The healing language of cancer

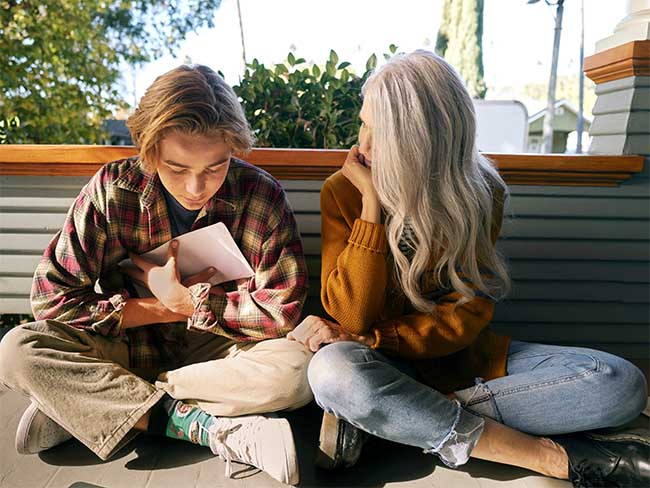

A Kaiser Permanente radiation oncologist shares how giving patients a voice on how we talk about their illness can provide comfort and healing.

Sometimes, when we talk to patients who have cancer, we say the wrong thing, over and over and over. We tell them they’re in the midst of a battle, or a war. We tell them they can beat it if they fight it, if they’re strong, if they never give up.

But what if all the pain, suffering, and indignity they’ve endured in chemotherapy has left them wanting to close their eyes and rest peacefully in the knowledge that their time has come? Urging them to fight is not going to make them feel better. It might make them feel worse — as if they did not try hard enough and failed.

“There’s better healing language that can be used,” says Katie Deming, MD. “But it’s going to be different for everyone.”

Giving the patient a voice

Dr. Deming is a radiation oncologist and former medical director of cancer services for Kaiser Permanente in Portland, Oregon. She wants to change the way we talk to patients with cancer. Specifically, she wants to give the patients a voice in how we discuss their illness. She recently gave a TEDx talk in Reno, Nevada, titled How to Talk to Someone With Cancer.

About a decade ago, Dr. Deming and her colleagues surveyed 1,400 patients who had breast cancer to share their feelings about the term “cancer survivor.” She wasn’t prepared for the results: 60% of the respondents considered the term “survivor” to be negative. Patients said it didn’t accurately reflect their unique experience of cancer. Others felt as if they were tempting fate to say they’d “survived.” Some expressed anger, saying they had stage 4 cancer and that survival wasn’t likely.

“This made me really pay attention to the language I used,” Dr. Deming said recently. “And when I started looking more closely, I realized we tend to use a lot of battle language, like ‘Win the fight.’ I also noticed that these terms were not helping my patients.”

Emotionally charged language

When it comes to cancer, most of us rely on language that suggests “fighting” means it can be “beaten,” a comforting sentiment that puts off unpleasant thoughts about death and provides a sense that the illness is temporary and soon everything will be back to normal.

But it can mean something else entirely for the patient. Some may feel compelled to give chemotherapy or other treatments another try because they don’t want to “give up the fight” and disappoint their family when they’d really rather accept their mortality and die on their own terms. Using the language of the battlefield doesn’t motivate these patients. In fact, in some cases it may increase cortisol levels and anxiety and weaken the immune system. Rather than being calming and supportive, this language could aggravate their suffering.

So, Deming is trying to start a different conversation and it starts by putting the patients’ needs first. And to find out what exactly the patient needs, the best start is to ask them.

“It’s ok to say, ‘I want you to know I’m here for you and I want to know what’s most supportive for you.’”

When Dr. Deming asked a close family member with breast cancer how she could be most supportive, her relative said she loved to see photos of house pets. So, rather than daily texts that put the onus on the patient – How are you? – Dr. Deming sent along photos of her pets.

They were a big hit — which isn’t surprising. Laughing at a cat chasing its own tail is a nice respite from “fighting for your life.”

