Henry Kaiser's racial acceptance began with one of first employees

James A. Shaw introduced Henry J. and Edgar Kaiser early to the diversity of people and the value of building relationships with each other.

“Tote! Tote!”

Edgar Kaiser, age 5, would call out to a gregarious Black laborer named James A. Shaw with those words.

Jimmy Shaw would hoist the lad up onto his shoulders and carry the boy, all the while raking asphalt on a road-building project for Edgar’s father, Henry J. Kaiser.

The year was 1913. The site was a work camp where the toddler would often live, sleeping in a car or a tent, with his parents, Henry and Bess Kaiser. Little Edgar’s affection for riding on Shaw’s shoulders, calling out “Tote, Tote!” when he’d see Shaw, earned Jimmy the nickname “Tote,” or sometimes “Totem,” for the rest of his life.

This was in the early years of Henry Kaiser’s fledgling road-building business — long before he became the great 20th-century industrialist who gained fame building highways, dams, and World War II ships.

And Totem Shaw’s story, as recorded in historic archives, helps shed light on both Henry and Edgar Kaiser’s later reputations as businessmen who understood the value of workforce diversity and, in their personal lives, moved beyond racial divides decades before the rest of the country.

"Totem" Shaw is seen in an undated photograph after his retirement in Fontana, Calif. (Photo courtesy of John Charles Anicic Jr., author of "Images of America: Kaiser Steel Fontana," Acadia Publishing, 2006.)

Born in 1879, Shaw was not quite 2 years older than Henry J. and represents the earliest documented friendship between the Kaisers and a person of African heritage. Shaw’s is a powerful story that helps explain why Henry Kaiser was open to hiring minority workers.

Shaw was Kaiser’s first Black employee, hired several years before Kaiser even formed his own company. He actually was hired by A. B. Ordway, Kaiser’s very first employee, when they were working for another company paving part of Post Street in Spokane, Wash., about 1909. Kaiser was general superintendent and Ordway was foreman.

One day Shaw walked up to the Post Street paving gang and asked Ordway for a job. According to Gordon Barteau, a Portland Oregonian newspaper reporter who wrote a profile of Shaw in 1943, “Ordway sized Tote up and said he thought Tote looked kind of runty for a job like that.”

In a style reminiscent of Kaiser himself, Shaw offered to work for free for a week on trial.

“Well … the first day he wore out two men and the next day Ordway told him he was on the payroll,” the Oregonian reported.

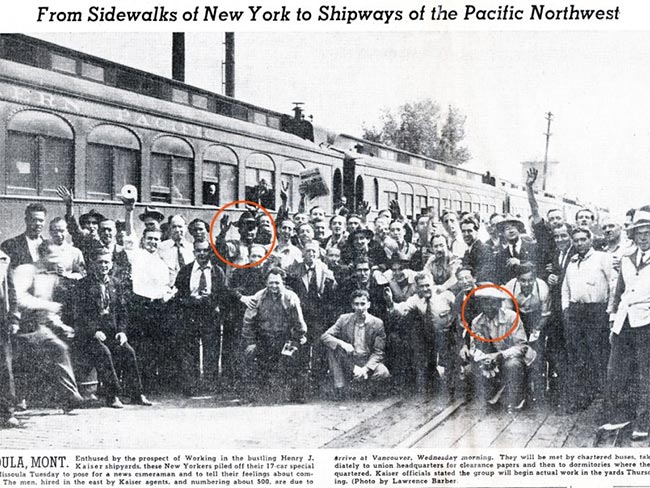

“Tote” worked in a variety of jobs on just about every big Kaiser project — from road building in Cuba to the Grand Coulee Dam, the Vancouver Shipyards in World War II, and the Kaiser steel mill in Fontana, Calif., before he retired. It was during the war years in Vancouver, according to Barteau’s article, that whenever Henry Kaiser “comes to town he always looks up Tote and they hash over the old days.”

Clearly, it was Shaw’s relationship with Edgar and his ability as a skilled laborer with problem-solving skills that made him a lifelong, unforgettable friend of Henry Kaiser.

During construction of the original Highway 99 between Redding and Red Bluff in Northern California, in 1921, Kaiser was having trouble keeping a muddy detour open. He’d sent in a work crew of six men, and they had failed.

Kaiser summoned Shaw. “Tote,” he said, “every truck on the job is stuck in the mud. …You go down there and see what you can do.”

Shaw grabbed an ax, a pick, and a shovel. In short order, he had all of the trucks out of the mud and running.

“How did you do it?” Kaiser asked him.

“Mr. Kaiser,” he replied, “when you do things, you mixes brains and money. Well, sir, I mixes mud and brains.”

“Kaiser loved the phrase,” wrote one of his biographers, Mark Foster. “It became a company slogan.”

Shaw lived his final years in Fontana. They had a big party for him when turned 85 in 1964. In addition to cards, gifts, and a huge birthday cake, a teletype arrived from the giant Kaiser Industries headquarters in Oakland — birthday greetings from A. B. Ordway, who had known “Tote” since the day he had walked up to Ordway on Post Street in Spokane and asked for a job.

