Quality of care: always foremost in minds of Kaiser Permanente leaders

Kaiser Permanente doctors applied research and innovation to implement quality of care assessments.

San Francisco pediatrician John Smillie checks the health of two young sisters and their doll, circa 1960.

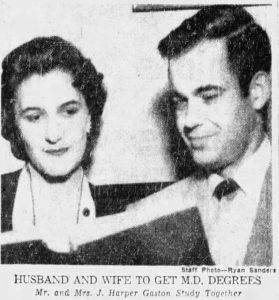

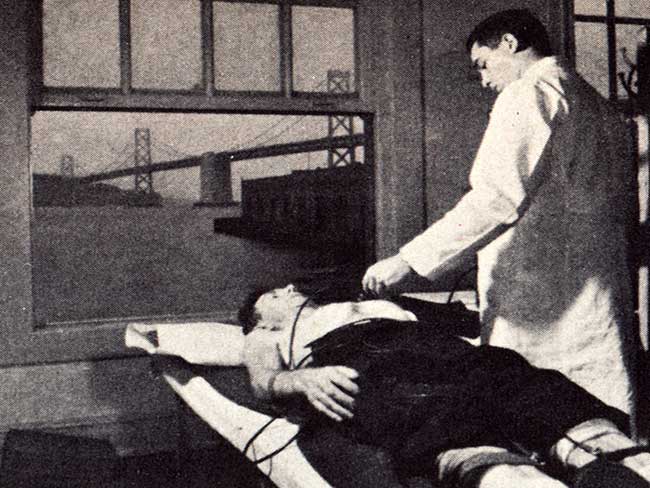

Hannah Peters, MD, a women’s physician in the World War II Kaiser Shipyards, studied the female workers’ adaptation to heavy labor.

In the beginning of the modern era of medicine, there were doctors and patients. To judge the quality of care was to ask: Did the patient live? Is the patient thriving? Doctors had little science to back up their methods. They followed conventions and did what they thought was best for the patient. If a doctor went wrong, no formal mechanism existed to correct his (or her) ways.

Hard to imagine how we got from such early simplicity to today’s complicated state of quality affairs. Our 2012 definition of quality encompasses a myriad of considerations: timely access to care, science-based treatment, adherence to well-defined practice protocols, and appropriate use of technology. Preventive care screenings, such as mammograms and colon studies to catch cancer early, and access to health education so patients can learn to avoid disease are key factors in assessing the quality of care of a provider organization.

Figuring out the best way to judge the quality of care has been a monumental quest pursued by health care providers and consumers alike since the early 1950s. This pursuit has been embraced by numerous medical, government, and consumer agencies in the past 50-plus years, creating a veritable alphabet soup of regulatory and review/rating organizations with varying degrees of effectiveness and longevity.

Further complicating the issue of quality is the fact that everything doctors, hospitals, and health plans undertake — staff recruitment and education, research, and technology upgrades — affects quality. So it’s difficult, if not impossible, to talk about quality without looking at these topics as well. So the subject of quality is all-encompassing and, at times, overwhelming.

A case study of Kaiser Permanente’s initiatives over the decades to assess and improve quality of care reveals many different approaches and different boards and committees formed to respond to industry trends and to ultimately crack the quality nut.

In many instances, Kaiser Permanente was in the forefront of the various quality movements, often intending to prove its worth to a skeptical world of traditionalists who didn’t like prepaid group practice. At other times, Permanente was pioneering new methods of care delivery and conducting crucial quality research that would lead the way for what came to be called quality assurance, initially for health maintenance organizations (HMO) and later for all forms of managed care.