July 11, 2024

Transforming education and mental health in Watts

Our investment in the Watts neighborhood of California, in partnership …

June 28, 2024

Health Action Summit highlights mental health opportunities

The Kaiser Permanente Colorado Health Action Summit gathered nonprofits, …

June 27, 2024

5 facts about autism

A Kaiser Permanente doctor shares key details. By learning more about autism, …

June 19, 2024

Investments in Black community promote total health for all

Funding from Kaiser Permanente in Washington helps to promote mental health, …

June 17, 2024

A culture of caring eases a cancer journey

Exceptional, personalized radiation oncology care helped Maura Craig treat …

June 13, 2024

Conquered 2 cancers while climbing mountains

Chris Hogan faced kidney cancer and prostate cancer at the same time. He …

June 3, 2024

A call to ‘Connect’ for cancer prevention research

Participate in a study to help uncover the causes of cancer and how to …

May 31, 2024

Stage 4 lung cancer: A story of hope

A young father is enjoying “bonus time” with his kids thanks to new targeted …

May 21, 2024

Surviving stage 4 lung cancer with immunotherapy treatment

Patients like Carol Pitman are living longer thanks to advances in lung …

May 14, 2024

A key ally in navigating mental health care for kids

Behavioral health consultants can provide a better understanding of often …

May 10, 2024

Self-care is key for new parents

Feeling emotional or overwhelmed after a new baby’s arrival? You’re not …

May 7, 2024

Making cancer care more convenient in Southern California

Kaiser Permanente has opened a new Radiation Oncology Center at the Bellflower …

May 3, 2024

Lonely and depressed — but not alone

After a lifetime of feeling isolated, Moth Wygal finds connection thanks …

April 29, 2024

Soccer star: ‘Let’s talk about mental health’

Naomi Girma, a sports ambassador for Kaiser Permanente, is passionate about …

April 17, 2024

5 common health conditions men don’t like to talk about

Some of the most common conditions affecting men carry a social stigma …

April 10, 2024

For a new mom, talking about her worries helped her heal

One in 5 people experience depression, anxiety, or other mental health …

April 1, 2024

Lynch syndrome: Managing the risk of hereditary colon cancer

Lynch syndrome is a gene mutation that increases colon cancer risk. Learn …

March 20, 2024

Life after cancer: Surviving and thriving

A healthy life after cancer is possible. Learn how Kaiser Permanente helps …

March 6, 2024

Joining a national effort to test new ways to find cancer

As part of the Cancer Screening Research Network, our researchers will …

March 6, 2024

Colon cancer screening: She’s glad she didn’t wait

A timely preventive test reveals Rebecca Kucera has cancer. Swift treatment …

March 5, 2024

Researchers look for ways to find pancreatic cancer early

Early detection of the disease, before it becomes advanced, will increase …

February 26, 2024

What you need to know about colon cancer screenings

Screening for colorectal cancer is recommended for most people starting …

February 21, 2024

From planning his funeral to celebrating his wedding

Gabriel Abarca had no hope for his future. Then the team at Kaiser Permanente …

February 21, 2024

Recovering at home after a double mastectomy

Innovative surgical recovery program helps breast cancer patients safely …

February 13, 2024

A legacy of life-changing community support and partnership

The Kaiser Permanente Watts Counseling and Learning Center started as a …

February 12, 2024

Proposition 1 would bolster mental health care in California

Kaiser Permanente supports the ballot measure to expand and improve mental …

February 8, 2024

Road to heart health: Living well

You have only one heart. ‘Prescribe’ yourself a few changes to help protect …

February 2, 2024

Expanding medical, social, and educational services in Watts

Kaiser Permanente opens medical offices and a new home for the Watts Counselin …

January 29, 2024

Empowering minds to help others thrive

Supporting behavioral and mental health in communities where needs are …

January 24, 2024

A full-circle journey for one cancer survivor

Grateful for compassionate and successful Hodgkin lymphoma treatment at …

January 23, 2024

How to bolster your child’s self-esteem

Everyday Health

January 22, 2024

Solutions for strengthening the mental health care workforce

Better public policies can help address the challenges. We encourage policymak …

January 10, 2024

‘You don’t know unless you ask them’

