Equal pay for equal work

Kaiser shipyards in Oregon hired the first 2 female welders at equal pay as men during World War II.

March is Women’s History Month. On last year’s Equal Pay Day, Kaiser Permanente Chairman and CEO Bernard J. Tyson tweeted that, on average, American women must work 15 months to earn what men earn in a year. “At Kaiser Permanente, we are committed to ensuring equity in pay,” he wrote.

But the struggle for equal pay for equal work started long ago. One of its watershed moments was the World War II home front — and much of that took place in the Kaiser defense industries.

Access to jobs and pay equity for women were significant issues at the time, when the long-standing workforce changed dramatically. Healthy, white men went into the military, and industries needed workers it had never considered before.

Henry J. Kaiser was an atypical industrialist, and long before had learned that good labor relations and nondiscrimination — in any form — were smart business practices. With the notable exception of Japanese-Americans, Kaiser’s World War II shipyards embraced the most diverse workforce imaginable, including foreign nationals, the disabled, people of color, and women. Before World War II, women comprised approximately 13 million workers, but the war swelled that number up to 19 million.

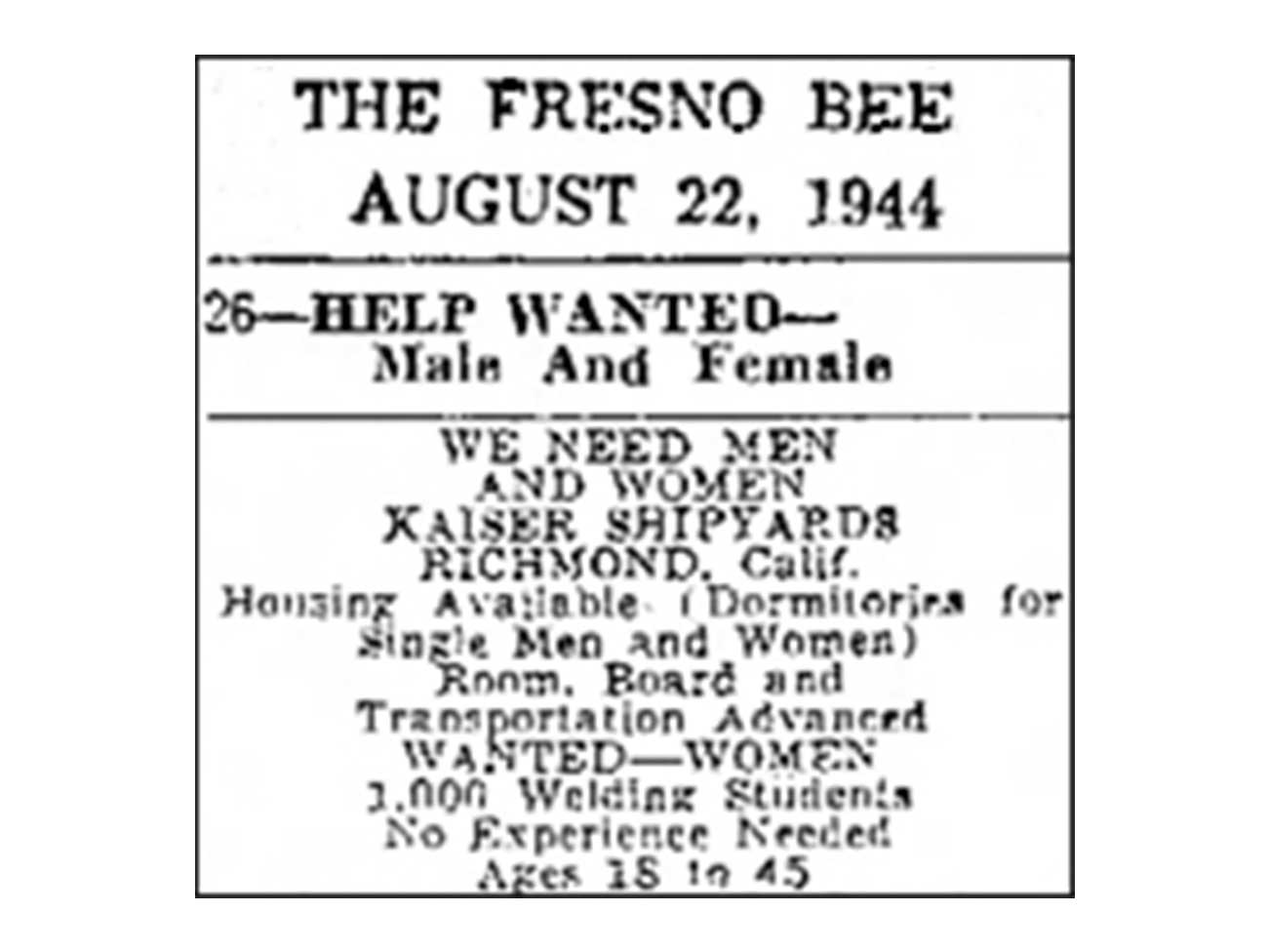

The home-front industries needed women workers, and appeals were made to their patriotism. Newspaper recruiting ads in the “Female Help Wanted” section went to great lengths to attract women. The Kaiser Aero-Fleetwings plant in Pennsylvania included a 372-word essay, “How to end the war the Kaiser Cargo way.”

The first 2 women to work as welders in America’s World War II maritime shipyards were Mary C. Carroll and Jeanne W. Wilde, hired at the Kaiser shipyards in Portland, Oregon, in the summer of 1942. They did the same work as men and were paid the same rate — $1.20 an hour.

Before the war, “women’s pay was consistently lower than men’s — except in Michigan, where such discrimination was a misdemeanor,” according to a November 22, 1942 Associated Press article “Women War Workers: They Don’t Know What It’s About, But They Get Results” by Amy Porter. “And the unions condoned this situation, since women held only interior ‘women's jobs’ and weren't numerous anyway. Pay differentials based on sex were written into many pre-war union contracts.”

