Wartime shipyard child care centers set standards for future

In 1943, Henry J. Kaiser invited key figures in child development studies to his shipyards to set up facilities and programs so workers could build ships without worrying about their children.

Nap time for Kaiser kids.

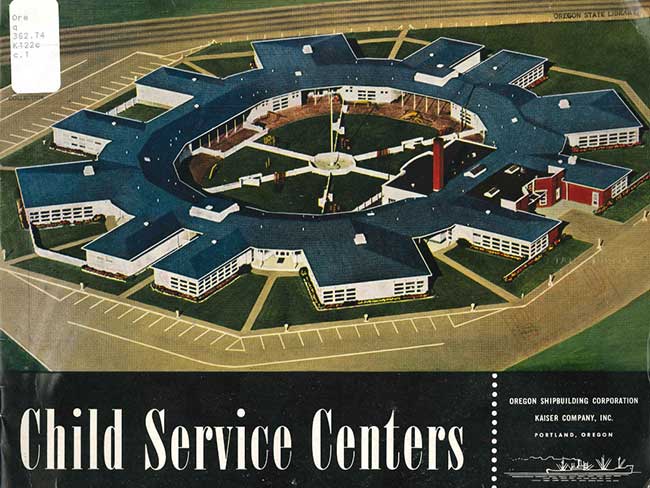

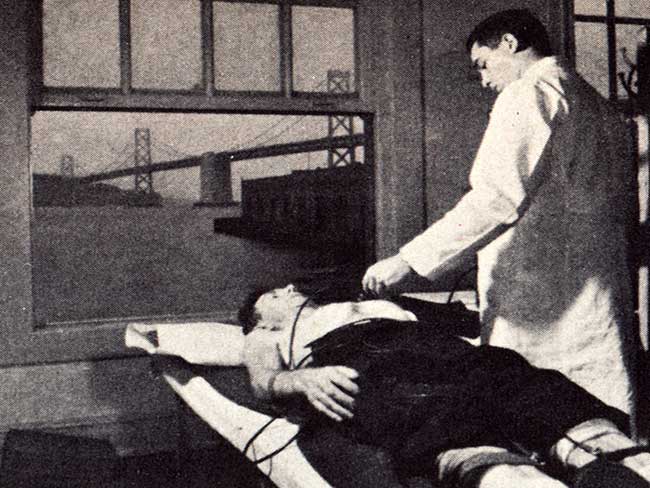

Child care at the workplace was a brand new phenomenon in World War II. The government-subsidized Kaiser West Coast Shipyards nursery schools, which enrolled more than 7,000 offspring of women war workers, offered the perfect opportunity to test theories of the then-fledgling field of child development.

In 1943, Henry J. Kaiser invited key figures in child development studies to his shipyards to set up ideal facilities and programs so workers could build ships without worrying about the safety and health of their children. These model child care centers at the Kaiser shipyards in Richmond, California, and Portland, Oregon, yielded valuable research results that helped fuel the study of early childhood education for decades after the war.

Catherine Landreth, PhD, of the University of California, Berkeley, set up the Richmond schools program. Lois Meek Stolz, PhD, a child development researcher and author from Columbia University and UC Berkeley, set up the Portland centers. James L. Hymes, Jr., a student of Stolz at Columbia, served as manager of the Portland centers.

Stolz and Landreth continued to exert influence on the child development world until the end of their lives. But it was Hymes, just 30 at war’s end, who would become a prodigious contributor to the child development literature for the next 5 decades. His work is often quoted today. One such quote reflects lessons from the home front: “Every day-care center, whether it knows it or not, is a school. The choice is never between custodial care and education. The choice is between unplanned and planned education, between conscious and unconscious education, between bad education and good education.”

Early Hymes work discovered

Recently, my colleagues and I unearthed the final report of the 2 Portland Kaiser wartime child development centers, along with a series of 7 pamphlets written for postwar child care providers. We found these documents, mainly written by Hymes, in the Institute of Governmental Studies Library in the basement of UCB’s Moses Hall. They were originally filed in 1946 in the Library for Economic Research at Berkeley.

The series of pamphlets includes:

- A Social Philosophy from Nursery School Teaching

- Must Nursery Teachers Plan?

- Who Will Need a Post-War Nursery School?

