Physician publishes story of Permanente in the Northwest

Dr. Ian C. Macmillan's book provides a history of Kaiser Permanente and medical care in Oregon and Washington since the 1940s.

Permanente in the Northwest fills a large gap in the history of Kaiser Permanente — the unique contribution made by the Northwest Region, especially in the early years. Author and retired Northwest internist Ian C. MacMillan, who served 14 years as chief of medicine at Kaiser Permanente Sunnyside Medical Center, demonstrates an insider’s insight and enviable access to details that thoroughly enrich this account.

Before there was a Kaiser Permanente, there was Permanente Metals, the division of Henry J. Kaiser’s construction consortium that built ships during World War II. The medical services offered to those civilian workers were the kernel of what would eventually grow to become one of the nation’s largest not-for-profit health plans, and with two vibrant shipyards in Portland, Oregon, and Vancouver, Washington, the Northwest was a key participant.

The prologue provides a history of the medical care options in the area before 1941 as well as the story of how Sidney Garfield, MD, and industrialist Henry J. Kaiser came to collaborate on their successful model of prepaid industrial medical care. This is followed by a detailed account of the wartime boom — shipyards, housing, and health care rolled into one.

Wartime shipyards in Oregon and Washington

Notable events include the then-new practice of treating civilian tuberculosis patients with streptomycin, the model daycare program for workers’ children endorsed by Eleanor Roosevelt, and a rich art community.

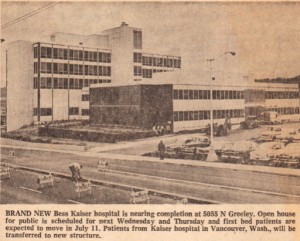

The demand for medical facilities soon outstripped the capacity of the first aid stations in the yards, and the first Northern Permanente Foundation Hospital was built in Vancouver, Washington, in 1942, followed by a second one across the Columbia River in Vanport, Oregon, a temporary community built for shipyard workers, the following year.

That hospital was kept out of the nearby metropolis of Portland through stiff resistance by the local medical establishment, an example of a contentious relationship that would last many years.

As happened in California, the exodus of shipyard workers after the war forced the Northwest medical care program to expand to the broader community. Ernest Saward, MD, who had administered the wartime health care plan for DuPont plutonium workers at Hanford, Washington, became the medical director of the physician group and the Northwest health plan in 1947.

Changes after World War II

Dr. MacMillan explores some of the fractious cold-war dynamics of the medical partnership at that time, including debates about how Kaiser Permanente internist Charles Grossman’s political activism was affecting the medical group’s relationship with the community.* (See note below.)

A large portion of the book is devoted to the history of various medical specialties of the Northwest medical group, detailing medical arcana more likely to be of interest to practitioners than a lay audience. The last three chapters trace significant chronological events in the region from the 1970s to the present.

Among these topics are the challenges of recruiting and retaining good doctors (he outlines the need for robust medical infrastructure, clear work policies, and adequate pay), the deep impact of the 1988 nurses’ strike, and the erratic steps taken by Kaiser Permanente to institutionalize an effective electronic medical record system.

Frank Stewart, administrator; George Wolff, architect, Dr. Wallace Neighbor (pointing); Northern Permanente Foundation Hospital, circa 1942.

Frank Stewart, Administrator; George Wolff, Architect, Dr. Wallace Neighbor (pointing); Northern Permanente Foundation Hospital, circa 1942

In all, this is a much-needed historical survey of a major region in the Kaiser Permanente constellation. Dr. MacMillan does not shy away from exploring awkward and complicated events in the Northwest Permanente history, and he writes with an insider’s viewpoint that enriches the accounts.

Permanente in the Northwest should be of interest to anyone interested in modern American health care policy, health practice, and the broader history of medicine.

"Permanente in the Northwest"

Ian C. MacMillan, MD, The Permanente Press, 2010

313 pp, with illustrations, bibliography, and index

Kaiser Permanente Northwest historical materials brought to Oakland

Preservation of the rich history of Kaiser Permanente’s Northwest Region got a boost at the end of 2011 when staff of the National Heritage Resources department in Oakland packed up over 100 cartons of Northwest photographs, clippings, newsletters, and files to fold into the Kaiser Permanente archives. These materials will be selectively processed over time and added to the existing collection, greatly enhancing our research capacity. The photographs accompanying this review were drawn from that collection.

Special thanks to Kaiser Permanente Northwest community benefit and external affairs staff Jim Gersbach and Mary Ann Schell for their help.

*After leaving Permanente in 1950 Dr. Grossman continued to practice medicine privately, and his political activism continued throughout his life (a path respectfully footnoted in MacMillan’s book in his Afterword titled “What Happened to the Pioneers?”). He was arrested in 1990 during a peaceful demonstration organized by Physicians for Social Responsibility, challenging the presence of a nuclear-armed battleship berthed near the Portland Rose Festival. His court testimony describes the scene:

“I was standing silently with several other doctors and a few others with a sign in my hand saying ‘Rose Festival is a fun time, we don’t need nuclear weapons.’ About 2:30 p.m. three or four policemen approached and asked us to leave. I asked why and was told that we have no right to stand in a city park carrying a sign. . . I put my sign down and said ‘OK I am not carrying a sign.’ He responded that if I did not leave within 30 seconds I would be forcibly removed. I said we were creating no disturbance and again asked why such a confrontation was necessary. While I was writing [down his badge and name] my two arms were forcibly seized, forced behind my back, and handcuffs were applied.”