Disabled Kaiser Permanente employee changed course of public transportation

In the 1960s, Harold Willson successfully advocated for the historically overlooked needs of people with disabilities on public transportation.

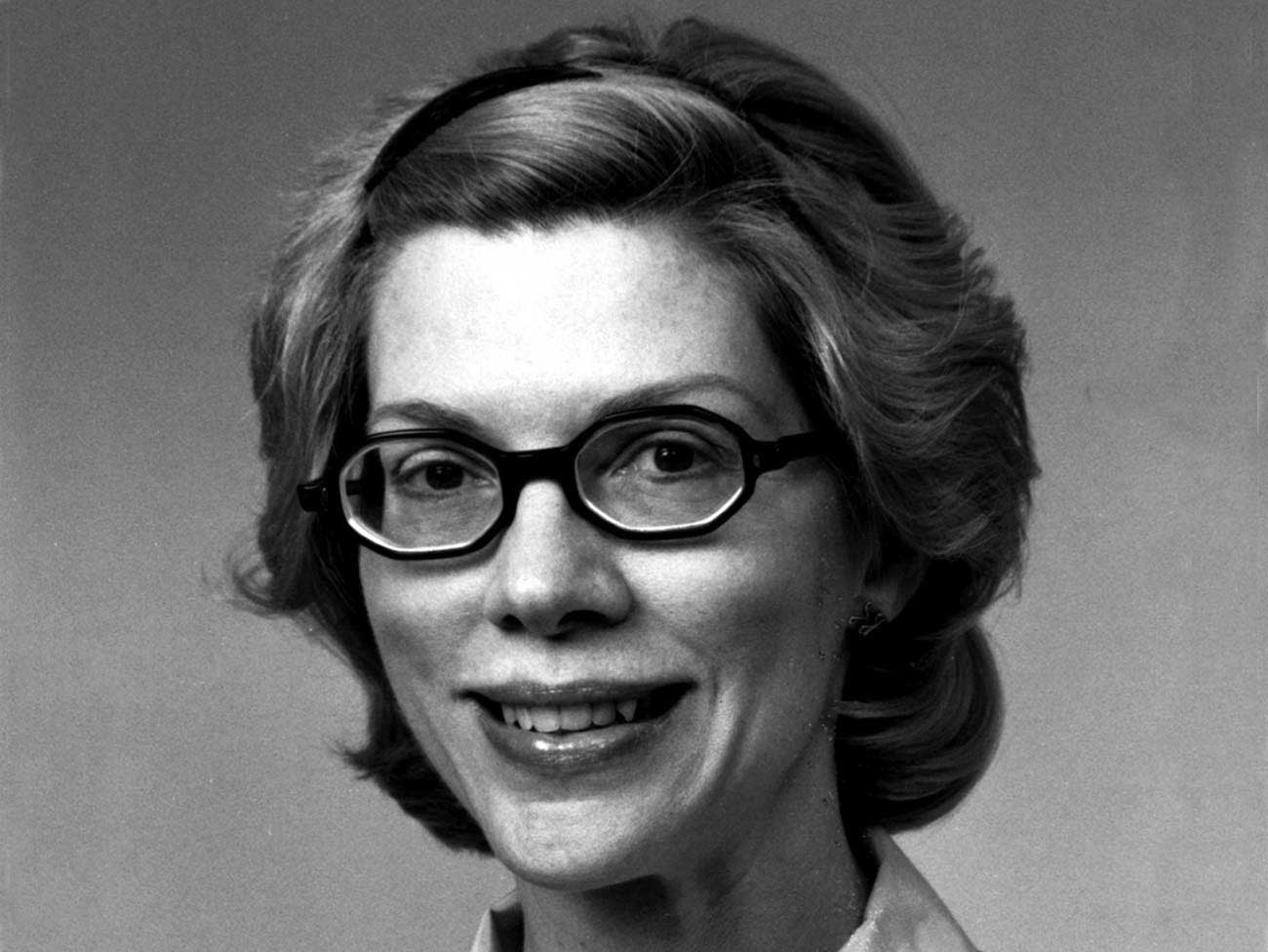

