Kaiser Permanente’s early struggle to stand up to AIDS

New challenges provided collaborative opportunities for Kaiser Permanente to tackle the start of the AIDS epidemic in 1981.

Tom Waddell, MD, Olympic decathlete, SF physician, AIDS patient, and activist for better medical care for people with AIDS, 1987.

How did Kaiser Permanente, one of the nation’s largest not-for-profit health plans, deal with the outbreak of a new and unpredictable disease? Depending on who was talking in the 1980s, that answer ranged from “not nearly well enough” to “better than any other provider.” And both were true.

The epidemic appears

AIDS was first reported in the summer of 1981. The next year, when the Kaiser Permanente San Francisco Medical Center began treating its first patients, diagnosis and treatment protocols were in their infancy. Doctors, nurses, administrators, and other caregivers struggled to know what to do.

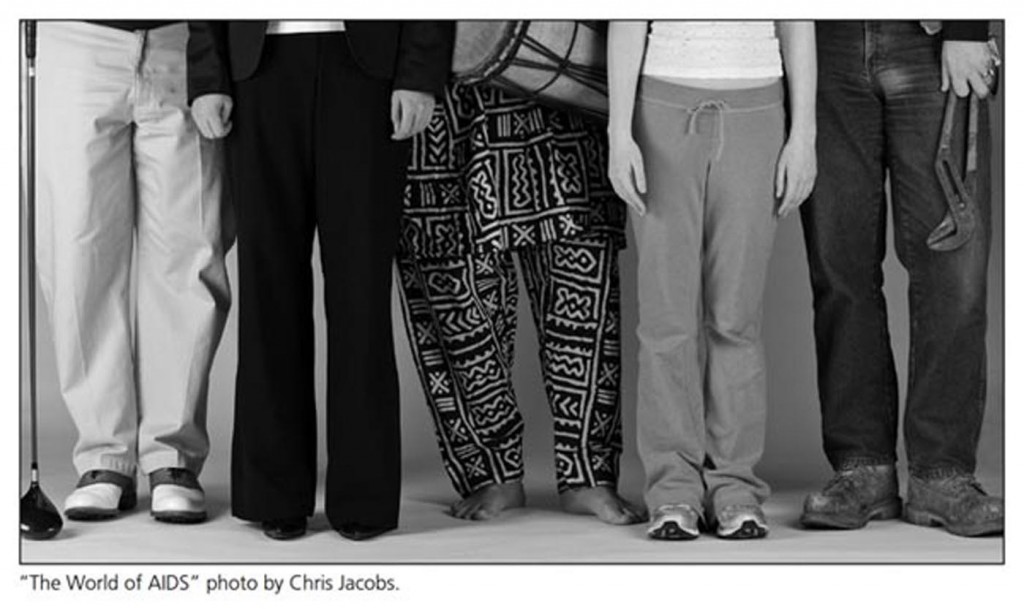

This illustration of a Kaiser Permanente physician with an AIDS patient was originally published with a 1988 article about AIDS and medical ethics in in-house publication, Spectrum.

Sometimes standard procedures worked fine, other times they were inadequate. One early conflict erupted in 1983 when two nurses at a Santa Clara, Calif., hospital (not a Kaiser Permanente facility) resigned over a dispute regarding caregiver safeguards in that facility’s first AIDS case. “I think most nurses would agree ... There really isn’t anyone who wants to go in the room,” one nurse said.

However, the president of the Registered Nurses Professional Association concluded that “enough precautions are being taken” per the hospital’s AIDS guidelines.1

At Kaiser Permanente San Francisco, Infection Control nurse Barbara Lamberto described Kaiser Permanente’s response:

“We called a department head meeting immediately [and] we talked about our personnel policies and our posture about that kind of situation, and I think in the long run it made a difference because everybody knew [that] this is how we felt. We are a health care organization. We are here to care for patients.“2

Michael Allerton, Operations and Policy Practice Leader for The Permanente Medical Group describes the situation as he saw it: “Here was a disease that was invariably fatal, in a horrible way, and nobody knew where it came from, how it was transmitted. . . and in this incredible environment of fear and anxiety, our doctors walked in those rooms. Our nurses walked into those rooms. Our engineers went in to fix the TVs. We had people who rose to the occasion.“3

The lack of solid data compounded the treatment of “the mysterious disease” in unexpected ways. In a 1985 interview, Kaiser Permanente San Francisco RN Grace Rico-Peña explained the challenge in the early years:

“This is very different than any other illness we’ve needed to educate about. We’re trying to dispel myths and rumors. When news media reports stories about AIDS they have a certain bias — they want to make things seem a little more dramatic, a little more exciting, and so they highlight certain parts of the story and get everybody all charged up about it.

“There are a lot of people with crazy ideas about AIDS. I remember one story about a bus driver who didn’t want to take money when he was in the “gay areas,” people who don’t want to wait on people. That’s part of our getting sensitized and taking care of these patients. AIDS patients frequently become social lepers.“4

She describes how Kaiser Permanente responded with reason and balance:

“Our philosophy in our educational approach, which has been dictated by our top-level administration here in Epidemiology, has been to not let ourselves get carried off into emotion, or political controversies, but to educate very solidly along the lines of the information that’s known. We’ve done educational programming always on the facts. [We ask] “What are our patients’ needs, how are we going to meet those needs?”