Kaiser Permanente’s Patient Advisory Councils help us create exceptional …

January 3, 2024

Addressing the shortage of mental health workers

There aren’t enough mental health professionals in the U.S. to meet the …

December 26, 2023

How to prevent cervical cancer

Cervical cancer is highly preventable. Learn how HPV vaccination and regular …

December 13, 2023

Nurse navigators guide patients from diagnosis to treatment

An unexpected cancer diagnosis left Jennifer Martin unsure of the next …

December 7, 2023

Safe, secure housing is a must for health

We offer housing-related legal help to prevent evictions and remove barriers …

December 6, 2023

Leading research with gratitude

Learn how you can participate in a study to uncover what causes cancer …

December 1, 2023

Surviving — and thriving — after cancer

From diagnosis to recovery, David Parsons, MD, shares how screening, treatment …

November 29, 2023

Tapping into an array of mental health options

Pavan Somusetty, MD, explains how people who need support and guidance …

November 21, 2023

Surviving lung cancer as a nonsmoker

As a lifelong nonsmoker, Mariann Stephens was shocked to learn she had …

November 1, 2023

Tips for healthy holiday travel

Six steps help you prep for winter trips.

October 25, 2023

Breast cancer during pregnancy: Caring for mom and baby

A team of specialists treats an expecting mother’s cancer while keeping …

October 24, 2023

Childhood anxiety: What parents need to know

A child and adolescent psychiatrist shares tips on supporting your child …

October 23, 2023

A renewed sense of purpose after surviving breast cancer

Joy Short, a Kaiser Permanente member and employee, turned her breast cancer …

October 11, 2023

Early breast cancer detection improves quality of life

For 75-year-old Peggy Dickston, a surprise diagnosis was caught early thanks …

October 11, 2023

Bridging the mental health gap

Kaiser Permanente’s partnership with Fontana Unified School District brings …

September 27, 2023

Harvest your power

Use biofeedback to help manage stress.

September 27, 2023

From suicide survivor to mental health advocate

Former Major League Baseball player Drew Robinson shares his story of hope …

September 13, 2023

Mental health champion: A mission inspired by personal loss

San Diego Wave Fútbol Club star defender Naomi Girma, Kaiser Permanente …

September 6, 2023

Recovery from addiction is possible

Our clinicians help patients get the care they need to move forward with …

August 28, 2023

Grants improve the total health of our communities

Kaiser Permanente increases access to mental health services in Southern …

August 22, 2023

Mental health

Expanding access to high-quality mental health services

August 17, 2023

Beyond clinic walls: Research supporting healthy communities

Stories in the Department of Research & Evaluation 2022 Annual Report demonstr …

August 17, 2023

Cancer research: The role of immunotherapy

Research and clinical trials play a vital role in advancing cancer treatment …

August 16, 2023

Cervical cancer screening: Exploring the at-home HPV test

Kaiser Permanente is at the forefront of cervical cancer research. Find …

August 15, 2023

Screening for breast cancer: Mammogram guidelines

Mammograms can help detect breast cancer early, when it’s easier to treat. …

August 14, 2023

Marla’s story: Surviving acute promyelocytic leukemia

After a diagnosis for a rare type of blood cancer, Marla Marriott got high-qua …

August 10, 2023

Successfully navigating the school year

These tips from Don Mordecai, MD, Kaiser Permanente’s national mental health …

August 8, 2023

Genetic testing and customized cancer care

Harold Newman had advanced prostate cancer. Genetic testing helped expand …

August 4, 2023

Eating well and adopting healthy habits helps prevent cancer

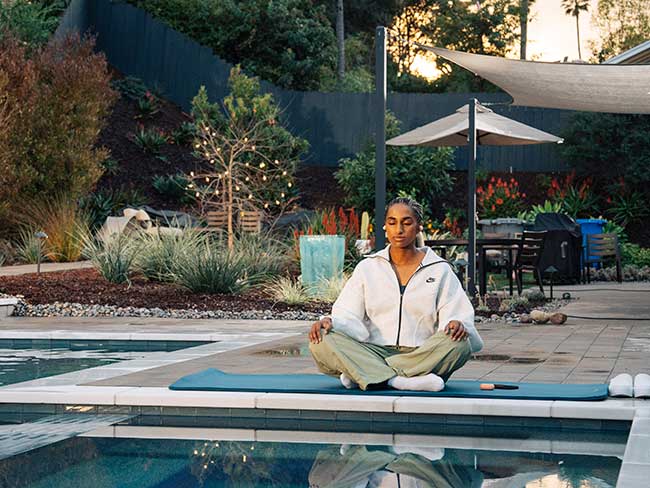

Learn how lifestyle medicine is part of cancer care at Kaiser Permanente.