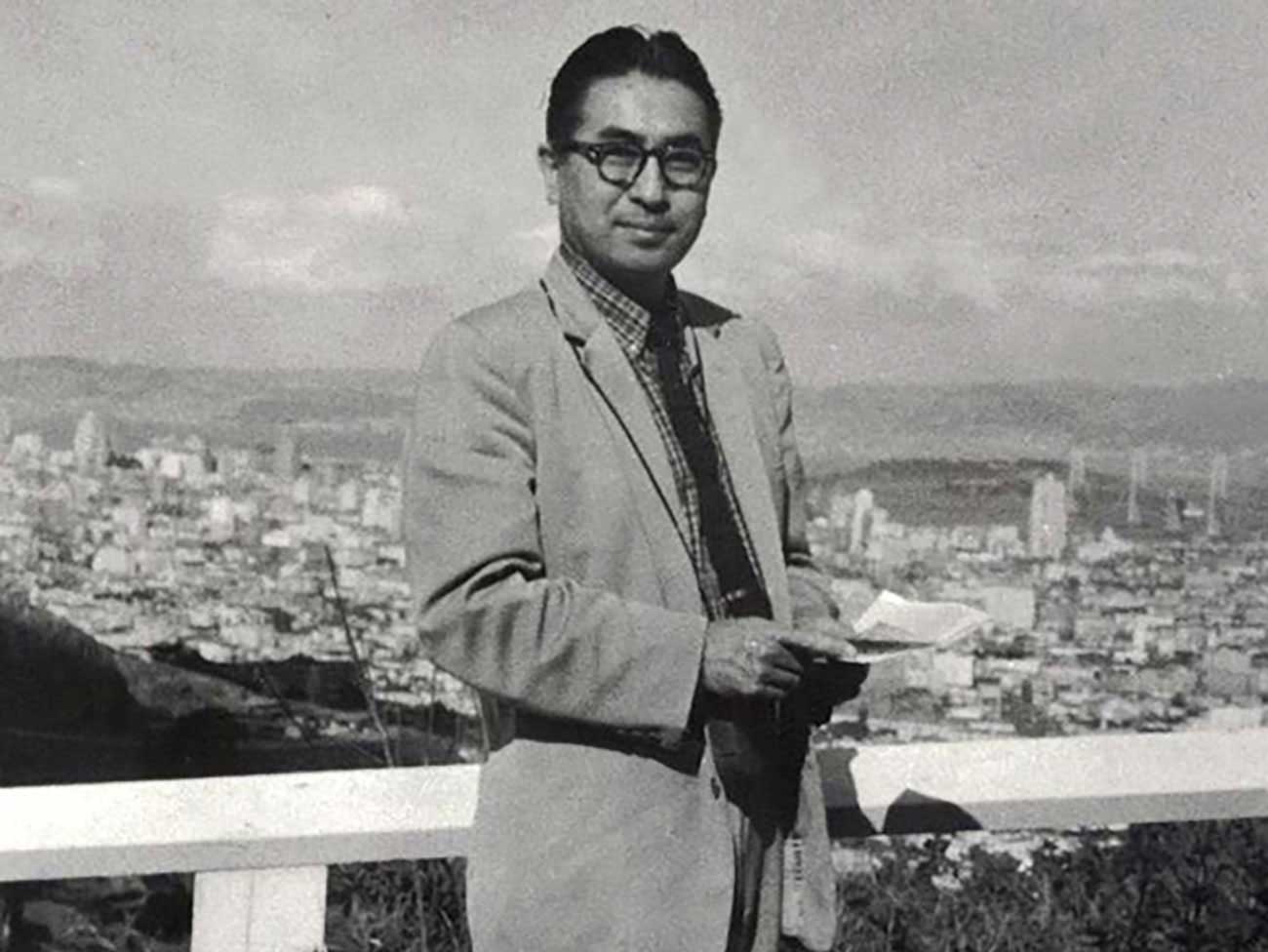

Harold Willson, Kaiser Permanente employee from 1957 to 1977, getting off a wheelchair-accessible BART train. Willson convinced officials to alter the system design to accommodate disabled passengers. Photo from Accent on Living magazine.

