanente, becoming president …

April 24, 2015

2 historical reflections on Kaiser Permanente

April 2, 2015

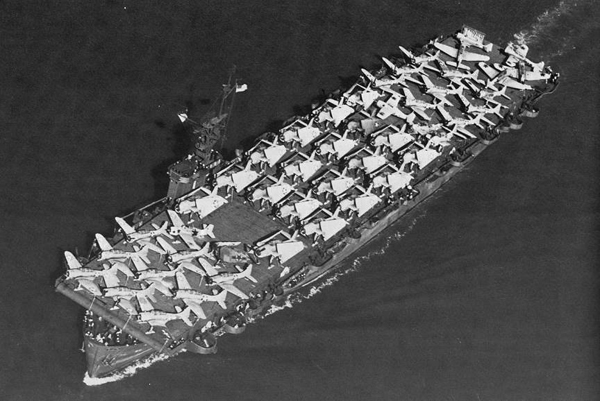

Henry Kaiser’s escort carriers and the Battle of Leyte Gulf

January 9, 2015

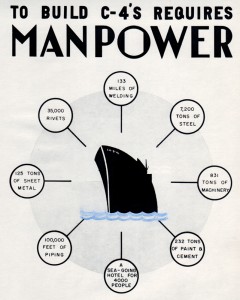

The World War II Kaiser Richmond shipyard labor force

December 16, 2014

Henry J. Kaiser on veteran employment and benefits

December 11, 2014

Henry J. Kaiser, geodesic dome pioneer

October 8, 2014

Breast cancer isn’t just a woman’s issue

July 23, 2014

Kaiser shipyards pioneered use of wonder drug penicillin

Though supplies for civilians were limited, Dr. Morris Collen’s wartime …

June 24, 2014

Kaiser Permanente's first hospital changes and grows

A collection of vintage photos that chronicle the evolution of Oakland …

June 20, 2014

Old hospital holds memories of Kaiser Permanente’s past

Rebuilt Oakland Medical Center to open for business.

May 13, 2014

Henry J. Kaiser sticks up for union labor at Brewster Aeronautical

May 5, 2014

Black nurses get together to forge their own future

California African American nurses organize in early 1970s to address health …

May 1, 2014

Beloved nurse earned place in Kaiser Permanente history

Jessie Cunningham, the first Black nursing supervisor at Oakland Medical …

February 18, 2014

Alva Wheatley: Champion of Kaiser Permanente diversity

Third in a series marking Black History Month.

January 31, 2014

Raleigh Bledsoe, MD: First Black radiologist west of Rockies

Dr. Bledsoe became the first Black physician for Southern California Permanente …