July 27, 2023

Courageously facing hereditary breast cancer

Fay Gordon's breast cancer was caught in the early stages thanks to genetic …

July 26, 2023

Can you get chemotherapy while pregnant?

Chemotherapy can be an option during pregnancy. Find out how Kaiser Permanente …

July 21, 2023

Thankful for every day after HPV-related cancer diagnosis

Michael West shares his incredible journey from diagnosis to treatment …

July 14, 2023

Breast reconstruction surgery after cancer

A Kaiser Permanente plastic surgeon explains breast reconstruction options …

July 11, 2023

Cancer care for the body, mind, and spirit

Many people with cancer experience depression and anxiety. Mental health …

July 10, 2023

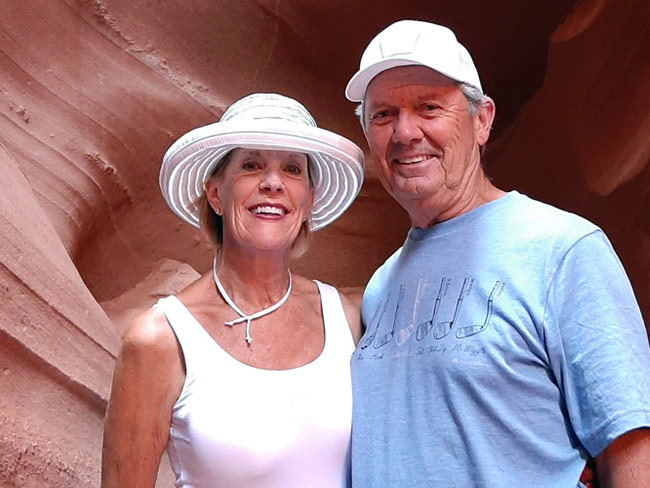

Beating colon cancer together: Miguel and Paula’s story

After they were both diagnosed with colon cancer, Miguel and Paula fought …

June 30, 2023

Men's mental well-being is a priority

Unique challenges and societal pressures can impact men’s emotional well-being …

June 30, 2023

Doctors' top tips to manage prostate cancer risk factors

Age, family history, and race are key factors.

June 30, 2023

Lung cancer survivor received ‘pioneering’ care

Doctor and mother of 3 Susan Brim received top-notch care after her lung …

June 28, 2023

Making waves to empower young girls

Kaiser Permanente and the San Diego Wave Fútbol Club host a second Wave …

June 27, 2023

Comforting, personalized care for a kiddo with cancer

Carter Shaver from Portland, Oregon, shares his optimistic smile after …

June 23, 2023

Get the mental health support you need

Kaiser Permanente is here to help with care and valuable tools to support …

June 22, 2023

Employee joined Connect study after bloodwork results

Help change the future of cancer prevention by joining Connect today.

June 22, 2023

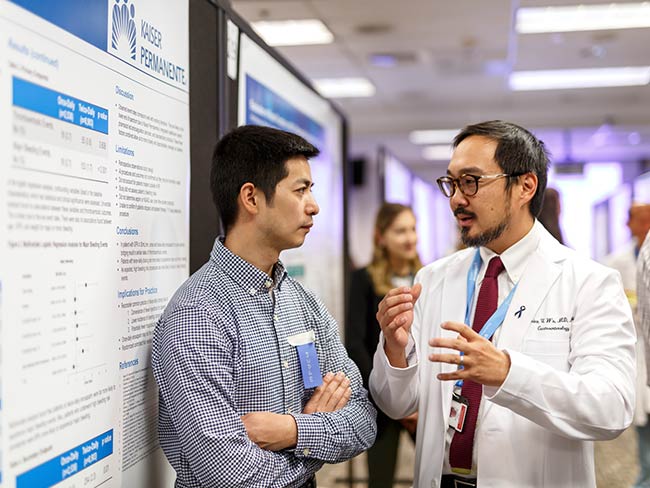

Higher survival rates for our patients with colon cancer

A new study compares Kaiser Permanente members in Southern California to …

June 21, 2023

And that’s why they call postpartum the blues

Take time to adjust to a new baby and lifestyle changes — and reach out …

June 15, 2023

Stay safe while having fun in the sun

Tips for preventing sunburn and decreasing the risk of skin cancer.