-

Social Share

- Share Henry Kaiser's Racial Acceptance Began With one of First Employees on Pinterest

- Share Henry Kaiser's Racial Acceptance Began With one of First Employees on LinkedIn

- Share Henry Kaiser's Racial Acceptance Began With one of First Employees on Twitter

- Share Henry Kaiser's Racial Acceptance Began With one of First Employees on Facebook

- Print Henry Kaiser's Racial Acceptance Began With one of First Employees

- Email Henry Kaiser's Racial Acceptance Began With one of First Employees

July 16, 2025

More than just a game

Kaiser Permanente partners with Special Olympics of Southern California …

April 30, 2025

A history of trailblazing nurses

Nursing pioneers lay the foundation for the future of Kaiser Permanente …

April 16, 2025

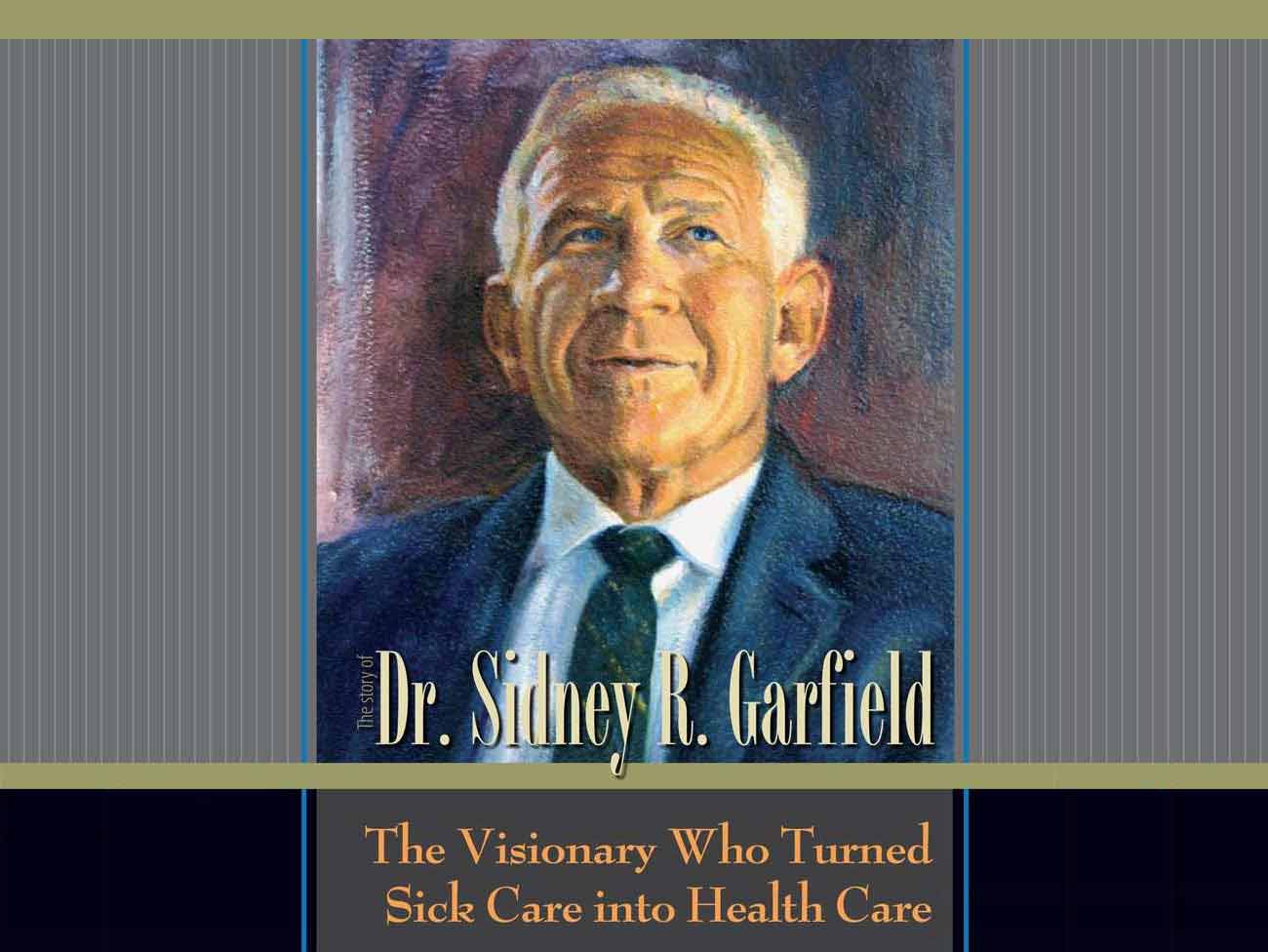

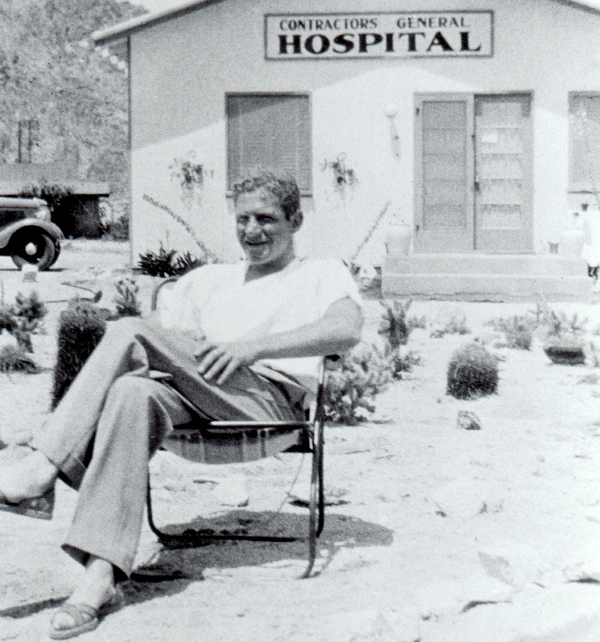

Sidney R. Garfield, MD: Pioneer of modern health care

Kaiser Permanente’s co-founding physician spread prepaid care and the idea …

March 17, 2025

Remembering Bill Coggins and his lasting legacy

The founder of the Kaiser Permanente Watts Counseling and Learning Center …

December 16, 2024

Helping to build and support inclusive communities

At the Special Olympics Southern California Fall Games, Kaiser Permanente …

November 6, 2024

A best place to work for veterans

As a 2024 top Military Friendly Employer, Kaiser Permanente supports veterans …

October 2, 2024

Honored for supporting people with disabilities

Leading U.S. disability organizations recognize Kaiser Permanente for supporting …

