We must grow the health care workforce

At Kaiser Permanente, we educate future clinicians and offer programs that bring new health care professionals into our communities. We urge policymakers to take action to grow the health care workforce.

The U.S. is facing a health care worker shortage that will continue for the foreseeable future.

Too few workers are entering the health care field. More health care professionals are leaving their jobs due to retirement or burnout.

But with our country’s aging population, we’ll need even more health professionals in the years to come.

Kaiser Permanente is taking steps to expand and upskill the health care workforce. We’re prioritizing professions with the biggest shortages and highest demand. This includes mental health care workers, nurses, and primary care doctors.

We urge policy leaders to address this critical issue.

Health care staffing shortage

The number of people age 65 and older in the U.S. will increase by almost 50% by 2050.

As the U.S. population ages, more people need medical care for both short-term problems and ongoing health conditions. And yet the shortage of health care professionals means many people have trouble getting the care they need when they need it.

Projected nationwide shortages include:

The shortages are even more acute in certain areas of the country. Nearly 3 million Americans live in areas that lack both health care facilities and reliable high-speed internet. Without high-speed internet, telehealth isn’t an option for care.

Solving the workforce shortage isn’t as simple as hiring more people or using technology to leverage existing clinicians. That’s because the shortages exist for a number of reasons, including:

- The high cost and time required to complete health care degree programs

- The time commitment required to become fully licensed, especially in the field of mental health

- Limited space in existing educational programs to take in more students

- Burnout that has led to more resignations (over 35% of health care workers report feeling burned out)

- Many current health care professionals reaching retirement age

Addressing training needs

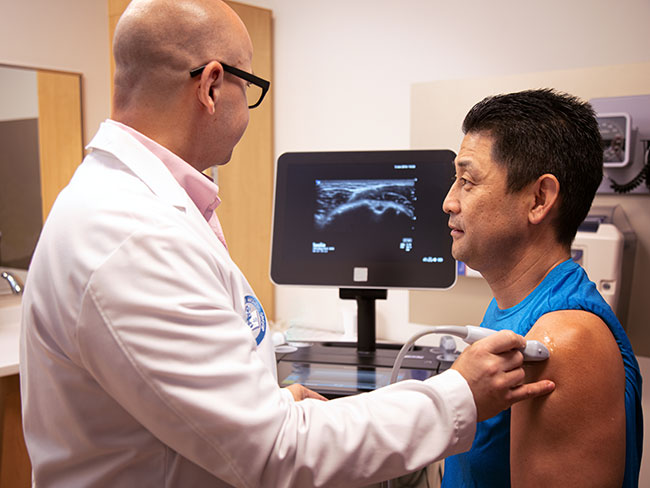

At Kaiser Permanente, we support clinical education and training opportunities to address the health care worker shortage.

We’re focused on the high cost of education and the extensive time commitment needed to become fully licensed. Our goals are to:

- Bring more professionals into health care roles where they’re needed most

- Help skilled professionals enter the field as quickly as possible

We’ve created schools and programs to help us achieve these goals.

- The Kaiser Permanente Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine trains approximately 50 physicians annually. We recently graduated 48 medical students, with almost half heading into primary care.

- The Kaiser Permanente National RN Residency program helps approximately 600 nurses each year transition from academia to professional practice.

- The Kaiser Permanente School of Allied Health Sciences provides academic and clinical training. It also helps students find jobs in mental health counseling, radiology, nuclear medicine, ultrasound technology, medical assisting, and phlebotomy.

We also have programs specifically for the field of mental health.

- The Mental Health Scholars Academy provides financial assistance and training for Kaiser Permanente employees who want to become mental health therapists, counselors, or social workers.

- The Mental Health Workforce Accelerator removes barriers to licensure for master’s-level students and graduates. The programs offer salary stipends, options for clinical supervision, and job placements during the licensure process.

- The Mental Health Post-Master’s Associate Program helps mental health graduates get the supervised clinical hours they need to obtain a license to practice.

These programs are making a difference. But the workforce shortage is a problem greater than any one organization can solve. We need support from policy leaders.

How policymakers can help

To help solve the health care worker shortage, policy leaders should:

- Expand and reform graduate medical education to train more health care professionals in areas of greatest need, such as primary care, psychiatry, and addiction medicine

- Support programs that offer tuition assistance, loan forgiveness, scholarships, and stipends across in-demand health fields

- Support programs that help mental health graduates get the supervised clinical practice hours required for licensure

- Promote the effective use of community health workers and peer support specialists

- Remove barriers to telehealth and support the safe use of virtual care across state lines, so that more people can get the care they need, no matter where they live

- Invest in team-based and integrated care to create efficiencies and prevent burnout

- Streamline licensing requirements, especially in mental health, to avoid therapists being subject to different requirements in different states

We took a more in-depth look at the issue of licensure during our recent Kaiser Permanente Institute for Health Policy forum.

Policy changes such as these can ensure the U.S. has enough health care workers to care for all patients — now and in the future.