Ellamae Simmons — trailblazing African American physician

Ellamae Simmons, MD, worked at Kaiser Permanente for 25 years, and to this day plays a central role in how Kaiser Permanente embraces diversity and inclusion.

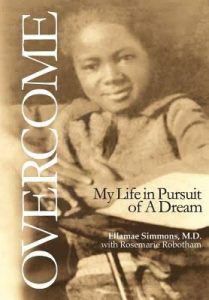

Overcome: My Life in Pursuit of a Dream

Ellamae Simmons, MD, with editorial collaboration by Rosemarie Robotham

Mill City Press, Minneapolis, 2016

Available via Google Books | Amazon

The arc of social justice relies on courageous individuals and Ellamae Simmons, MD, was one such individual. She was the first African-American woman to specialize in asthma, allergy, and immunology in the United States. She worked at Kaiser Permanente for 25 years, and to this day plays a central role in how Kaiser Permanente embraces diversity and inclusion.

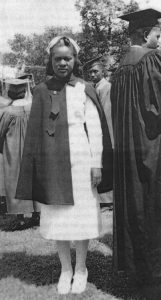

Dr. Simmons’ new biography at the age of 97 is a valuable contribution to that history. The book details her life and career, including graduating from Hampton (Virginia) nursing school in 1940, serving in the Army Nurse Corps during World War II, medical school at Meharry Medical College (Nashville) in 1954, and her Kaiser Permanente career.

Dr. Simmons’ chapter titled “The Interview” is about her coming to work at Kaiser Permanente during the summer of 1965. Dr. Simmons had been training in chest medicine at the National Jewish Hospital in Denver, at which Irving Itkin, MD, was her supervisor and mentor:

"When I told Dr. Itkin of my plan to move west at the end of my residency, he was full of advice. 'If you’re going to California,' he told me, 'there are only two places you should consider. One is the Scripps Clinic in La Jolla in Southern California, and the other is Kaiser Permanente in Northern California. Now,' he continued, warming to the subject of my future training as an allergist, 'Scripps is just another National Jewish. They write the same papers and conduct the same research. You’d basically be doing the same thing you did here'."

"At Kaiser, on the other hand, you’d round out your experience in a well-established outpatient allergy center, where asthmatics are well-maintained on an established anti-allergenic regimen. And I recommend Ben Feingold, the chief of asthma-allergy at Kaiser. He’s a good allergist and does fine research. Of course, he’s difficult…. but I recommend you go there and learn everything he has to teach you about asthmatics whose condition is well controlled, who are ambulatory, who go to school or to work. After that, you’ll be well set up to take care of anybody in this field.”

Dr. Simmons’ job interview with Ben Feingold, MD, has become a legend in Kaiser Permanente history:

"Dr. Ben Feingold sat back in his large bronze-studded black leather chair, scrutinizing me. He questioned me about my previous residencies, always calling me “Miss,” never “Doctor.” He asked me about my asthma-allergy fellowship, and more superficially about my chest medicine residency.

"After about 30 minutes, he tented his fingers on his desk and said, 'Well, I have my doubts about hiring anyone whom I have not trained, but please go out and see my secretary. We’ll have to continue this another day, as I have another meeting.' He told me to make an appointment with his secretary for the following Tuesday, which was five days away. I could ill afford the expense of additional nights at my hotel, plus meals, but I did not say this. Instead I made the appointment and spent the next few days exploring downtown San Francisco and biding my time.

"I returned the following Tuesday for the continuation of our interview and entered Dr. Feingold’s office as scheduled. Again the department chief sat back in his chair and viewed me intently. He asked a few questions about specific allergic reactions and how they might be treated at the institution of my residency. I answered easily and in meticulous clinical detail. At last, he said, 'Well, I see you know your stuff, but I’m afraid I cannot hire you, as I’ve never hired anyone whom I have not trained.'

“'Dr. Feingold,' I said, my voice steady, my gaze direct, 'I’ve never applied for a job for which I was not fully qualified. In fact, I’ve usually been overqualified. So tell me, is the real reason you’ve decided not to hire me the fact that I’m Black?'”

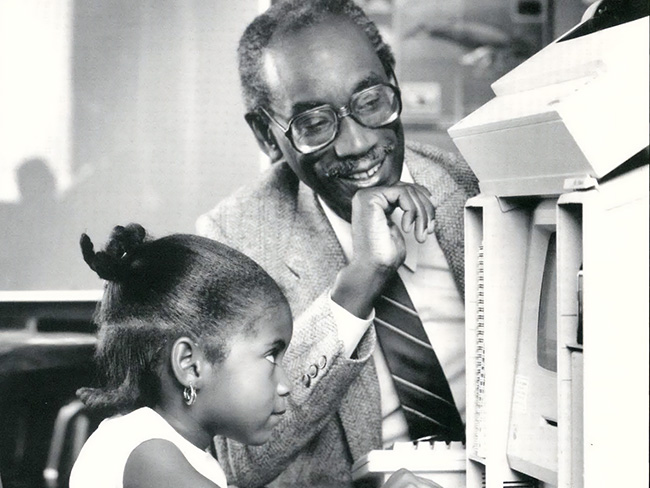

She asked Dr. Feingold if there were any other Black physicians at the Kaiser Permanente San Francisco hospital; it took him a while, but he finally remembered Granville Coggs, MD, a radiologist who’d joined the staff just a few months before. Dr. Simmons met with Dr. Coggs, and they shared experiences of racial discrimination pursuing their respective professions. She then returned to Dr. Feingold’s office, and resigned to not getting the position.

Dr. Feingold didn’t respond at first. He just stared at me in that fixed way I was already becoming used to. I realized he was wrestling with a decision.

Finally, he spoke. “Stop by my secretary on your way out and sign your contract,” he said. “I’ll take you after all.”

Among Dr. Simmons’ battles was that of housing discrimination. Even in the relatively progressive San Francisco Bay Area of the late 1960s, covenants and real estate practices perpetuated racially segregated neighborhoods.

This discrimination also was experienced by another early Kaiser Permanente physician, Eugene Hickman, MD. His unpublished memoir includes a chapter titled “House Hunting While Black”:

"My major problem in Oakland was with housing … I would phone all numbers regarding places within a radius that would afford reasonable access to the hospital where I was going to work. I was upfront with my racial identity, after which I would summarize my credentials, etc. The response was always the same: 'I am very sure you would be a very desirable member of our community, but we promised our neighbors we would not rent or sell to Negroes'.

"After several frustrating months, someone informed me of a place in Berkeley where I could go and apply for one of the homes that had been condemned to make way for the Grove-Shafter Freeway [California Highway 24]. We obtained an old house on 53rd Street, near Children’s Hospital. I was then able to move our family here. Then we began the search for a permanent residence. My wife would go out with an agent during the day while I was working; the children were not yet in school. Some idiots frequently mistook my wife for a southern European. One agent … suggested that if I wanted to see the house, I should come around after dark."

And if that wasn’t discouraging enough, Dr. Hickman experienced discrimination about his choice of a job from an unexpected source. The Sinkler-Miller Medical Association in Oakland (named in honor of two outstanding Black physicians) accepted him for membership but insisted on characterizing him “as some sort of traitor to the Black physician community” because of his affiliation with Kaiser Permanente.

Dr. Simmons’ personal story is a tribute to persistence and vision of overcoming adversity. Although we have come a long way in building social justice, there is always more to do — and pioneers such as Dr. Simmons inspire and guide us.