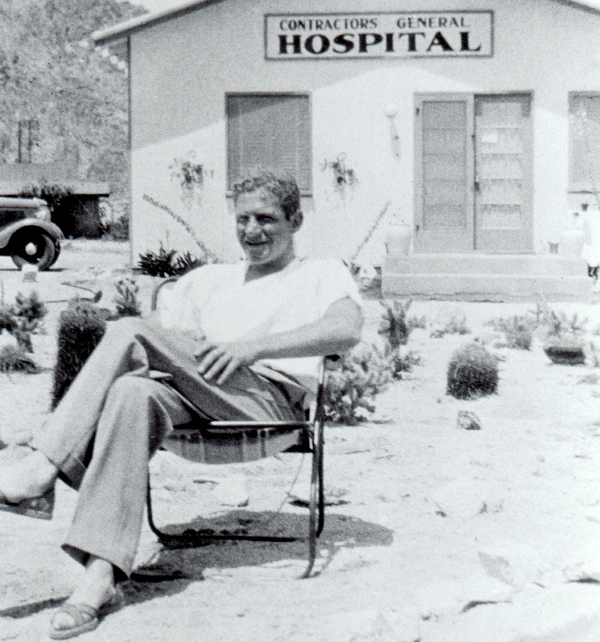

Kaiser Permanente’s embracing of diversity goes back to its beginnings in the World War II shipyards, and its ranks have included many disabled individuals who made significant contributions despite their handicaps. Harold T. Willson, a wheelchair-bound KP financial analyst, was one such person.

Willson, disabled in a 1948 mining accident, successfully lobbied leaders of the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District (BART) to make the high-speed train system accessible to the disabled.

BART, celebrating its 40th anniversary this year, was under construction in the early 1960s when Willson learned that the plans did not call for disabled access. He raised his objections and insisted on alterations.

Willson’s quiet persistence made BART leaders stop and listen. This relentlessness was characteristic of Willson’s approach to life. His story is one of triumph over tragedy.

A slate slide crushed a young miner

Willson was 21 years old when his entire life changed. The son of a mining engineer, he turned to mine work for income, as many young men do in West Virginia. His father had died two years earlier, and he was supporting the family and saving for college.

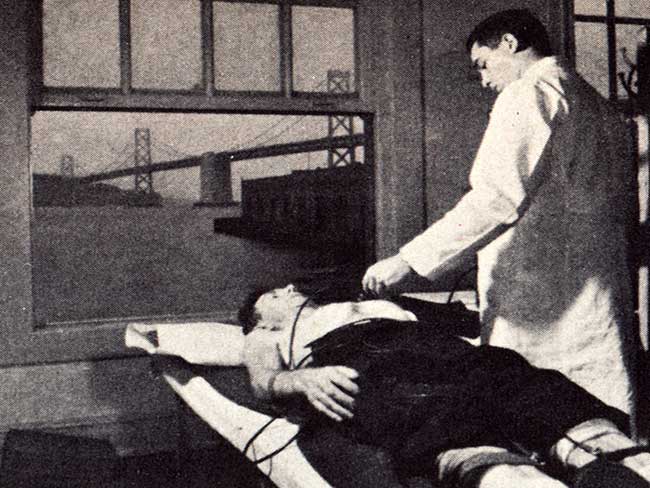

BART public phones were mounted lower to be convenient for passengers in wheelchairs. Photo from Accent on Living magazine.

He describes his last day of going down 500 feet to work at the mine owned by the New River Coal Company in Summerlee:

“On Friday, the 13th day of February 1948, I went to work the ‘hoot owl’ shift, and early the next morning just after my lunchtime, at 3:30 a.m., I was caught in a slate fall. I was badly crushed, ribs and back were broken with severe spinal damage.”

Willson was fortunate to be a member of Local 6048 of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA). Soon after his accident, he was sent to the Kabat-Kaiser Institute in Oakland, California, for rehabilitation (the facility was later located in Vallejo).