September 16, 2024

Voting affects the health of our communities

In honor of National Voter Registration Day, we encourage everyone who …

July 16, 2024

Teacher residency program improves retention and diversity

A $1.5 million Kaiser Permanente grant addresses Colorado teacher shortage …

July 2, 2024

Reducing cultural barriers to food security

To reduce barriers, Food Bank of the Rockies’ Culturally Responsive Food …

June 19, 2024

Investments in Black community promote total health for all

Funding from Kaiser Permanente in Washington helps to promote mental health, …

May 30, 2024

Special Olympics Summer Games: Will you play a part?

Kaiser Permanente employee Carrie Zaragoza volunteers for Special Olympics …

May 14, 2024

Recognized again for leadership in diversity and inclusion

Fair360 names Kaiser Permanente to its Top 50 Hall of Fame for the seventh …

May 3, 2024

Henry J. Kaiser: America’s health care visionary

Kaiser was a major figure in the construction, engineering, and shipbuilding …

April 8, 2024

Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream is alive at Kaiser Permanente

Greg A. Adams, chair and chief executive officer of Kaiser Permanente, …

March 6, 2024

Former employee honored for supporting South LA families

Bill Coggins, who founded the Kaiser Permanente Watts Counseling and Learning …

March 4, 2024

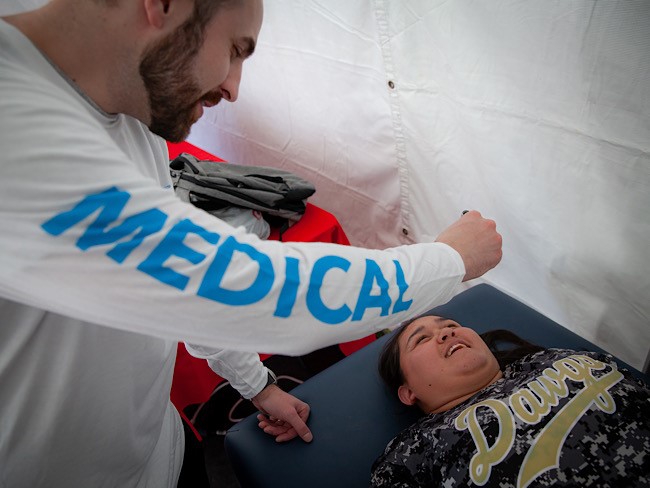

Taking care of Special Olympics athletes

Kaiser Permanente physicians and medical students provide medical exams …

February 13, 2024

A legacy of life-changing community support and partnership

The Kaiser Permanente Watts Counseling and Learning Center started as a …

February 2, 2024

Expanding medical, social, and educational services in Watts

Kaiser Permanente opens medical offices and a new home for the Watts Counseling …

December 20, 2023

Championing inclusivity at the Fall Games

Kaiser Permanente celebrates inclusion at Special Olympics Southern California …

November 1, 2023

Meet our 2023 to 2024 public health fellows

To help develop talented, diverse community leaders, Kaiser Permanente …

October 17, 2023

How Kaiser Permanente evolved

Sidney R. Garfield, MD, and Henry J. Kaiser came together to pioneer an …

September 13, 2023

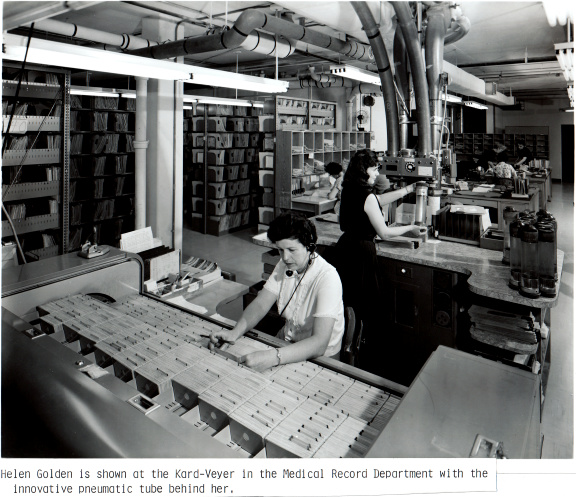

Transforming the medical record

Kaiser Permanente’s adoption of disruptive technology in the 1970s sparked …

August 1, 2023

Joining forces to improve community health

The Kaiser Permanente and 211 LA partnership makes strides in improving …

June 30, 2023

Our response to Supreme Court ruling on LGBTQIA+ protections

Kaiser Permanente addresses the Supreme Court decision on LGBTQIA+ protections …

June 29, 2023

Our response to Supreme Court's ruling on affirmative action

Kaiser Permanente addresses the Supreme Court decision on affirmative action …

June 29, 2023

Special Olympics athletes go for the gold

Kaiser Permanente celebrated its sixth year as official health partner …

June 20, 2023

Helping entrepreneurs in under-resourced communities

Kaiser Permanente's support of Inner City Capital Connections program helps …

June 14, 2023

Honored for commitment to people with disabilities

The Achievable Foundation recognized Kaiser Permanente for its work to …

May 10, 2023

A workplace for all

We value and respect employees and physicians of all backgrounds, identities, …

May 10, 2023

Equity, inclusion, and diversity

We strive for equity and inclusion for all.