Permanente physicians came from academic tradition

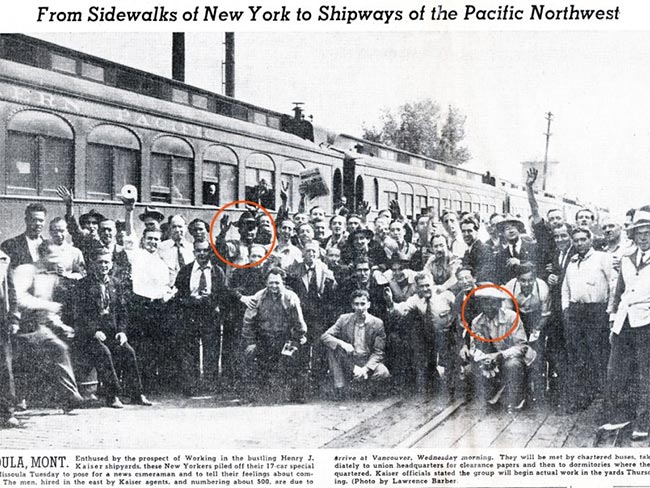

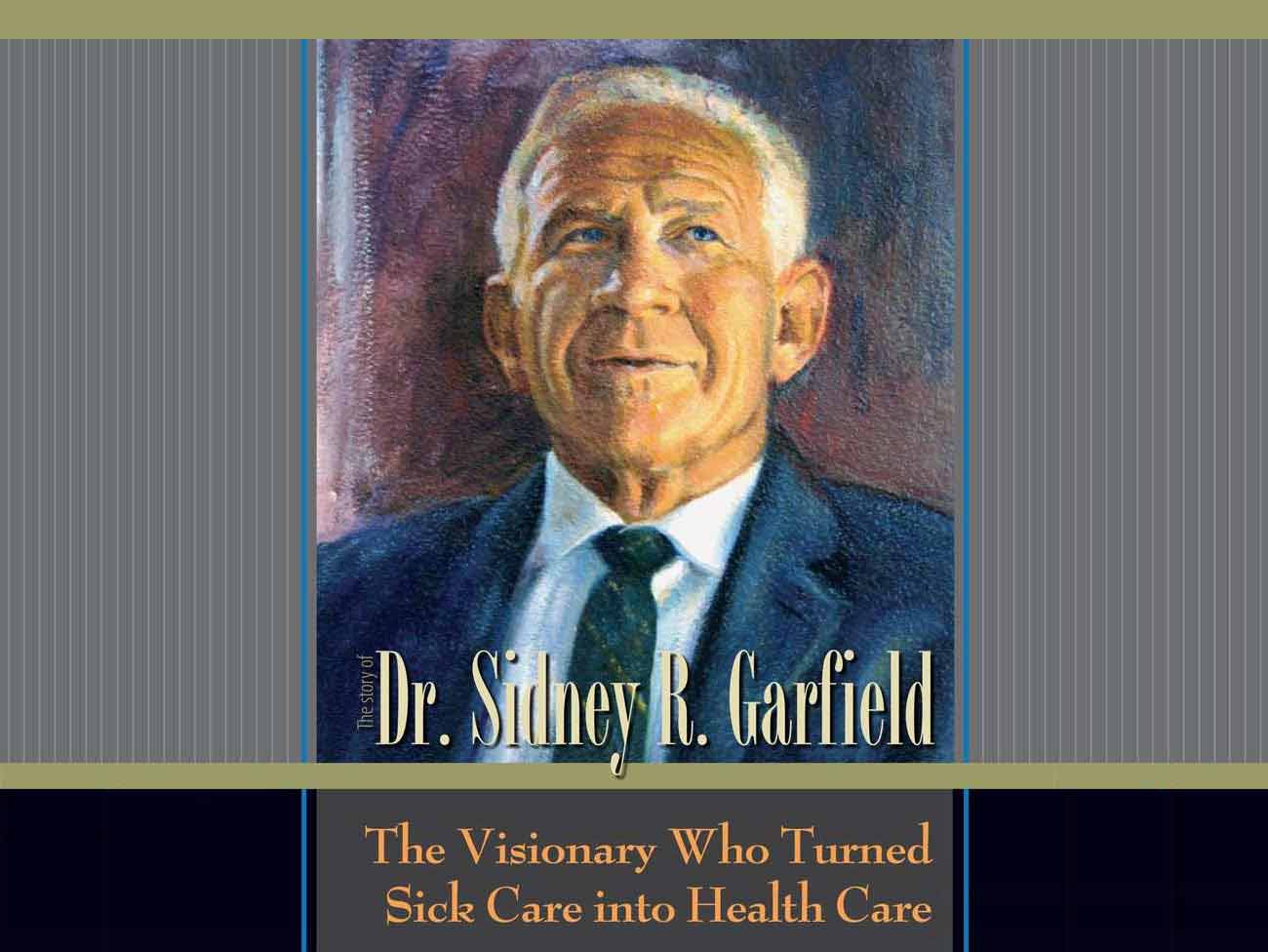

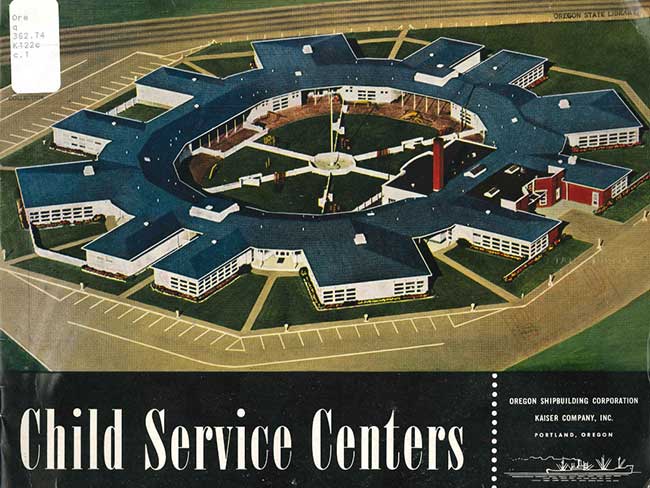

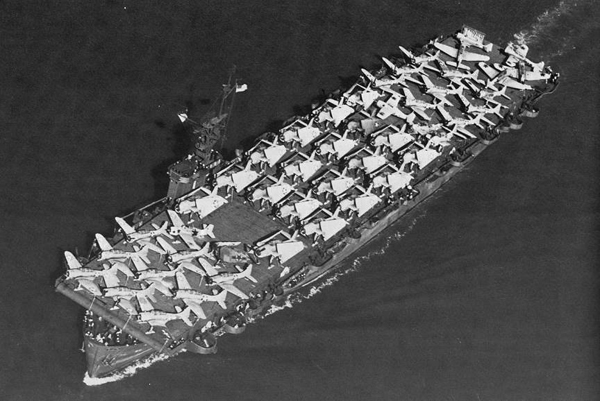

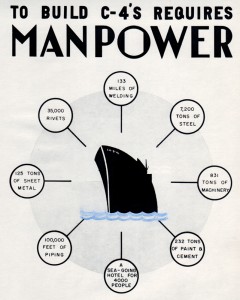

Starting out in the World War II West Coast shipyards, Sidney Garfield and Henry Kaiser knew the quality of care had to be the best possible to make sure the often sickly workers would be fit for dirty, hard and stressful work. So they used the latest methods they knew — and could learn about through research — to be on top of their medical game. Coming from an academic medical center at Los Angeles County General Hospital, Garfield understood the benefits of research, collaboration and continuous quality improvement, a term unheard of at the time.

Garfield hired like-minded contemporaries, such as surgeon Cecil Cutting, internist Morris Collen, and gynecologist Hannah Peters, all socially conscious and oriented toward innovation, to carry out the wartime program. Learning all the time, these physicians developed new treatments and published their results during and after the war.

Inundated with pneumonia patients, Collen uncovered new ways to treat the often deadly condition. Treating pneumonia patients with horse serum and sulfa drugs, Collen was able to save many lives, even before the “wonder drug” penicillin became available to treat civilians at war’s end.

Hannah Peters, a German native who migrated to New York in 1934, studied women shipyard workers’ ability to adapt to heavy, industrial work. She noted how a woman’s menstrual cycle was affected by the carbohydrate-rich diet necessitated by the physical demands of welding and other shipyard jobs.

She and her colleague gynecologist Duncan Footer published their results in a 1946 issue of the Kaiser Foundation Bulletin, as well as in national medical journals. Peters went on to become the leader of the Laboratory for Reproductive Biology in Copenhagen and published many articles on women’s health.