The federal government set the tone for equal pay with the creation of the National War Labor Board at the beginning of 1942. In November of that year, it issued General Order No. 16, requiring companies to equalize pay between men and women. Historian Andrew E. Kersten noted that by January 1944, “the Board handled over 2,250 cases … resulting in wage increases for nearly sixty thousand women workers.”

It was no coincidence that the secretary of the U.S. Department of Labor under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was Frances Perkins, the first woman appointed to the U.S. Cabinet. In the groundbreaking 1942 bulletin #196, “‘Equal Pay’ for Women in War Industries,” the government’s position, expressed by Secretary Perkins and Mary Anderson, the director of the Women’s Bureau, was unequivocal: “Wage rates for women should be the same as for men, including the entrance rate.”

Although most unions supported the equal-pay goal, it was a moot point when women were barred from membership in some of them (as initially occurred with the Boilermakers’ Union, which during World War II was entrenched in protecting its white male base). But by late November, more than 3,000 women at the Kaiser Shipyards in Portland had received their union cards, and a similar influx of women into unions took place in Richmond, California.

That AP news story pointed out that, less than a year after Pearl Harbor, women had “managed to accomplish an industrial revolution all their own within a very short time” through the first large-scale unionization of women, winning the first legislation for equal pay through the War Labor Board, and revising “protective” legislation that hampered employment opportunities.

The 1942 AP article concluded with this optimistic view: “Now the equal pay principle is acknowledged, if not always lived up to. The West Coast leads the country in putting the principle into practice.”

More than 75 years later, “the principle” remains unresolved. Let’s roll up our sleeves and honor women workers.