May 2, 2023

Women lead an industrial revolution at the Kaiser Shipyards

Early women workers at the Kaiser shipyards diversified home front World …

April 27, 2023

Inspiring students to pursue health care careers

Kaiser Permanente is confronting future health care staffing challenges …

April 25, 2023

Hannah Peters, MD, provides essential care to ‘Rosies’

When thousands of women industrial workers, often called “Rosies,” joined …

November 14, 2022

It’s time to rethink health care quality measurement

To meaningfully improve health equity, we must shift our focus to outcomes …

November 11, 2022

A history of leading the way

For over 75 innovative years, we have delivered high-quality and affordable …

November 11, 2022

Early leaders in equity and inclusion

Explore Kaiser Permanente’s commitment to equitable, culturally responsive …

November 11, 2022

Pioneers and groundbreakers

Learn about the trailblazers from Kaiser Permanente who shaped our legacy …

November 11, 2022

Our integrated care model

We’re different than other health plans, and that’s how we think health …

November 11, 2022

Our history

Kaiser Permanente’s groundbreaking integrated care model has evolved through …

October 14, 2022

Contact Heritage Resources

October 1, 2022

Innovation and research

Learn about our rich legacy of scientific research that spurred revolutionary …

July 29, 2022

Health care workforce

Strengthening America’s health care workforce

May 26, 2022

Nurse practitioners: Historical advances in nursing

A doctor shortage in the late 1960s and an innovative partnership helped …

February 21, 2022

A best place to work for LGBTQ+ equality

Human Rights Campaign Foundation gives Kaiser Permanente another perfect …

December 6, 2021

Faith leaders use trusted voices to encourage vaccination

Grants expand support for faith-based organizations working to protect …

September 10, 2021

‘Baby in the drawer’ helped turn the tide for breastfeeding

This innovation in rooming-in allowed newborns to stay close to mothers …

August 25, 2021

Kaiser Permanente’s history of nondiscrimination

Our principles of diversity and our inclusive care began during World War …

July 22, 2021

A long history of equity for workers with disabilities

In Henry J. Kaiser’s shipyards, workers were judged by their abilities, …

July 7, 2021

Achieving health equity

Equal medical care is not enough to end disparities in health outcomes.

June 2, 2021

Path to employment: Black workers in Kaiser shipyards

Kaiser Permanente, Henry J. Kaiser’s sole remaining institutional legacy, …

March 23, 2021

Vaccine Equity Toolkit will help address equitable access

As vaccines bring hope to end the pandemic, Kaiser Permanente’s toolkit …

February 22, 2021

The Permanente Richmond Field Hospital

Forlorn and all but forgotten, it played a proud role during the World …

September 28, 2020

A legacy of disruptive innovation

Proceeds from a new book detailing the history of the Kaiser Foundation …

August 26, 2020

Kaiser Permanente’s pioneering nurse-midwives

The 1970s nurse-midwife movement transformed delivery practices.