Postwar health plan set aside funds for research and education

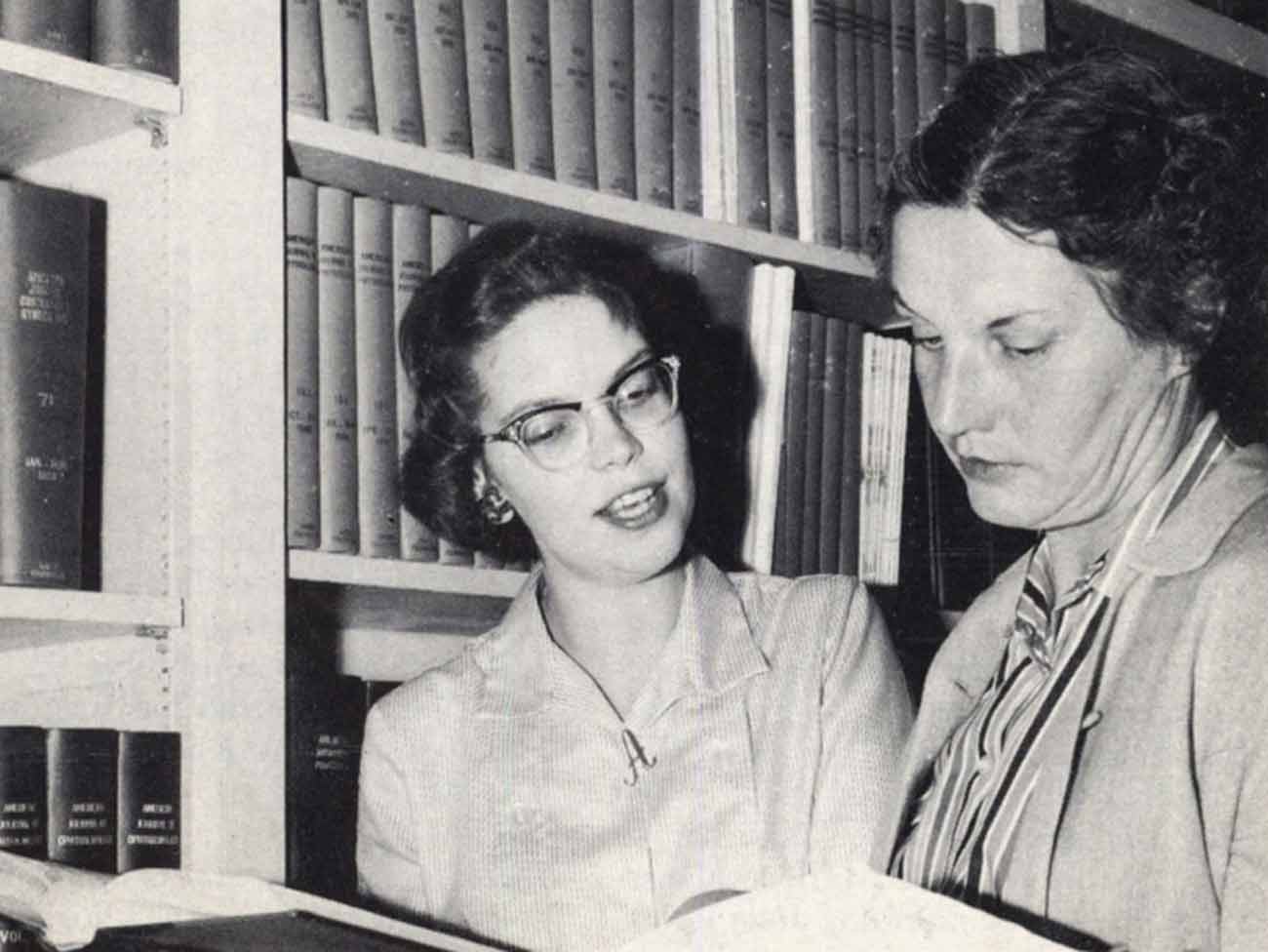

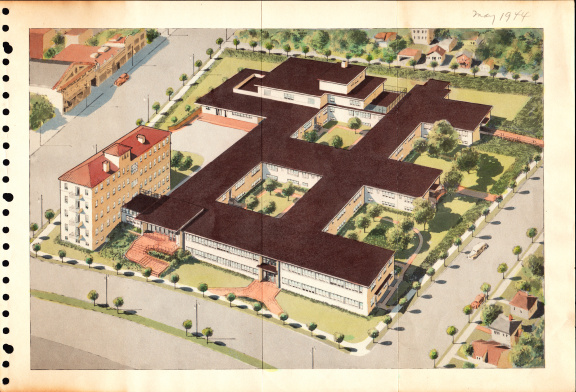

After the war when the Permanente health plan was opened to the public, quality of care continued to be a top priority. With 5% of Kaiser Foundation revenues guaranteed by its charter for education, research, and community benefit, the Permanente physicians continued to form bonds with academic institutions to learn, teach, and conduct research.

Sidney Garfield always put an emphasis on research and continuing education. Dr. Collen recalls: “When he (Garfield) set up the Department of Medical Methods Research (1961 in Northern California), he always maintained a close association with it. He always had important projects that he wanted our department to carry out because he was very self-critical of our organization. Although he was of course very proud of what he had conceived and accomplished, he always felt we should try to do better.”

Collen adds that having a robust research program helps attract good physicians to KP. “The best quality of care involves a simultaneous interest in teaching and research, in addition to patient care.”

Southern California pioneers had an eye on the quality ball

In Southern California, the physician group was also diligent in the selection of physicians from its beginnings in the early 1950s. Sam Sapin, quality pioneer, explains: “The SCPMG (Southern California Permanente Medical Group) had many intrinsic or built-in quality assurance mechanisms.”

These included: careful selection of physicians and imposing a probationary period of two to three years before election to partnership; and an informal but very effective form of physician peer review because of KP’s group practice model. Group practice also provided the opportunity for collaboration with colleagues and specialists to avoid inappropriate care and mistakes.

