A long history of equity for workers with disabilities

In Henry J. Kaiser’s shipyards, workers were judged by their abilities, not their disabilities. That spirit lives on today in Kaiser Permanente’s diverse workforce.

Allen Moreland’s story was featured in a 1943 issue of The Bo’s’n’s Whistle. He had an artificial leg and worked as a burner for the Oregon Shipbuilding Company.

In Henry J. Kaiser's 7 World War II shipyards, everyone could contribute to the home front regardless of ability. In fact, workers with disabilities could "do most jobs better than the average in the three shipyards," proclaimed The Bo's'n's Whistle, a shipyard publication for employees of Kaiser's Oregon Shipbuilding Company, on April 22, 1943.

The article explained that before the war, most businesses and industries shied away from hiring people with disabilities, even when the disability had nothing to do with the requirements of the job. "Then, along came the war with its terrific demand for manpower."

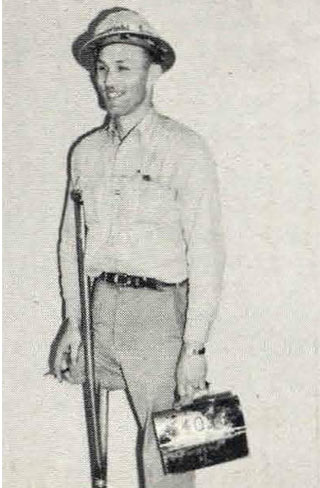

Warner H. Van Hoose, featured in a 1943 issue of The Bo's'n's Whistle, lost a leg at the age of 7. He worked as an Oregon Shipbuilding Company shipwright.

How the war changed hiring practices

Through the Selective Service Act, 10 million men were called to service in the armed forces. The departure of these "physically perfect specimens" wrote the Whistle, provided opportunities for people who remained at home, including those with disabilities.

And, when people with disabilities were given a chance to work, they proved themselves to be just as capable — if not more so — than the "physically fit." The Whistle concluded, "The secret of all production is to make the best use of the talents that ANY man has."

A similar publication called the Fore 'n' Aft, produced for the workers of Permanente Metals Corporation, Kaiser Com"" read a June 18, 1943, article. "As the armed forces and increased war needs drained the manpower market, other sources were tapped. Among them were the people with disabilities. Now the rest of America is learning what that important-but-forgotten million always knew:" People with disabilities could do almost any job as well as or better than many without disabilities.

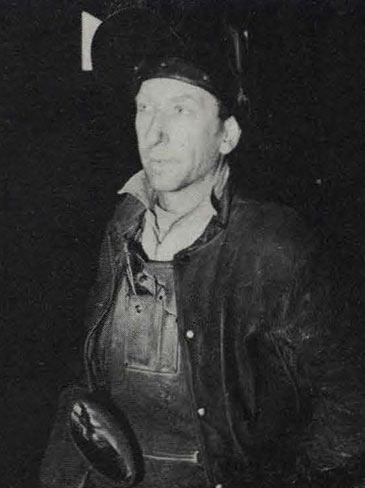

T.R. Wright, a welder with disabilities, worked at the Swan Island Shipyard in Portland, Oregon. This photo was featured in a 1943 issue of Bo's'n's Whistle.