Kaiser rehabilitation center opened to miners

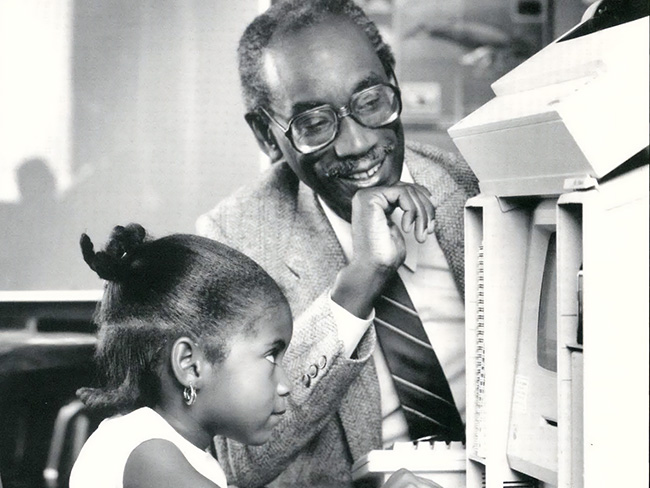

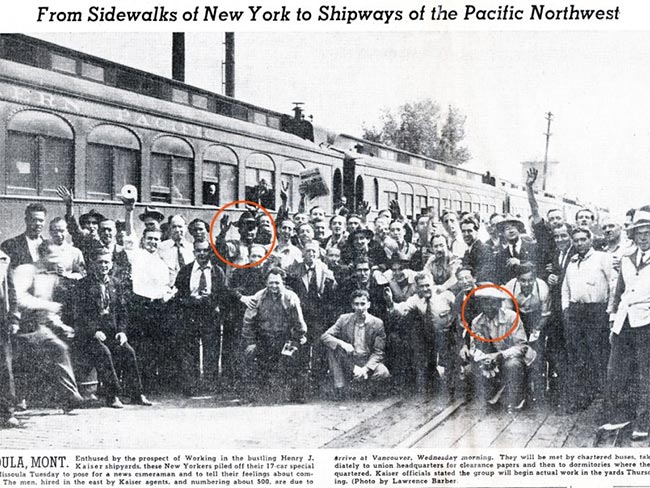

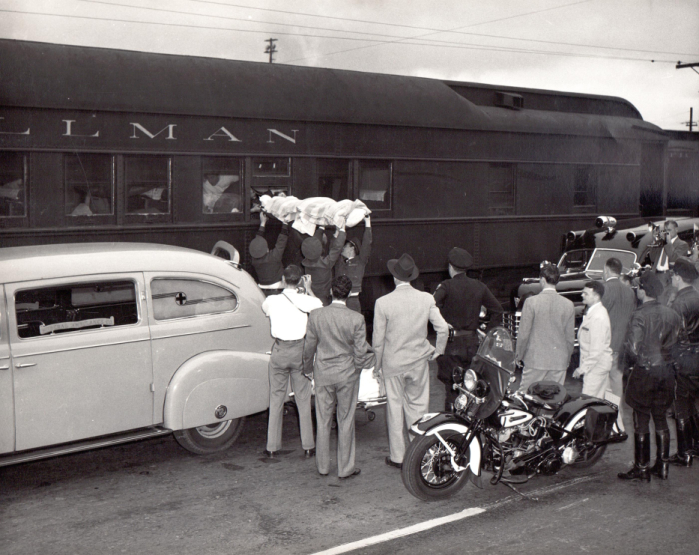

Just a few months earlier, legendary UMWA leader John L. Lewis and the UMWA Welfare and Retirement Fund had partnered with Henry J. Kaiser and the Kabat-Kaiser Institute to provide top-quality medical care and rehabilitation for injured miners.