Sapin says other quality-ensuring factors included mandatory physician continuing education, ongoing sharing of inpatients and outpatients and their medical records as well as the accountability for quality of care vested in chiefs of service and medical directors who could withhold merit and longevity salary increases. Another key factor: there was no incentive for overutilization or performance of unnecessary procedures and no incentive to withhold appropriate care.

Henry Kaiser triggers a review of KP hospitals in 1959

Aside from the original and sincere intent to be the best in care, the Permanente physicians’ first stab at quality assurance came in 1959 when Henry Kaiser asked the question of Permanente health plan executive Clifford Keene, MD: “Do our hospitals provide quality of care? John Smillie, MD, an early KP San Francisco physician, recounts in his oral history: “Dr. Keene thought for a moment and he said, ‘I don’t know. I don’t know how we can judge how good the care is in our hospitals, but I’ll find out for you.’

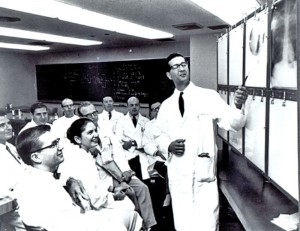

Emmett Lowrey, MD, leads a discussion among early Permanente physicians about the results of an X-ray examination.

“So Dr. Keene then commissioned Dorothea Daniels (KP’s first female hospital administrator) to do a study of hospital quality of care in all Kaiser Foundation Hospitals, not just Northern California, but in Southern California, and Oregon and Hawaii. She came back, I think in a year, with a very thorough report, which showed that in some hospitals the quality of care could be improved, and in other hospitals it was excellent. But it was a very honest and straightforward report,” Smillie said.

At that time, formal external quality assessment and documentation did not yet exist. The Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Hospitals had formed in 1952 and begun a voluntary accreditation program, but before the advent of Medicare in 1965 no government, employer or consumer influence had made itself felt in the regulation of medical care. That situation would soon change and the age of innocence for physician and hospital quality review was giving way to a much more complicated and anxious time.