Path to employment: Black workers in Kaiser shipyards

Kaiser Permanente, Henry J. Kaiser’s sole remaining institutional legacy, follows good business practices in hiring a diverse and inclusive workforce.

On September 30, 1942, the Daily Oregonian featured Kaiser’s group of diverse shipyard workers traveling west from New York to the Portland shipyards.

Before World War II, shipyards and unions made no special effort to hire women or Black employees. However, soon after the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, it became clear to industrialist Henry J. Kaiser that a diverse industrial workforce would be essential for defense production on the American home front as many white men went away to war.

The problem: Unions’ exclusionary rules

By federal law, the shipyards were closed shops and could only employ union members. But the International Brotherhood of Boilermakers, Iron Ship Builders, and Helpers of America, the largest of the shipyard unions, would not allow Black shipyard workers as equal members.

Kaiser was known for working well with organized labor, but the union’s exclusionary membership policies were an impediment to employment and production. When Kaiser at first tried to hire workers directly without going through the union, he began one of the most fundamental struggles between management and labor. At stake was the right of all workers to gainful employment without discrimination.

To address the hiring issue in 1937, the International Brotherhood of Boilermakers, Iron Ship Builders, and Helpers of America created a “separate but unequal” membership tier for Black workers. These were called “auxiliary” locals (the Richmond, California, auxiliary was called A-36), and they limited members’ job opportunities, grievance procedures, and voice in union affairs. By 1942, over 1,500 Black workers were members of these auxiliaries, but as wartime employment increased, so did racial tension over these limitations.

A Kaiser shipyard hiring spree

The first skirmish in this battle took place in Portland, Oregon. Kaiser’s eldest son, Edgar, was in charge of 3 shipyards there, and he sought help in hiring as many people as he could. He found a responsive official in Anna Rosenberg, the New York regional director of the War Manpower Commission, who authorized the United States Employment Service to support the recruitment of Kaiser’s workers without union clearance in early September 1942. People signed up at a rate of 400 an hour and then headed west to the Kaiser shipyards in Oakland, Portland, and in Vancouver, Washington. After the initial hiring spree, the Daily Oregonian reported on September 30, 1942 that Henry J. Kaiser’s “Magic Carpet Special,” a train from New York to Vancouver, carried 30 Black workers among the 490 passengers.

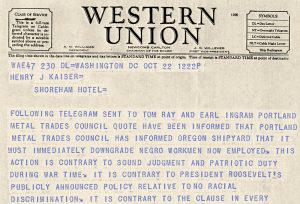

Telegram from John P. Frey (president of the American Federation of Labor’s Metal Trades Department) about labor issue involving Black workers in Portland yards, 10/22/1942

Earlier that month, 8 Black shipyard workers were promoted to skilled positions in Portland. Tom Ray, secretary and business agent for Portland’s Boilermakers Local Lodge 72, threatened that the union would “take matters into its own hands” unless Kaiser revoked the promotions from common laborers to skilled tradesmen.

Local Lodge 72 also refused to hire the 30 Black workers who traveled from New York, except for menial jobs. The conflict forced Anna Rosenberg to withdraw support from Kaiser’s hiring program. The tension between Kaiser and Local Lodge 72 reached residents in Portland’s Albina district who “protest[ed] further influx” of Black workers and demanded the construction of dormitories for Black workers to stop.

It wasn’t until October 7, 1942, that the Portland Kaiser shipyard and the Boilermakers union agreed to permit Black workers to be employed at the shipyards, “… making use of ‘their highest skills’ in all departments.” But that interpretation was up to the union.

Pressing onward for fair hiring

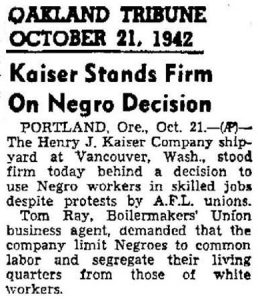

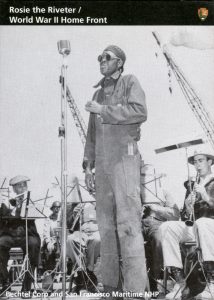

Newspapers conveyed Henry J. Kaiser’s commitment to hiring a diverse workforce, one of Kaiser Permanente’s founding values.

The Oakland Tribune reported on October 21, 1942, that the Henry J. Kaiser Company shipyard in Vancouver would continue to hire black workers for skilled jobs despite protests by the American Federation of Labor unions.

The next major clash happened at a Kaiser shipyard in Vancouver. In mid-December 1942, a representative for 150 Black shipyard workers at Kaiser’s Vancouver yard charged that the auxiliary union represented “downright open discrimination.” And in Oregon, hamstrung by the inflexibility of the Boilermakers after months of talks, more than 300 Black workers were forced off their jobs in July 1943 for refusing to join the auxiliary.

In November 1943, Bechtel Corporation’s Black workers at the Marinship Corporation shipyard in California stopped working after the Boilermakers said they would fire 430 Black workers for failure to join the auxiliary. The Marinship workers went to court with Joseph James as the plaintiff on behalf of himself and 1,000 others. James claimed that Black workers at their shipyard were forced to join the auxiliary union without gaining union privileges. Intervention by the Fair Employment Practices Commission resulted in a favorable ruling of James v. Marinship in early 1944, and the ruling was later upheld by the California Supreme Court. By then the war, and shipyard production, was almost over.

The Boilmakers union today

In James v. Marinship, 1944, the California Supreme Court ruled in favor of Joseph James, outlawing union practices based on racial discrimination.

Betty Reid Soskin, the country’s oldest national park ranger, works at the Rosie the Riveter World II Home Front National Historical Park on the site of the bustling Kaiser Richmond shipyards. She was a clerk for the all-Black Boilermakers Union A-36, and appreciates how the union has come a long way toward correcting past injustices. Today, the union is a major supporter of the park and actively recruits women in the trade.

Kaiser Permanente, Henry J. Kaiser’s sole remaining institutional legacy, follows good business practices in hiring a diverse and inclusive workforce. We are proud to have been part of the struggle to achieve equal opportunity, led by disenfranchised workers eager to do their part for America and supported in that effort by an enlightened business leader: Henry J. Kaiser.