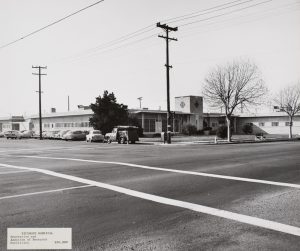

The Permanente Richmond Field Hospital

Forlorn and all but forgotten, it played a proud role during the World War II home front.

Richmond Field Hospital circa 1943.

A sprawling, single-story structure with a small tower sits at 1330 Cutting Boulevard in Richmond, California. Forlorn and all but forgotten, it played a proud role during the World War II home front and in the region’s subsequent history. It was a humble, working-class hospital that opened on August 10, 1942. It served thousands of patients until it closed in September 1995, when the new Kaiser Permanente Richmond Medical Center opened several blocks away.

When the United States was drawn into World War II in December 1941, Henry J. Kaiser was already running 2 shipyards in Richmond, building cargo ships for Great Britain. The existing workforce, composed primarily of healthy white men, soon went off to war. The tidal wave of replacement workers, new to the shipbuilding trade, performed under high-pressure conditions and were often in poor health from the start. Some 90,000 workers and their families migrated to the Richmond shipyards during the war, swamping all existing medical facilities. Enter the Field Hospital.

There were 6 first aid stations in Kaiser’s Richmond shipyards for immediate care, and the newly refurbished, 70-bed flagship Permanente Hospital in Oakland was the health plan’s biggest facility. But in between, just blocks away from the yards, was the Permanente Richmond Field Hospital.

At first, it only had 10 beds, but the demand for services was so high that before the year’s end, a 75-bed expansion was underway. Sidney R. Garfield, MD, who was in charge of the medical program, later reflected on the nearly constant expansion during the war: “Most of our mistakes ... came from underestimation.”

“They would be 20 deep in the hallways every day,” remembers Bernice Brooks, who went to work at the Field Hospital in January 1943.

Brooks was 1 of 7 25-year veteran Kaiser Permanente workers interviewed in a 1967 article celebrating the hospital’s 25th anniversary.

“We had 5 station wagons and 3 ambulances,” explained Ruth Schornick, a senior medical receptionist who spent 20 years in Emergency, starting in June 1943. “Invariably, we couldn’t find a driver. I had a chauffeur’s license, so I would have to go down to the shipyards to pick up the injured. And we also had to use the station wagons to bring the nurses and other employees to work and to take them home.”

“It became routine for the ambulance driver to stop by and pick up the X-ray technician or anesthesiologist whenever he picked up a patient at night that might require one of us,” added Olive Boyd, supervisor of Radiology.

The hospital was a significant asset to the Richmond community. An exhaustive survey of the field hospital produced in 2000 by the National Park Service includes this description:

"The addition begun in the spring of 1943 allowed for families of the shipyard workers to be cared for in the Field Hospital by their own physicians [on a fee-for-service basis since they were not yet included in the Permanente Health Plan]. This provided a great service to the city, as its population was quickly outgrowing existing medical facilities. Up to this point, the hospital had been serving workers’ families only in cases of emergencies. The new facilities included “complete gynecology, obstetric, surgery, medical, orthopedic and all allied clinics,” which operated on a twenty-four-hour basis. Additionally, as an experimental program, families living in the Harbor Gate and other residential developments were invited to visit the hospital for emergency treatment and office appointments on a fee-per-service basis."

Many institutions, including all branches of the military, the United Service Organizations, and hospitals, were segregated. Not the Permanente facilities. “Illness knows no color line here,” wrote a reporter from the San Francisco Bulletin in 1943 about the racial diversity of patients in line for treatment. “Red-helmeted men, women welders, Negroes, lined up for a checkup by the busy young doctors.”

An article titled “Berkeleyan Victim as Zoot-Suit Riots Spread” in the June 10, 1943, edition of the Berkeley Daily Gazette noted some of the racial tensions at the time and the role of this stalwart care facility:

"A young Berkeley Negro, Carl Oliver, said one of three unidentified sailors objected to his zoot suit garb and struck him on the forehead. Fearing serious trouble, he fled from the Richmond restaurant. At Richmond Field Hospital, Oliver was given emergency treatment and released. The victim is employed at Richmond Yard No. 1 as a burner, police said, and had stopped at the cafe on his way from work."

The commitment to inclusive care continued after the war’s end when the Richmond Field Hospital was again certified as a general treatment facility, accepting all patients regardless of race. Black physicians returning from military service needed hospital privileges and could get them at the Permanente Richmond Field Hospital because it had the beds.

In October 1945, health plan membership reached its lowest point: 14,500. Richmond Hospital resources and staff were diverted to Oakland Hospital, which served most of these members. For several months, the hospital ran on an outpatient basis only with a skeleton staff of not more than 20 to 25 employees. Years later in February 1959, Ellsworth Dougherty, MD, established a laboratory for comparative biology research with a staff of 30 people.

The hospital got a new lease on life in 1966 when it became the Kaiser Foundation Psychiatric Center’s site. One section was remodeled and refurbished to accommodate a 12-bed intensive care unit offering individual, group, and occupational therapy. The center provided both inpatient care and daycare.

Eventually, the hospital’s condition degraded, and in December 1973, the Kaiser Company purchased 5 acres in downtown Richmond to build a new hospital, a doctor’s office building, and a parking structure.

The new medical offices opened in 1979, with many departments moving there from the Field Hospital. Remaining at the old facility now referred to as the Richmond Medical Center, were the emergency department, inpatient services, physical therapy, pharmacy, laboratory, radiology department, and night and weekend clinics. The Field Hospital closed and the remaining services transferred to a new $56 million 4-building Kaiser Permanente medical complex in downtown Richmond in September 1995.

The site was purchased in 1999 by the Islamic Community of Northern California, which planned to renovate it into a community center and mosque, complete with Islamic architectural features. However, that conversion never happened, and the site remains mostly vacant.

A nomination for the Field Hospital to the National Preservation Registry was drafted in 2004, and although it is not listed by itself, the facility is registered as an element of the Rosie the Riveter WWII Home Front National Historic Park. The Historic American Buildings Survey concluded with a powerful appraisal of the importance of the Richmond Field Hospital:

"As one of the remaining World War II-era structures in Richmond, it represents an important historical moment, when thousands of workers converged on the small city to produce the hundreds of Liberty ships that helped to lead the Allied forces to victory. The Field Hospital is an outstanding contribution to the important narrative of the World War II American home front, demonstrating the great efforts made to provide social services to the thousands of men and women who labored in the defense industries during the war."

Ordinary people, doing extraordinary things.