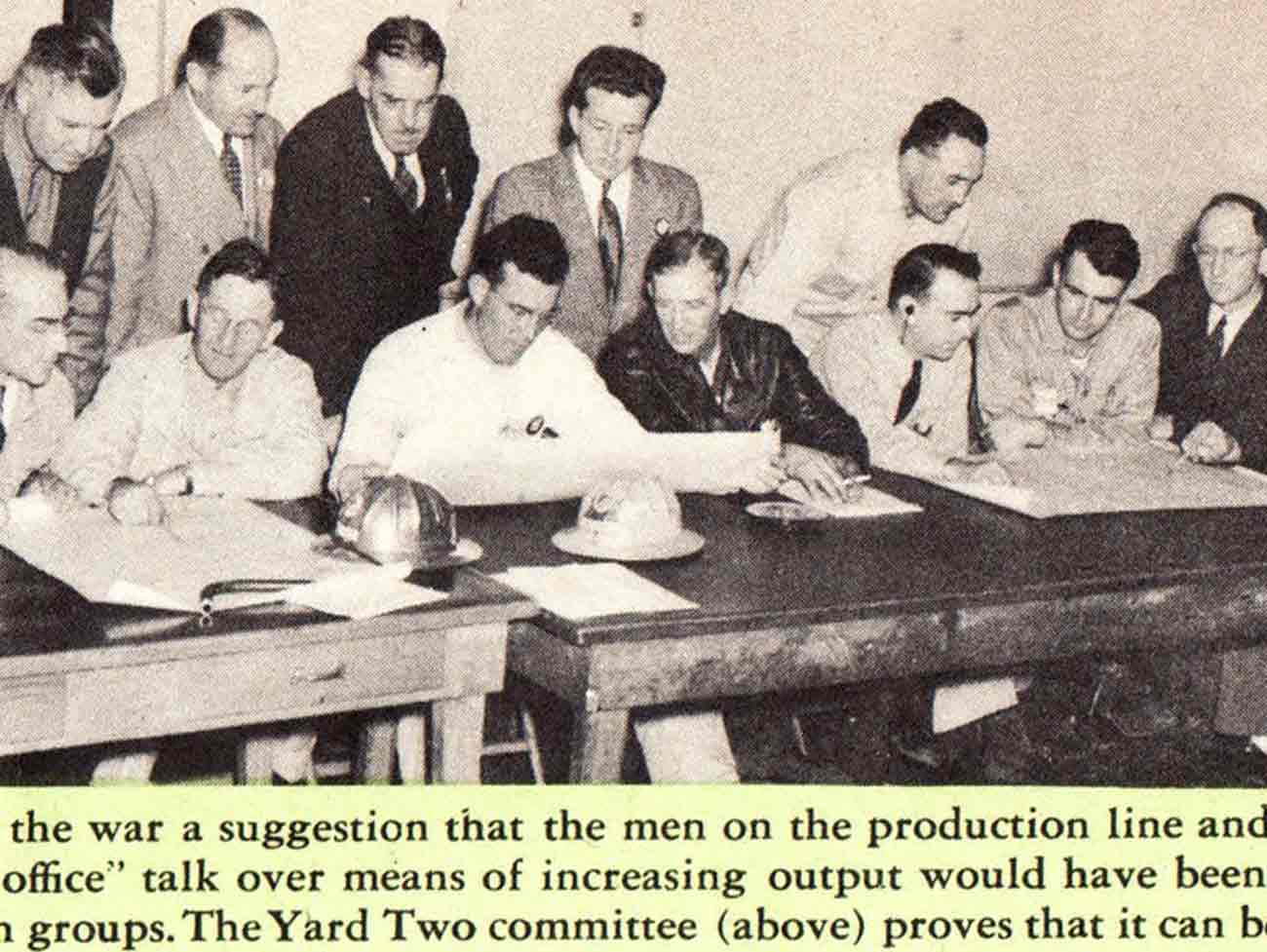

United Mine Workers of America patients arriving by Pullman train for Kaiser physical therapy, 1948.

Vocational institutions in the rural mining communities in the East were badly underfunded, and the California facilities offered a perfect venue for the union’s commitment to social welfare.

Willson was among the first group of miners to take the long trip west in three railroad cars, eventually followed by hundreds more. In an early instance of KP’s community benefit practices, the Permanente Health Plan continued to provide care even when the miners’ fund ran out of money.1

At Kabat-Kaiser Willson participated in physical therapy, played wheelchair basketball, and fell in love with his nurse and future wife. He got a job at the Bank of America, earned a bachelor of science in business administration, and then took a position as a senior financial analyst with the Kaiser Foundation Health Plan, retiring in 1977.

Willson put his persuasive powers to work

While employed by KP, Willson was a powerful advocate for urban design and construction that would accommodate disabled people. As a volunteer consultant to BART, he put in long hours over a 10-year period to ensure its accessibility for the disabled and elderly. He insisted that adequate transportation was often the deciding factor for disabled independence.

Special ticket gates were designed to allow wheelchairs to pass through. Photo from Accent on Living magazine.