July 30, 2020

Books and publications about our history

Interested in learning more about the history of Kaiser Permanente and …

May 18, 2020

Nurses step up in crises

Kaiser Permanente nurses have been saving lives on the front lines since …

November 8, 2019

Swords into stethoscopes — veterans in health professions

Kaiser Permanente has actively hired veterans in all capacities since World …

August 28, 2019

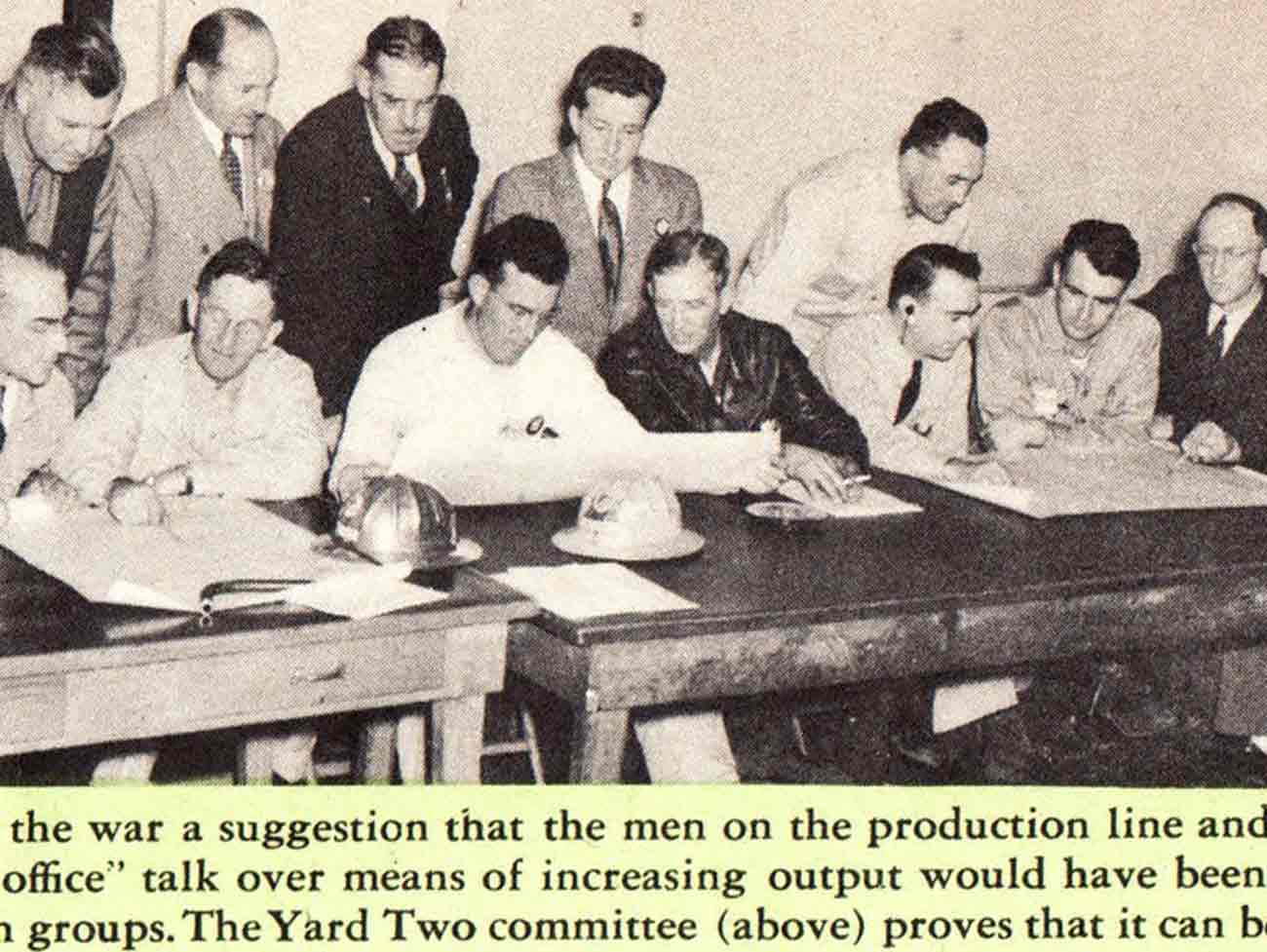

When labor and management work side by side

From war-era labor-management committees to today’s unit-based teams, cooperation …

August 2, 2019

Thriving with 1960s-launched KFOG radio

Kaiser Broadcasting radio connected listeners, while TV stations brought …

June 5, 2019

Breaking LGBT barriers for Kaiser Permanente employees

“We managed to ultimately break through that barrier.” — Kaiser Permanente …

March 29, 2019

Equal pay for equal work

Kaiser shipyards in Oregon hired the first 2 female welders at equal pay …

February 5, 2019

Mobile clinics: 'Health on wheels'

Kaiser Permanente mobile health vehicles brought care to people, closing …

December 10, 2018

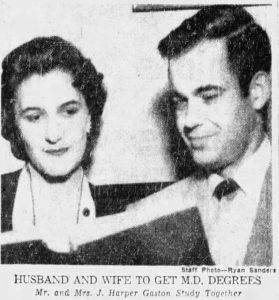

Southern comfort — Dr. Gaston and The Southeast Permanente Medical Group

Local Atlanta physicians built community relationships to start Kaiser …

May 30, 2018

John Graham Smillie, MD, pediatrician and innovator

Celebrating the life of a pioneering pediatrician who inspired the baby …

April 30, 2018

Nursing pioneers leads to a legacy of leadership

Kaiser Foundation School of Nursing students learned a new philosophy emphasizing …

April 19, 2018

Wasting nothing: Recycling then and now

Environmentalism was a common practice at the Kaiser shipyards long before …

April 12, 2018

Harold Hatch, health insurance visionary

The founding of Kaiser Permanente's concept of prepaid health care in the …

March 26, 2018

5 physicians who made a difference

Meet 5 outstanding doctors who advanced the practice of medical care with …

March 13, 2018

Henry J. Kaiser and the new economics of medical care

Kaiser Permanente’s co-founder talks about the importance of building hospitals …