November 4, 2025

A best place to work for veterans

As a 2025 top Military Friendly Employer, Kaiser Permanente supports veterans …

October 15, 2025

Kaiser Permanente shows up strong for the annual plane pull

Championing health equity and teamwork drives Kaiser Permanente’s support …

July 16, 2025

More than just a game

Kaiser Permanente partners with Special Olympics of Southern California …

April 30, 2025

A history of trailblazing nurses

Nursing pioneers lay the foundation for the future of Kaiser Permanente …

April 16, 2025

Sidney R. Garfield, MD: Pioneer of modern health care

Kaiser Permanente’s co-founding physician spread prepaid care and the idea …

March 27, 2025

We’re committed to mentorship, mental health, and communities

Kaiser Permanente awarded Elevate Your G.A.M.E. a grant to expand program …

March 25, 2025

AI in health care: 7 principles of responsible use

These guidelines ensure we use artificial intelligence tools that are safe …

March 17, 2025

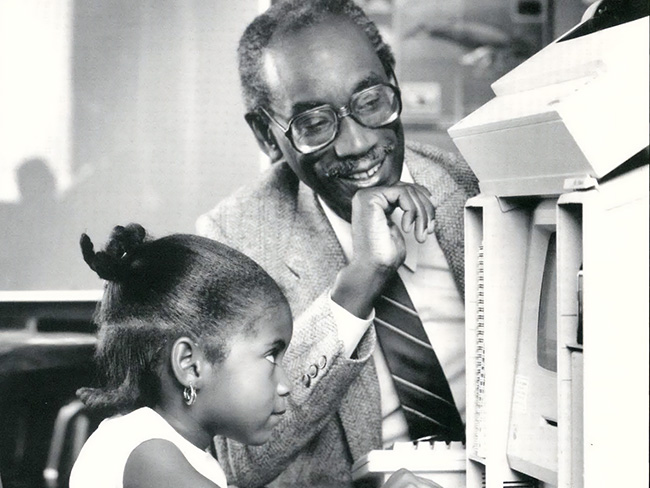

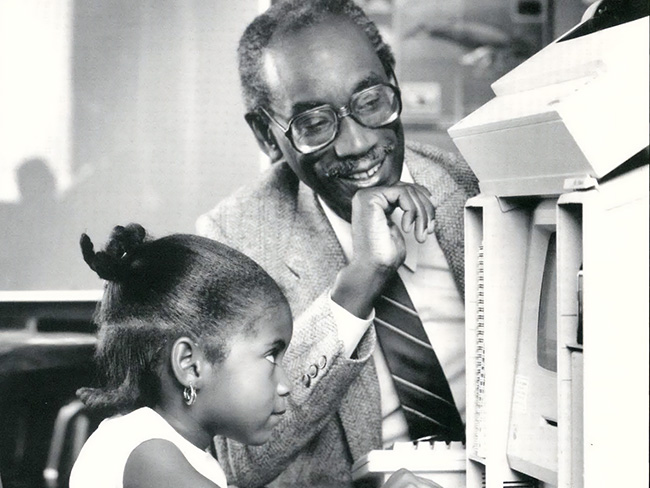

Remembering Bill Coggins and his lasting legacy

The founder of the Kaiser Permanente Watts Counseling and Learning Center …

December 26, 2024

Linking isolated communities to care

A collaborative partnership, powered by trusted nonprofit partners, brings …

December 16, 2024

Helping to build and support inclusive communities

At the Special Olympics Southern California Fall Games, Kaiser Permanente …

November 11, 2024

Health care coverage now accessible to uninsured people

Indigenous farmworkers may qualify for new Kaiser Permanente coverage.

November 11, 2024

Medicare telehealth flexibilities should be here to stay

We urge Congress to extend policies that have improved access to care and …

October 15, 2024

Our dedication to fostering well-being and equity

The 2023 Kaiser Permanente Southern California Community Health County …

October 2, 2024

Honored for supporting people with disabilities

Leading U.S. disability organizations recognize Kaiser Permanente for supporting …

September 16, 2024

Voting affects the health of our communities

In honor of National Voter Registration Day, we encourage everyone who …

July 16, 2024

Teacher residency program improves retention and diversity

A $1.5 million Kaiser Permanente grant addresses Colorado teacher shortage …

July 2, 2024

Reducing cultural barriers to food security

To reduce barriers, Food Bank of the Rockies’ Culturally Responsive Food …

June 19, 2024

Investments in Black community promote total health for all

Funding from Kaiser Permanente in Washington helps to promote mental health, …

May 30, 2024

Special Olympics Summer Games: Will you play a part?

Kaiser Permanente employee Carrie Zaragoza volunteers for Special Olympics …

May 14, 2024

Recognized again for leadership in diversity and inclusion

Fair360 names Kaiser Permanente to its Top 50 Hall of Fame for the seventh …

May 7, 2024

Can the badly broken prescription drug market be fixed?

Prescription drugs are unaffordable for millions of people. With the right …

May 3, 2024

Henry J. Kaiser: America’s health care visionary

Kaiser was a major figure in the construction, engineering, and shipbuilding …

April 12, 2024

It’s time to address America’s Black maternal health crisis

Health care leaders and policymakers should each play their part to help …

April 8, 2024

Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream is alive at Kaiser Permanente

Greg A. Adams, chair and chief executive officer of Kaiser Permanente, …

March 18, 2024

Program helps member prioritize her health

Medical Financial Assistance program supports access to health care.