Patients get involved in care

And, as is true with all quality care, part of the solution came from the patients themselves. Tom Waddell, Olympic decathlete and a physician at San Francisco General Hospital’s emergency department, was diagnosed with AIDS in 1986.

Initially publicly critical of the treatment of AIDS patients at Kaiser Permanente San Francisco, he fought for better care. “I made a lot of noise,” he said. Other patients did so as well. On June 8, 1988, the Kaiser Patient Advocacy Union (with the suitably explosive sounding acronym “K-PAU”) was formed, demanding a voice in a range of issues. This was a life-and-death issue, and emotions flared.

But, as Dr. Waddell later admitted, “Much to Kaiser’s credit they responded. I think they may now have a model program for treating AIDS patients.”5 It was clear that motivated, informed patients needed to be part of the solution.

An HIV Support Group Program was established in 1988 at Kaiser Permanente San Francisco, and the next year a system-wide Kaiser Permanente HIV Member Advisory Panel was formed. In 1998, Kaiser Permanente hired the top San Francisco HIV specialist, Dr. Stephen Follansbee.

Documentary highlights Kaiser Permanente’s central role

In the year 2000, Critical Condition, an independent three-hour documentary about the politics of managed care, observed this high-stakes match between institutions and critics. One segment included footage of AIDS activists picketing Kaiser Permanente, angry that it moved slowly and would not prescribe medication other than standard and approved drugs.6

Tensions were high and tempers flared, but the strategic choice of Kaiser as a target was revealing:

“We only picketed Kaiser — not because it was the worst but because you knew where Kaiser was. It’s like the big kid on the block. If you can bring that kid to his knees, the others are going to get in line also.“7

Another protestor reflected on the choice: “Do I think those protests were effective? Absolutely. I think it slapped Kaiser in the face and I think Kaiser stood up to it and said, ‘Okay. What can we do here?’ ”

A third activist agreed: “The fact is we still have to acknowledge that Kaiser is the only HMO that I know of that’s ever allowed the members to come in and be part of the process.“8

The strength of many

The San Francisco Bay Area quickly became one of the national centers confronting the epidemic. By 1989 two cities (San Francisco and Oakland) accounted for 67% of the region’s cases. But other Kaiser Permanente regions were affected as well and mounted their own responses.

In 1989 Kaiser Permanente Colorado created an AIDS-specific social services program to help patients manage their own care, led by Barry Glass. Glass’ holistic model proved so effective that it was extended into other areas, including care of the elderly and those with catastrophic illnesses. Broader health care lessons were being learned.

Some answers were found through the strength of mass medical resources. In 1987 Kaiser Permanente established a multidisciplinary Interregional AIDS Task Force, expanding to an Interregional AIDS Committee the following year.

James Vohs, Kaiser Permanente health plan and hospital president and CEO in the 1980s, reflected on that process: “One of the best interregional committees that we established was in response to the AIDS epidemic. It was an excellent way to educate our other regions based on the experience that we had in Northern California, especially because we had so many AIDS cases.

“Kaiser covered something like 2 percent of the population of the United States when I was there, but we had about 5 percent of the AIDS cases. . . Having the Interregional AIDS Committee was very, very helpful in providing a good knowledge base of what was working, what wasn’t working, and how to organize services. It was extremely successful.“9

Kaiser Permanente continues to lead

Kaiser Permanente Educational Theater actors rehearse scene from 1989 Bay Area production of “Secrets,” a play about HIV/AIDS.

At the 30-year anniversary of the first diagnosis of the mysterious disease, Kaiser Permanente continues to be a leader in AIDS treatment and research, and in partnering with community-based efforts. Kaiser Permanente Southern California has provided grants totaling over $4 million to nonprofit organizations for a variety of services for people living with HIV and AIDS, including dental care, youth education and screening programs.

The nature of the epidemic has changed, but the work remains, and Kaiser Permanente has demonstrated its commitment to applying the full weight of its health care resources to finding solutions.

Learn more about Kaiser Permanente’s response to the AIDS epidemic at the Center for Total Health.

1Spokane, Washington Spokesman-Review, June 12, 1983.

2Transcript from Kaiser Permanente video interview, 3/1985; HIS07-508

3 Kaiser Permanente: 30 Years of HIV/AIDS with Coordinated Care, Compassion, and Courage , video produced by the Kaiser Permanente BSCPR Department winter 2011.

4Transcript from Kaiser Permanente video interview, 3/1985; HIS07-509

5Article in Spectrum, Summer 1987, p. 7.

6Jay Lubbers, from film transcript

7Dave Mahon, from film transcript, ibid.

8Mr. Sokolksi, from film transcript, ibid.

9James Vohs interview, courtesy of Regional Oral History Office. The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley. Berkeley, Calif., 94720-6000; Ascending the Ranks of Management, Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program, 1957-1992,” by Vohs, James A.; Malca Chall, editor, 1999 (issued)