March 8, 2018

Slacks, not slackers — women’s role in winning World War II

Women who worked in the Kaiser shipyards helped lay the groundwork for …

February 22, 2018

The amazing true story of Park Ranger Betty Reid Soskin

She is the oldest national park ranger in the country with a legacy of …

December 19, 2017

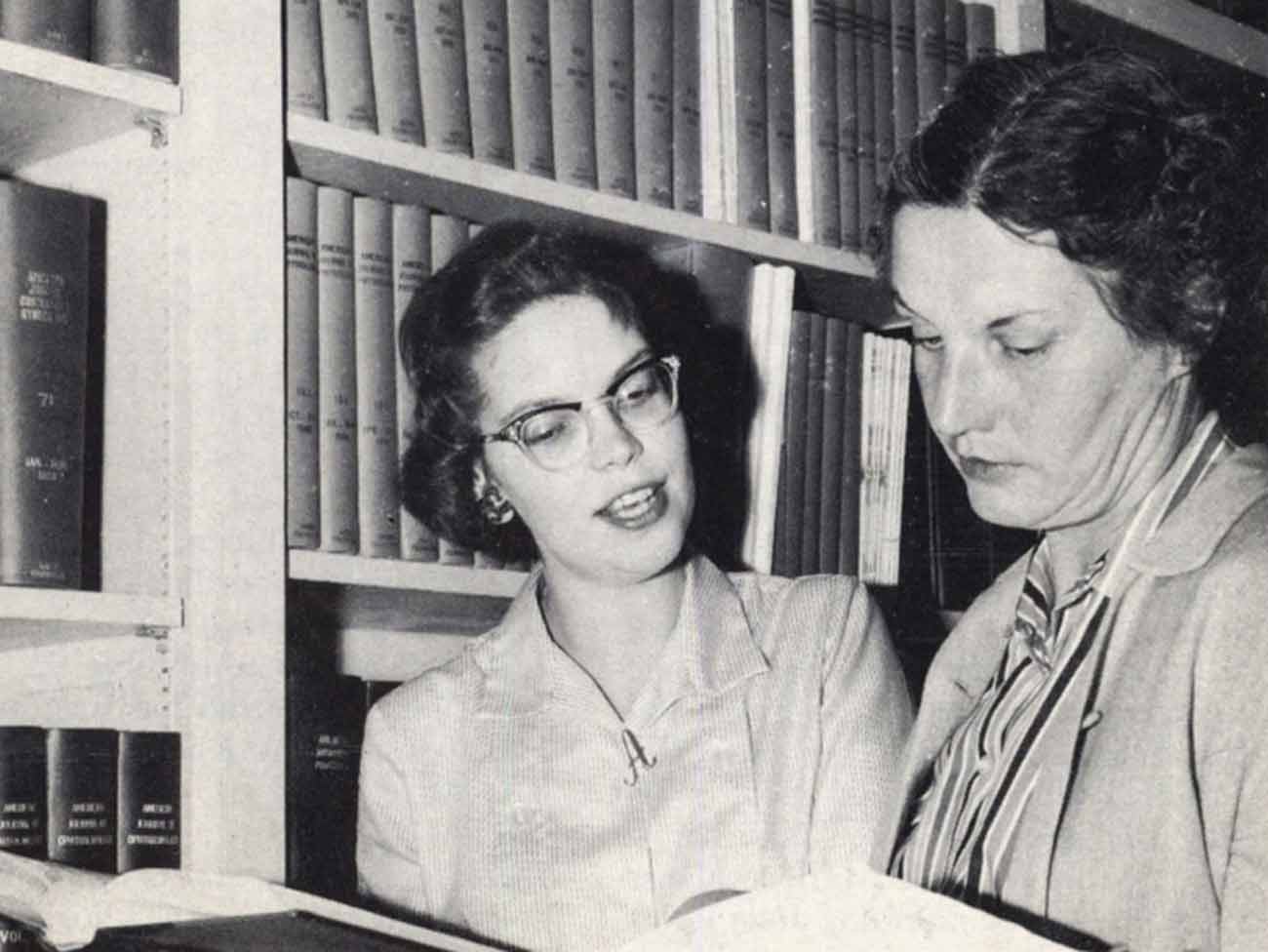

From boats to books: A history of Kaiser Permanente’s medical libraries

Kaiser Permanente librarians are vital in helping clinicians remain updated …

November 7, 2017

Patriot in pinstripes: Honoring veterans, home front, and peace

Henry J. Kaiser's commitment to the diverse workforce on the home front …

October 12, 2017

An experiment named Fabiola

Health care takes root in Oakland, California.

September 29, 2017

Harbor City Hospital: Beachhead for labor health care

The story of Kaiser Permanente's South Bay Medical Center finds its roots …

August 15, 2017

Sidney R. Garfield, MD, on medical care as a right

Hear Kaiser Permanente’s physician co-founder talk about what he learned …

August 10, 2017

‘Good medicine brought within reach of all'