Finding the right fit

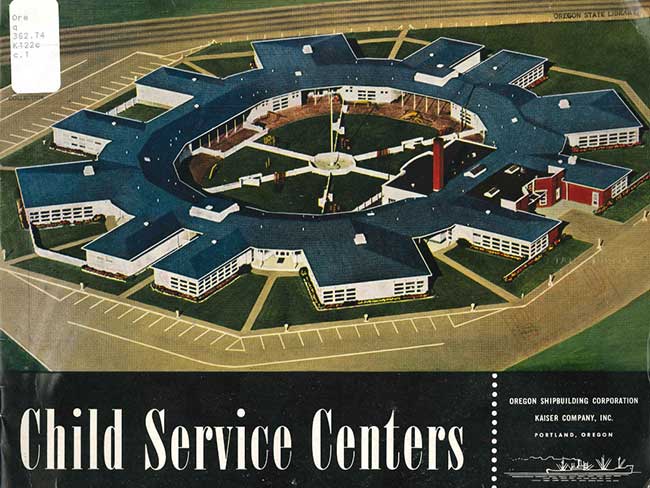

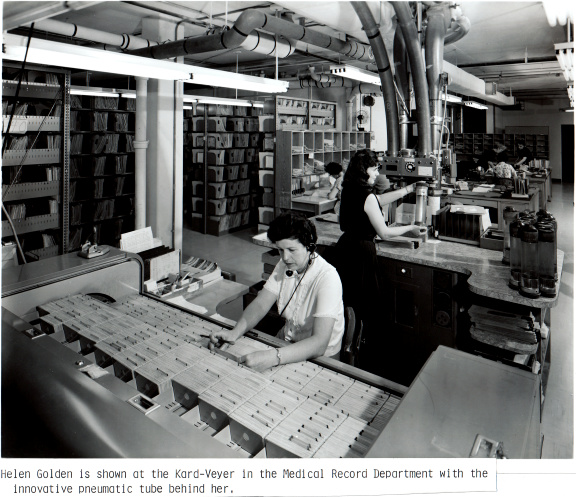

Making sure workers with disabilities had a job that fit their abilities required extra effort. In May 1944, Kaiser Foundation Hospitals and the Occupational Analysis and Manning Tables division of Region XII War Manpower Commission jointly published the 627-page report, Physical Demands and Capacities Analysis. One of the primary goals was to make sure that individuals were assigned to jobs they could perform without risk to their health. The report detailed over 600 distinct job titles in the shipyards.

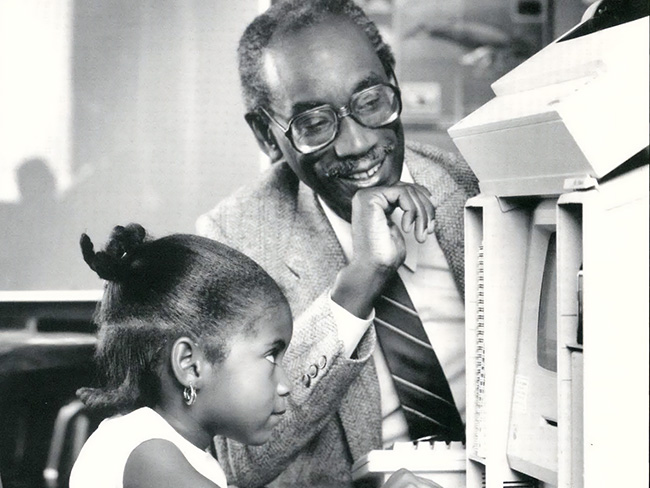

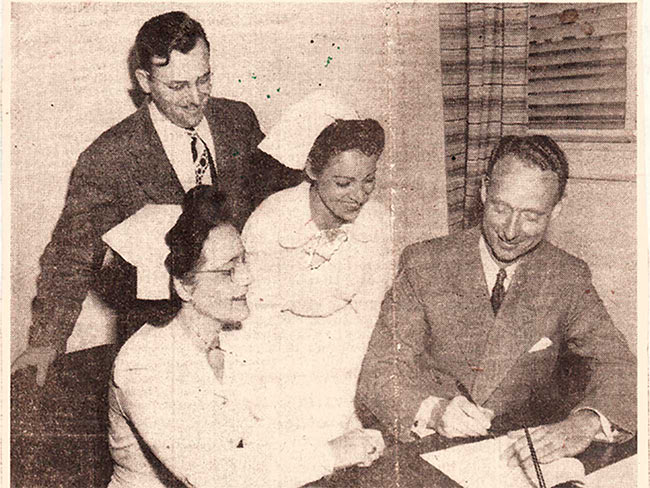

The shipyards also hired medical professionals to assist in placement efforts. One was Col. B. Norris, MD, who retired from the Army Medical Corps and was in charge of the Oregon Shipbuilding Company’s care for war veteran employees with disabilities.