- Meeting Needs: The War Nursery Approach

- The Role of the Nutritionist

- Large Groups in Nursery School

- Should Children Under Two Be in the Nursery School?

Two unnumbered pamphlets titled “Toys to Make” and “Recipes for Foods for Children” were also mentioned in the report but copies are not available in the library. Teachers bought a total of 2,582 pamphlets at 15 cents each, according to the report dated December 1945.

Pamphlets offer nuggets

The pamphlet titled “Should Children Under Two Be in Nursery School?” addressed an issue the child care centers were forced to face head-on during the war. Generally, nursery schools did not take children under 2 because experiments had shown the younger children did not thrive in group settings. But the demand for care for infants was too high in the shipyards to ignore. They agreed to accept children as young as 18 months, and in Oregon alone, the centers enrolled 904 children 18 to 24 months of age.

“We therefore set out to plan a program which would include among other things: Provision for close and continuous relation of each child with one adult who would be responsible for him especially during eating, toileting and sleeping and during any time of emotional stress when he needed ‘mothering,’” wrote Stolz and Hymes.

Another key wartime lesson: “Food influences behavior. Small children…have pounded into us in unforgettable ways that hungry people are irritable; that they fight more; that they cry easily; that they become destructive…Some children we have seen, hungrier still, have told us that hunger can make people placid, inactive, lethargic,” Hymes wrote. In pamphlet 5, Miriam Lowenberg, chief nutritionist, discussed the crucial link between food and good health: “The (nursery school) nutritionist (helps) teachers … bring the child who needs medical care to the attention of a visiting nurse or doctor.”

The final report discussed other crucial issues such as: the need for child care services after the war for low-income women, costs of the child care operation including nourishing meals, methods of recruiting and retaining qualified teachers, nurses and counselors, providing weekly onsite professional development, and offering opportunities for staff to participate in policy decisions. Attempts to maintain a 10:1 child-to-teacher ratio for the children over 2 and a 5:1 ratio for the infants 18 to 24 months were mostly successful, the authors reported.

Kaiser experts shine on after war

After the war ended, Hymes gained national recognition as an author. Among his earliest best-selling booklets was “A Pound of Prevention” in 1947, which advised first-grade teachers on how to handle difficult “war babies.” He wrote that the “crybabies, whiners and bullies” were still suffering from the disruption of war. Hymes also wrote “How to Tell Your Child About Sex” (1949), “Behavior and Misbehavior: A Teacher’s Guide to Discipline” (1957), “Teaching the Child Under Six” (1968), and “Twenty Years in Review: A Look at Early Childhood Education 1971-1990.”

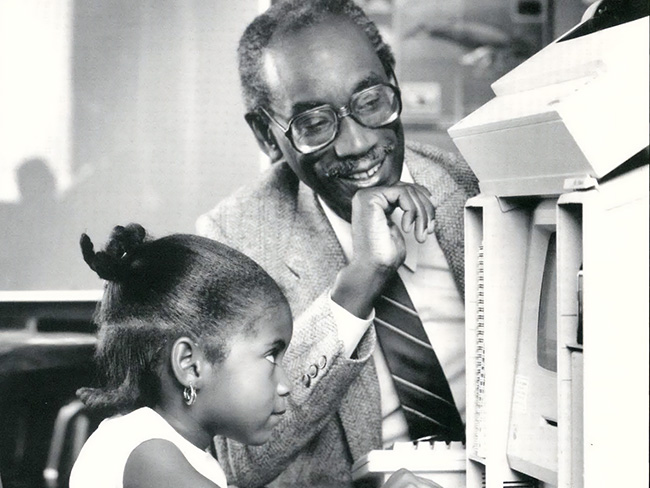

Hymes served in the Lyndon Johnson administration on the National Planning Committee for Head Start. He and Catherine Landreth both were instrumental in the development of the educational program for low-income children. Landreth was also known for her groundbreaking research in social perception. One of her studies found that children learn racial prejudice from their parents as early as three years old. She wrote three books that were influential in shaping early childhood education: “Education of the Young Child” (with Katherine H. Read), 1942; “The Psychology of Early Childhood,” 1958; and “Preschool Learning and Teaching,” 1972.

After the war, Stolz published “Father Relations of War-Born Children,” a study of how father-child relationships were affected by a father’s absence for war duty (1954); “Our changing understanding of young children's fears, 1920-1960” (1964), among other related works.