Paul de Kruif, microbiologist and writer, provides early accounts of Kaiser …

July 14, 2017

Kaiser’s role in building an accessible transit system

Harold Willson, an employee, and an advocate for accessible transportation, …

July 7, 2017

Mending bodies and minds — Kabat-Kaiser Vallejo

The expanded new location provided care to a greater population of members …

June 23, 2017

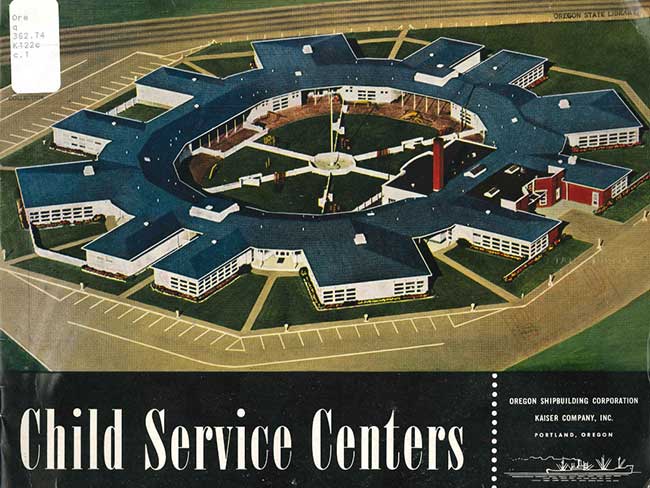

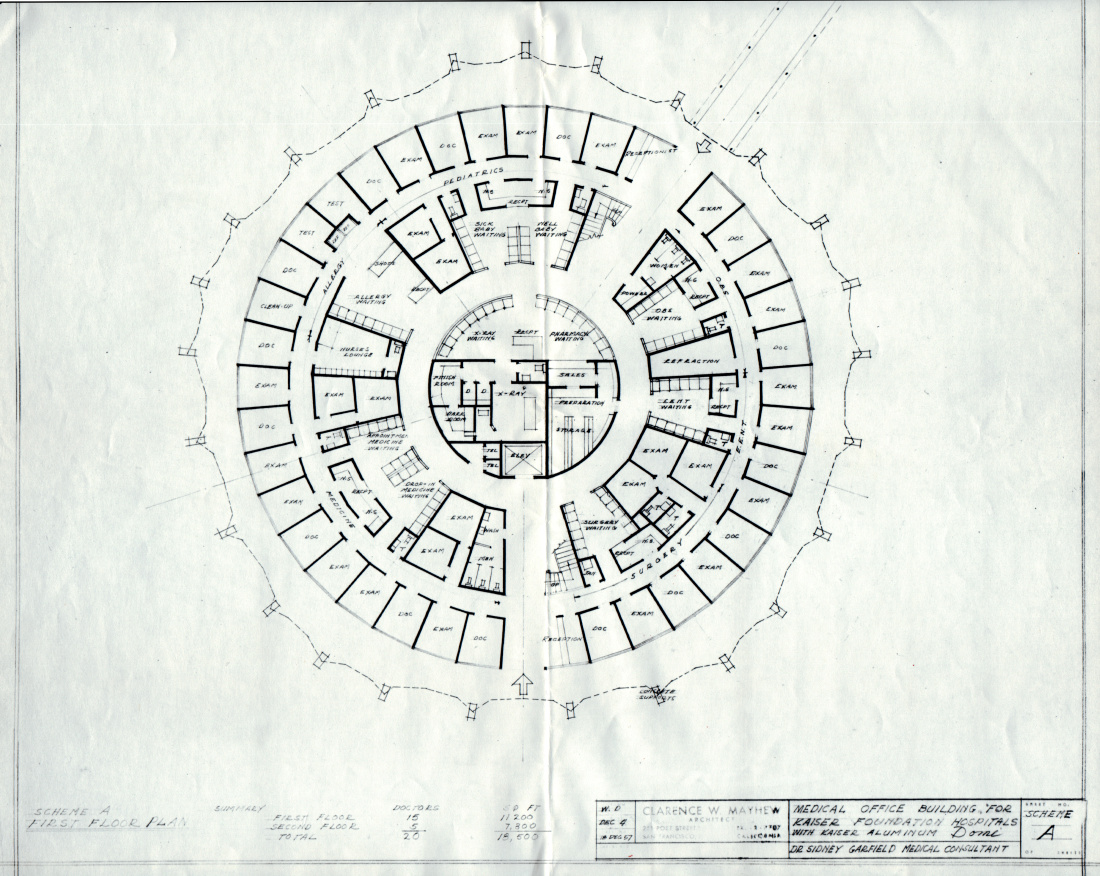

No getting round it: An innovative approach to building design

Kaiser Permanente incorporated innovative circular architectural designs …

June 14, 2017

Kabat-Kaiser: Improving quality of life through rehabilitation

When polio epidemics erupted, pioneering treatments by Dr. Herman Kabat …

June 9, 2017

Edmund (Ted) Van Brunt, pioneer of electronic health records, dies at age …

Throughout his career, Dr. Van Brunt applied computers and databases in …

May 4, 2017

How a Kaiser Permanente nurse transformed health education

Kaiser Permanente's Health Education Research Center and Health Education …

March 22, 2017

Kaiser Permanente and Group Health Cooperative: Working together since …

The formation of Kaiser Permanente Washington comes from longstanding collaboration, …