Wartime hiring practices continue

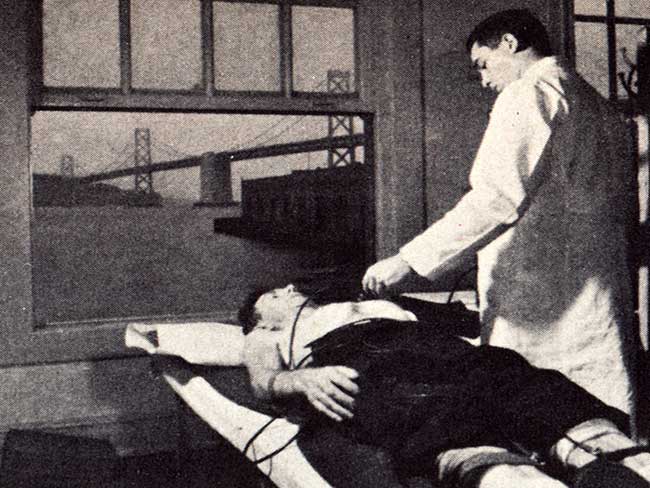

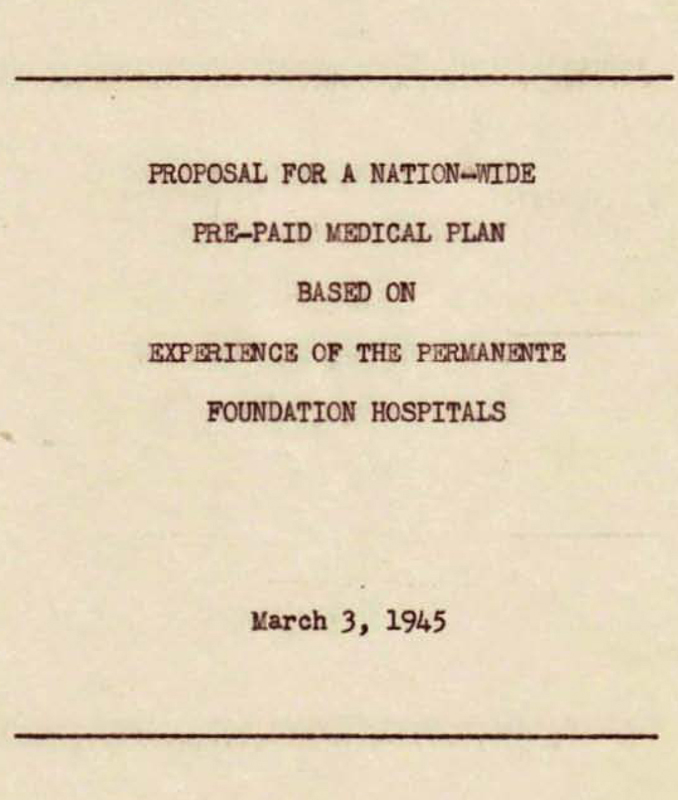

As the war wound down, inclusive hiring practices continued, expanding to include jobs outside the shipyards, thanks to rehabilitation services provided by the Permanente Hospitals.

"Because the Permanente Hospitals in Richmond and Oakland instituted vocational rehabilitation services with the cooperation of the State and Federal Bureaus, several former Richmond shipyard workers, who were injured or who suffered serious diseases, have been trained or are being trained in work which they can perform," read a July 20, 1945, article in Fore 'n' Aft titled "According to a man's abilities ..."

Col. Norris, MD, pictured here on June 29, 1945, headed the Oregon Shipbuilding Company’s care for disabled war veteran employees.

The Fore 'n' Aft described a typical example. “Ed [Andreas] was a painter on the ways in Yard One. He broke both feet, his ankle and pelvis bone when he fell from the scaffolding to the ground 40 feet below. Ed was unable to return to his former job and his case was referred to George Sloan, Richmond representative for the State Bureau of Vocational Rehabilitation. After an interview to determine his eligibility, Ed was sent to the San Francisco office, where he was given aptitude tests. One of the many counselors in this office discussed employment objectives with him, and today Ed is learning the trade of watch repairing.”

While inclusive hiring practices continued after the war at Kaiser Permanente, it would take the Americans with Disability Act signing on July 26, 1990, to prohibit discrimination against all people with disabilities. Since then, Disability Pride Month occurs each July.

Today, as in 1945, Kaiser Permanente works to ensure that individuals are seen for their abilities, not their disabilities. Learn more about our diverse workforce.