BART Special ticket gates designed to allow wheelchairs to pass through

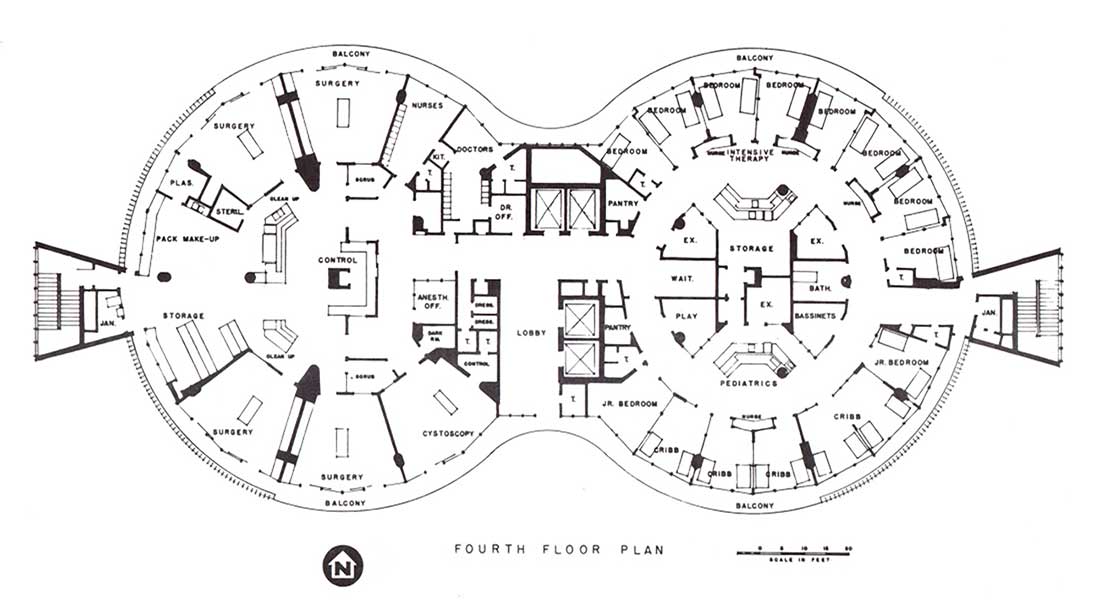

A feature article on his work in the 1973 issue of Accent on Living described it this way: “The original concept [of BART] in 1962 did not include the provisions for people with severely restricted mobility.

“At that time, Willson initiated a campaign to secure the present facilities, starting with endorsements from the elderly, the handicapped, and the general public. The project was not “sold” with fanfare and publicity but by person-to-person contact.”

A.E. Wolf, General Superintendent of Transportation for BART, was won over by Willson’s approach. He noted: “His suggestion was novel for rapid transit, no one had tried it; it posed all kinds of problems; cost was significant. Our staff, including myself, was hardly enthusiastic.

“But, he did not threaten, nor picket, nor sulk, nor lose patience. Instead, he was professional, pleasant, firm, and persistent. As a result, he won the support of each of our board members while maintaining a friendly relationship with our staff. This helped his cause immensely.”

Kaiser Permanente backed Willson’s advocacy

In keeping with its policy to support efforts to improve opportunities for the disabled, as well as other minority groups, Kaiser Permanente gave Willson the freedom to pursue his accessibility campaign.

“It is appropriate here to commend Kaiser [Permanente leaders] ... because of their interest, encouragement, and public service philosophy,” Wolf also noted. “The willingness to arrange time for an employee to participate in this community project was necessary for its success.”2

Willson agreed: “ ... Since our Medical Care Program is one of the largest providers of health services ... we should assume the leadership role in promoting and participating in activities and programs that will create a barrier-free environment for the handicapped and elderly.”

Willson’s specific recommendations included large elevators at every stop, accessible restrooms, wide parking spaces, narrow gaps between trains and platforms, and loudspeaker announcements.

His broader vision was perhaps best articulated in a statement he made before the American Public Transportation Association in 1976: “We must exert every effort to ... create a barrier-free transportation environment for those that are handicapped and for the non-handicapped destined to become disabled such as yourselves.”

1 The charitable nature of this relationship is described in A Model for National Health Care by Rickey Hendricks: “When the union fund suffered a financial setback in late 1949, the Permanente Hospital Foundation continued to transport and care for miners at Permanente expense. Kabat-Kaiser continued through 1952 to run on a deficit of almost $100,000.”

2 Comments by A.E. Wolf, General Superintendent of Transportation, Bay Area Rapid Transit District, to Workshop number 3, Transportation Environment, 1972 National Easter Seal Convention, Chicago, Illinois, November 9, 1972.