March 6, 2024

Former employee honored for supporting South LA families

Bill Coggins, who founded the Kaiser Permanente Watts Counseling and Learning …

March 4, 2024

Taking care of Special Olympics athletes

Kaiser Permanente physicians and medical students provide medical exams …

February 13, 2024

A legacy of life-changing community support and partnership

The Kaiser Permanente Watts Counseling and Learning Center started as a …

February 2, 2024

Expanding medical, social, and educational services in Watts

Kaiser Permanente opens medical offices and a new home for the Watts Counseling …

December 20, 2023

Championing inclusivity at the Fall Games

Kaiser Permanente celebrates inclusion at Special Olympics Southern California …

December 7, 2023

Safe, secure housing is a must for health

We offer housing-related legal help to prevent evictions and remove barriers …

December 6, 2023

Solid foundation: How construction careers support health

Steady employment can improve a person's health and well-being. Our new …

November 1, 2023

Meet our 2023 to 2024 public health fellows

To help develop talented, diverse community leaders, Kaiser Permanente …

October 17, 2023

How Kaiser Permanente evolved

Sidney R. Garfield, MD, and Henry J. Kaiser came together to pioneer an …

September 13, 2023

Transforming the medical record

Kaiser Permanente’s adoption of disruptive technology in the 1970s sparked …

August 15, 2023

'Hot-spot' strategy gets more Californians vaccinated

A new location-based vaccine strategy by Kaiser Permanente was successful …

August 10, 2023

Highlighting our community health work in Southern California

The Kaiser Permanente Southern California 2022 Community Health Snapshot …

August 2, 2023

Social health resources are just a click or call away

The Kaiser Permanente Community Support Hub can help members find community …

June 30, 2023

Our response to Supreme Court ruling on LGBTQIA+ protections

Kaiser Permanente addresses the Supreme Court decision on LGBTQIA+ protections …

June 29, 2023

Our response to Supreme Court's ruling on affirmative action

Kaiser Permanente addresses the Supreme Court decision on affirmative action …

June 29, 2023

Special Olympics athletes go for the gold

Kaiser Permanente celebrated its sixth year as official health partner …

June 14, 2023

Honored for commitment to people with disabilities

The Achievable Foundation recognized Kaiser Permanente for its work to …

June 7, 2023

Engaging businesses for action on climate and health equity

New climate collaborative with BSR announced at joint Kaiser Permanente …

May 22, 2023

Investing and partnering to build healthier communities

Kaiser Permanente supports Asian Americans Advancing Justice to promote …

May 10, 2023

A workplace for all

We are building inclusive work and care environments where everyone feels …

May 10, 2023

Health equity, inclusion, and belonging

We strive for fairness, respect, and inclusion for all.

May 2, 2023

Women lead an industrial revolution at the Kaiser Shipyards

Early women workers at the Kaiser shipyards diversified home front World …

April 27, 2023

Inspiring students to pursue health care careers

Kaiser Permanente is confronting future health care staffing challenges …

April 25, 2023

Hannah Peters, MD, provides essential care to ‘Rosies’

When thousands of women industrial workers, often called “Rosies,” joined …

April 11, 2023

Collaboration is key to keeping people insured

With the COVID-19 public health emergency ending, states, community organizations, …

April 5, 2023

Housing help brings stability to patients’ lives

With medical-legal partnerships, we’re helping prevent evictions. Patients …

April 3, 2023

Hospital patients who are homeless connected to housing

A Kaiser Permanente program connects patients experiencing homelessness …

March 29, 2023

Supporting a safer future with public health

We’re partnering on 3 initiatives to strengthen public health in the United …

February 17, 2023

Good health starts in our communities: 2022 by the numbers

Kaiser Permanente supports total health in our communities in partnership …

January 17, 2023

Lawmakers must act to boost telehealth and digital equity

Making key pandemic-era telehealth policies permanent and ensuring more …

November 14, 2022

It’s time to rethink health care quality measurement

To meaningfully improve health equity, we must shift our focus to outcomes …

November 11, 2022

High-quality, equitable care

We believe everyone has a right to good health.

November 11, 2022

A history of leading the way

For over 75 innovative years, we have delivered high-quality and affordable …

November 11, 2022

Early leaders in equity and inclusion

Explore Kaiser Permanente’s commitment to equitable, culturally responsive …

November 11, 2022

Pioneers and groundbreakers

Learn about the trailblazers from Kaiser Permanente who shaped our legacy …

November 11, 2022

Our integrated care model

We’re different than other health plans, and that’s how we think health …

November 11, 2022

Our history

Kaiser Permanente’s groundbreaking integrated care model has evolved through …

November 8, 2022

Protecting access to medical care for legal immigrants

A statement of support from Kaiser Permanente chair and CEO Greg A. Adams …

October 14, 2022

Contact Heritage Resources

October 1, 2022

Innovation and research

Learn about our rich legacy of scientific research that spurred revolutionary …

July 29, 2022

Health care workforce

Strengthening America’s health care workforce

May 26, 2022

Nurse practitioners: Historical advances in nursing

A doctor shortage in the late 1960s and an innovative partnership helped …

March 22, 2022

Our commitment to equity and our LGBTQIA+ communities

A statement from chair and chief executive officer Greg A. Adams.