June 14, 2023

Living with stage 4 breast cancer

Thanks to personalized care from a team of skilled doctors, Christina McAmis …

June 9, 2023

Mental health, addiction, and the power of a peer

Shared experience helps young people in Oregon build confidence for their …

June 7, 2023

Teen social media use may lead to depression

Creating a healthy relationship with social media can help safeguard the …

June 5, 2023

Understanding and living with bipolar disorder

A Kaiser Permanente member shares his personal journey of navigating bipolar …

June 1, 2023

Policy recommendations from a mental health therapist in training

Changing my career and becoming a therapist revealed ways our country can …

May 30, 2023

The healing power of shared cancer experience

Peer mentoring program matches new cancer patients with others who’ve gone …

May 22, 2023

Sidelined by injury, a former nurse seeks depression care

Susan Sandhu struggled to find meaning in her life after an injury forced …

May 18, 2023

Addressing mental health trauma in a local community

Trauma-informed outreach efforts in Orange County are being recognized …

May 16, 2023

Managing trauma does not need to be traumatic

Expanded access to high-quality, affordable mental health care supports …

May 9, 2023

School shootings provoke anxiety in many children

Child psychiatrist defines anxiety, its symptoms, how to address it, and …

May 4, 2023

An unexpected cancer diagnosis

As a nonsmoker, Betty Schuldt’s stage 4 lung cancer diagnosis was surprising, …

April 25, 2023

Hannah Peters, MD, provides essential care to ‘Rosies’

When thousands of women industrial workers, often called “Rosies,” joined …

March 29, 2023

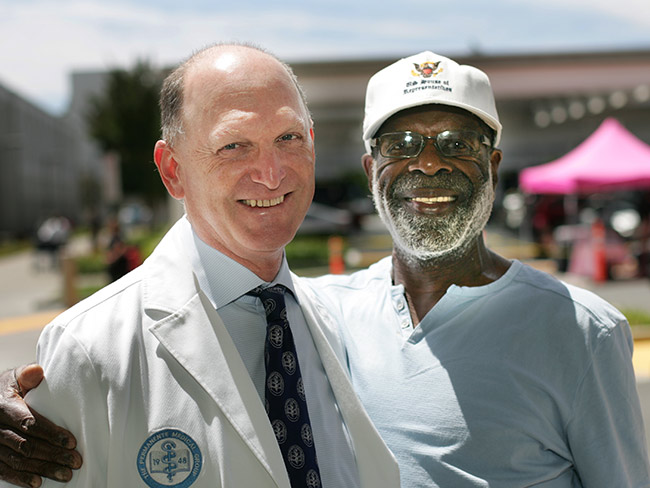

Volunteering helps create healthier communities

Kaiser Permanente’s partnership with Special Olympics Southern California …

March 24, 2023

Finding hope after a mental health and addiction crisis

Treatment for bipolar disorder and opiate addiction helps a Kaiser Permanente …

March 17, 2023

A call to 'Connect' for cancer research

A new study invites participants in Oregon to help uncover what causes …

March 16, 2023

Supporting our children after acts of mass violence

Southern California psychiatrist offers practical advice for parents to …

March 14, 2023

Colorectal cancer on the rise among younger adults

Learn why early screening is crucial for prevention and treatment.

March 13, 2023

Making waves with our first female sports ambassador

Kaiser Permanente in Southern California partners with San Diego Wave Fútbol …

March 7, 2023

For moments when you may not need to see a therapist

Kaiser Permanente provides members with convenient ways to improve their …

March 1, 2023

Spring forward: How to prepare for losing an hour of sleep

A sleep expert shares 4 practical tips for coping with the time shift and …

February 24, 2023

Nurturing expectant moms who have substance use disorders

Project Nurture in Portland, Oregon, provides treatment and a path forward …

February 23, 2023

Eating disorders on the rise among teens

Expert shares 5 valuable tips for parents and guardians to help children …

February 15, 2023

A new chapter for male patient with breast cancer

A multidisciplinary care team acted fast to help save the life of a Kaiser …