March 7, 2017

Beatrice Lei, MD: From Shantou, China, to Richmond, California

She served as a role model and inspiration to the women physicians and …

March 1, 2017

Screening for better health: Medical care as a right

When industrial workers joined the health plan, an integrated battery of …

February 17, 2017

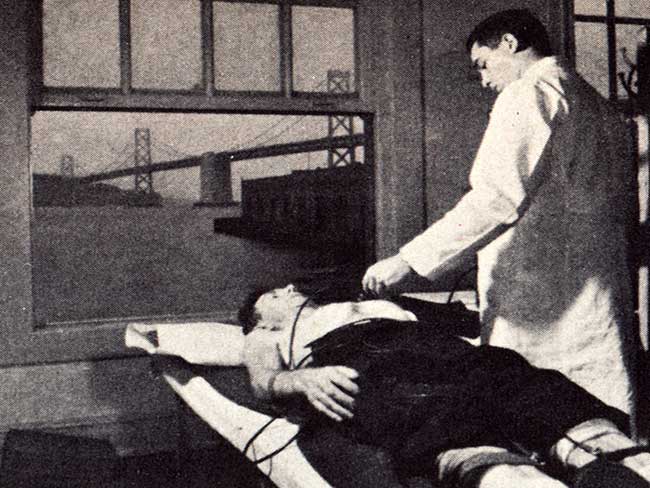

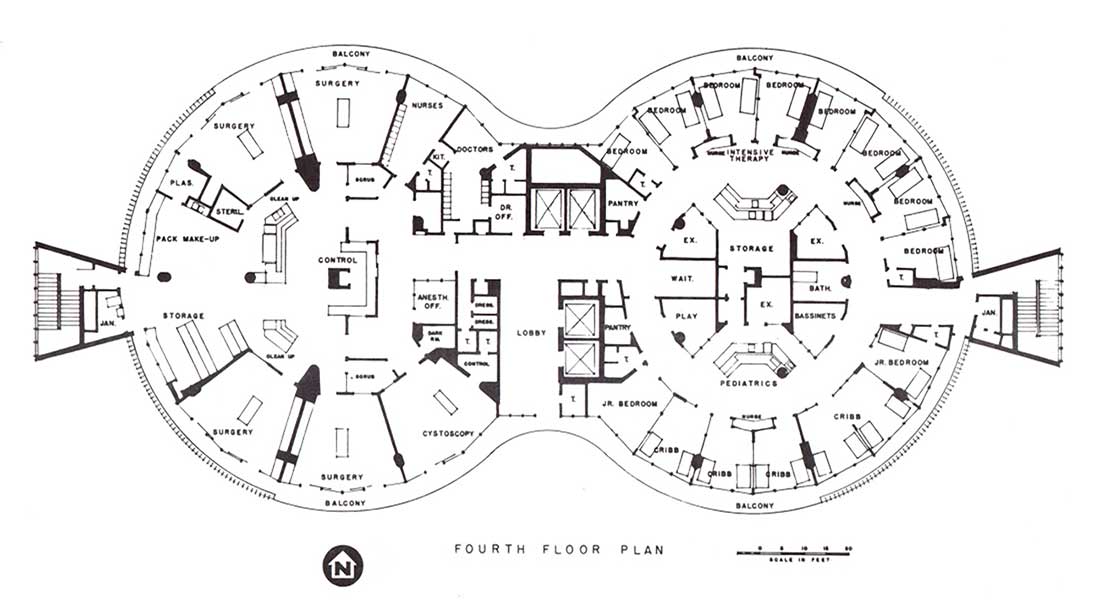

Experiments in radial hospital design

The 1960s represented a bold step in medical office architecture around …

February 3, 2017

Ellamae Simmons — trailblazing African American physician

Ellamae Simmons, MD, worked at Kaiser Permanente for 25 years, and to this …

January 27, 2017

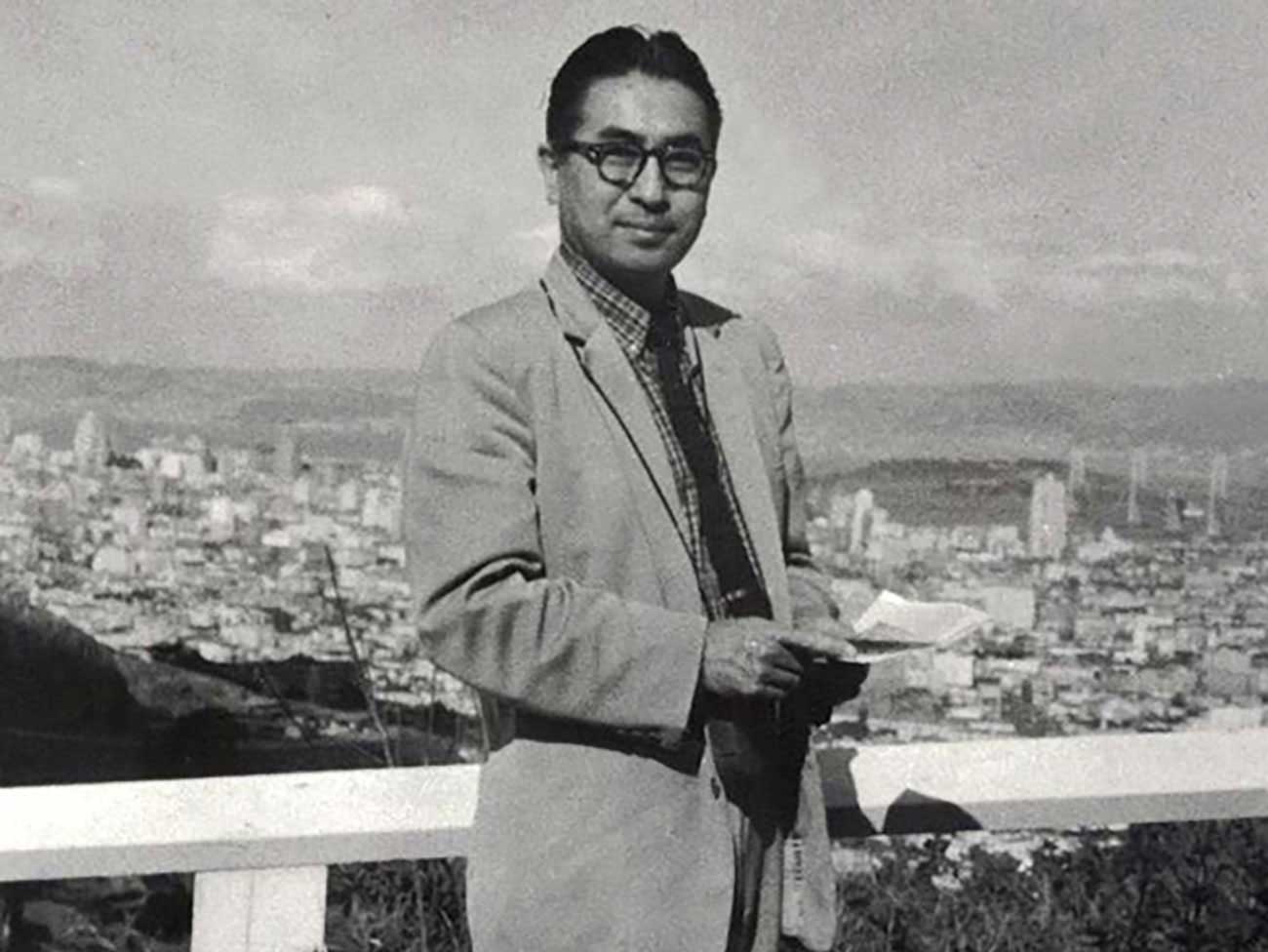

Japanese-American doctors overcame internment setbacks

Despite restrictive hiring practices after World War II, Kaiser Permanente …

November 16, 2016

Betty Reid Soskin honored with lifetime achievement award

The California Studies Association presents the Carey McWilliams Award …

October 17, 2016

Kaiser Motors in Oakland — “We sell to make friends.”

In 1946 Henry J. Kaiser Motors purchased half a square block in downtown …

October 12, 2016

Kaiser’s geodesic dome clinic

There are hospital rounds, and there are round hospitals.

May 5, 2016

Male nursing pioneers

Groundbreaking male students diversify the Kaiser Foundation School of …

April 20, 2016

Henry J. Kaiser’s environmental stewardship

Since the 1940s, Kaiser Industries and Kaiser Permanente have a long history …

November 13, 2015

Dr. Morris Collen’s last book on medical informatics

The last published work of Morris F. Collen, MD, one of Kaiser Permanente’s …

October 29, 2015

From paper to pixels — the new paradigm of electronic medical records

Transitioning to electronic health records introduced new approaches, skills, …

September 23, 2015

Kaiser Permanente and NASA — taking telemedicine out of this world

Kaiser Permanente International designs, develop, and test a remote health …

July 22, 2015

Kaiser Permanente as a national model for care

Kaiser Permanente proposed a revolutionary national health care model after …

July 21, 2015

Kaiser Permanente's early support from labor

Experiencing the Kaiser Permanente health plan led labor unions to support …