February 21, 2022

A best place to work for LGBTQ+ equality

Human Rights Campaign Foundation gives Kaiser Permanente another perfect …

February 14, 2022

Health care scholarships available

Kaiser Permanente in Hawaii to provide up to $100,000 in scholarships to …

September 10, 2021

‘Baby in the drawer’ helped turn the tide for breastfeeding

This innovation in rooming-in allowed newborns to stay close to mothers …

August 25, 2021

Kaiser Permanente’s history of nondiscrimination

Our principles of diversity and our inclusive care began during World War …

July 22, 2021

A long history of equity for workers with disabilities

In Henry J. Kaiser’s shipyards, workers were judged by their abilities, …

July 7, 2021

Achieving health equity

Equal medical care is not enough to end disparities in health outcomes.

June 2, 2021

Path to employment: Black workers in Kaiser shipyards

Kaiser Permanente, Henry J. Kaiser’s sole remaining institutional legacy, …

February 22, 2021

The Permanente Richmond Field Hospital

Forlorn and all but forgotten, it played a proud role during the World …

September 28, 2020

A legacy of disruptive innovation

Proceeds from a new book detailing the history of the Kaiser Foundation …

August 26, 2020

Kaiser Permanente’s pioneering nurse-midwives

The 1970s nurse-midwife movement transformed delivery practices.

July 30, 2020

Books and publications about our history

Interested in learning more about the history of Kaiser Permanente and …

May 18, 2020

Nurses step up in crises

Kaiser Permanente nurses have been saving lives on the front lines since …

November 8, 2019

Swords into stethoscopes — veterans in health professions

Kaiser Permanente has actively hired veterans in all capacities since World …

August 28, 2019

When labor and management work side by side

From war-era labor-management committees to today’s unit-based teams, cooperation …

August 2, 2019

Thriving with 1960s-launched KFOG radio

Kaiser Broadcasting radio connected listeners, while TV stations brought …

June 5, 2019

Breaking LGBT barriers for Kaiser Permanente employees

“We managed to ultimately break through that barrier.” — Kaiser Permanente …

February 5, 2019

Mobile clinics: 'Health on wheels'

Kaiser Permanente mobile health vehicles brought care to people, closing …

December 10, 2018

Southern comfort — Dr. Gaston and The Southeast Permanente Medical Group

Local Atlanta physicians built community relationships to start Kaiser …

May 30, 2018

John Graham Smillie, MD, pediatrician and innovator

Celebrating the life of a pioneering pediatrician who inspired the baby …

April 30, 2018

Nursing pioneers leads to a legacy of leadership

Kaiser Foundation School of Nursing students learned a new philosophy emphasizing …

April 19, 2018

Wasting nothing: Recycling then and now

Environmentalism was a common practice at the Kaiser shipyards long before …

April 12, 2018

Harold Hatch, health insurance visionary

The founding of Kaiser Permanente's concept of prepaid health care in the …

March 26, 2018

5 physicians who made a difference

Meet 5 outstanding doctors who advanced the practice of medical care with …

March 13, 2018

Henry J. Kaiser and the new economics of medical care

Kaiser Permanente’s co-founder talks about the importance of building hospitals …

March 8, 2018

Slacks, not slackers — women’s role in winning World War II

Women who worked in the Kaiser shipyards helped lay the groundwork for …

February 22, 2018

The amazing true story of Park Ranger Betty Reid Soskin

She is the oldest national park ranger in the country with a legacy of …

December 19, 2017

From boats to books: A history of Kaiser Permanente’s medical libraries

Kaiser Permanente librarians are vital in helping clinicians remain updated …

November 7, 2017

Patriot in pinstripes: Honoring veterans, home front, and peace

Henry J. Kaiser's commitment to the diverse workforce on the home front …

October 12, 2017

An experiment named Fabiola

Health care takes root in Oakland, California.

September 29, 2017

Harbor City Hospital: Beachhead for labor health care

The story of Kaiser Permanente's South Bay Medical Center finds its roots …

August 15, 2017

Sidney R. Garfield, MD, on medical care as a right

Hear Kaiser Permanente’s physician co-founder talk about what he learned …

August 10, 2017

‘Good medicine brought within reach of all'

Paul de Kruif, microbiologist and writer, provides early accounts of Kaiser …